by James Stevens Curl

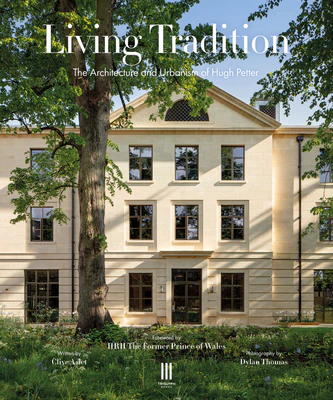

Hugh David Michael Petter (b.1966) is a Director at ADAM Architecture, and this handsome volume describes and illustrates some of his fine work. Like many of us who both value tradition, history and craftsmanship, and have studied and understood how materials are used in architecture, Petter found his “architectural education”, dominated by dogmatic Modernists, “quite hard”. Many humourless “tutors” with the shut minds associated with what is in reality a fundamentalist quasi-religious cult, held that any foray by a student into traditional or Classical architecture was morally wrong (though on whose authority such offences against “morality” were cooked up remains unclear) and therefore unacceptable.

When Petter produced a thesis design for his second degree, a new Library at Gray’s Inn, the Commissars for Compulsory Ugliness marked it down from a Distinction to a Borderline Fail at the final internal examination. Fortunately for Petter, the Head of the School at that time was the undogmatic Geoffrey Broadbent. He also received encouragement from the open-minded architectural historian Peter Hodson (1943–2021), who had been a pupil of that scourge of Modernism, the Cambridge Don David Watkin (1941–2018). The External Examiner then revised Petter’s Grade back up to a Distinction, an action that no doubt caused much gnashing of teeth in certain quarters. Petter recalls this as “quite amusing now, but it certainly wasn’t at the time”. I can imagine.

Modernists also dominated the selection panel for students wishing to pursue their studies at the British School in Rome, so Petter’s proposal to examine the development of Rome in the latter part of the 19th century when it became the capital of the newly united Kingdom of Italy was condemned with horror as morally questionable. A candidate with opinions more acceptable to the prejudices of the panel was granted a scholarship, but that person, before he could take up his award, accepted a position in London. Petter was then invited to become the Rome Scholar instead. This invitation coincided with an initiative by the former Prince of Wales, launched shortly after his Mansion House speech of 1987 in which he commented upon the appalling degradation of the built environment after 1945. With sensible advisors, it was proposed to establish a Summer School lasting a month and a half, partly in Oxford, partly in Rome, and one week at the Villa Lante. To its credit, his School of Architecture sponsored Petter to obtain a place on the Prince’s Summer School. From an environment where he was isolated in terms of interests and ideology, he found himself amongst 25 like-minded students who were passionately interested in traditional, especially Classical, architecture. Soon after the Summer School, he commenced his studies in Rome. There was no looking back after that.

He joined Robert Adam (b.1948) and others in Winchester, six years later becoming a Director of what was to become ADAM Architecture. His work has been varied and rewarding, including his appointment as Consultant Architect to the Duchy of Cornwall’s Estate at Kennington, London, where he has been involved in improvements at the grounds of the Surrey Cricket Club known as The Oval. Amongst these is a tidying up of the entrance, with new columns set off by very fine brickwork. The capitals feature ostrich-feathers, acknowledging the Duchy of Cornwall but also the Cricket Club badge. His master-plan for The Oval is even more ambitious; it includes surrounding the ground with 5-storey buildings described as a “Colosseum”.

Across the Pond, Petter designed the Millennium Gate, Atlanta, Georgia, which contains period room settings as part of a Georgian History Museum. The complex also houses offices and entertainment space for the begetter of the National Monuments Foundation, Rodney Mims Cook, Jr,, of Atlanta. This truly monumental complex was realised in the teeth of howls of protest from the Modernist architectural establishment, which absurdly regards any historical references as criminal. Two gigantic bronzes of Greek Goddesses of Peace and Justice, representing the civilising values that preside over a scheme of urban regeneration (which is what the Millennium Gate project actually is) were designed and modelled by the great Scots sculptor, Alexander Stoddart (b.1959 — Sculptor-in-Ordinary to HM the King in Scotland). They were cast in Basingstoke, Hampshire, before being shipped across the Atlantic. Peace is represented by Eirene, with her hand resting on the shoulder of the young Plutos symbolising Wealth. An Egyptianising Dike portrays the universality and antiquity of Justice, whilst standing before her is the boy Harpocrates.

At Oxford, Petter designed the Levine Building for Trinity College, a commission that originated through contacts made in Rome. The result is a very sober, stripped, Classical building, finely crafted in honey-coloured limestone.

Another work faced in limestone, this time a palatial house near Windsor, Berkshire, also contains splendid sculpture by Stoddart. The pediments of the handsome Corinthian porticoes feature River Deities personifying the Rhine, Indus, Hudson and Clyde.

The Duchy of Cornwall has begun the urban expansion of Newquay, Cornwall, with two developments, one at Tregunnel Hill commenced on site in 2012, and the larger Nansledan, which will not be completed for another thirty years or so. For these, Petter was the master-planner. The architecture draws on traditional materials, enabling construction to be carried out by local bricklayers, carpenters, roofers, plasterers, plumbers, etc., rather than relying on prefabricated components made in distant factories — something very important in a relatively deprived part of the country like Cornwall. At Tregunnel Hill, Petter’s ideas were realised in collaboration with Ben Pentreath and the Cornish architect Peter Hume. At Nansledan, several architects are involved.

At Woodstock, Oxfordshire, the Blenheim Estate instigated another urban extension called Park View, for which again Petter was appointed master-planner. The scheme also included cheaper housing to encourage younger people to settle there. The future centre of the development will feature commercial space on the ground floor and apartments above.

At the end of the book, there is a Catalogue Raisonné of Petter’s projects, with small colour photographs of some of them. To me, his most successful interventions are his tactful extensions to existing buildings and his skilful unpicking of insensitive botches. Amongst the latter is his careful rescue of Sir Edwin Lutyens’s 196a Piccadilly, London. It began life as a branch of the Midland Bank, but it fell victim to grossly ignorant corporate mistreatment as HSBC in the 1990s. Given its position beside Wren’s Church of St James, Piccadilly, it is enraging how HSBC got away with such vandalism.

With regard to other works on existing buildings, I reckon his restoration of the fire-damaged Old Rectory, West Woodhay, Berkshire, from 2011, is very good indeed, whilst his scholarly rescue of Chettle House, near Blandford Forum, Dorset, a fine work by Thomas Archer (c.1668–1743), is worthy of unreserved admiration, given the state it was in.

As with many who have chosen to work within the Classical and vernacular or traditional fields of architecture, Petter understands materials and their uses. His work encourages the next generations of master-craftsmen without whose essential collaborations no scheme could ever be realised. He also knows that the architectural framework within which fine craftsmanship can flourish needs constant renewal, involving careful teaching and instruction, so he is very much involved with the Art Workers’ Guild, the Georgian Group, the Building Crafts College, the British School at Rome and many other organisations.

This sumptuous book provides a record of his projects so far, including an extension to Lutyens’s British School at Rome. His use of the master’s Disappearing Pilaster (hated by Pevsner) is somewhat tentative, and it might have been more convincing if the base of the pilaster had appeared below the rustication at the entrance to the Sainsbury lecture-theatre. The collection is nonetheless impressive, evidence of what has already been an illustrious and extremely active career.

All photographs © Dyland Thomas, unless otherwise acknowledged.

2 Responses

By coincidence I visited a friend’s house over the weekend, and there on the coffee table was a photographic volume of the works of the execrable Frank Lloyd Wright.

I almost left immediately but while they were preparing a delicious dinner I thought I would flick through the pages and see if , maybe, I’d missed some of his “genius” and that heretofore unseen plates of his projects would convert me.

Let me tell ya, it was even worse than I thought , this man ought to have been removed from society for the horrors he inflicted on it. Every page I turned revealed another cringingly ‘orrible design .

So bad was it, that I started to resent my host for having it on display in his otherwise tastefully decorated apartment.

Me being me, I asked him how he could take the risk of letting let such public poison upset his guests but, surprise surprise, he leapt to his defence. (Mind you he does have German roots and he’s a computer programmer😊.) Bauhaus anyone?

It didn’t spoil the entire evening but I did warn him that I wouldn’t be entering that apartment in the future unless he could assure me that the art equivalent of radioactive decay was removed to a lead container in his storage area.

I’m really not entitled to an opinion as lofty as this, because I grew up on an ugly, crime ridden council estate close to the banks of the River Mersey.

Maybe that marvelously symmetrical Liverpool waterfront (now ruined by that same Bauhaus School viz; “The Catholic Cathedral”) gave me a sense of the beauty of classical architecture.

Gosh! Who would have thought such beauty was still being created?

Thank you for bringing this to wider attention.