A Distant Mirror: Looking back at ‘Not Without My Daughter’.

By Bruce Bawer

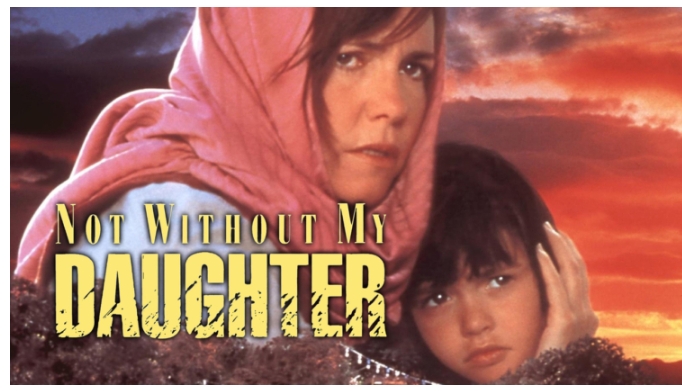

Perhaps you’ve seen the 1991 movie Not Without My Daughter. Directed by Brian Gilbert and based on the autobiographical 1987 book by Betty Mahmoody, it starred Sally Field as Betty, an American woman whose husband, Sayyed Bozorg “Moody” Mahmoody, an Iranian anesthesiologist (played in the film by Alfred Molina), took her and their four-year-old daughter, Mahtob, back to his homeland in 1984, in the middle of the Iran-Iraq War, for what was supposed to be a two-week summer vacation.

The vacation story, as it turned out, was a lie. Instead, at the end of the two weeks, Moody told Betty that he would be staying permanently in Tehran, and that she and Mahtob would be staying with him. When Betty protested, he beat both of them and kept Betty under lock and key. When she managed to sneak out and speak to the official at the Swiss Embassy who was in charge of U.S. affairs, she learned that nothing could be done for her: under Iranian law, the moment she married Moody she had lost her rights as an American and become an Iranian citizen – i.e., his property.

The vacation story, as it turned out, was a lie. Instead, at the end of the two weeks, Moody told Betty that he would be staying permanently in Tehran, and that she and Mahtob would be staying with him. When Betty protested, he beat both of them and kept Betty under lock and key. When she managed to sneak out and speak to the official at the Swiss Embassy who was in charge of U.S. affairs, she learned that nothing could be done for her: under Iranian law, the moment she married Moody she had lost her rights as an American and become an Iranian citizen – i.e., his property.

Realizing that it was useless to hope for help from abroad or to expect Moody to change his mind, Betty decided to play along, pretending she’d been tamed. When, after a few months, Moody finally bought her act, he began to grant her a small degree of personal freedom – which she savvily used to make connections that, after more than a year in Iran, enabled her and Mahtob to make a harrowing escape and return home.

I first saw Not Without My Daughter a long time ago. Betty Mahoody didn’t come back onto my radar until a few weeks ago, when a friend of mine visited from Israel and, upon departing, left me her battered paperback copy of Betty’s book. Reading it, I discovered quickly that the movie had actually toned down the primitiveness, the squalor, the casual savagery of the society Betty encountered in Tehran – a place where public toilets were veritable sewers, where the streets, packed with dead-eyed, grim-faced pedestrians, stank of garbage and body odor, and where Moody’s extended family – which was purportedly well-off and highly respected – was a gang of thuggish, superstitious morons who lived in utter filth, ate meals crawling with bugs, had conversations that consisted largely of repetitions of the words “Allahu akbar,” and spent most of the rest of their time in a “siestalike stupor.” Repeatedly, Moody beat Betty until she was limping and covered in bruises – a practice, she learned, that was par for the course in her neighbors’ homes.

In the movie, Moody doesn’t metamorphose from an ordinary American husband into a fanatical Islamic tyrant until his return to Iran; Betty’s book, however, makes it clear that he’d undergone this change five years earlier in response to the Khomeini revolution. While the movie depicts Betty as being surprised by Moody’s refusal to let her and Mahtob return to America, in reality she’d feared it all along. Why, then, did Betty agree to take Mahtob to Iran? It seems incomprehensible. But countless other Western women have made the same mistake.

The story of Betty and Mahtob, I recently discovered, didn’t end with Betty’s book. Thirty years later, Mahtob published her own book, My Name Is Mahtob (2017), about her childhood experience in Iran as well as her life afterwards in America. Mahtob is even more open than Betty is about their deep Christian faith – a fact that the movie’s script, by David W. Rintel, played down, even as it strove to include positive glimpses of Islam.

Mahtob provides fascinating details about her and Betty’s lives after their escape. For years, fearing that Moody would return to America and do them harm, they lived under assumed names. Betty’s book, and then the movie, brought fame and money but also international attention – and, among many Muslims in America, opprobrium. Betty bought a gun; she equipped their house with an alarm system and gave Mahtob “a panic button to wear as a necklace.”

Years later, while Mahtob was studying psychology at Michigan State University, she learned that a Finnish filmmaker was on campus, working on a “documentary” with her father, and that one of her fellow students was spying on her on their behalf. That film, Without My Daughter (2002) – which can be viewed on YouTube – is a staggeringly despicable sack of lies. Funded – disgracefully – by TV4 Sweden, Danmarks Radio, Arte (a European TV channel), and Finnish national TV station YLE, it has no purpose other than to is to discredit Betty’s story and to present Moody as a long-suffering victim of a mendacious wife who stole his child.

Far from being the bad guy, maintains Moody (who looks less like Alfred Molina than like the fatter, balder older brother of Dr. Now from My 500-Lb. Life), he treated Betty “like a queen” and deserves “A HUMANITARIAN RECOGNITION AWARD.” The film shows him wiping his tears, lighting a candle in a house of worship, praying at a grave. “My only sin,” he wails, “was that I loved my only child.” Moody claims he went to Iran to help his people in wartime and dismisses Betty’s book as a fiction concocted by her “Zionist” co-author, William Hoffer.

Moody even got Betty’s friend Alice – a fellow American who’d also married an Iranian and moved to Tehran – to parrot his line. Alice laughs at many of the assertions in Betty’s book. She insists that Betty “was free to go out at any time” and denies that Betty was beaten: “I never saw any bruises on her.” And she says she’s “come to believe that all along” Betty was planning to “make a lot of money” by making up tall tales.

Appallingly, the Iranian-Finnish director of Without My Daughter, Alexis Kouros, includes an interview with William Vincent, an MSU film studies lecturer, who glibly states that “Iran has been demonized” in the West and that Betty is one more example of the American habit of “turn[ing] your life into money.”

If Without My Daughter accomplishes anything, it’s this: it proves that Moody is indeed every inch the monster whom Betty wrote about in her book. Kouros, by putting Moody’s lies on screen, shows that he’s one more Muslim who lives in the West but despises it. And the Nordic state broadcasters, by funding Moody’s propaganda, provide yet another example of the eagerness of Western cultural elites to smear the West and whitewash Islam.

Betty Mahmoody is now 79 years old. Mahtob is 45. Moody died in 2009. Theirs is now an old story. But Betty’s book and the movie adaptation, both of which reached wide audiences, offered the West a vivid warning of what it means to live under sharia. If that warning – and others like it – had been heeded at the time, the mass Muslim immigration that has dramatically transformed Western European countries during the last few decades might never have been set in motion, and the natives of those countries might not be living now in societies that look increasingly like the one from which Betty Mahmoody fled.

To read Not Without My Daughter, or to see the movie, then, is to be haunted by a keen sense of lost opportunity – and to be intensely aware that Betty’s story will, before too long, be the story of everyone living in what was once a free and Christian West. The ultimate proof of how far we’ve already fallen is that the Western cultural establishment’s current ticklishness about Islam would make it utterly impossible for a major Hollywood studio to green-light a film like Not without My Daughter in the year 2025.

First published in Front Page Magazine