A Master of Clarity

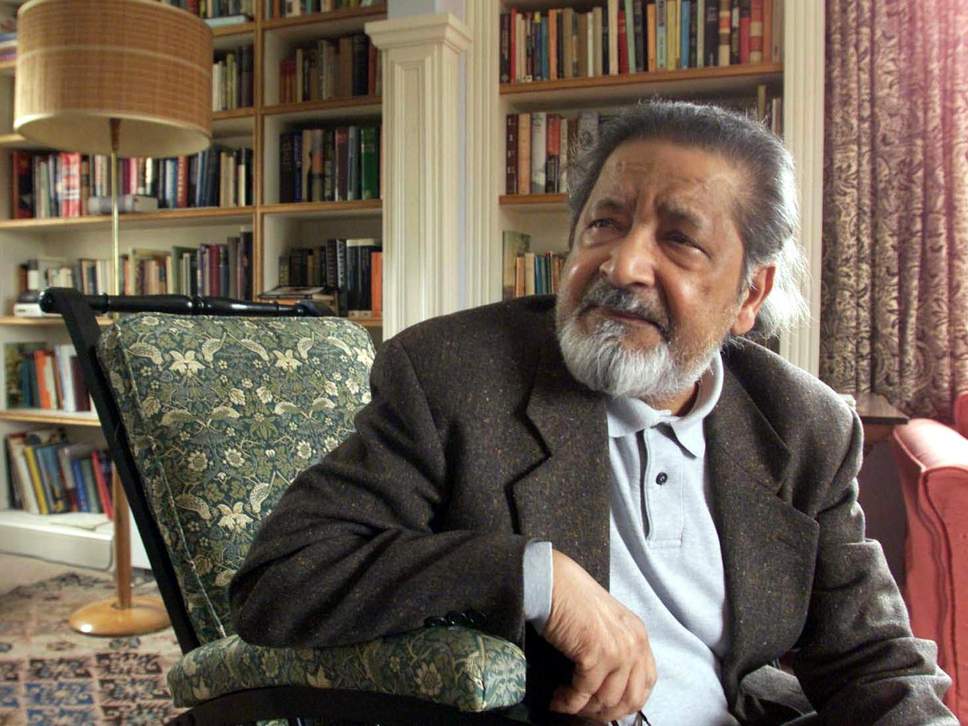

V.S. Naipaul, 1932–2018

by Theodore Dalrymple

V. S. Naipaul, who has died in his eighty-sixth year, was undoubtedly one of the greatest writers in English of the past 60 years. He wrote nothing that is not worth rereading or will not be read (assuming anything is still read) in another 60 years’ time. This is testimony to his utter probity as a writer, which he exhibited from the outset of his career when it might well have paid him, in his then-difficult circumstances, to lower his standards. He held it a duty, both to himself and the world, to produce only the best of which his prodigious gift as a writer, of which from the first he rightly had no doubt, was capable.

He was born in Trinidad in 1932, at first sight not a propitious place for a future novelist to be born. But the shallowness of his roots to a particular place helped him understand the sense of uprootedness that is so important a feature of life in the period in which he lived, and which is with us still. This permitted him to take the whole world as literary oyster, so to speak. A deracinated Hindu of a small British creole colony, educated at Oxford where he was not fully accepted as an equal, he was admirably placed to interpret the world that was coming into being, and he did it with an unfailing eye and great courage. He was always intellectually his own man and never accepted the simple ideological nostrums that took over the minds of so many intellectuals as a virus takes over the working of a computer.

In book after book, he exposed the reality of the new world without fear or favor, without genuflection to any piety, without attachment to any ideology or the use of any Procrustean bed of theory to distort what he saw and wrote, his virtue lying in seeing and describing what was there to be seen, once all the distorting lenses of ideological wishful thinking had been removed. His bedrock was human nature, and he was often derided—or even hated—for his clear-sightedness and his courageous determination to describe what he saw, from which no force on earth could have diverted or deterred him.

In an interview with the French newspaper, Libération, just before he received his Nobel Prize from the hands of the King of Sweden in 2001, he said, when asked whether a writer is condemned to be controversial:

Why must one always speak well of the world in which one lives, especially of the Third World? Would one require an American author always to speak well of America, or a German always to praise Germany? That would be stupid. Why should there be such a division in literature, and on the other side of the border the requirement that one should speak well of the world from which one comes? That would be condescension, contempt. People are full of prejudice, they don’t want to see what is there, and a good writer must always be disturbing.

There is no doubt that his reputation as a man suffered grievously from the revelations about his disgraceful, or worse than disgraceful, treatment of women that appeared in Patrick French’s book about him. This book was written and published with Naipaul’s full approval and permission; indeed, he provided much of the information himself about his own worst conduct, so that there appeared something almost exhibitionistic about the revelations. Many other people, of course, remember his kindness towards them.

Still, without in the least maintaining that a genius has less duty to behave properly than ordinary folk, it is by his writing that a writer, if he is remembered at all, will be remembered. And here V. S. Naipaul was preeminent among writers of English for practically all his adult life. He was a cure for simple minds.

First published in City Journal.