By Theodore Dalrymple

A French antiquarian bookseller from whom I buy books from time to time sends them to me through the post with old-fashioned postage stamps on the packet. How pleased I am when I receive such a packet! Postage stamps are almost relics of the past, and I have long reached the age when relics of the past are more precious to me than hopes for the future. I derive almost as much pleasure from the stamps as from the books; and almost as much pleasure also as from receiving a handwritten letter, a rare occurrence indeed.

I regret the passing of the postage stamp, for stamps, like banknotes, were often objects of beauty. Like most boys of my time and age, I had a period of collecting them, though I was never a serious philatelist, excited by watermarks and perforations.

I still remember, however, the independence of Ghana (in 1957) as an important event in my tiny life: For Ghana, formerly the Gold Coast, broke with colonial philatelic tradition and replaced the restrained, skillfully engraved depictions of local life in sober colors—a different color for each denomination—with bold but crude and brightly multicolored designs. At first I thought this some kind of liberation, but it soon dawned on me that the liberation, if such it was, was one of bad taste. Interestingly, that liberation from restraint was soon to affect the postage stamps of my own country, which became brighter and cruder in design: a difference akin to that between the tender drawings of Winnie-the-Pooh by E.H. Shepard and the crude cartoons of Disney.

One of the reasons that I regret the passing of the postage stamp is that children (especially boys, for the urge to collect seems more a male than a female trait) no longer go through a stamp-collecting phase. I speak, of course, in generalities: The population of the world is large, and there is no human conduct impossible to find in it. And if you ask what boys did before there were postage stamps to collect, that is to say before 1840 when they were invented, I would reply that the era of the postage stamp coincided with that of the prolongation of childhood, when leisure in childhood became widespread, if not universal.

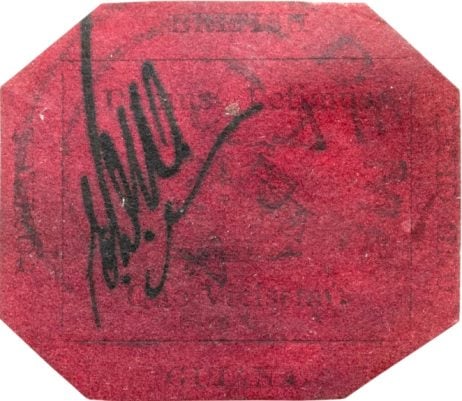

It didn’t take long for postage stamps to become objects of collection, and now they are objects of investment as well (which is to say, speculation). The world’s most expensive stamp, the British Guiana magenta, of which only one example is known to have survived, was last sold for more than $8 million in 2014. Issued in 1856, it was already recognized as a quite exceptional rarity in 1873 and therefore of more than usual value. Moreover, philatelists, like bibliophiles, are ever on the lookout for small misprints or other errors that can turn something worth a dollar or two into more than most people accumulate in a lifetime.

This teaches a not-insignificant lesson: that the labor theory of value must be wrong. According to this theory, taken up by Marx but not originated by him, the exchange value of an object depends on the amount of socially necessary labor to produce it; but this theory cannot account for the fact that one tiny piece of paper should be worth next to nothing, while another, very similar piece of paper, that took no more labor to produce, is worth a fortune and whose exchange value is enough to buy an entire house. I do not say that this is rational, I say only that it is so; an intelligent Martian descending to Earth would no doubt find it further evidence of the folly of mankind. The labor theory of value can be saved only by means of dishonest mental acrobatics, for example by claiming that British Guiana had to be established for the magenta stamp to be produced and that its establishment was immensely expensive in labor.

taken up by Marx but not originated by him, the exchange value of an object depends on the amount of socially necessary labor to produce it; but this theory cannot account for the fact that one tiny piece of paper should be worth next to nothing, while another, very similar piece of paper, that took no more labor to produce, is worth a fortune and whose exchange value is enough to buy an entire house. I do not say that this is rational, I say only that it is so; an intelligent Martian descending to Earth would no doubt find it further evidence of the folly of mankind. The labor theory of value can be saved only by means of dishonest mental acrobatics, for example by claiming that British Guiana had to be established for the magenta stamp to be produced and that its establishment was immensely expensive in labor.

None of this, of course, concerned me as a young stamp collector, though there was undoubtedly a competitive element to the hobby—it was a joy to possess stamps that none of one’s friends possessed. But there was a kind of wisdom or providence in the hobby, for it painlessly taught those who pursued it many things that they might otherwise have been refractory to learning, such being the stubbornness of boys. (I have never subscribed to the view that boys, or at any rate most of them, naturally seek knowledge.)

Stamps taught me a lot about history and geography, though not perhaps in any depth. Just how much they taught me became evident to me more than forty years later. The hospital in which I was working suddenly appointed a bureaucrat whose job it was to badger the staff about diversity, equity, and inclusion; and it so happened that our city had also suddenly seen an influx of Congolese illegal immigrants posing as asylum seekers.

Knowing the Congo as I did, I sympathized with the illegal immigrants individually, but sympathy with an individual is not quite the same as approval of a policy. Be that as it may, the DEI bureaucrat sent all the staff of my hospital a circular informing them that the main language of the Congo was Arabic.

Ah, if only she had collected stamps in her youth! By the age of 10 I would have been able to tell her that this was not so, that French was the lingua franca of the country, and I would have regarded her circular with contempt. But that she did not know anything about the subject of her circular taught me another lesson: that the purpose of a DEI bureaucracy is not to improve anyone’s life, apart from that of the bureaucrats themselves, but to employ people who have spent too long in useless education, a most dangerous class if left unemployed and dissatisfied.

What a terrible misfortune has been the decline of stamp collecting except for speculative purposes! An alliance of stamp collecting and the internet could have been such a powerful instrument of education of the young. For example, one of the stamps recently arrived from my bookseller was a beautifully engraved portrait of Marshal Juin, a man of equivocal record in the history of France. Into how much modern history could a child easily have entered if he had collected such a stamp (an aesthetic education in itself by comparison with the aesthetic coarseness of so much modern entertainment) and followed the links that aroused curiosity would have suggested.

First published in Taki’s Magazine

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link