Art Under — And Out From Under — Islam (Part III)

by Hugh Fitzgerald

As discussed in Art Under And Out From Under Islam (Part I), MoMA has been eager to score political points against Trump’s ban by rather confusedly claiming that Western artists have learned so much from the “colonized” (and by implication, Islamic) peoples, and that the creations of Muslim artists put on display somehow prove how wrongheaded is that temporary ban on visas for Muslims from seven countries (only 12% of the world’s Muslims, held up for only 90 days). There is no logical link, of course, but what does mere logic matter when we are protesting a “racist executive order”? Exactly how those artists have been harmed is unclear. None of them have not been prevented from continuing to make art, or to show it anywhere they want; none of those whose works are being shown have apparently been affected by the ban. Nonetheless, the display of some works by Muslim painters was proudly described in ArtNews as a “riposte” to Trump’s “racist executive order.”

I suggested that art museums in the Western world, if they wished to treat of “Art and Islam,” might do better to use their resources for exhibits devoted to the greatest destruction of art in world history, that which has been conducted by Muslims, over 1400 years, vandalizing or destroying many different works of art and architecture – frescoes, mosaics, paintings, statues, synagogues, churches, Hindu and Buddhist temples — wherever Muslims conquered. For this would alert people in the West to one more possible consequence of Muslim demographic conquest that they have not considered.

And there is another issue, involving “Art Under – And Out From Under — Islam,” to which a second exhibit could be devoted. This would be about not the destruction of existing art and artifacts by Muslims, but rather, about the limits placed by Islam on artistic creation by Muslims themselves because of the hadith – to be found in both of the most reliable (Sahih) collections of Al-Bukhari and Muslim, in which Allah’s Messenger reports that “angels have declared that they will not enter a house in which there is a dog or a picture” — that has led to a ban, in Islam, on depictions of living creatures. That means no portraits, and no paintings which include depictions of humans (or animals), even if they are only secondary to the main subject matter. Landscapes are acceptable, as long as there is no human figure, however small, in the painting; so, obviously, is abstract art. There have been artists willing to break this ban, especially in secular, rather than religious art. But the ban itself still stands, and has had its chilling effect on Muslim artists, whose highest expression has been in mosque architecture and Qur’anic calligraphy. For 1400 years, Muslims have been prevented by their own faith from enjoying the freedom of artistic expression that non-Muslims take for granted. If true solidarity with Muslims is to be offered, instead of MoMA posturing about “racism,” it should offer an exhibit that shows what those artists have lost by the limitations their faith imposed on what was admissible to create.

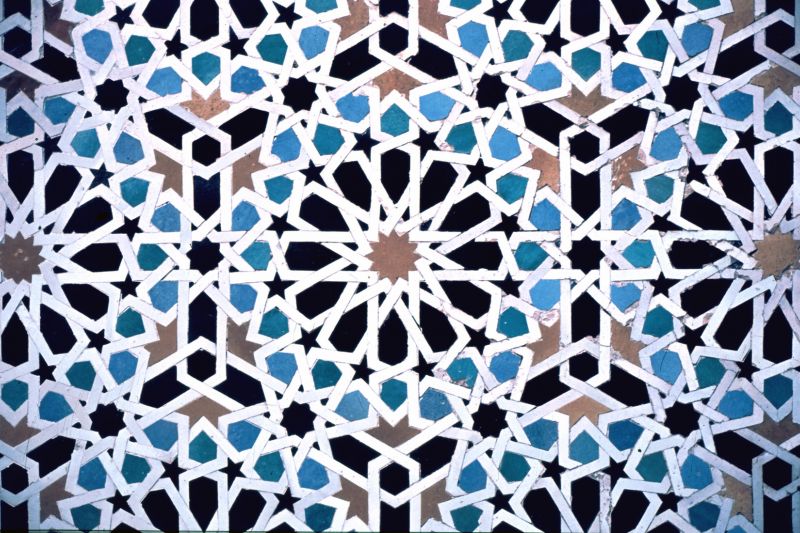

Let a few galleries be given over to this exhibit of “Art Under – And Out From Under — Islam.” One might be called the “Islamic Portrait Gallery,” and on its walls would be telling rows of frames, all of them empty. A second gallery would have paintings by Western artists: some portraits, landscapes that contained figures large and small, others that were purely landscapes, while still others would be examples of abstract art, Kandinsky or Mondrian, of such color-field painters as Frank Stella. And finally, photographs of the geometric patterning inside the walls of mosques, possibly hung side by side with photographs of the frescoes, mosaics, paintings, and statuary to be found in churches, of subjects sacred and profane, by way of telling contrast. Visitors to the exhibit could be given cards on which the works displayed would be listed, and might be asked to check, next to each work named, whether it would be, for Muslims, Halal or Haram. That should reinforce their understanding of what that hadith has meant for Muslim artists and Islamic art. Muslim artists should welcome this sign of solidarity, not deplore it. Their real plight – not the 90-day ban on entry to the U.S., but the 1400-year ban on their freedom to depict human beings – is a subject fit for treatment by a major museum.

The two exhibits devoted to “Art Under – And Out From Under — Islam” could also be put on simultaneously. The first would heighten awareness of how Muslims have through history treated the art and artifacts of non-Muslims, right up to the Islamic State’s recent rape of Palmyra. The second would heighten awareness of how Islam has constrained artistic expression, and implicitly suggest, with its examples from Western art, the kinds of things Muslim artists might have created but, halted by a hadith, never had the chance.

Is it conceivable that MoMA would ever put on such shows? Not under present management. Those running the museum seem more exercised about a 90-day ban on immigration for 12% of the world’s Muslims than about the future of either Western or of Islamic art. After all, why should an art museum trouble itself about art, when there’s all that “racism” and “Islamophobia” to complain about? But let us allow ourselves to believe that eventually some enlightened curators and connoisseurs, and some deep-pocketed donors too, will become truly “subversive” – that word favored by art dealers and museum curators alike, as they flog their wares — and decide that museums have a responsibility to show what Islam has meant both for non-Muslim art over the centuries, and for the creative possibilities available to Muslim artists. Such an exhibit would truly “educate and challenge” visitors – as ArtNews complacently claimed MoMA’s exhibit of Muslim artists does. “Art — Under And Out From Under — Islam,” will be strong medicine, true, but given the museum world’s chronic illness, it may turn out to be just what the doctor ordered.

First published in Jihad Watch.