by Guido Mina di Sospiro (December 2022)

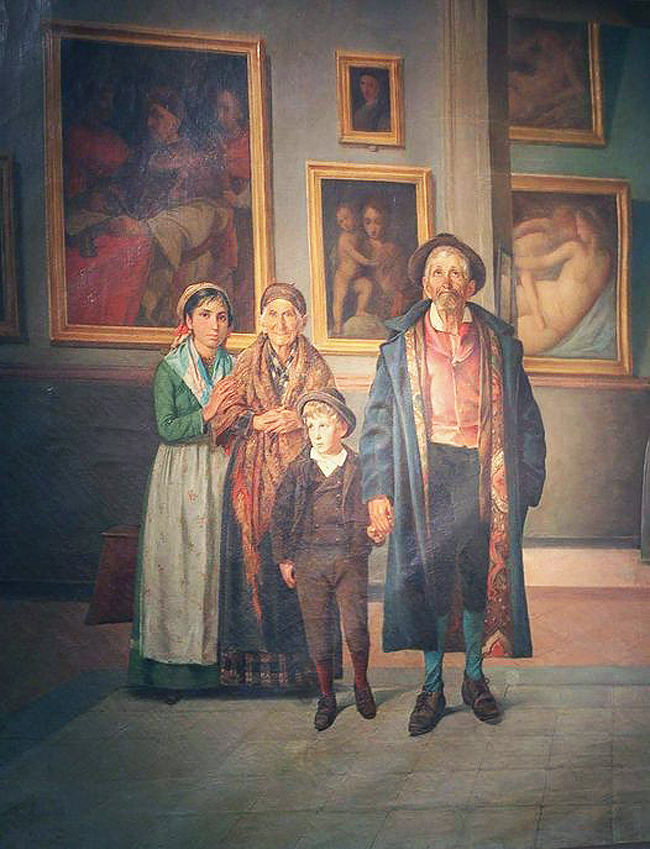

Scuole diverse (Different Schools), Antonio Augusto Moriani, 1890

Before returning to the US a few weeks ago, I visited the Museo di Capodimonte, in Naples, Italy, and took a picture of this painting—by Antonio Augusto Moriani, as it transpired, dated 1890. It represents four hillbillies inside a museum, completely out of place. The phrase La Vérité en peinture (The Truth in painting) came to mind, the title of a book by Jacques Derrida, which he himself took from Cézanne. I was also reminded of Roman Jakobson six functions of language, of which the one in the painting would be the sixth: the metalingual one, and that is, the use of language (Jakobson calls it “code”) to describe … itself. Indeed, here is a painter using a museum with many paintings in it to make a point.

The portrayed hillbillies still exist, though they are no longer peasants, but tourists, millions of them, wearing sneakers and shorts and wielding that quintessential implement of the 21st century: the smartphone. Opportunities for selfies abound and seem to be the main activity such visitors are preoccupied by. And, contemplation? Conferring with the muses? Not so much.

Again I must mention linguistics. In French, Italian and Spanish there are two very similar yet distinct words, respectively: langue and langage; lingua and linguaggio; lengua and lenguaje. Such two words correspond to the English word “language”; langue, lingua and lengua: chiefly used to refer to individual languages, such as French and English; and langage, linguaggio and lenguaje, which primarily refer to language as a general phenomenon, or to a language applied to another field, such as music, the fine arts, and many more. Therefore, it is easier for the French, Italian and Spaniard to understand that there is a language to be learned that deals with painting, another one with music, architecture, and so on.

Let us now imagine that my favorite Japanese author comes to town, to present his latest work. I don’t miss my chance and go listen to him as he is also, I have read, an eloquent and compelling speaker. At the end of the soirée, I am dumbfounded. He did speak, and at length, but in Japanese for the whole time, and with no interpreter present. All his words, no matter how interesting and vibrant, were lost on me.

That is what happens to the millions of casual (major) museum visitors who patiently wait in line for hours for their turn at the Louvre or at the Uffizi: everything they then see is lost on them because they don’t know the language of painting. And in fact, just by observing them, one can discern everything but appreciation, let alone awe or emotion. So, why do they bother? Why do they crowd all major museums, but only the major ones? “Minor” museums, in fact, are consistently deserted just about everywhere (and a delight to visit); if they were really keen on the arts, they would visit them all.

It is as if the unknowing masses were mandated to do something they could not possibly understand. Remember the analogy with the Japanese author.

In one of my very rare posts on Facebook (since deleted), commenting on Antonio Augusto Moriani’s painting I wrote:

“‘We don’t speak the language!’ When visiting museums nowadays, one comes across the same category: tourists wearing shorts and taking selfies are the contemporary hillbillies. The question is: why do they go to museums at all?”

Wouldn’t you know it? I unleashed the paladins of flatulent egalitarianism (rank nonsense in the instance of knowledge) and the enforcers of inclusiveness. The smartphone-wielding casual museum-visitors have all the rights to be there, with their attendant short attention span pathology and garrulous triviality.

I do not question their right to be there, unless their aim is to throw tomato sauce on a painting or two, but wonder at how much fun it can be to parade in front of dozens and dozens of paintings without speaking their language.

I should further clarify this concept, since, as noted, the English language does not have the right word for it: if I say, “In the Emperor Concerto Beethoven resorts to enharmonic modulations” those two last words are completely lost on the layman. And even if he were to read what “modulation” means in musicological terminology, he still could not understand the concept, as it would refer him to “tonality,” with its complex system of chord progressions. Only somebody who plays an instrument capable of producing chords and is familiar with tonality can understand the concept of modulation, which is quite central in the development of western music.

What rubbed the paladins of flatulent egalitarianism and the enforcers of inclusiveness the wrong way, though they would not know it, is the concept of initiation, which is a fundamental concept in traditionalism, but we live in very anti-traditional times. The so-called expert is in fact an initiate. By din of studying and learning about different periods and contexts in the history of art, the Biblical and Greco-Roman mythology that so often inspired the old masters, different schools, different individual painters and differing techniques, and of course visiting as many museums and galleries as possible, the art enthusiast gradually acquires the language of art. The more she deepens her studies, the more fluent she becomes; eventually, she will be an initiate. But that can only happen over a long period of time.

I have visited the Uffizi in each decade of my life, starting in my teens. Each time it has been a richer experience, though the paintings have remained largely the same. That is because each time I went back, I was a little more fluent in that language, which is not to say I have acquired perfect fluency in it yet.

A book I recently read comes to mind, L’occhio dell’artista. Una lettura oftalmologica della storia dell’arte (The Eye of the Artist. An Ophtalmofgical Reading of the History of Art). The author, Cesare Fiore, an ophthalmologist, goes through the history of western art by examining and reconstructing the eyes and vision defects of some of its great masters. It is a book that took him decades to research and write, and could not be more intriguing. In it, two languages converge: that of ophthalmology and that of art. It would have been wonderful to go to a museum in the company of Dr. Fiore, but sadly he recently passed away.

Since we live in the tutorial age, one in which anything can be found on YouTube, including the most refined lessons in music, art, architecture and just about every other field of human endeavor, countless languages can be learned by anyone, from the comfort of their home, and for free. All such languages have never been so at everybody’s reach. And yet, what we get are the smartphone-wielding masses preoccupied with their next Instagram post—of themselves, rarely of the masterpieces in front of which they stand.

In my YouTube wanderings I have come across an admirable classical guitarist from Sweden—one Lucas Bar—who has had the following to say:

“I had a bit of talent and artistic inclinations as a kid, but 90% of mastering something is becoming obsessed with the joy of learning, realizing you will never master it anyway. There is no reaching the end point. So just enjoy the journey.” Lin Yutang could not have put it better.

Table of Contents

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, and Forbidden Fruits.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

19 Responses

The conclusion of this piece is a quote by a Swedish guitarist to “just enjoy the journey,” yet the author spends the entirety of this article slamming the great unwashed and, to his view, ignorant masses who annoy him in art museums with their selfies and lack of fashion sense and supposed ignorance about the language of art – for doing just that, enjoying the journey. One does not visit art museums to not enjoy art. Even neophytes merit the opportunity to at least attempt to enjoy art if they have no knowledge or training in it, that is they are ignorant of art’s “linguaggio”. It is always fascinating to observe self-appointed “experts” lecturing lesser mortals in the correct method of viewing art, the proper manner of listening to music, the correct shape of the mouth when drinking a wine, or the right posture to take in reading a book. The author’s generalizations and assumptions about the people that he says that he sees in art museums around the world is nothing more than negative generalizations/stereotyping. This sentence is particularly egregious: “And yet, what we get are the smartphone-wielding masses preoccupied with their next Instagram post—of themselves, rarely of the masterpieces in front of which they stand.” The author assumes to know the motives of those he sees in art museums as nothing more than self-absorbed social media addicts rather than people who are just enjoying the journey, as recommended by the Swedish guitar player. I rarely see such people in art museums as they are described by the author. I suspect that they do not exist, and are to be found only in this author’s thoughts when somebody has the temerity to step in his line of vision and block his view of a famous Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Cy Twombly, Blinky Palermo, or Andy Warhol.

There goes the inevitable but highly entertaining display of flatulent egalitarianism. The Swedish classical guitarist has been practicing eight hours a day since his early teens. Does enjoying the journey imply masochism?

Lack of humility is the problem. People don’t bother with learning the language, but somewhat magically they will enjoy it anyway. Sure, listening to the Japanese author speaking in Japanese was most enjoyable. My dear reader: have you recently been to the Louvre, Prado, Uffizi, Vatican Museums, and so on and on? The throngs are there; it’s a selfie festival, all-year-long. Incidentally, I don’t care for any of the painters you mention at the end. If you had even marginally understood what I wrote, you would have known it.

Guido: I am convinced Gene Delly Croy was using a lot of words to cleverly call you blowhard or a snob. I don’t know for certain, but that’s what I’d put my money on. Your response to him didn’t prove him wrong.

An interesting picture, and an interesting discussion. A couple of thoughts: to my eye, this is a middle-class family (they are very decently dressed) that came for some entertainment (which, in 1890, would have been limited to book reading, live theater or musical concert, or a visit to an art gallery — did I miss anything?) The old man’s face expresses skepticism — he is apparently not too convinced that the work he looks at is well-made; the boy is attentive, but — appropriately for his age — has no opinion; the women, young and old, are plainly posing to the painter, and nothing else — I guess they just came along, to keep company. Perhaps Daumier’s prints of art shows that teem with rushing visitors are best evidence that looking at art — just to be able to say “I’ve seen it” — was a major pastime for his favored subject, a Paris bourgeois. This said — you focused on a wonderful painting, and thanks for sharing it. How to read it though, is a different question. What we read into a work differs for each of us — and who’s to say whose reading is correct?

But that is precisely what is expected from people who lack humility. Why bother to learn a language? Though I suppose that’s a lost cause with Americans! The Talibans of egalitarianism and inclusion feel threatened in their hard-won mediocrity or, often, utter ignorance. All the piece is saying is, study, learn, enjoy the process, then museums will be a joy that at present you simply cannot envision.

The painting is entitled “Scuole diverse” (Different Schools). I could find very little on Antonio Augusto Moriani, but his painting did stick out from the hundreds on display. Many others, of course, are remarkable, but I knew their authors. This one came as a surprise. Incidentally, the Museo di Capodimonte, housed in a Bourbon royal palace, IS a major museum, but not quite as crowded as others since, apparently, the masses haven’t been mandated to visit it yet, so still enjoyable. Conversely, access the Cappella Sansevero, which used to be a curiosity for just a few connoisseurs, is now impossible without standing in line for hours. That said, Antonio Corradini’s “Pudicizia” (1752) and Giuseppe Sanmartino’s “Veiled Christ” (1753) are of the most technically prodigious sculptures in the world, bar none.

“Why Do the Masses Crowd the Major (But Only the Major) Art Museums of the World?”

Maybe, that’s where the art is?

The painting works as an illustration of untutored bemusement in front of the old masters, but it’s not a good painting in itself — the figure group looks stuck on, like a collage. I think Moriani has not mastered the linguaggio of his art.

In my experience, the majority of tourists do not take selfies. Instead, they photograph every painting in the room, one after another, moving left to right. Often, the painting is not looked at directly, but only through the lens of the smartphone. I speculate that these photographs will seldom, if ever, be looked at again. Why then do they do this?

Susan Sontag (and I agree with her) thought that tourist photography was a form of displaced labour. The tourist, away from the strictures of the 9-5 routine, feels uncomfortable both with the enforced leisure of the holiday and the strangeness of the surroundings. To assuage his anxiety, he takes photographs. The taking of the photographs is the point of the exercise, not the resulting image.

You can’t blame it all on the tourists, however. The museums market themselves as “destinations” on “bucket lists” that have to be visited and checked off so the tourist can honestly say they’ve “done” a particular city.

My solution would be to limit free entry to any national museum to nationals of that country (I hope this is not too flatulently egalitarian). This would concentrate the mind wonderfully. Do I really want to pay £10/15/20 to see all those old pictures? An added benefit would be that the money gained from those who do want to would mean that the mega-exhibitions (usually of French Impressionism) that take space away from the permanent collection wouldn’t need to be staged so regularly.

One thing that puzzled me in Mr Mina de Sospiro’s piece:

“Only somebody who plays an instrument capable of producing chords and is familiar with tonality can understand the concept of modulation, which is quite central in the development of western music.”

Is he suggesting that you have to be a practising musician to understand music? Or, by extension, to be a practising painter to understand the techniques of underpainting, glazing and impasto in e.g. the paintings of Titian?

Well, it does help to understand that the arbitrary twelve tones per octave of the well tempered clavier, which are employed in the vast majority of western music since Vivaldi and Bach, make it so that a C sharp is the same as a D flat, but the tonality of C sharp major or minor is not the same as the tonality of D flat major or minor. That is the concept behind an enharmonic modulation, with the latter being a sudden change in tonality, which in Beethoven’s times was not quite contemplated, hence his resorting to that stratagem. Schubert changed things… In my experience people have trouble understanding that a G7th resolves on a C major–which is as elementary as it gets. Explaining to them what the Diabolus in musica (devil in music), or the tritone, or the triad and the flatted fifth is, is virtually impossible, and yet it’s very simple.

It’s as if my piece has stirred into action the anti-learning brigade. But, learning is not a dishonor. Curiosity is a gift from the gods.

In the Capodimonte Museum there was a patient and competent teacher who was guiding a class of about twenty kids from elementary school, stopping here and there and explaining to them what they were seeing, as it certainly helps to know a bit of Biblical and Greco-Roman mythology in order to appreciate many if not all of the old masters. He was doing a good job, succeeding in piquing the kids’ curiosity. It was clear that they were enjoying themselves.

Learning is a miracle we are all capable off. It takes a modicum of humility and work, though, but it is ultimately very rewarding. I’m sure you agree.

“But, learning is not a dishonor. Curiosity is a gift from the gods.”

and

“Learning is a miracle we are all capable off. It takes a modicum of humility and work, though, but it is ultimately very rewarding. ”

I unreservedly agree with both sentiments!

https://www.newenglishreview.org/articles/how-the-most-musical-century-in-the-history-of-western-civilization-came-about/

Good for you Guido for writing such a provocative article. I don’t hold an opinion on the matter because the museums and galleries I visit advertise and promote their exhibitions to the demographic you highlight in your WTF point. What starts out as a divine gift from the sidereal gods ends up scrutinized as a marketing campaign to see how many asses pass through the museum’s turnstiles regardless of whether they are of the initiate or the profane.

Guido,

You’re obviously correct in all of this. Gene, the first commenter, is clearly low-end. People who visit museums should be qualified to do so. That is, museums like the Louvre or the MET should have gatekeepers who confirm every visitor as qualified to view the art. Art shouldn’t be wasted on the plebeians and the careerist working-class whose only purpose in visiting the museum is a good selfie and a check mark on their bucket list. Art should be appreciated only by those who are truly capable of appreciating it. Those who don’t appreciate it and have no capacity to understand it should be barred from admission and—if they complain—arrested and confined for disturbing the sacred space of the repository of the world’s great human achievements. Personally speaking, once i had to wait four hours to see the exquisite Gioconda, Monna Lisa at the Louvre. Tragically, no docent appeared to move those people along (all of them clearly self-involved and ignorant), so that people better than them (e.g., you and me, and David) could view the masterwork. I complained to Louvre management and they said they would see to it. All of this is so obvious it hurts.

Excellent essay. I completely agree with the author regarding this issue. In fact, I’d go a step further and demand some sort of bona fides prior to permitting entry to even view well-known masterpieces. Want to see Michaelangelo’s David? Picasso’s Guernica? Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or Last Supper? Each potential viewer would need to prove he (or she) has visited the museum or gallery at least twice prior before being permitted to view the masterpiece he wants to be able to say he’s seen. This would eliminate much of the riff raff. They can all stand in line to view that horrendous Antonio Augusto Moriani painting above, but #getawayfromMonet !

I read recently that many of the museums that normally charge admission now give free admission for people who are on welfare/state benefits. Atrocious policy that needs to stop asap and doing so might go a long way to eradicate this very important problem.

#getawayfromMonet

Most people do not share a love of scholarship, but they can admire other attributes of the visual experience, plus the notion of a glance into the minds of all those people who once lived and walked around in the town outside.

Unfortunately, that is not so. For the unknowing, the profane, the non-speaker of the language, fine arts museums are a solemn bore. Such visitors have no references, they don’t understand what they are seeing, the contexts, the styles–nothing. In six words: they do not speak the language.

The person who does not speak the language of art and nevertheless goes to a fine arts museum cannot have any other reaction than that of a child: utter boredom. I have witnessed what I am stating innumerable times. Or the ignoramus asking, in the MET, and repeatedly, “Are these copies?”, that being her only reaction.

I am taken aback by many of the responses my piece has occasioned. What is wrong in learning something? I do not mean scholarship, but the basics of the history of art? Instant gratification will not be had in a fine arts museum; in order to enjoy it one must speak the language, and there is no way around it. The more fluent (s)he becomes, the more fully (s)he will enjoy her time in the museum.

We live in the Tutorial Age, one in which everything can be learned, and for free, by watching the appropriate videos on YouTube; yet at the same it’s the Age of Entitlement, one in which the arrogance of ignorance reigns supreme; no wonder people are severely allergic to humility, which is the point of departure for any sort of learning. O saeclum insapiens et infacetum!

Guido, it’s you who is misunderstanding the criticism. Nobody here has defended ignorance and deciding to not “learning something.” That is not the argument. I actually agree with the fact (not opinion) that there’s a whole population that cannot appreciate the art we so much admire. I’ve seen it, too; it’s a fact that I believe isn’t debatable. However, should they be denied the opportunity to go? Obviously not. Is there a chance one painting may whet an appetite for more? Small chance, but possible.

A lot of these people don’t know what they don’t know. They lack so many skills and basics in humanities, they don’t even know there is an accessible place to start.

I definitely agree with your argument, but you made the argument in such a horribly tone deaf way, you invited much of the criticism. You clearly have a privileged life. But you come off as a total elitist who lacks any understanding of the fact that most people don’t get to travel the world 12 months a year and don’t come from one of the oldest and wealthiest families in the world. We love culture and art, but we choose museums to visit that have the best collections because we only have a few weeks per year to travel.

It sounds bad when you, who gets to travel to any museum in the world, study and master any subject at leisure, and live such a fortunate life, criticize “the masses” for their lack of cultural context and knowledge of art. You have no idea why the “masses” are lacking in these matters. Not everyone is as lucky as you to be so highly intelligent and wealthy. Your piece has a condescension to it that is very unpalatable. You may not have intended your piece to sound this way.

Teona, You are assuming things about me that are incorrect, but anyway: nowhere do I question the right the masses have to go to a major fine arts museums. I merely wonder why they do so, as it is a solemn bore for them. For example in Rome, I would encourage casual visitors not to stand in line for hours for the Vatican Museums, but just walk around the historical center, maybe going for a drink at an hotel’s roof terrace, taking in the amazing view. Easier on their feet, and far more rewarding. I cannot understand the obligation they obviously feel to visit major museums, since they derive no pleasure from them. Contrary to what you suggest, I do think about their hard-earned money and the little time they have–why not make the most of it by really enjoying themselves? Lastly, palatable or not, I don’t care: truth is, alas, undiplomatic. In fact, it should be refreshing to read it, for once, no matter how (arguably) abrasive.

You may be familiar with the mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna. I visited it over 40 years ago. They had a system where you put a few lira in a box and the lights would go on, otherwise the place was in darkness. Nobody would pay to light it up. All they did was use flash photography, and a startled, restrained cry would issue from the people as the art of the place was glimpsed for a second before retreating into the gloom again. It’s box ticking isn’t it? Art galleries are free in England (art for all!), but maybe if people were made to pay they might just try and get their money’s worth.