Adventures May be Stimulating But They Aren’t Fun. Unconvinced? Ask Sir Richard Burton. Or me.

by Reg Green (September 2020)

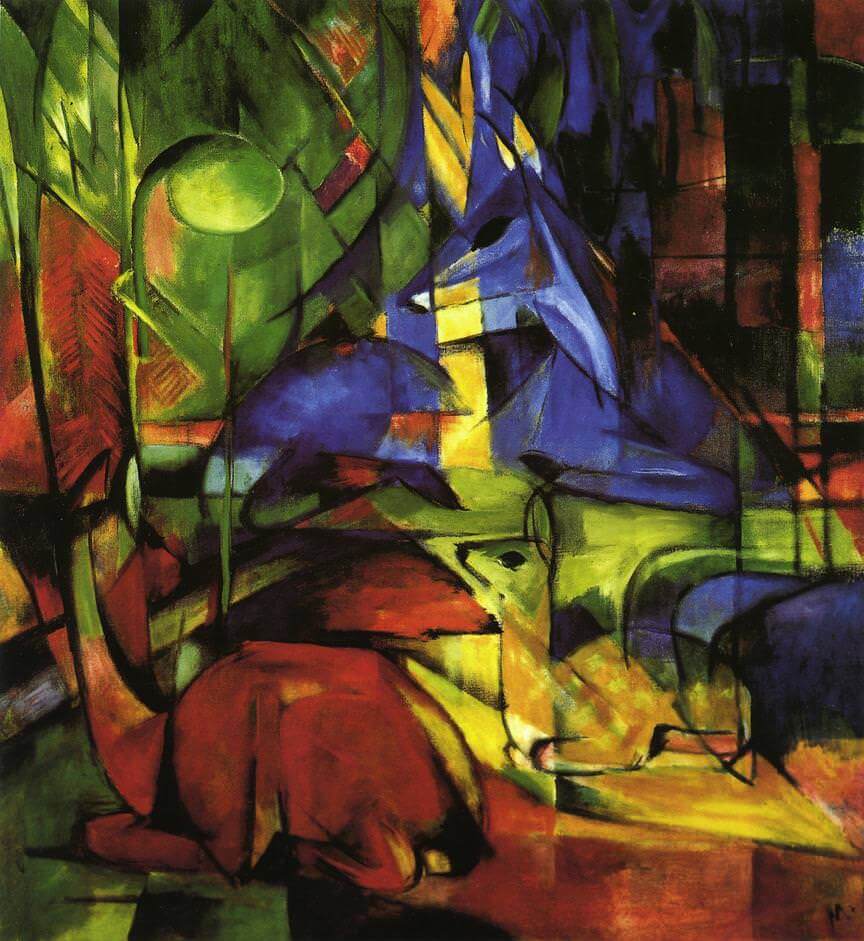

Deer in the Forest, Franz Marc, 1914

A famous explorer (I think it was Sir Richard Burton, the 19th century Englishman who amazed the world with his death-defying exploits in Africa and the Middle East—what else can you call dressing up as a dervish and joining a pilgrimage to the forbidden city of Mecca?) said an adventure worthy of the name could be enjoyed beforehand or afterward but not during. I’ve always believed it. Time and again, I’ve eagerly looked forward to a risky or testing event, turning it over and over, studying maps, looking up book—and, when it’s ended, relishing memories of fighting off the bitter cold or the baking heat.

But what I thought of while it was happening was quite different: the gloves I’d left at home or the sunblock I’d forgotten to put on or whether I’d get to where I was going before dark. I had an example this week—a minute version of what Sir Richard had in mind but real enough for me. It happened on a broad fire road in the local mountains that I’ve walked up a dozen times.

One morning, about seven, on the way back I was about to walk past a half-hidden deer trail that climbed steeply off the road but which I’d seen a buck climb up when I surprised him a week or two ago. “Why not?” I thought and began to scramble up the loose earth, slipping and sliding, but slowly moving up by seizing the tough bushes that after a few yards almost enclosed the trail. The climate around here, in the mountains north of Los Angeles is tough and so is the vegetation and soon both hands had cuts on them and my clothes had a rash of thorns sticking to them, shaped like arrowheads, going in easily but difficult and painful to pull out.

All around was dense vegetation, impossible to force a way through except for this little path. Slowly and with a lot of backsliding, I forced my way up, till I reached a ridge from which I had a glorious 360-degree view. I walked along it for maybe a 100 yards till it ended in a cliff of bare rock, dropping more steeply than the angle of repose. That’s true of a lot of slopes in the San Gabriel mountains: they are so steep that rocks find it hard to hold on. I drank it all in, loving the sense of freedom. If you’d asked me at that moment, I’d have said Burton was wrong. ‘During’ was bliss.

After a few minutes I’d had my fill and turned back looking for the tiny path I’d come up. It wasn’t there! I retraced my steps, looking carefully at every place where the bare earth showed under the trees until I found myself back at the cliff. I’d missed it again. I turned around and walked back more slowly this time and with a faint trace of uneasiness. I’ve written glibly many times about these mountains being impenetrable because of the dense undergrowth. Now ‘impenetrable’ had a sinister, rather than a cavalier, sound to it.

So it was with relief that I spotted the telltale signs of trampled-down vegetation and all was well again. I followed these signs down the steep slope until—without warning—they ended abruptly in a small clearing completely enclosed by vegetation, impenetrable vegetation you might say, except for the way I’d come in. I turned round and hauled myself back to the ridge, more wearily now. Perhaps I hadn’t walked back far enough on the ridge, I thought, and with the cliff at my back I walked what seemed like a long way. But then, just as I remembered it, there was the beaten down grass I was looking for where some animal had slept.

Foolish of me to have given up too soon, i thought. I must be more anxious than I knew. I moved down clinging to the thorny bushes but easier of mind until—oh no!—the path ended as suddenly as the other one had in a circle of that all too familiar wall of small but tenacious bushes. By now I couldn’t fight down a sense of real unease. I was in a place where no one would think of looking for me and cell phones don’t work here. By the time I’d scrambled back up to the ridge I was also getting tired. For the third time I set off toward the cliff, examining every place where some loose rocks might suggest a way down. I tried one or two places tentatively, but all quickly petered out and then one that went down a little longer than the others but like them became surrounded by that same imprisoning tangle of branches.

I was about to go up yet again when my heart leapt: wasn’t that a slightly worn patch under that overhanging network of leaves? I made my way across the loose scree toward it with a fast-beating heart and—yes!—when I pushed the canopy aside a trail of small stones continued. I followed them—not exactly praying but wishing awfully hard—and Glory Be to the Good Fairy—I saw the road 50 ft. below.

The way was now even closer to the vertical so I went down on my back, holding the bushes tightly first with my right hand, then the left. This was much more difficult than the trail I’d come up but at least the way was clear. I slithered down the last few feet and oh joy! there I was on the broad, beautifully-graded, vegetation-free, anxiety-free dirt road with my car only 15 minutes away.

In my mind, I checked Burton’s three stages and found he was right only once: yes, the ‘during’ was the exhilaration surrounded by apprehensiveness that he had in mind. But as, at the beginning, I’d turned off the road on to the deer path impulsively, I’d had only the most fleeting thrill of anticipation. And even the ‘after’ had lost a lot of its fizz after picking dozens of spiteful thorns out of my shirt and boots and contemplating the grass stains and scuffed pants.

It hasn’t escaped my notice that there is more than a trace of absurdity in linking the difficulties of a man who crossed the Empty Quarter of the Arabian desert with those I had within sight of the InterContinental hotel in Los Angeles, I am comforted, however, that this literary device has an honored place in the history of memoirs.

I often think of a fellow university student in England who spent weeks of his summer vacation on a fishing trawler in, as he always called them thereafter, ‘Icelandic waters.’ In the 1940s that was—again, what else can you call it? —awesome.

When he came back, he wrote a story for BBC Radio, who immediately replied saying they loved his adventurous tale. Unfortunately, they couldn’t use it, they added, because it was rather more exciting than Scott’s similar expedition to the South Pole.

.jpeg)

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Reg Green is an economics journalist who was born in England and worked for the Daily Telegraph, The Guardian and The Times of London. In his spare time he wrote about jazz for the Telegraph, sharing the paper’s coverage with Philip Larkin, wrote a column on soccer and reviewed books on European history. He emigrated to the US in 1970 and in time started an investment newsletter.

His life changed course in 1994 when his seven-year old son, Nicholas, was shot in an attempted robbery while on a family vacation in Italy. He and his wife, Maggie, donated Nicholas’ organs and corneas to seven Italians, a decison that stimulated organ donation around the world and is known as “the Nicholas Effect.” Reg wrote a book, also called The Nicholas Effect, which was the basis of the television movie, “Nicholas’ Gift,” starring Alan Bates and Jamie Lee Curtis.

He has five other children varying in age from 24 to 59. At 91, he continues to work full-time to bring attention to the hundreds of thousands of lives that have been lost because of the shortage of donated organs and, when not traveling, hikes every day in the Southern California mountains. His most recent book is 90 and Not Dead Yet.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast