91 and Not Dead Yet

Words Matter

by Reg Green (January 2021)

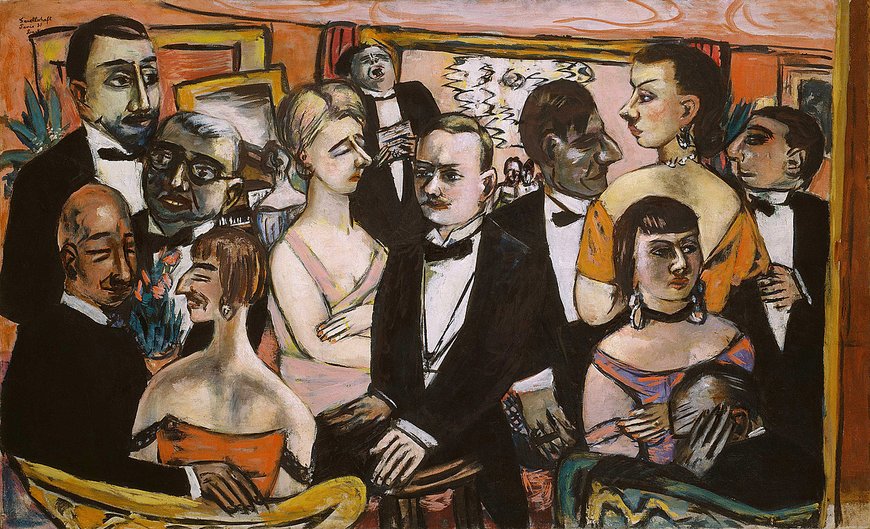

Paris Society, Max Beckmann, 1931

As our children are halfway through the school year and, as this year the struggle to learn is harder than ever, I’m reminded that when I was a child, we had an almost irresistible stimulus to literacy outside the classroom: an unending flow of the most sophisticated popular songs of all time. In those days (would you believe?) striving to be as literate as possible was considered commendable. Hence the appeal of:

You’re the top, you’re the Colosseum

You’re the top, you’re Louvre Museum

This was Cole Porter, whose many interior rhymes gave the high-flying words an extra kick.

You’re the Nile, you’re the tower of Pisa

You’re the smile on the Mona Lisa

The challenge of “You’re the Top” is that every comparison has to be not with the good or even the excellent but with the absolute best—Napoleon brandy with Mahatma Ghandi, an O’Neill drama with Whistler’s mama, the National Gallery with Garbo’s salary (or, to modernize it, how about Zuckerberg’s salary?)

Now that I’m old, bitter and twisted, the lyrics I hear nowadays seem to me to be childiish and repetitive, though no doubt there are plenty of exceptions.

There was only one Cole Porter, of course, and I’m ready to admit that, though many of the lyrics in those far-off days were banal, we still ate them up.

Still, he was not just a one-off.

We had Lorenz Hart, simultaneously mocking and tender:

Is your figure less than Greek?

Is your mouth a little weak?

When you open it to speak

Are you smart?

And Johnny Mercer, alone with a bartender at quarter to three in the morning:

We’re drinking, my friend,

To the end

Of a brief episode.

So make it one for my baby

And one more for the road.

Whatever you were doing, instantly you’re there with the two of them.

Even the seeming homeliness of an Irving Berlin song was really a sensitive balancing of down-to-earth elements that he had somehow brought together into a whole that was different from any of its parts, a butterfly out of crawly caterpillar.

Think of the lonely GI in Europe in the final winter of World War II, whose mother and sister had sent what they thought he’d need most but had missed the mark:

You can keep your knittin’ and your pearlin’,

If I’m a gonna go to Berlin,

Give me a girl in my arms tonight.

What compression. Shakespeare, for whom brevity was the soul of wit, would surely have approved. Mind you, they had no choice: record disks in those days could hold just over three minutes. However splendid your triumph or earth-shattering your loss, if you couldn’t tell it in that time you couldn’t tell it at all.

But in the right hands it could be done and was done, time after time. What, for example, can better sum up the sense of an utterly failed teenage love life, while romantic attachments are blossoming all around, than this sparse verse from 1940?

Sailors have sweethearts on the wharfs

And even Snow White had seven dwarfs

But I ain’t got nobody

And nobody’s got me.

It was seemingly done effortlessly and certainly we absorbed effortlessly. The dullest kid in the class transmogrified in his thoughts into a debonair troubador. The key word there is ‘seemingly.’ We have it from Ira Gershwin’s sister that while tunes poured out of George, Ira would wrestle all night to get one line to sound effortless. “Doesn’t that show George was a genius and Ira just talented?” she was asked. No, I don’t think that at all, she replied. “Words are much harder to get right than tunes.” Bless her.

So out of that struggle we get verses like

The Rockies may crumble

Gibraltar may tumble

They’re only made of clay

But our love is here to stay.

Notice too that so many of these lyrics were both subtle and funny. We could certainly use more of both those manifestatios of culture nowadays.

The golden age of lyrics had one late flowering and it was a glorious one. The Beatles poured out lines that were as powerful, poignant, witty, succinct, melodious, ironical…you can exhaust the thesaurus . . . as any that had come before.

Where else can you find the life of an aging spinster summed up with such devastating clarity?

Eleanor Rigby was buried along with her name,

Nobody came.

Who else in youth culture would have had enough interest to try?

Luckily, mankind’s astonishing resilience, though nowadays it finds words not worth the effort, has poured its genius into technology that not only makes music universally accessible but preserves it intact for (almost) ever.

So maybe a thousand years from now in the doctor’s office of some grim prison, whose goal is to wipe out every last memory of accumulated centuries of decadence, some prisoner, more independent-minded than the rest, will be murmuring under his breath:

You’re a craze, you’re Marilyn’s dimple,

You’re a phrase by Doc. Dalrymple

Ok, I’ll work on it.

Notice for Readers: But now I have some sad news for you. I’ve been writing this “91 And Not Dead Yet” column for the last few months but now something has happened outside my control and I regret to say this will be my last article in the series. I have enjoyed it a lot and I hope you have.

There is one consolation. Beginning next month, I will be starting a new column called “92 And Not Dead Yet.” Hope you’ll be here.

__________________________________

Reg Green is an economics journalist who was born in England and worked for the Daily Telegraph, The Guardian and The Times of London. In his spare time he wrote about jazz for the Telegraph, sharing the paper’s coverage with Philip Larkin, wrote a column on soccer and reviewed books on European history. He emigrated to the US in 1970 and in time started an investment newsletter.

His life changed course in 1994 when his seven-year old son, Nicholas, was shot in an attempted robbery while on a family vacation in Italy. He and his wife, Maggie, donated Nicholas’ organs and corneas to seven Italians, a decison that stimulated organ donation around the world and is known as “the Nicholas Effect.” Reg wrote a book, also called The Nicholas Effect, which was the basis of the television movie, “Nicholas’ Gift,” starring Alan Bates and Jamie Lee Curtis.

He has five other children varying in age from 24 to 59. At 91, he continues to work full-time to bring attention to the hundreds of thousands of lives that have been lost because of the shortage of donated organs and, when not traveling, hikes every day in the Southern California mountains. His most recent book is 90 and Not Dead Yet.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast