A Big Little Book on C.S. Lewis

By Daniel Mallock (April 2019)

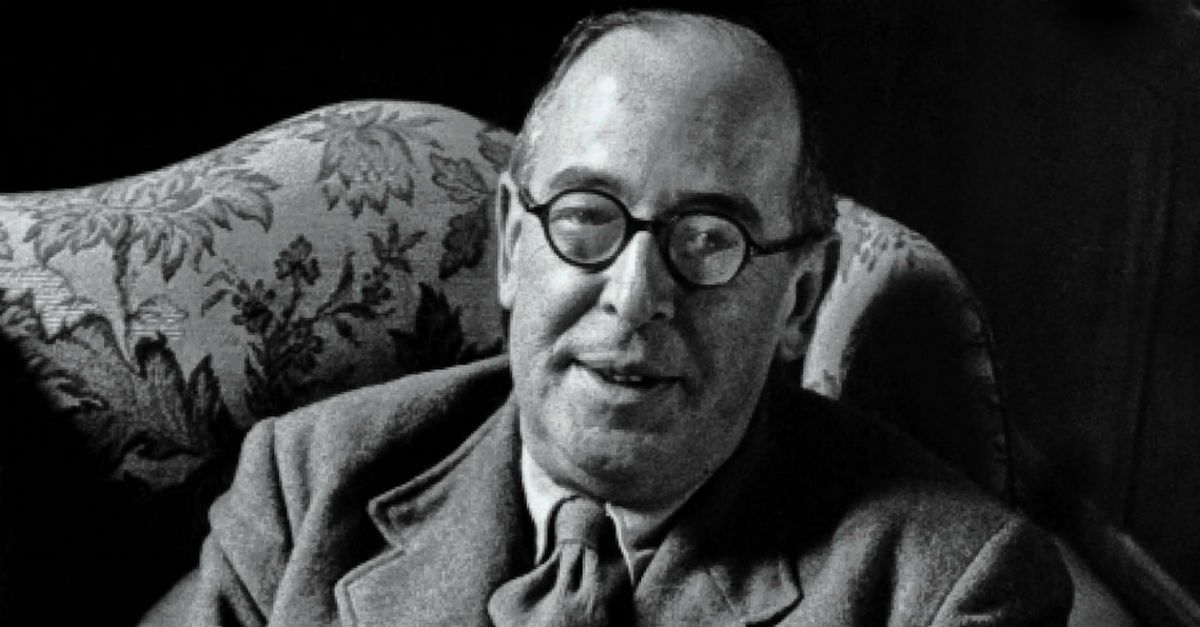

C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis: A Very Short Introduction

By James Como

It is a rare thing when the demands of function are met and fulfilled in a thing’s form. The proper unity of form and function is so unusual that such things and events, little and big, always draw entirely merited attention. Such is the case here.

James Como, a student and expert of Lewis, retired professor, noted scholar, author, and Contributing Editor at NER, has written a very short, but very meaningful introduction to the massiveness that is C. S. Lewis. It is not merely a successful big book in a tiny little package, it is a superb study and homage to one of the great literary and scholarly geniuses of the last century. Widely known and revered by many, Lewis was an Oxford professor and author of many books including The Chronicles of Narnia (7 vols, 1950-56), scholarly works, essays, letters, broadcasts and perhaps for many, some of the most important works of Christian apologetics in the last several hundred years. The Screwtape Letters (1942), and Mere Christianity (1952) are masterworks of the apologetics genre.

C.S. Lewis had long been a non-believer. The tragic death from cancer of his mother firmly formed him into someone who could not accept that a loving God could allow such things—therefore there can’t be a loving God, or any God. Lewis’s pursuit of joy in living finally took him to what he found to be the font of true joy, the acceptance of Jesus Christ as the Messiah and everything around what that acceptance meant. This extraordinary shift brought him many new fans and even a new wife, an American ex-pat, perhaps ironically, named “Joy”. Upon her untimely death, also from cancer, Lewis wrote a memoir of his grief under a pseudonym, A Grief Observed. Some readers, wanting to help Lewis, sent him the book as a comfort unaware that he had written it.

In much the same way that Tolkien will be known throughout time for The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, so long as people enjoy stories, heroes, villains, and the endless battle between good and evil, and the pursuit of real knowledge and understanding, Lewis has done the same. That Tolkien and Lewis were great friends and colleagues at Oxford, who reviewed and critiqued one another’s work, should come as no surprise. “Was Lewis essentially a fugitive, from culture, from the spirit of his age, perhaps from time itself?” Como asks. “I believe he was.”

Read more in New English Review:

• Waiting for Corbin

• Letter from Berlin

• Memory Gaps

James Como thoroughly knows his subject. One of the founding members of the New York C. S. Lewis Society, Dr. Como, in his youth, had been deeply touched by reading Lewis. Como experienced what many Lewis fans have across the years. “. . . Coming through the words there was a distinctive, concrete person who exuded trustworthiness.” The words of Lewis’s friends support this admiring view, and show that sometimes a writer truly does put some of him/herself there on their pages.

“Fifty years ago members of the New York C.S. Lewis Society identified some sources of his appeal, intangible characteristics of style or voice, which seem as much a part of the man as any doctrine,” Como writes. “Brilliance, clarity, Britishness, nobility, humility, veracity, and joy were the words used by the membership. Those who met Lewis personally have remarked on these same qualities. As Thomas Howard (scholar and critic) put it, he was ‘down to the last molecule the man I would have expected.’”

Lewis, for all his humility and brilliance, was no stranger to controversy, as anyone with strong views and beliefs can’t help but be. Consider this from Mere Christianity (originally delivered as part of a BBC broadcast).

A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic—on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg—or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to . . . Now it seems to me obvious that He was neither a lunatic nor a fiend: and consequently, however strange or terrifying or unlikely it may seem, I have to accept the view that He was and is God.

Dr. Como observes that “the severity of both logic and tone are striking.”

The edit/revision that Jefferson sent to his friend, Dr. Rush, for safe-keeping involved the removal of all references of the divinity of Jesus and the retention of all the moral lessons of Jesus-the-great-moral-teacher. This is in direct contrast to Lewis’s formulation. For Jefferson (a non-Christian Deist), the morality of Jesus was paramount. In an 1809 letter to a friend, Jefferson wrote, “We all agree in the obligation of the moral precepts of Jesus, and nowhere will they be found delivered in greater purity than in His discourses.”

Read more in New English Review:

• Slightly Subversive or Just Odd Books on my Nightstand

• Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time: First Movement

• O Words, Where Are Thy Sting?

Lewis’s absolutism of what he saw as divine truth, a great source of solace to him, was a surety that fueled other insights, not as limited (for the reader) by religious orthodoxy or rigidity. In his June 8, 1941 lecture at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford, Lewis gently warned his audience about the dangers of fetishizing this world and ignoring things non-corporeal and more elevated.

When a champion and appreciator of a person writes about that author, artist, leader, etc., (i.e., the subject), there is a danger of slipping into hagiography. Dr. Como is fully aware of these dangers and deftly avoids them. Throughout the book critics and detractors of Lewis have their say, too, so that a fair and comprehensive perspective is presented. Additionally, elements of Lewis’s private life are included that both add complexity to the whole portrait and provide the reader with a well-balanced approach.

This is a small book, you can fit it in your back pocket or your purse, or comfortably in your backpack. It’s a small book with a big impact because James Como has done a magnificent thing—he has brought a massive body of work, a man of extraordinary intellect, talent, accomplishment, and output into sharp focus. He’s done this with style, with affection, with fairness and scholarship—and a great depth of knowledge and skill that is clear from the first page to the last.

C.S. Lewis: A Very Short Introduction is a small book—and it is a big success. Big and good things sometimes come in small packages. Much like the wardrobe in The Chronicles of Narnia, opening an ordinary thing can be an unexpected entrée to an entirely new and fantastic world.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Daniel Mallock is a historian of the Founding generation and of the Civil War and is the author of The New York Times Bestseller, Agony and Eloquence: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and a World of Revolution. He is a Contributing Editor at New English Review.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast