by Janet Tassel (October 2011)

Blessed and Beautiful: Picturing the Saints

by Robert Kiely

Yale University Press, 344 pp.

“Who in this audience is really content with life and has never had a fly fall into his macaroni?”

Thus would the comical 14th-century Saint Bernardino of Siena launch into one of his famously zany sermons. “You…over there…sleeping….I come here to bring you the word of God and you settle yourselves down to sleep so that I have to interrupt my sermon to wake you!”

Saint Bernardino of Siena by Jacopo Bellini

The feisty Bernardino, patron saint of boxers, is one of the Christian saints chosen by Robert Kiely, professor emeritus of English at Harvard, for Blessed and Beautiful, his elegant and sensuous study of some of the world’s most wondrous art (Italian Renaissance and Medieval) and the twelve saints depicted therein. Thirteen, actually, if we count the 3rd-century Saint Lawrence in a chapter Kiely devotes to critic John Ruskin. Ruskin takes us to Fra Angelico’s San Marco Altarpiece for a weirdly ecstatic gaze, not at Saint Lawrence the martyr, but at the gorgeous pearls on Lawrence’s tunic.

This book, as much a pleasure to hold as to peruse, does not try for inclusivity. Rather, it is a connoisseur’s choice, a baker’s dozen including Mary, mother of Jesus; John the Baptist, Mary Magdalene, Mark, Sebastian, Rocco, Augustine, Benedict, Francis, Catherine of Siena, and Louis of Toulouse. Each saint is sumptuously illustrated, but not necessarily in accordance with tradition; Kiely often subordinates the iconography and enumeration of attributes that readers of this genre enjoy—the “who’s carrying what” game we play in books and galleries.

Rather, Kiely tells their stories at a slant, through literature–prose and poetry both ancient and modern. “For me,” he writes, “the paintings were the catalysts for rereading biblical, hagiographic, and theological texts…Like all literary criticism, they contributed to, interfered with, changed, and complicated the way I read.”

And through the body, the word made flesh:

Saints obviously had bodies, tall and short, large and small, male and female. Even when they mistreated them, or when they were mistreated by others, those bodies usually appeared extraordinarily attractive in Italian Renaissance painting. Representations of two of the most gruesome martyrdoms – Saint Lawrence roasted on a grill and Saint Sebastian shot full of arrows — tend to play down the pain and play up the grace of the nearly nude male body.

Which leads to the fact that

it is impossible to overlook the masochistic and sadistic [and homoerotic] elements in the aesthetic culture of Christian martyrdom, but to stop there can too quickly close down consideration of other possibilities and explanations for the behavior of saints. There is more to sainthood, its physical and aesthetic expression, than the perverse pleasure of the suffering body.

These are living and suffering and often crazy individuals, a far cry indeed from Ambrose Bierce’s definition of a saint as “a dead sinner revised and edited.”

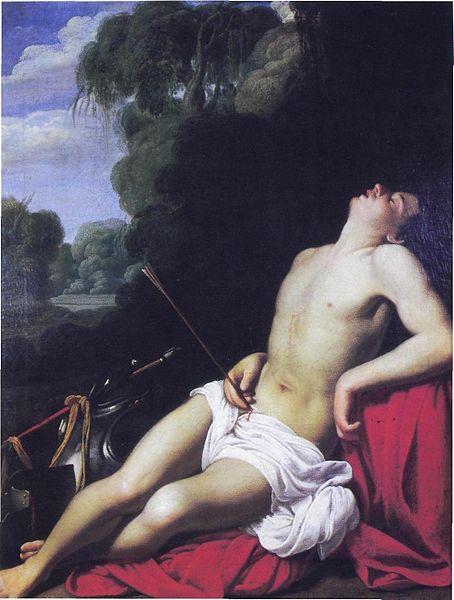

Take, for example the 3rd-century Sebastian, “nude, supple, sexy” Sebastian, “patron saint of gay men,” as Kiely reminds us. Kiely yokes Sebastian together with Mark the Evangelist and Rocco, the 14th-century plague victim, in a chapter devoted to the concepts of manliness and strength—the hero as “hunk” (Kiely’s word). Sebastian’s martyrdom–punishment for destroying pagan idols and openly praying to Jesus—was to be shot so full of arrows “that he looked like a porcupine.” Using paintings by Perugino and others, however, Kiely finds a “perfectly relaxed, beautiful Sebastian,” and in Titian’s Sebastian a “homoerotic fantasy” of Promethean manliness.

Saint Sabastian by Carlo Saraceni

This kind of exegesis would not have been appreciated by the aforementioned crank, Bernardino of Siena. For Bernardino, sodomites have “strayed from the womb”; “there is no sin on earth that so seizes the soul.” Bernardino, portrayed by artists including Bellini, Gozzoli, and Vecchietta, is “old, skinny, and bald; his tight, thin mouth suggests that he has lost both his patience and his teeth.” Wearing a Franciscan habit, he carries a sign with a blazing sun bearing the initials HIS, in Greek for the first three letters of Jesus’ name.

An itinerant friar, he travels all over Italy and into Europe, preaching his tub-thumping sermons to huge and noisy crowds. “Oh, oh,” he cries, “Friar Bernardino is coming! One says well of it and one says evil….Of every one who says good, one hundred say evil!” Comparing “backbiters” to frogs, he croaks, “qua, qua, qua.” As Kiely says, “The crowds, his loose tongue, and his enormous success in promoting himself”– he is also the patron saint of advertising and public relations — naturally stirred up some uneasiness in Rome. He was hauled before the Inquisition twice, and twice acquitted. “As with most celebrities, controversy only increased the interest of the people.”

One of Kiely’s virtuoso turns is the chapter in which he compares and contrasts bony Bernardino, the “angry prophet,” with “the youthful, mild, smooth-faced Louis of Toulouse,” born a century earlier. Though they are often depicted together in paintings like the gorgeous Crivelli Madonna Enthroned with Saints, no two saints could be more dissimilar. And yet they are joined by several threads: Both have chosen the harsh Franciscan way, devoted to poverty and humility; thus both wear the humble Franciscan garb. Louis’s simple gown, however, is frequently hidden beneath his richly embroidered bishop’s robes. He also wears the bishop’s mitre and carries the crozier—reluctantly, it would appear. His doleful countenance and the mitre at least a size too big, and the tentative, indolent way he holds the crozier confirm his sadness. For though he was idolized by the crowds attracted to him by his youth and beauty and fame, he wanted none of it; he craved only “solitude, scholarship, and service.”

Louis died young, as did the 14th-century Catherine of Siena, who, unfortunately for us, died the year Bernardino was born. What a fearsome pair those two would have made! Like him, she was considered by many a crackpot; like him, she preached all over Europe to multitudes (highly unusual for a woman); and like him, she caused apprehension in Rome. Partly this uneasiness might be due to the fact that Catherine’s pen was as mighty as her word, and she thought nothing of deploying both against popes both in Avignon and in Rome. Here she is writing Pope Gregory, telling him to get himself back to Rome where the papacy, in her less than humble opinion, rightly belongs: “Don’t be afraid! Do something about it!” “Be a courageous man for me, not a coward!” “Well, I assume as much poison can be found on the countertops of Avignon or any other city as those of Rome!”

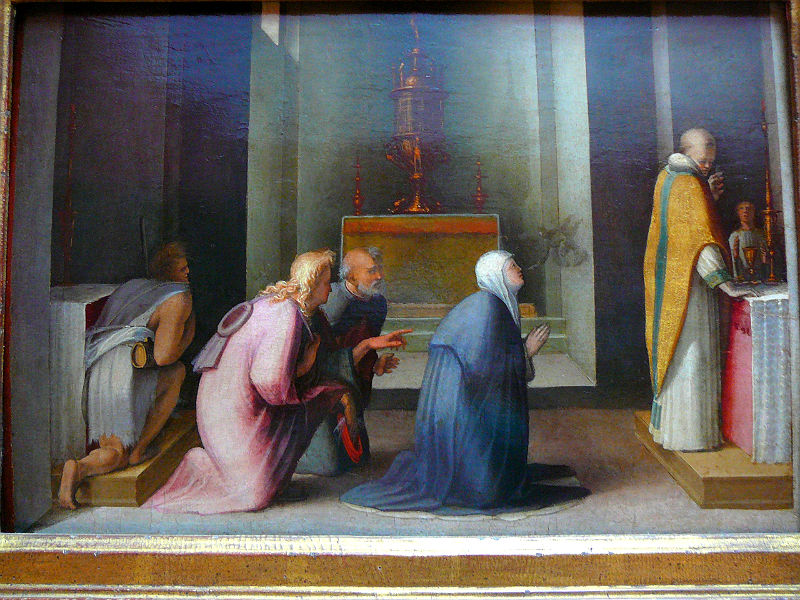

The Miraculous Communion of St. Catherine of Siena by Domenico Beccafumi

The “vigor and strength or her character and writings” are belied, says Kiely, by the “insipidity of the portraits that were made of her.” Indeed, the illustrations Kiely includes, by artists such as Andrea Vanni, Giovanni di Paolo, and Sodoma, are of a spectral creature–pale, pious, stooped, mute, and even fainting. In fact, as her letters to the pope demonstrate, her particular admonition to both men and women was to act virilmente, like a man– as we might say, “man up.”

Catherine, in some legends, receives the Stigmata, the wounds of the crucified Jesus. If indeed she was so chosen, she hearkens back to perhaps the most cherished of all saints, Francis of Assisi, the beloved poverello, who in 1222 received the Stigmata. Or did he?

…did it really happen? If so, why? Why Francis? Was he a masochist? Was he being rewarded by a gracious God or punished by an internal demon? Did his followers invent the whole thing?

“Why do we today prefer not to think about it, especially in relation to such a nice and friendly saint?” asks Kiely, who, with “an easy conscience,” admits to choosing Francis as his favorite saint.

Ecstasy of Saint Francis by Caravaggio

With the exception of Jesus himself and perhaps Mary and John the Baptist, no sacred figure in the Christian pantheon has been painted and sculpted so frequently, so lovingly, and so carelessly. From Assisi to Beijing, one finds painted tiles, figurines, holy cards, and garden statues with blurred and crazed features that make the “little poor man” look like a poor little clown or alien or survivor of a disfiguring accident. Yet there is the tonsure, the cord around the waist, the bare feet, and a bird on the shoulder. So it must be Francis.

Space does not allow us the luxury of discussing every chapter in this banquet of a book. Think of Saint Augustine with a toothache; of John the Baptist as a hermaphrodite; of the child Mary in Titian’s heart-stopping Presentation, and later, as the columnar goddess in Piero della Francesca. Kiely has given us a banquet of sweets and a variety of nuts. All of them holy.

To comment on this book review, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting reviews such as this one, please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link