by John Henry (June 2021)

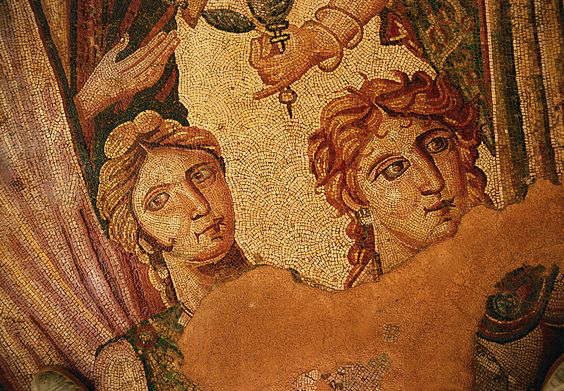

Achilles at Skyros, Villa La Olmeda, 4th C AD

I encountered the ancient floor mosaic while walking in archaeological ruins in Turkey during my childhood. If you have ever ‘stumbled’ upon an open-air floor mosaic it is like discovering the handiwork of an alien race. Many open-air sites in Turkey are not protected from the effects of weather or larceny. Contained within ancient settlements are stubbed walls of weathered stone, ruined features of temples and fallen columns; some re-erected as in the Library of Celsus in Ephesus. To discover a nearly intact mosaic amongst all the rubble is a wondrous contrast that stuns the imagination.

.jpg)

In the residential areas especially, ongoing excavations yield treasures that are testaments to craftsmanship and exacting artistry and geometry. Appropriated ancient marbles, building stone and statues were ground down or refigured into succeeding generation’s urban and private fabrics from Rome to Baalbeck. The most enduring, detailed, and colorful remains of these cultures are floor mosaics, which even after thousands of years of rain and sun, offer up their vibrant and ingenious geometries. They are astoundingly preserved.

.jpg)

There is so much history in the current Turkish state—from the newly found prehistoric Gobeklitepe to Catalhoyuk to Nemrut and later Greek and Roman settlements including Didyma and Ephesus—that it can overwhelm sensibility. Succeeding cultures build on top of each other and side to side. The lush Hellenistic 2,200-year-old design above was discovered in Zeugma in 2014. [“Turkey” was named after the Ottoman occupation dissolved following World War I, but it was previously known simply as Anatolia, a region home to Neolithic settlement, Hittites, Lycians, Parthians, Greeks and Romans, and finally Byzantines. The current modern country has no real connection with these ancient peoples, only to the Islamic state which preceded them.]

.jpg)

.jpg) The art of the (Western) ancient world is truly magnificent. When Rome was sacked, many of its ancient Greek and contemporary Roman treasures disappeared or were destroyed. Michelangelo was supremely impressed and influenced by the discovery of a Greek baroque era sculpture in 1506 known as Laocoon and His Sons. Three figures are writhing with serpents depicting an historic Trojan myth. The Renaissance-era reworked, and imaginatively restored composition appeared at right (photographed ca. 1845-55). Years later one figure and several pieces were removed to show its original state.

The art of the (Western) ancient world is truly magnificent. When Rome was sacked, many of its ancient Greek and contemporary Roman treasures disappeared or were destroyed. Michelangelo was supremely impressed and influenced by the discovery of a Greek baroque era sculpture in 1506 known as Laocoon and His Sons. Three figures are writhing with serpents depicting an historic Trojan myth. The Renaissance-era reworked, and imaginatively restored composition appeared at right (photographed ca. 1845-55). Years later one figure and several pieces were removed to show its original state.

Unlike the earlier static archaic statues (kouros) that were influenced by the somewhat rigid Egyptian hieroglyphics figures and Persian carvings, Laocoon is the epitome of representative figurative sculpture by late Hellenic artists that brings expression and movement—life—to a work of art. The sinews, veins, musculature and skeletal structure below, facial expression, and general proportions rival or exceed any succeeding representative figural sculpture from the Renaissance forward!

.jpg)

I offer this example of fine art at its apogee only to show that the same effort can be traced over hundreds to thousands of years regarding pottery, painting, sculpture of all kinds, and architecture. There are humble beginnings, and then a flourishing of technique. What is so remarkable in this example is that this effort is rarely matched by contemporary artists. One could argue that current literature and fine arts and architecture have been modernized, abstracted, abbreviated, and in our woke culture—deemed superior to anything created beforehand.

Early Roman mosaics were copied and expanded from Greek finds (example,right). Some were roughly executed; others were developed with exquisite results. The final product was qualified most likely by the budget, time allowed, materials available, and technical ability of the artist. At the beginning, colored stones were chipped into small pieces. Later, ceramic with color was fired. Not all the workers in mosaic were well travelled to have seen and compared samples from houses or temples even several miles away, so there was a learning curve and only much later during excavation and documentation could these works be compared. Over time and weathering, the brighter colors of the stones and ceramics would have faded. In some cases, coloring was completely washed out. Consider that for hundreds of years archaeologists and historians believed that the white marble remains of the Parthenon and most ancient Greek sculpture were void of color. In fact, organic derived colors were applied to nearly all sculpture and architectural elements. They were only ‘discovered’ using spectral analysis. Eyes were detailed, fabric painted, bodies were flesh colored.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The above mosaic is a nearly intact floor of a Roman villa, preserved in a museum in Hungary. Notice that is has similarities to a carpet with an edge pattern that follows its outer boundary and a truly inventive geometric system throughout. It was created for a rectangular room with a curving apse at the far end. Symmetry and polygonal sections mark this example. Other mosaics have a panoply of human and animal figures, flora, and even scenographic depictions. This one is strictly geometric.

To say this was a complicated effort is an understatement. Exacting widths of borders, centers, interlocking themes, etc. means expert artists were involved who could lay out the schematic design first and follow through, building the composition with great precision.

Lighter and darker pieces could simply be used to show an outline of a simple pattern (the floral in bottom rectangle) or a 3D interlocking mesh resembling a basket weave. Four large octagons contain parallelograms, squares, and remnant triangles around the four center circles. The entire composition mesmerizes now as it did over two thousand years ago. You can see under the forward circle a square border with a walled motif created with lighter and darker tesserae (often rectangular pieces) indicating a walled space. See the four-sided ceramic pieces in this detail of the apse section, and notice the color variation:

Mosaics are hand worked pieces of ceramic, stone, or glass held together by a binder (mortar or plaster). They were applied to walls and ceilings as early as Mycenean Greece, adopted through parts of the Middle East and Europe (Roman Empire regions) and then slowly discontinued during the Renaissance. There are modern mosaics that are now made of nearly any metal, stone or glass, or found materials. In order to maintain a level stone floor above grade in multi-level buildings and include a somewhat permanent wearable pattern and color, builders in the 1500s to 1600s set pulverized/remnant stone (marble/granite) and ceramic into a cementitious binder, polishing the surface, which resulted in the terrazzo floor. Early examples, such as this one in a Venetian Palazzo, included hand laid mosaics. Later, marble and terrazzo were the preferred flooring:

Greek and Roman mosaics offer glimpses into the humanity of the populace, as this portrait of a lady in Pompeii shows so well. Notice the finely rendered eyebrows, full lips (painted), the blush on the cheeks, the simple hairdo, extravagant clothing, and jewelry.

The art of mosaic was more permanent and took longer to create than painting.

Whoever commissioned a portrait of this type was keen on an accurate likeness and wanted to preserve the image longer than paint on plaster or wood would allow. This was a rich patron for the artist.

The people on the Mediterranean subsisted largely on sea food and agricultural produce, thus marine life was often a common theme, as well as birds and flowers/trees.

.jpg)

.jpg) This Roman mosaic (above) from the House of Orpheus (dining room) in Volubilis, near Meknes, Morocco indicates that the artist (and well-travelled owner) had seen elephants even as well as deer, monkeys and other exotic fowl. The colors are still vibrant, even though unprotected from the elements. Rich pattern abounds.

This Roman mosaic (above) from the House of Orpheus (dining room) in Volubilis, near Meknes, Morocco indicates that the artist (and well-travelled owner) had seen elephants even as well as deer, monkeys and other exotic fowl. The colors are still vibrant, even though unprotected from the elements. Rich pattern abounds.

Notice that just the lower walls of the house remain. There are no doorways or windows, no roof left. Yet the mosaics stand the test of time. A detail from another mosaic in the same town shows a boy with his pet.

.jpg)

All subject matter was explored, including mythology, human relationships, battle, and simple landscapes. In this 3rd to 4th century Roman mosaic, the Greek Medusa myth is explored with a rich terra cotta coloring accented with azure. Mosaics are seen in Islamic art and architecture. In the Byzantine era mosaics were installed on vaulted ceilings, walls and columns of cathedrals, monasteries, and some public buildings. Because so many of the artists were isolated in their regions, each city would maintain a characteristic style. The coloration and patterns of this mosaic in Sicily (below) is unlike others of the same era in nearby communities.

.jpg)

The geometric precision of a large number of Roman mosaics is startling to comprehend. Notice the degree of perfection required in the plotting of curves and the foresight of coloration in this Roman mosaic archived in a museum in Corinth, Greece (left below). A variation of this mesmerizing geometric theme with the Medusa head at center is apt, to describe the trance that followed when gazing upon its face before turning to stone. This predates our modern op-art of the 40s- 50s—a throbbing or vibrating pattern that swells or warps.

In southern France, mosaics were discovered in the ancient city of Ucetia. This one includes the large ‘Greek key’ motif based on the Meandros river, which is named for its constantly changing course. The blue waves on the border are attributed to earlier Greek motifs which were readily adopted by the Romans.

.jpg)

Finally, enjoy this multicolored wall mosaic masterpiece discovered in the House of Neptune and Aphrodite in Herculaneum. Dated first century AD, its namesakes are featured in the center with an undulating fan pattern above and framed with fancified Corinthian columns. The artist created a 3-D effect with the umbrella fan by going from lighter shades of blue to darker. The Greek wave here is in a reddish hue. The artist fills the space between the figures and columns with inventive geometries of curving stems and flowers. Even the mythological figures are given a glistening effect to make more life-like in depth and form. The palette of colors is truly remarkable.

.jpg)

__________________________________

John Henry is based in Orlando, Florida. He holds a Bachelor of Environmental Design and Master of Architecture from Texas A&M University. He spent his early childhood through high school in Greece and Turkey, traveling in Europe—impressed by the ruins of Greek and Roman cities and temples, old irregular Medieval streets, and classical urban palaces and country villas. His Modernist formal education was a basis for functional, technically proficient, yet beautiful buildings. His website is Commercial Web Residential Web.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link