A History

by Justin Wong (May 2023)

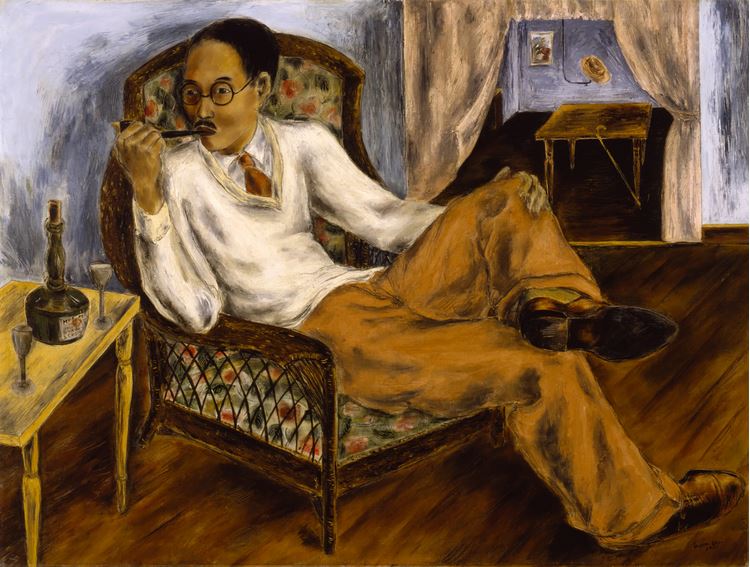

Man in his Studio, Bumpei Usui, 1930

Their history is poetry because nations in their infancy do not write their history: they sing it. —German Arciniegas

Part 1

Being not permitted to speak posed various problems, especially when one is an historian. This was the predicament of Xi Tian, the historian who sought to write a critique of his home country—China —the place he lived. Such an undertaking was not entirely unthinkable, amongst past and current generations, as long as they were in exile; Chinese nationals who upped sticks, emigrating from the place of their birth to liberal parts of the west, where speech was consequence-free, where it is protected in law.

In exile, one could denounce the state and not be locked away. In exile, one could express their innermost feelings and not be found dead in his apartment.

For Xi Tian, though, emigration was out of the question and freedom found in a country apart from China constituted wish fulfilment, not reality. Though what remained for him to do? Give up the thing he assumed to be a noble and exalted task to conform to the party line? Write drab books that were both predictable and perishable? Or, should he do something else? Xi Tian was lost in thought, wondering what that might be.

Part 2

We tend to think of the study of history as a drab matter of fact endeavour, the remembrance of dates and key moments in certain eras—events that forever changed life as we know it. But from where did those moments come? We seem to consider the fact that our world is markedly different to the one of centuries past as being purely fortuitous; as if it changed by chance. If one war didn’t happen at a particular time, then a consequence wouldn’t follow. Or, if the oppression of a people was so widespread in the country and cities where members of the dispossessed dwell, then they wouldn’t uprise in the spirit of revolution. I want to present you with an alternate explanation, another way of seeing.

History isn’t merely a random set of events, thought as presumed, to move on a whim. For the idea or imagination is the principal mover of history. Karl Marx said was “The philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways. The point is to change it.” This is so asinine that one doesn’t know quite where to begin. The idea that philosophy of thought has not left its mark upon the world is wildly untrue.

Certain laws to do with justice in the western world have taken their cue precisely from the Bible: how to punish the offenders; the mercy that should be shown to them; under which circumstances they should be let free (if they should be let free at all), and whether their blood should be upon them.

Thomas Paine had a vision of a society of universal suffrage. His book, Rights of Man, was considerably influential to the founders of the United States of America. The same could be said of Simón Bolivar, who liberated large swathes of the Latin American world from European rule, under the sway of Montesquieu, and other enlightened advocates of liberalism.

In both those instances, ideas weren’t merely passive or retrospective, but rather a creative part of the historical process. It is important to note that the world envisaged to have things like rights, freedom, and equality such as never existed before, requires visionary insight. A visionary insight that will materialise into reality through revolution, when the old oppressive order is shed like a serpent does its skin.

This proves that imagination plays a far more pertinent role in the formation of the world than was previously assumed. There is more fiction in reality than in novels, romances, and plays. When Shakespeare claimed the world to be a stage, he was right in more ways than one. For to live in society is to live in a kind of dream, one that we all dream collectively.

If the world is a glorified work of fiction, why should history be any less than life is?

Part 3

After Xi-Tian devised his plan to write his truthful and honest history of China, he was a mass of nervous emotions. He did not know how to proceed. First, he felt certain he must write his critique of modern China, consisting of the world a few years before his birth to the contemporary era, as if it was a foreign country. Then he decided even that was incorrect, since someone might notice that his critique would be written about China, afterall, and would be tantamount to slander on a national level. No. He decided that instead of writing his critique of his homeland not being China—or another country—he would write it about a completely fictional one.

I understand that to the reader in the western world that this kind of thing might sound absurd. In the free west, one is encouraged to learn much about the broader world beyond one’s national borders. The inhabitants of China, at least from birth, are not reared to be this urbane. It is not uncommon for certain Chinese nationals to go from the cradle to the grave never once leaving the city of their birth. Of course, they have heard of the wider world, outside their own, they have seen images of it, in much the same way that most people have stared dumbfounded at the night sky. You see lights that sparkle before you but don’t know where to place them, be they near or far, what solar system, or galaxy they are part of. The way the layman—the person untrained in astronomy and its arts—views the cosmos, is the way that the average Chinese person views the world. He knows the world through nothing more elaborate than hearsay. This is not to denigrate the Chinese person, to show him as being less than sophisticated through nothing other than his race. Rather the system of government—as run by the Communist Party—fosters this kind of ignorance. They want its population to be unknowing of the world around it.

Xi Tian saw elements of this in life. He remembered listening to a conversation between a man in the street who was talking to a black foreigner. When the Chinese man asked him where he was from, the foreigner said that he was an American, to which the Chinese man responded, “I didn’t know that they had black people in America.” He said this at the time when Obama happened to be the president.

When Xi Tian reflected back on moments such as this, he thought that he could get away with his plan. Writing truth as fiction would allow him to get over the problem of censorship that would silence a critical voice such as his, It would put his voice, his book, in the company of the prime mover of the historical process: the fantastical imaginary things—those not of this world.

This of course wasn’t the only thing he had to consider—whether he could pull the wool over the eyes of those ignorant of the broader reality of space and time outside the republic. By what other means could he be found out? Would the description of his imagined world and his lived reality be so similar that anyone with any sense at all could tell that his talking of one thing, was a mask for his talking about another?

He went out of his apartment, into the evening streets which were crowded in this hour with people rushing by on bikes and foot. Numerous vendors were out in public, plying their trade, selling from numerous stalls, various snacks (steamed bread and pancakes), to people making their way home at this time from school and work. Xi Tian was oblivious to the life going on around him, the people scurrying to and fro through the streets, the blinding headlamps of passing cars, the groups of dancers on the corners, shaking off the cold in the chill autumn temperatures.

He went straight to a noodle restaurant, and ate a bowl of beef noodles. He further reflected on how he should write about this fictional republic, a country like his in kind though not in name. He pulled out a notebook that was trapped in the recesses of his rucksack, and began to jot down a few ideas. From this he came up with a name, Wuchuguo. This is what he would call his fictional country.

Part 4

He was sure to makes his history vague unless there were any striking similarities between China and Wuchuguo, reality and imagination, the place he was, and the place that wasn’t. The substance of the two histories, although different in terms of names, places, dates, and principal figures—was the same in spirit. The history of Wuchuguo, much like the country of his birth he was frightful to pour scorn upon, had a new era birthed in the violent upheaval of blood-soaked revolution. The revolutionaries, at least before the transformation, were under the spell of radical Utopianism. The revolution, if it was to occur, promised that it would solve poverty and inequality, putting a stop to the greed and obliviousness that characterised their society’s upper echelons.

They weren’t the only group of people with such radical sentiments that stormed the capital to bring an end to what they thought of as an oppressive regime. Other groups, those with different ideologies who all had similar goals of taking down the Capitalist order, weren’t as successful as the group of revolutionaries that were so in the summer of 1956, known as the Wuchuguo Lions. The other groups that carried out failed coups, were caught, rounded up, and shot out in the public square like rabid dogs.

The Wuchuguo Lions, and their revolutionary organisation, along with their charismatic leader, Zurasta, knew that this was going to be a risk, when their groups of guerrillas embarked for their journey of no return so to speak. They knew that if this did not go to plan that they could not go back to their previous lives. The current regime had to lose or else they would.

It goes without saying, that through much trepidation, they went through the plan to create their Utopia, a plan that was successfully hatched, if not why else would this be written about it?

Zurasta, the aforementioned leader of the coup d’etat, became the dictator after the revolution. The reason why this was successful, the reason why so many of the Wuchuguo population didn’t rebel against the sudden swift transformation of their country, was due to the timing of the coup. It was a moment in history when the spirits of the population were particularly low. Poverty had captured the majority of the people, even worming its way into the small middle classes. People were less liable to push against change when all were in agreement that change was the thing that was needed.

The revolution brought with it changes, and the new socialist government led by the Wuchuguo Lions needed to let it be known, that they ruled by an iron fist. The law of the previous order, although not liberal by first world standards, became draconian as if by overnight. One night, the sun went down on mercy, and rose the next day in injustice.

Rounded up were the people who were seen to be subversive, or counter to the society being formulated before them. Poets, journalists, capitalists, and intellectuals all received a knock on the door in the dead of night. They were tried in mock courts. It goes without saying they were almost all found guilty of their crimes. Some were imprisoned, some were sent in exile, others were executed. This depended on the severity of the said crimes, how dangerous they were to the continuation of the newly established order.

As soon as these men who were seen as being contrary to the new society were rounded up and treated as examples, the rest of society fell in line.

The newspapers, once known for free enquiry and criticism, began to adopt the ideology of the party—that of the Zurasta regime. The newspapers began to be told what was true and what was false, what was worthy to be printed and what was worthy to be left out. Freedom of conscience—a once cherished idea—vanished like a teenage girl who had become pregnant out of wedlock.

The quashing of conscience was something that was missed if not expressed, at least not in public. It was talked of in private amongst the populous, incessantly so. Even so, the people of Wuchuguo silently acquiesced to these changes, as the new regime promised things that people looked forward to.

As the years eventually passed, none of those things that they desired were given. Their world, if anything, descended into chaos. The people who were promised the fruits of a prosperous and equitable society felt mugged.

Zurasta had it in his mind a few years after his ascension to power, that the population of birds were responsible for the destruction of their crops. As a result of this he made a law that gave the people—farmers, mainly—the power to shoot birds out of the sky that were known to gorge on crops of wheat, corn, and barley. The farmers in rural areas dutifully followed this advice. Expeditions of hunters waded through vast swathes of the country with sticks, slings and arrows, and rifles—executing anything that looked as if they might ruin the flourishing provisions.

One may doubt the effectiveness of such a policy, for how successful could man be in shooting every bird from the sky—as if this were a symbol which showed man’s dominion over the natural world? One might be reminded of King Canute’s commandment to the tides, which turned out to be oblivious to earthly power.

To some degree, though, Zurasta was successful in his ploy. Significant populations of birds were culled from the countryside. Birds that were known to pick away at farmer’s crops vanished, but not all was then well in their world. What was put in its place as a result of this recklessness was worse than the effects of a few birds nibbling away at their crops. The crops began to die of blight. The birds that many thought were eating away at the wheat, corn, and barley, were eating the insects also, which were the actual threat to their crops.

In the shadow of the bird genocide, the country of Wuchuguo was overcome by a terrible famine. There was scarcely enough bread, corn and meat to go around the population. This travesty was most bitterly felt in the heart of cities. It was there that sights of desperation were seen in the most horrific conditions. As a result of this catastrophe, theft increased suddenly; people who otherwise lived lives of stability began to hawk their possessions in the street for a bowl of soup, or something of similar worth.

These sights, although terrible, didn’t begin to scratch the surface of the depravity. Women began to prostitute themselves in large numbers. The cities of Wuchuguo were never free of such things, although this now appeared prostitution was the rule and not the exception when it came to work for women. The situation was so dire, that women were not only plying this trade for pounds and pence, but bread.

To look at the country in light of the famine, the project of socialism seemed a blunder. Zurasta thought as much, and believed history would judge him for the things he wrought—the hunger, the misery, the vice. It was the time of Wuchuguo’s famine that Zurasta was at his worst psychologically. He was never a man free from paranoia, and this was reflected in his policies—how he implemented a vast network of spies to listen in to what was happening in society. Now, this sense of suspicion was amplified. He became mistrustful of those close by, thinking they were all secretly plotting against him in order to bring his regime down. He thought that their political project had become so intolerable, that the agreed-upon sentiment was that it should end, that the public should have his head. Some of you who are familiar with Freud and advances made in the field of psychiatry, might be aware of the concept of psychological projection—where one can see their faults in another which they are blinded from seeing in themselves.

Despite the problems eating away at their regime—famine and the possibility of dissent—things began to find its footing once again. Though, why didn’t the government fall to the ground, specifically when one examines the conditions? If one is to look at history, others have fallen for lesser crimes. Some historians have noted that Zurasta’s regime didn’t lead to the people storming the capital demanding change because, during that century alone, Wuchuguo had already experienced three revolutions, along with an occupation as the result of war. The last thing they wanted to do was to experience another one, particularly when it was producing many of the same results: disaster, poverty, starvation, and despair.

But even after the famine was over, when order of a sort was restored, and the once-vanished birds were flying again through the rural skyline, there was a tendency to think that the project to achieve a society that was a paradigm of the utopian socialism they held so dear in their youth, had failed. Looking at the way in which their society functioned, it was nothing like their dream. their youthful visions. Reflecting on the politics that were diligently implemented, they wanted to know, why? After committees of people were formed, and people mused upon the question, the only thing they could think of was history.

The reason the revolution wasn’t successful was because the people of Wuchuguo were still very much under the sway of traditionalism. Ancestral wisdom still played a major part in the formation of character. It became decided on by the upper echelons of society that this needed to be eradicated. Though how to do this?

They hatched a plan to send many of the children of the bourgeoisie away to the countryside to live alongside members of the peasantry. This was done to purify their souls that had been tainted by the capitalist system. After several years of being in the countryside, they would come out cleansed of the disease of capitalism and find themselves more in line with revolutionary values.

This policy was implemented across the country: north, south, east and west, though no one was sure how successful this was, if at all. People were uncertain if this suddenly made people less traditional and capitalistic, or if its effect was benign. Effective or not, the policy was carried out for close to twenty years, stopping only at Zurasta’s death.

After his death, it was adamant that the regime and the party move forward. The person who was put in Zurasta’s place was a young protégé who wormed his way up the party. Although he was seen as young and inexperienced by some, he was also seen as vibrant and energetic by others—exactly what was needed to revive faith in the new society. His name was Mendes and, like a lot of leaders who promised much, he was loved at first. His legacy was nothing to write home about, though, and instead of promising an egalitarian society where the wealth was distributed equally, many of the same problems carried on from the previous period. While the regime wasn’t a perfect mirror image of the disastrous era of the Zurasta regime, it added to the disaster. It also became even more paranoid.

Networks of spies began to follow around people who were suspected of being political enemies. Soon this sense of suspicion began to spread outwards to the rest of society. Phones calls were monitored, mail was opened. This is not all that remains of the legacy of Mendes. Mendes, the second leader of the revolutionary party, was responsible for a series of economic reforms, which helped to grow the country’s economy.

These changes could hardly be classed as being trivial, historically speaking. For these transformations changed Wuchuguo from a failing economy to a player on the world stage. What were these changes that transformed the economy? If one must know, they consisted of the principles of capitalism. How could they justify embracing the introduction of policies they were trying to move diligently away from? This was justified by it being a form of capitalism that was not controlled by the caprices of corporations and self-interested financial institutions, but by the government. This is state capitalism.

This wasn’t a complete abandonment of their revolutionary socialist principles, but an acknowledgement that it would take time for their country to achieve true equality. Nevertheless, Wuchuguo, began to grow economically until Mendes’ death. At that time, the leader was replaced by Paolo, who continued where Mendes left off, growing the nation’s economy whilst secretly betraying the principles of the revolution.

Part 5

Xi Tian published this history with a degree of trepidation. Were they—meaning the Chinese government—going to figure out that this was nothing more than an elaborate ruse, where fiction becomes a cover for history despite the book was presented as if a truthful account?

Maybe he thought that he did too little to cover his tracks. The fictional state of Wuchuguo shared so many striking parallels with China that it was obvious that one was naturally a substitute for the other. Nothing could adequately describe the anxiety that Xi Tian suffered during the days and weeks after this fictional history was published. He rarely went out, he grew suspicious. He thought figures were shadowing him through the city streets. He thought people going about their business were engaged in nefarious misdeeds. All of these things were delusions. But that didn’t mean governmental figures weren’t spying on him.

Part 6

Two weeks and two days after Xi Tian’s history of Wuchuguo went to the printing press and was distributed across China for the public to buy, he received a knock on the door. Some would say that this should have come as a shock to the system, seeing as two suited governmental figures imposingly appeared unannounced at the door of his fourth-floor apartment, but it didn’t to Xi Tian. He thought his subversive acts would lead naturally to this attention.

“Xi Tian,” one of the figures said.

“Yes,” said Xi Tian, in reluctant manner, fearful, though relieved that his activities had been found out.

“Did you write this book?” he said, handling a copy of the said volume.

“Yes.”

“Then we would like you to come with us.”

To this, Xi Tian knew better than to push back, assenting to their suggestions that seemed like commands. They walked down the steps of the apartment block, out into the bustling streetscape, with people going about their business, perfectly oblivious that this man might be marching towards his death. He thought that he could run away, or at least cry for help. He decided to go against such impulses. He complied, following the lead of these men and as they escorted him into the vehicle waiting for them with the engine running at the roadside curb.

The ride, it goes without saying, was slow and distressing. As familiar sights became more unrecognisable, Xi Tian’s engrained sense of anxiety intensified. The men drove him out to a building somewhere off the beaten track, in a place that seemed perfectly devoid of other life. He was led into this building, and was told to sit in a room by himself. This is where he assumed he was going to be tortured: threatened, have his fingers pulled back, humiliated.

It was a long wait from the moment he was brought inside, to the moment when two figures walked into the room to greet him. Xi-Tan was surprised when the two people came back into the room, they came in with a smile.

“Xi Tian.”

“Yes,” he said, not knowing what was going to come next.

“We, as members of the Chines government, have been deeply engrossed in your work. We can say we are fans of what you have written. So much so, that we are really interested in the country of Wuchuguo you have written about.”

“Really?”

“Yes, we think that they are true enemies of socialist principles.”

“Really?”

“Yes. Think of what you have written—how they started their revolution with high hopes of creating an equal world, a fair republic, and from there, look at what they wrought. They neglected their people, caused famines and death through misguided policies and, worse than this, they turned to the oppressive capitalist system as a means of solving their issues.”

“Well yes, that is so,” said Xi Tian, not sure what else he could add to this.

This conversation went on like this for a while, this was nothing as Xi-Tan expected. Instead of being castigated, he was honoured. Although, why was he so surprised, since this was his plan, afterall—to turn something that was so intimate and familiar as his country into a place that was distant, removed and imaginary—a foreign land that lived only in his mind.

After this initial meeting with government officials, things naturally moved upwards from there. His fame rose with the sales of his books. He was invited to events; he won awards. Xi Tian, a figure that was once snubbed by the mainstream intelligentsia was embraced by them as a historian of some note, not just by others of his field, but by philosophers, sociologists and economists also.

If this was the full effect of his publishing his account of the fictional republic of Wuchuguo, then he could be happy with his deceit. Unfortunately, it wasn’t.

Part 7

In the months after Xi Tian published the history of Wuchuguo, in the months after Xi Tian went from a relative unknown into a figure of distinction, there was a change of sentiment within the media in reference to the world outside China. It came as a shock to Xi Tian that the name of Wuchuguo was mentioned. This was subtle at first, a few jabs here, a few snide comments there. Although as time went by, these comments began to be turned into articles, into editorials. Massive critiques began to be directed to a country that was non-existent, its position on a map, nowhere.

Needless to say, despite the newfound fame of our hero, this made him uneasy for fear that he would be found out, that he would be denounced as a fraudster—the creator of an intellectual hoax. He thought the best thing that could happen was that this would blow over and that journalists would soon grow tired of what is going on overseas in distant countries that had nothing to do with China.

As much as Xi Tian wished this was so, the sentiment towards Wuchuguo grew even more vitriolic. Now open calls were being made to invade the country. This was because they believed Wuchuguo represented everything the Chinese government and, as an extension, the people were against. After all, Wuchuguo had claimed to stand for change, for alleviating the lives of the poor, for transforming their society from a decrepitude wrought by the corruption of capitalism to turning their backs on these principles. Why should any of these things be the concern of the Chinese government, specifically when this was taking part thousands of miles from where they were? The logical inconsistencies of their argument didn’t stop what happened next.

On a July day, the Chinese government declared war on Wuchuguo. This was enough to frighten Xi Tian, for they should discover that no place existed. He thought it appropriate to plan for his escape, however fruitless this might prove to be.

The Chinese boats set off from the shore of Hong Kong, destined to find the country that stood for everything they, in theory, were against. This was the way that they framed it, a country that was a threat to the Chinese way of life.

The boats set sail for the shores of Latin America, and the more they looked for Wuchuguo, the more Wuchuguo eluded them. They extended their search outwards—eventually scouring the entire globe until they arrived back to the beginnings, back to Hong Kong, where what awaited them was the source of their rage, even if their eyes that were too blind to see it.

Table of Contents

Justin Wong is originally from Wembley, though at the moment is based in the West Midlands. He has been passionate about the English language and literature since a young age. Previously, he lived in China working as an English teacher. His novel, Millie’s Dream, is available here.