by Martin Hanson (February 2018)

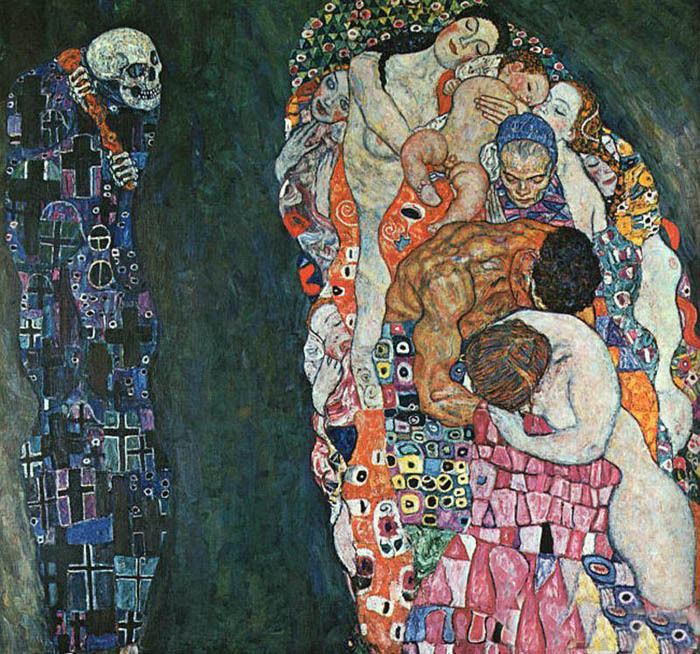

Death and Life, Gustav Klimt, 1908

.jpg) s Benjamin Franklin remarked: “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” While some manage to avoid taxes, death visits all of us eventually. Only a few generations ago, it came mostly in the form of infectious disease, and for women, there was the additional threat of death in childbirth. In England, a boy born between 1276 and 1300 could expect to live to about 30 years; today, UK life expectancy is about 80 for men, 83 for women.

s Benjamin Franklin remarked: “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” While some manage to avoid taxes, death visits all of us eventually. Only a few generations ago, it came mostly in the form of infectious disease, and for women, there was the additional threat of death in childbirth. In England, a boy born between 1276 and 1300 could expect to live to about 30 years; today, UK life expectancy is about 80 for men, 83 for women.

These extra years have come courtesy of science and its offspring, modern medicine. The discovery that communicable diseases are caused by microorganisms created opportunities for disease prevention. For example, cholera epidemics could be eliminated by the simple expedient of combination of sewage treatment and chlorination of public water proper supplies. Antiseptics, aseptic surgery, vaccination and antibiotics were other developments that saved lives.

Medical advances were not unalloyed for, accompanying this increase in life expectancy was a change in the pattern of mortality. Infectious diseases were replaced by diseases of affluence such as cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes, and degenerative diseases such as dementia. And survival to a greater age left people more susceptible to cancer.

Paralleling these changes in medical technology has been, particularly in Europe, a trend towards secularism and associated changes in attitudes to death and suffering. For many of those in the later stages of terminal illness, and for their families, the obligation to endure suffering is increasingly regarded as senseless.

The only non-controversial aspect of this issue is the inevitability of death. The divisive question is whether one should have the right to end it at a time and in a manner of one’s choosing in order to avoid unnecessary suffering. Except in a few countries, one has the legal right to end one’s own life.

But this was not always so. Since before medieval times suicide or ‘self-murder’ was condemned as a ‘mortal sin’ by the Church, and became illegal under common law as early as the 13th century. Offenders were denied a Christian burial, their bodies dumped in a pit at dead of night with no clergy, mourners, or prayers. What’s more, the deceased’s family forfeited their belongings to the Crown, reducing them to pauperism.

But that was when the Church had control over every aspect of people’s lives; since then, things have moved on, haven’t they? Well, yes, but not so far as one might think. As recently as 1958, Lionel Henry Churchill attempted to shoot himself after his wife died. He was found with a bullet wound in his forehead next to his wife’s partly-decomposed body. Doctors recommended medical treatment at a mental hospital, but magistrates disagreed and sent him to prison for six months. It was not until 1961 that attempting suicide became legal in the UK. Even today, in the 21st Century, a vestige of this medieval attitude to suicide persists in the phrase ‘commit suicide’. The word ‘commit’ has a connotation of an immoral act, as does the word ‘perpetrate’, which is why the Samaritans don’t use the term.

Since 1961, suicide has been legal in the United Kingdom. The right to die is now mandated by rules drawn up by the General Medical Council in 2010, according to which doctors much respect dying patients’ wishes if they do not want their lives prolonged. Thus, a patient has the right to refuse hospital treatment or food. This would seem to imply recognition of one’s right to autonomy. But the reality is different, as the following two cases make clear.

In his early fifties, Tony Nicklinson suffered a catastrophic stroke that left him paralysed except that he could breathe, swallow and move his eyes and eyelids, but his mind remained as sharp as ever. His only means of communication was by using computer software to convert blinks into letters of the alphabet. After six years, faced with the prospect of many more years of what he described as ‘living hell’, he petitioned the Supreme Court to be given help to die. His petition was refused, so he took the only option left to him; he stopped eating and died a week later. This particular case was the subject of a BBC Hardtalk documentary.

The case caused the former Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, to change his stance on assisted dying. Writing in the Daily Mail, he commented:

The fact is that I have changed my mind. The old philosophical certainties have collapsed in the face of the reality of needless suffering. It was the case of Tony Nicklinson that exerted the deepest influence on me. Here was a dignified man making a simple appeal for mercy, begging that the law allow him to die in peace, supported by his family. His distress made me question my motives in previous debates. Had I been putting doctrine before compassion, dogma before human dignity? I began to reconsider how to interpret Christian theology on the subject. As I did so, I grew less and less certain of my opposition to the right to die.

Quite different was the case of Avril Henry, who had been Emeritus Professor of English Medieval Culture at the University of Exeter until April 2016, when she killed herself in her home. At the age of 82, she had been plagued by chronic ear infections, tinnitus, cardiac and renal problems, swelling feet, double incontinence, arthritis, spinal degeneration, vertigo, and deafness. She wanted to end her life before it became intolerable. She had imported Nembutal, a lethal and illegal drug. At the inquest, her solicitor said: “Two armed police officers smashed a glass panel in Avril’s door and came into her house. She was very upset by the infringement on her personal space by the police forcing their way in”. But the police had not found all of it and she used the remainder a few days later.

Dr Henry’s suicide note was published in the press and I reproduce it here so that readers can make their own judgement about her mental health and decide for themselves if she was ‘vulnerable’:

SUICIDE NOTE

It is the evening of Saturday 16 April 2016. I am about to take my own life by swallowing Nembutal and then, to counteract the bitterness, a miniature bottle of Cointreau.

I am alone. The decision is wholly mine. It has the sympathetic, loving support of all my family, friends, members of the village, as well as staff and friends at Lords Meadow Leisure Centre, Crediton (where until last week I swam every day). All have known for a long time while of my intention.

This has been laboriously planned over more than 12 months. Written evidence for this is in this basin. It also appears from Feb 2015 in my Patient Records, as my GP can confirm. (He would have gladly have helped me but for the illogical, cruel British law which says suicide is legal, but forbids help to make it certain, swift, and painless.)

In case solitary suicide was not possible, I also obtained Approval of Assisted Dying at ExInternational, Bern, Switzerland (see copy of email from Madeleine Schleiss) but the journey in my unpowered wheelcair would have been difficult and horrible.

I very much hope that, since the evidence here shows clearly that no murder has been committed, there need be no Post Mortem, so that you can ask A. White and Sons (see Emergency Information) to collect my body from here a.s.a.p, as pre-arranged and paid for – like my burial in my orchard.

[her signature]

Emeritus Professor Avril Henry

P.S. If I have fouled the bath in death, please please be kind enough to wash it down: Dettol is provided.

The Nicklinson and Henry cases illustrate five deep anomalies in the law:

- While UK law gives someone with all physical faculties the right to undergo suicide, it denies that right to a person who does not have the means to achieve it.

- Most of the legal methods of suicide are violent, often painful, such as hanging, shooting, slitting of wrists, throwing oneself under a train or off a cliff, or starving oneself to death. Painless methods such as carbon monoxide poisoning deny the possibility of a death surrounded by family. Nembutal, which brings painless death, is illegal.

- If a person ends his or her life when family are present, family members run the risk of prosecution.

- People suffering progressive loss of capacity to exercise their legal right to suicide, as in multiple sclerosis, may be forced to kill themselves earlier than they would otherwise wish. In such cases the law is acting to shorten life against the person’s will.

- The existing law is in conflict with Article 5 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which states that: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

It’s clear that while suicide has been de-criminalised, it has not been freed of stigma. While one has the legal right to end one’s life, as present legislation stands, this right is a hollow one, for one clearly does not have the moral right to end one’s life. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the relaxation of the law against suicide in 1961 was the result of practical, rather than moral, considerations, and that criminalising family members who wish to say goodbye is an act of moral condemnation.

There are, however, slender signs that Church opinion might be changing, if an interview with Canon Rosie Harper is anything to go by. She was interviewed by Ruth Gledhill of Christian Today about the Falconer bill on assisted dying. The following is a transcript of that interview (unfortunately the video begins after what one assumes is the first question).

Harper: I support Falconer’s bill, really out of the depths of my faith; I think it comes down to what sort of a God you believe in. If you believe in a paternalistic, controlling God, then I can see you might have problems with this, but actually I believe in a God who is compassionate and essentially offers us free will, and aims to cause us to work collaboratively with Him, through creation in order to build our own lives. And the biggest choice [of all] that we have to make has to do with our eternal soul. I mean that’s at the heart of the Christian faith. And if He entrusts us with that choice, why would he then want to take away our choice, just when we need it the most?

RG: Hasn’t suicide under any circumstances always been counted as a sin, though?

RH: No, actually, it’s a relatively recent construct. If you go back to the bible, I think there are nine suicides in the Old Testament, and none of them are condemned, and you can actually make quite a cogent argument for saying that there were suicidal elements to the crucifixion; Jesus knew full well what was going to happen, and he did not count his life just simply as going on, more valuable than the higher task he had to do, so he went ahead, knowing that he would die at the end of it as he was brought to Jerusalem.

RG: Are you saying that Jesus’s death was the first assisted dying?

RH: (laughs) No, I’m not! But I’m just saying that there are greater, deeper moral issues about your life than making it go on and on for as long as it can possibly go.

RG: Have you ever been against it, has anything ever happened to change your mind?

RH: It’s more that theoretically, I was quite in favour, almost instinctively. And then, about a year and a half, two years ago, an uncle of mine developed a devastating, terminal brain tumour. And he decided that he wouldn’t have treatment, and actually, because he didn’t have treatment he had a good quality of life for three years. But he went through the whole process of signing up with Dignitas, and there came a point when he felt that it was no longer bearable to go on. And so he had his family round him, and they had beautiful music, and good wine, and he took the tablet and he died very peacefully and pain free. And everyone knew that the next two or three weeks until he would have died, let’s say, naturally, would have been utterly horrific as the brain tumour finally overtook him. So he had no choice about whether he would die or not; that was a given, but he was able to have some choice over the manner of his death, and his family experienced that as hugely loving, and they don’t have to live, haunted by the images of him final slipping away in a most horrendous way.

RG: The critics say, though, that that’s all very well, but the knock-on effect of permitting those kinds of death in this country might then open the way to other deaths that aren’t so voluntarily undertaken. What do you say about that?

RH: Well, fortunately we’re not the first country that’s done this. There are other countries that have done it – Switzerland, and of course now we’re talking about Oregon. And the statistics just don’t show that to be the case. In Switzerland they have better health care, better old-age care than we have. Old people live longer, so it doesn’t seem they are bumping off their grannies. And palliative care is of a higher order than it is here. And they’ve had fifty or sixty years working at it, and actually the number of people who actually undergo assisted suicide have remained very steady, sometimes a little bit down, sometimes a little bit up. And interestingly, I was speaking to the boss of Dignitas in Switzerland the other day, and he said that out of all the people who get what’s called the ‘green light’, in other words they’ve gone through the entire consultation process, and could do it if they demanded it, only nineteen percent of them actually do it. But for the others, the other, let’s say, eighty percent, it is a huge emotional help in dealing with their illness, because they know that if things really did get out of hand, and that was what they feared, there would be something they could do about it to retain control.

RG: So it’s nineteen—one nine percent?

RH: One-nine percent, yes.

RG: Now here, in this country, if it’s such a straightforward matter of justice for the dying, as you portray it, why hasn’t it happened before?

RH: It’s extraordinary; certainly, I can only speak from a Christian context, really, and it’s still a taboo subject, and I’m not entirely sure why. Linda Woodhead did some research through Yougov and she discovered that seventy five percent of Anglicans and seventy one percent of Catholics – lay people in the pews – are actually in favour, but that there’s a complete, um, yes, taboo would be the word about discussing it, amongst the hierarchy. I had an extraordinary experience at General Synod, and I was a complete rookie, and there was a debated the previous bill which was the Joffe bill, and everyone was standing up and saying the Christian thing, which starts with “We all know what a terrible thing this is” and it was completely condemning the Joffe bill. And with fear and trembling, because I was a complete new girl at General Synod, I got up and said the other point of view. And when I sat down my phone went completely mad, with people texting me, and facebooking me and so on, messaging me, from within the chamber of General Synod, saying: Rosie, I completely agree with you, but I don’t dare say it. I think it will change because the conversation is more enriched now, and we’re having events like the one we’re having tonight, and people are articulating what they feel, and that’s the first step, even if they’re against talking about it, it is really important.

What a stark contrast to orthodoxy! Whereas Mother Teresa taught that suffering is a “gift from God”, here is a compassionate human being, concerned above all, for people and when they suffer needlessly.

__________________________________

Martin Hanson was born and educated in the UK and emigrated to New Zealand in the 1970s where he taught biology for over 30 years. He is the author of a number of school textbooks.

Martin Hanson’s other work on NER.

To help New English Review continue to publish scholarly and interesting articles, please click here.