by James Stevens Curl (August 2021)

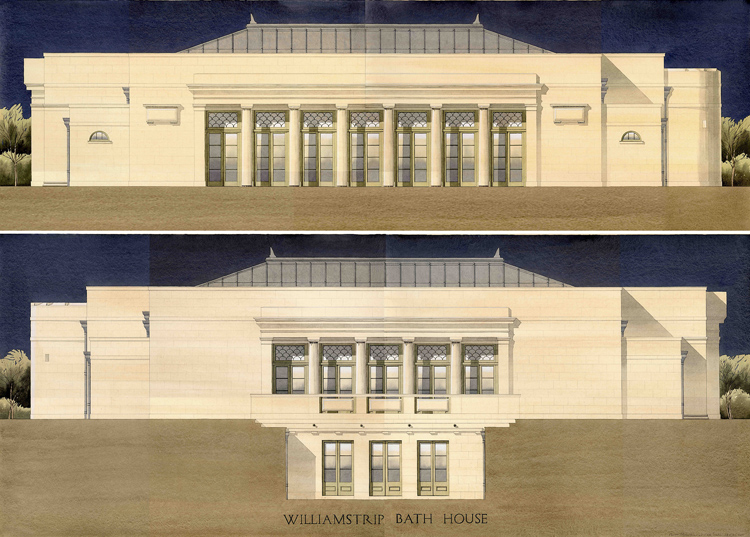

Architectural Drawing, Williamstrip Bath House, Craig Hamilton Architects

South-Africa-born Craig Hamilton, who, since 1995, has lived and worked at Coed Mawr, near the border between England and Wales, has demonstrated, again and again, the infinite variety possible when working with the rich, adaptable, and civilised architectural language of Classicism, not least when employing sculpture, embellishments, ornament, finely-wrought detailing, and natural materials, to create buildings full of deep meaning while avoiding copyism and arid pedantry. He has often collaborated with the Scots sculptor of genius, Alexander Stoddart, whose works display a deep understanding of culture, allusions, history, aesthetic depth, Classical precedents, and profound learning: his creations sing of beauty (a word eschewed by Modernists), intelligence, and much else light-years away from the shallowness of so-called ‘conceptual’ art as promoted by art-establishment apparatchiks who have been deeply hostile to everything for which Stoddart stands. Indeed, neither Hamilton nor Stoddart is concerned with concepts at all: as highly skilled professionals with principles, they are deeply involved with percepts, enchanting, graceful, heavenly, and kind.

Structures associated with death, such as mausolea, can give gifted, sensitive, real architects great scope to create exquisite and wonderful buildings in which sculpture and architecture are inextricably melded, each enhancing the other, forming a coherent whole, without any considerations of changes of use impinging on creativity. This marvellous book includes descriptions and illustrations of two of Hamilton’s mausolea, both in London cemeteries established in the 1830s, and both with apposite sculpture by Stoddart perfectly integrated with the architecture.

One mausoleum (2012-13) is set in its own plot surrounded by a yew hedge: that funerary garden (echoes of the Via Appia Antica, Rome) is entered through iron gates hung from two massive stone piers, each carved with panels depicting the ancient Grecian receptacle (lekythos) holding the liquid used to anoint the dead. The building itself, of very accurately cut stone with the finest of joints, is a masterpiece of Classical reticence, with minimal mouldings. In a recess opposite the entrance-gates is a relief by Stoddart showing two female attendants on the Dead draping a tall vase positioned off-centre: one of the figures holds a thymiaterion, a tall incense-burner, often associated with cemeteries and funerals in Antiquity (below, Left). On the far side of the mausoleum are bronze gates leading to the sepulchre’s interior: these have 8 panels by Stoddart, playfully alluding to the vital activities of existence and looking back to the precedents of Antique sarcophagi decorated with scenes of celebration in which putti play various parts. Gazing inwards is a female bronze figure carrying a lantern in one hand and the sacred flower of yellow Elysian meads, the asphodel, in the other: with her back towards the garden, she demonstrates her interest in the dead, so she is Mnemosyne, Goddess of Memory, one of the Titanides, daughter of Uranus and Gæa (below, Right). There are intelligent allusions throughout this and other great works by Hamilton.

It is unusual that Woodman, whose architectural education and career as a journalist have been conventionally Modernist, has taken such an interest in Hamilton’s work, and indeed written rather sympathetically about it in the volume under review, providing what are, on the whole, reasonably perceptive commentaries. However, the limitations of his Modernist background are sometimes painfully obvious: the lunettes on all four sides of the mausoleum’s attic storey are not ‘Diocletian windows’; bodies are not ‘interned’, as though they were going to be jailed, but are deposited in mausolea; the recesses in which corpses are placed in such buildings are not ‘catacombs’ but loculi</em>; he seems out of his depth with terms such as in antis</em>; and so on and so forth, which is a great pity, as one gets the impression that his heart is moving to the right place.

The other mausoleum (2014-17) is sited in St James’s Cemetery, Highgate, and this time the precedents of works by early twentieth-century architects on both sides of the Atlantic are clear (below, Left). Stoddart was responsible for the two bronze reliefs of vigorously modelled Fortitude and Faith on either side of the interior as well as for the beckoning angel standing sentinel in the apsidal end. In Stoddart’s work here can be detected infuences from the early bronze Icarus figure (1884) by Alfred Gilbert (1854-1934), and even from the creations of Lord Leighton (1830-96), which must cause problems for certain blinkered commentators.

Three glorious chapels are also included in this volume: that of St Rita of Cascia (2005-6) in the Scottish Borders, with an interior indebted to All Hallows, London Wall (1765-7), by George Dance the Younger (1741-1825); Christ the Redeemer, Culham Court (Berkshire), of 2008-15, with quirkily inventive Mannerist detailing by Hamilton, paraphrasing some of the sixteenth-century Florentine motifs employed by Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), and sculpture by Stoddart strongly influenced by the work of Bertel Thorwaldsen (1770-1844); and Our Lady at Williamstrip (Gloucestershire), of 2013-17, a stunning work, very tightly disciplined and exquisitely detailed (above, Right). Although the Williamstrip Bath House (Gloucs.) of 2010-12 is a very different building-type, the architecture is as geometrically tightly controlled as in the other works featured.

Influences on Hamilton are many, and his designs gain from his sound source-material, including works by Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863), Dance the Younger, the Slovenian genius, Joze Plecnik (1872-1957), Charles Henry Holden (1875-1960), John James Burnet (1857-1938), Lionel Godfrey Pearson (1879-1953), Harold Van Buren Magonigle (1867-1935), Edwin Landseer Lutyens (1869-1944), and other architects steeped in skills no Modernist ever bothered to acquire. Both Hamilton and Stoddart are men of immense learning and culture, commanding skills that have been almost bullied out of existence: neither of them subscribes to the current iconophobia; both appreciate and can create that which connects with the numinous mysterium tremendum</em>; and in times when the cultural Occident has almost been battered to extinction, and knowledge and study of it forbidden by those who insist on and indulge in Groupthink rather than mature individual reflection, it is a glimmer of hope that the sacredness of creative endeavour survives in such artists capable of making buildings that, Laus Deo, are in a manner refreshingly antipathetic to our barren, spiritually empty, creepily dishonest times.

This is a truly beautiful piece of book-making, superbly printed on fine paper, with clear reproductions of Hamilton’s exquisite drawings (some if his details are truly delightful), with magnificent photographs, the whole handsomely bound. Stoddart’s short, masterly, and brilliant Afterword is both funny and hits the nail square-on.

Woodman’s text, however, should have been carefully edited.

An earlier version of this review, commissioned by the Church Monuments Society, appeared in Church Monuments 35 (2020), pp. 210-212. Permission by the Society to re-use some of this material is gratefully acknowledged.

James Stevens Curl has been writing about the architectural and monumental celebration of death for over sixty years. His work has been honoured by The British Academy and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art of America.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast