A Nighthawk Flies into the Sunset

by Jeff Plude (May 2022)

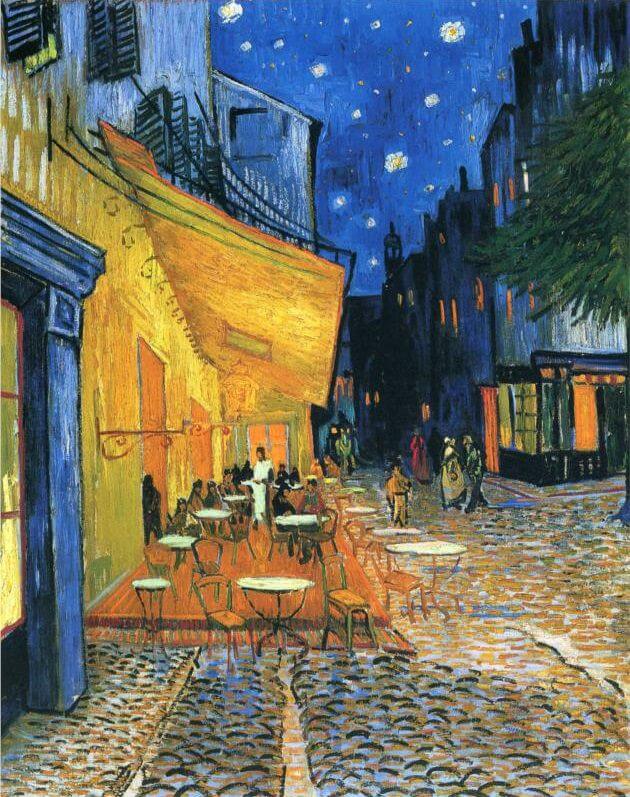

Café Terrace at Night, Vincent Van Gogh, 1888

A cousin of mine who is more like a brother used to call me “the nighthawk” when we were kids. He was like a little man himself back then—got up at six or seven in the morning on the weekend, ate fried eggs like our fathers. But I was a nocturnal animal. I wondered why everyone was so enamored with getting up so early when, unlike the night, hardly anything else was going on that interested me. Of course adults had to get up—my mother to make breakfast, my father to go to work.

The nighthawk is a curious bird except for its color, a darkish-gray mottled brown, though I don’t think I’ve ever seen one, at least consciously, though its habitat includes where I grew up. It has long legs and a mouth that opens wide to swallow insects as it flies, starting in early evening till just before dawn; it makes its nest on the ground; it sometimes perches on branches lengthwise instead of perpendicular. The nighthawk even appears in the Bible, in Leviticus and Deuteronomy, among the unclean animals that the Mosaic Law forbids the Jews to eat.

The human nighthawk is also strange, often viewed with disdain and even suspicion. I wrote a feature story about the nightshift once (I used to work all night myself one day a week at a convenience store during a summer break from college), and I remember from that article that about twenty percent of people are essentially nocturnal. The human body was designed to generally follow the daily rising and setting of the sun.

I know in my own case I was restless. I stuttered and because I had a brother who had what is now called “special needs,” and there was no or very little social services assistance for my mother at the time (most of the burden fell on her), I was left to my own devices. Even as a child I would lie there wide awake while everyone slept. My mind seemed to clip along. I would say something or other from bed, at least I must have because I remember my father barking at me from his and my mother’s room around the corner of the short hall: “Just close your eyes and go to sleep.” Easier said than done!

My father was one of those freaks that only needed a couple of hours of sleep a night. But he died at fifty-six of a massive heart attack, and I’m a few years past that now and still going.

When I was about twelve or thirteen and wanted to stay out later with my friends I asked him what time he had to be home at night when he was my age (practicing for my later job as a reporter). He said he didn’t have to be home at any particular time. So you could stay out however late you wanted? I was incredulous and envious. Yes, he said, but he had to be dressed and at the table ready for breakfast at seven a.m. and then work; so as long as he did that, he could manage the rest however he wanted. Now my father had seven brothers and sisters, so keeping track of their kids’ whereabouts was no simple task for my grandparents. During the Depression my grandfather ran a wood fuel business, which my father had to chop wood for full time when he should’ve been in high school, and at sixteen he started working at the local textile mill.

So he learned how to stay up and party, come home and get a couple of hours of sleep, then put in a full day of manual labor. He was also drafted into the Army near the end of World War II and said when he was on the front lines he learned to get by on a couple of hours of sleep a night, if that. It seemed to come natural to him, but when he continued it into middle age, along with some other bad habits, his body didn’t hold out long. He contracted diabetes after growing a big cannonball of a belly, weighing almost two hundred pounds at five-seven (like Napoleon, another famous light sleeper).

I was the complete opposite—I generally needed my full human allotment of seven to eight hours of sleep, though I pulled my share of all-nighters in college.

I was active during the day and loved playing sports of all kinds, but I liked staying up late. I didn’t want to miss anything going on in the adult world. My father would start snoring in his armchair in what seemed like seconds, but I would just lie in bed staring at the darkened blank ceiling and walls, or tossing and turning, my mind buzzing away.

Then in junior high I started sleepwalking. During the night my parents would find me standing at the front door or at the bottom of the stairs or opening the closet in the living room, which I had no memory of when I woke up. We were mystified by it, but it was no doubt anxiety. I was also small for my age and had to defend myself regularly in those days, the sixties and early seventies, when who could “take” who in a fight was a common topic.

My father hated how I got up late as a teenager, and we’d argue because he wanted me to mow the lawn in the morning but I preferred to do it in the late afternoon. Getting up early is a sign of uprightness and diligence, and there’s a self-righteousness about it. I recently read on a forum about a farmer who said he gets up at four every morning, turns on the lights in his house for the benefit of his neighbors, and goes back to bed till seven!

But when I graduated from college, I was finally going to have to give up my late hours, or so I thought. Much to my surprise my first real job was as a newspaper reporter, and I didn’t start work till three p.m.! Of course, even on nights when I didn’t decompress by hitting the local watering hole after the eleven p.m. deadline, I rarely went to bed before three a.m.

A short feature story recently caught my eye with the headline: “Forget 9 to 5: Dolly Parton reveals she starts her day at 3 am.” It almost seems like the night owl come full circle. She said she “naturally” wakes up at that time, “even if I’ve been up late.” She said she was “like my daddy,” a hard-working Appalachian. She said she does her “best work” early in the morning.

But almost all early risers seem to need a little pick-me-up. I don’t drink coffee, but I do drink tea, though I don’t have my first cup or breakfast until after a couple of hours of work.

I now get up at six in the morning on weekdays (an hour or two later on weekends), and after taking a shower, etc., I write. My wife has never been a morning person either, but she gets up with me. For a while I was getting up at five a.m. I had a military zeal about it, but instead of reveille I settled for an oldish digital clock whose alarm sounds like a weak car horn. I was determined to make up with a vengeance for all those years of staying up and sleeping in.

Why the conversion after nearly a half century of wallowing in the wee hours? It happened around the same time that I became a Christian. The Bible in fact does not have much good to say about the night. It contrasts light with darkness, especially in the Gospel according to John. Unbelievers are said to “walk in darkness.” Paul warns: “The day of the Lord so cometh like a thief in the night.” Revelation describes heaven as having no night.

When I stayed home I used to read, which is a soporific for many people but is like a shot of mental espresso for me; I used to watch TV, which I gave up altogether even before I stopped staying up late; I used to listen to talk radio. I still occasionally find myself in my study up a little later than I should be.

Most nights I’m now in bed by eleven. I still resist going to bed a little. I marvel at people like Harry Houdini, who I read used to hop out of bed at five a.m. raring to go.

Criminals, of course, come alive during the night, when they operate to their malicious hearts’ content without being observed, though that’s not as easy as it used to be with digital cams stationed around the exterior of many houses. My sister-in-law and her husband recently told me and my wife how footage recorded in the middle of the night showed a drunk outside their front door who then made his way to the backyard and tried to climb over the fence but couldn’t quite make it. Twenty years ago I witnessed two break-ins from the bay window of our apartment in San Francisco—one was in a car, the other in a bank of mailboxes in the apartment building across the street—both of which occurred at one or two in the morning.

The emotionally thirsty also emerge from their holes at night, when there seems to be a kind of black magic in the air. I’ve always liked “The Night Life,” one of Willie Nelson’s theme songs, his voice and lyrics evoking the forlornness of the carouser: “Mine is just another scene / From the world of broken dreams / And the night life ain’t no good life / But it’s my life.”

For a time I also believed the night was more conducive to creativity. What I mean is a sort of daydreaming, or perhaps similar to hypnagogic dreaming, the ones that flick on just before you nod off. I became very interested in dreams, the REM kind—for over ten years I recorded over a thousand dreams. But they didn’t yield much artistic fruit.

I even used to write late at night occasionally when I was a reporter; it was peaceful, I’d finish my feature story in my home office, then go into work early the next morning when nobody was there and type it in. Later when I was a freelancer I even wrote a rough draft of an unpublished novel from one to five in the morning for thirty or so days straight. I was trying to tap into the nether world of the subconscious, which the moon’s traditionally associated with as an archetype or symbol. The danger comes with the pure light of day, or the conscious and rational mind, when you find that instead of chiaroscuro what you have produced is more like phantasmagoria.

Many writers have worked at night, preferring it to the early morning darkness and dawn favored by most. For me the patron scribe of the night was Balzac, who wrote from one till eight in the morning. But he had to fortify himself with an amount of coffee that would keep a whole squad of graphomaniacs going; he died at fifty-one, a martyr to literary graveyard-shifters everywhere.

Surely the night has some redeeming qualities. While there are no doubt many insomniacs, there must be a few nyctophiles. What is it about the night that attracts some people? The mystery, the silence, perhaps a more elusive, starker beauty. The stars and moon—“the lesser light,” as it’s called in Genesis—have always captivated us here below.

An iconic depiction of the night is Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. While the main figure is the encompassing night, I think the blackness merely amplifies the emptiness of modern urban life. It shows none of the allure of the long stretch between sunset and dawn. I prefer Van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night, a print of which hangs above our dining room sideboard. It perfectly embodies both the electricity and the foreboding of the night: the tables on the patio, the burnt yellow lamplight glowing in the deep dark-blue backdrop that envelops the scene.

But I don’t really miss anything about the night—this nighthawk has flown into the sunset once and for all. I used to only see the sun rise occasionally, the handful of times I went deer hunting or when I was going to bed after having been out all night in my youth. Now in early spring I see the sun rise through the windows just before I sit down at my desk, a new glorious day before me. I never felt like that at night.

Jeff Plude is a Contributing Editor to New English Review. He was a daily newspaper reporter and editor for the better part of a decade before he became a freelance writer. He has an MA in English literature from the University of Virginia. An evangelical Christian, he also writes fiction and is a freelance editor of novels and nonfiction books.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast