by Robert Lewis (March 2021)

Humming Gold, Helen Frankenthaler, 1971

Abstraction allows man to see with his mind what he cannot see physically with his eyes . . . Abstract art enables the artist to perceive beyond the tangible, to extract the infinite out of the finite . . . It is the emancipation of the mind. It is an exploration into unknown areas. –Arshile Gorky

Not the result of chiaroscuro, nor a skilful dialectic of light and shadow (for these are still painterly effects) . . . a vague physical wish to grasp things . . . anterior to the perceptual order . . . the annihilation of the scene and space of representation. –Jean Baudrillard

The long day’s journey into the erudite midnight continues. Despite enormous willingness and tenacity, I am still unable to wrap my head around abstract art, persuaded that it doesn’t or can’t compete with figurative or didactic art. And yet a work of abstract, and not Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters, brightens up a living room wall—for the simple reason it is visually very pleasing while Vincent’s verité is downright ugly and depressing. So how do I respond to my many accusers who insist that I am stubbornly, tendentiously refusing to grant grade and gravitas to the beauty abstract art undeniably elicits? Especially since there is no finessing the precious St. Xupery thought that (paraphrasing) ‘the time I spend with my rose is what confers its value.’

In the spirit of full disclosure, I have indeed and in deed gone to considerable pain and expense to bring myself to faraway landscapes comprised of nothing more than a crest of dune set against a blushing blue sky. Or when in Italy, I automatically seek out the highest point in every town and village in order to aim my camera at the magnificent terracotta rooftops whose random shapes and organization suggest pure abstract painting. To these experiences I confer the highest aesthetic value measured by the time and effort spent in their pursuit. So why do I assign more value to nature’s abstract beauty than the comparable beauty elicited by abstract art? The short answer is that, however unfairly or irrationally, I am a product of my conditioning and cultural heritage (cognitive closure syndrome) and without apology, I expect man to go beyond, outperform, be better than nature. Henry James states that art arises when the image is superior to the thing itself. But that does not explain why the aesthetically pleasing lines of, for example, a sea-shell transposed to canvas should be less affecting than the actual shell? Or why do I insist on synonymizing abstract and decorative art, persuaded that neither attains to what is universally accepted as high art (da Vinci, Vermeer, Rembrandt, Cezanne)?

Throughout history we have accorded the highest praise and respect to our artisans and craftpersons, and the lasting achievements in the decorative arts: from classical Greek vases to Persian rugs to exquisitely wrought ivory carvings. We amaze at the workmanship and ravish the beauty the objects command. So far so good, until the line between decorative and abstract art blurs, when the latter begins to compete with ‘serious art’ and manages to claim a significant interval for itself in the history of painting, at which point art lovers such as myself discover they are unable to aesthetically rationalize Mondrian (geometric art) and Rothke (minimalism) sharing the same page as Rembrandt and Cezanne.

Decorative art doesn’t pretend to be anything other than its shapes, colour and design and the ephemeral aesthetic pleasure it offers. The viewer accepts its aims and limitations on their own terms. Both decorative and abstract art argue that the art item doesn’t have to communicate meaning to be meaningful. Instead of imitating, copying, describing the things of the world, both art forms are their own thing which doesn’t correspond to anything we know or recognize. Which begs the question: is it a sufficient condition that viewers or art critics need only be moved by the beauty of a work for it to be considered high art, to be exhibited in the world’s most prestigious galleries and museums?

In the history of art, abstract represents a radical break with all previous art in respect to content and preparatory protocol, best illustrated by analogy. The writer always knows what he is going to say in advance of what he writes. The act of writing gives shape to his thoughts and ideas which have anteriorly come to him. The same could be said of the figurative painter who knows in advance what he wants to paint before he picks up his brush and prepares his palette. What distinguishes abstract from all other art is that for the first time in the history of painting, which constitutes one single movement (Malraux: Voices of Silence), is that the painter need not possess any drawing skills, and he doesn’t know what he is going to paint until he paints it. In this sense, abstract is like jazz or any improvisational music where a change in a single note affects all the subsequent notes. In abstract, a colour or combination of colours suggest a complementary response: change the colour and volume and the other colours and volume adjust accordingly. The combinations and permutations are infinite. As such, the abstractor’s work is never done, until he’s done—and buried.

Abstract art represents a new language, or new way of seeing, albeit one the viewer is already familiar with through his experience with decorative art. It dispenses with most of the laws and principles that previously governed painting.

The abstract painter wants deconceptualize/deconstruct the things of the world so that we may discover the world anew, with astonished eyes, before things have been identified and named. No less than the philosopher, he is in quest of the pre-ontological, a primordial state of mind (being) that precedes meaning.

The abstract painter wants to silence language, to silence speech, to break the viewer of the habit of conceptualizing the world. He wants us to experience the world like the child who beholds it without having to assign a name or signification to whatever it is he encounters. In this sense abstract is dumb (not dumb as a measure of intelligence but prior to speech) and the viewer must dumb down (or dumb up if you prefer) to appreciate it. As T. S. Eliot says for great poetry, it communicates before it is understood. Abstract art is a mirror into the soul of the person looking into it: it appeals to the strictly emotive spectrum. Its unspecified aim is to awaken those a priori aesthetic categories of judgment that allow for the discernment of beauty.

However, unlike the writer and philosopher who deconstruct language so that we may eventually rediscover or respeak it with renewed vigour, in abstract art the world is deconceptualized and there it remains, unnamed; there is no speaking or rediscovery. There is no landscape, or bowl of fruit; the viewer remains mute, awakened to the plenitude of his feelings aroused by the work. Reduced to its lowest common ecstatic denominator, abstract art appeals to beauty for beauty’s sake, and since the artist chooses certain colours and shapes over others, it is a record of how he felt during the act of creation. As to what those feelings are, we can never be certain, in part because the viewer is mixing his own palette of life experience into the work, so the response to the work is directly related to the chemistry that arises between the artist and viewer. Thus, for the first time in the history of art, there need be no consensus of what a work means: meaning is in the mind or prerogative of the beholder.

Prior to abstract, the artist was responsible for a work’s content and meaning. The viewer was strictly passive, captive to the subject matter before him: Christ suffering on the cross, the plight of a raft on heaving seas, a wind rippling through a golden wheat field. Like no other art, abstract empowers the viewer, a development that reaches its apogee with installation art where the art goer literally places himself in the midst of the art work and reconfigures it as he moves in and about, interacting (con almádena) with it.

Should the abstract artist be miffed (“I get no respect”) that we either don’t get it or judge the genre inferior? Given that they are the first painters in the long and distinguished history of painting who bring themselves to the blank canvas without a game plan, without a vision other than to bring what they have started to completion, I’m tempted to conclude that their upset reveals a major short supply of empathy. What they are asking of the viewer is that he learn an entirely new visual language, not unlike asking a lover of hip-hop to learn the language of Bach, an undertaking that under ideal condition coupled with preternatural perseverance might take years—if not an entire lifetime.

If we don’t get it, I propose it is because abstract art has failed to articulate its founding principles, to make explicit an epistemology that would ground and legitimize it, and set in motion the rationale for its genrification. Consequent to this dereliction, some of abstract’s greatest exemplars have unwittingly contradicted the very essence of the genre, which is to deconstruct the visual world through a brave new visual language that speaks non-verbally, pre-ontologically. How do we account for painters inexplicably titling their non-conceptual art with recognizable names (concepts)?

If the title hadn’t been thrust upon us, we wouldn’t have any notion what Gerhard Richter had in mind in Ice 1-2 (1989). Just as we wouldn’t have a clue as to what de Stael’s Nice (1954) or Le Ciel Rouge (1952) refer to if he hadn’t named them as such. The works mentioned are pure abstracts; they have no objective correlative in the real world. It is almost as if the artists themselves aren’t sure of why and what they are doing, leaving the genre with the thankless task of trying to find its way without a mission statement—a sure recipe for hit and miss that throws the entire credibility of the movement into question. On the one hand, they endeavour to deconstruct concepts, and with the other hand, substituting Bic for brush, they assign concepts to works that have been totally deconceptualized. Small wonder abstract art divides its viewers into two radically opposed camps: one that views it as high art, the other on par with decorative art.

Cultivating or prioritizing a state of mind that is prior or antecedent to meaning is risky business, and not just in the visual arts but in life, especially if we are convinced that what vouchsafes our humanity is the uniquely human capacity of nomination, the assigning or affixing of names (concepts) to that which we find meaningful. Who would think of not naming a new born child?

Since abstract art aspires to the pre-ontological—a suspended state of wonder that characterizes the mind-set of the child—it could be argued that it shares the same mystical end-game as Zen’s no-mind, or transcendental Buddhism, or trance, or OM, or dervish ecstasy. They all speak to a common goal; the circumventing of the brain’s neo-cortical functions.

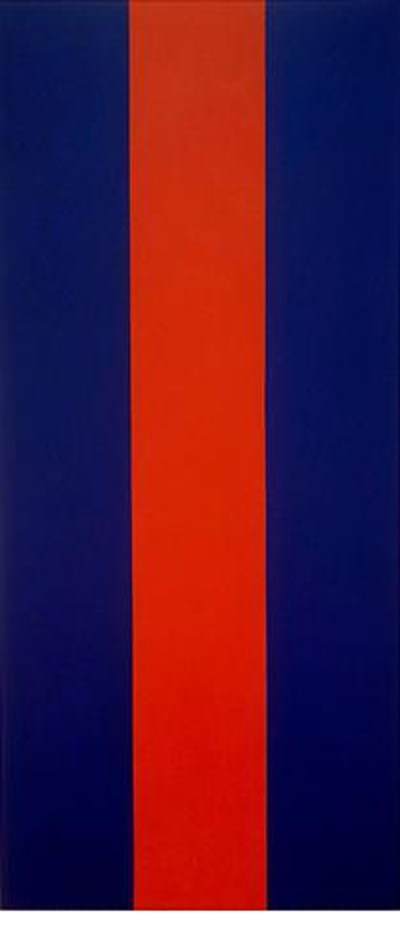

Could it be that we are attracted to abstract art like we are attracted to the drone in OM, or the mono-tonality in Rap, or anything or activity that facilitates the temporary shutting down of the mind? The music critic Jacob Siskind observed: “In a day when intellectual activity is looked upon with suspicion, something that reaches directly to the automatic nervous system and short-circuits the mind is certain to have an immediate response.” Et voila, Barnett Newman’s 3-striped Voice of Fire, (R), purchased by Canada’s National Gallery at a cost of 1.7 million.

Could it be that we are attracted to abstract art like we are attracted to the drone in OM, or the mono-tonality in Rap, or anything or activity that facilitates the temporary shutting down of the mind? The music critic Jacob Siskind observed: “In a day when intellectual activity is looked upon with suspicion, something that reaches directly to the automatic nervous system and short-circuits the mind is certain to have an immediate response.” Et voila, Barnett Newman’s 3-striped Voice of Fire, (R), purchased by Canada’s National Gallery at a cost of 1.7 million.

If abstract art expects to enjoy a broad consensus among its viewers, it must assume responsibility for the controversy it engenders and dedicate itself to articulating its goals how to get there. If its initial aim was to get real, to extricate itself from the prison of 3-dimensional painting which on a 2-dimensional canvas is illusory, it mistook that beginning for an end to the effect that far too many of its major players are confused and conflicted, and by extension, too many critics and curators.

Without a mission statement, without guidance and articulate leadership from the top down, works of dubious merit will continue to be exhibited while legitimate abstract art—and there are many instances of it out there—may never get its due. Until abstract art decides what it wants to be, it will be anything and everything that pleases the eye, and whether or not the affecting agency is a one-coloured canvas or a de Stael is moot since the effect is what matters.

In a private correspondence, an artist friend defending abstract art, explains:

If you cannot embrace art for art’s sake you are missing out on its quintessential essence. In your concern over the service to the farmer’s crop, you’re missing the beauty of the rain. If presented with ten paintings of an apple, what will determine which of the ten is best? Resemblance? No, what else then? And this is as unexplainable as abstract art. For every Leonardo or Raphael there were hundreds of third and fourth rate painters who painted similar themes. It has never been about content, but that ‘inexplicable otherness’ which makes the difference, a fact which to this day has yet to be grasped . . . abstract art has gone further than any other art form in clarifying this truth.

It could very well be that abstract art needn’t be anything more than the moveable feast of its marvelous first effects, that it need not have to explain itself to viewers like me who don’t get it, just as realism doesn’t have to explain itself because it is self-explanatory.

However, whatever position one takes, we can surely concur that it can’t be unwise to continue to question our most basic assumptions and resist the quick and efficient tyranny of absolute pronouncement, and with the view of holding abstract art to the highest standards, agree to defer to the judgment of time that in the long run tells for what is best and tolls for what is not.

__________________________________

Robert Lewis was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He has been publislhed in The Spectator. He is also a guitarist who composes in the Alt-Classical style. You can listen here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast