A Rolling Stone

by Geoffrey Clarfield (January 2023)

I had to come back to the tomb of Amran Ben Diwan in the town of Wazzan, here in the Riff Mountains of Northern Morocco because Moroccan Jews had written praise songs about this miracle working saint from the 18th century. The Moroccan Ministry of Culture had hired some Jewish Moroccan musicians to perform them at one of these interfaith festivals which now has branches across the country.

Visiting Israelis, curious European and North American tourists and French educated Moroccans showed up at these events as they seemed to signal that somehow, somewhere the “middle east conflict” (whatever that is) would one day be resolved so let us move the future to the present and act normally, now.

This time, my cook Zainab wanted to come and I had no objection. Esther from the embassy helped her get some European clothes and dressed her in a modest black dress, matching shoes and black headdress. She looked like a tourist from Sicily and blended right in.

The weather was fair, blue skies, a few clouds about 20 degrees centigrade and the sound system was bearable. The speeches were not. Everything was announced in French, Moroccan Arabic and the Berber language of the Rif Mountains which is indigenous to the area. The music went on for forty minutes and the speeches went on for twenty five, largely because now that most Moroccans are literate they still communicate as if they are not, so they speak as if they cannot read and write, as if the world depended on it. It certainly makes their literature worth reading, as they examine all and every aspect of the characters in their short stories and the details of their life.

Mohamed Talib’s short story, The Bus to Wazzan, demonstrates this style of expression.

Karima looked at her watch. It was two fifteen in the afternoon. She spent an entire minute watching the second hand trace out one full minute. She challenged herself to remember what she had done since she arrived at the bus stop. She had woken up. She had washed her face, changed her clothes, put on her jewelry, tied her turban, helped herself to a glass of cold tea from the pot from the night before, made sure her two children were still asleep and that her mother was in the room with them, cut herself some bread, put her purse in a safe place in her robe, latched the door and began walking to the bus stop.

One the way she counted five donkeys, three lorries, one camel and a wagon with a horse carrying ten children to the local primary school. She said a prayer to the local saint and hoped that the day would go well. But she was worried and she began to describe to herself all the things that could go wrong if she did not sell her wares at the market that day and make the necessary money to pay for the week’s expenses.

Although youngish and carrying herself with dignity she felt no different from the poorer peasant women coming in from the countryside weighted down with firewood that they hoped to sell to the local charcoal burners. The sun was getting hot and the taste of the olives from yesterday’s meal could still be felt inside her mouth, yet …

The next day I had a formal invitation to visit Bachir Attar and the Master Musicians of Jajouka. Where should I begin? Well, it all started out in the 1950s. Tangier was still a hotbed of decadent creativity for writers of at the time, unconventional romantic inclinations, and attracted writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William Boroughs and expatriate painters like the Canadian Brian Gyson. They had made contact with the musicians from a village in the Rif and had persuaded themselves that in the folk theater of the villages there were the remnants of a pre-Islamic ritual celebrating the God Pan.

Until the end of WWII much French and European anthropological scholarship had suggested that may of the unusual ritual practices and beliefs that clearly fell outside of Orthodox Islam must be the survivals of previous cultural layers both Christian, Jewish and Pagan. The Scandinavian anthropologist Edward Westermarck had made this observation based on years of fieldwork and writing about Morocco.

And it was not hard to notice that the proliferation of saints tombs and their worship all across Muslim and Jewish North Africa was fairly similar to the Punic Phoenician worship of local Gods, “Baalim” for those who read the Old Testament. These ideas are no longer in fashion. They are politically incorrect and often insulting to the host culture and its newly founded academic specialties in Moroccan universities.

Nevertheless there is something to it and the Jajouka story is an example of something curiously ethnographic entering the world of modern pop culture, rock and roll, and what is now called “World Music”. The Jewish presence in the Rif is truly ancient and until most Rifian Jews left Morocco their cultural impact was widespread. Here is how one travel writer describes it:

Of all the remnants of Jewish life in Morocco, Chefchaouen’s are the most visible. This city of steep steps and narrow winding streets is rinsed in blue, from its stucco walls to its weathered wooden doors. Conflicting stories say Chefchaouen’s Jews introduced the azure paint either upon arrival in the 15th century or in the 1930s while seeking refuge from Nazi persecution. Why blue? According to our guide, Yousef, it represents the sky, heaven and God’s ever-present power. He added, “Locals repaint the city blue before Ramadan every year, honoring the Jewish tradition.” The color is said to also repel mosquitoes and attract tourists (quite obviously from all the souvenir shops) …

Bachir Attar, the leader of the Master Musicians has a British wife and probably thought that he could augment his income when not touring around the world by opening himself up to tourists from Israel.

He told me:

There were many Jews in the area of our village. My grandfather told me all bout them. Some of them were very good musicians and singers and he once heard their songs from the synagogue and told my father they were no different than the songs of the Arabs.

And so, Zainab and I sat through their tourist spectacle. As it has been described by so many writers I prefer to quote just one to give the feel of this piece of recently commercialized folk ritual:

This music is part of its essence in a fertility ritual, a variant that has existed for millennia but is perhaps the best preserved in Jajouka. Similar traditions exist in all Mediterranean regions where masked and frantic characters, at certain times of the year, spread panic and fear among the villages. Some theories, notably that of the19th century Finnish anthropologist Edward Westermarck point out the similarities between these traditions and the Roman Lupercalia festival.

In Jajouka, the rites are centered on a character named Boujloud and on the woman he is in love with, Aisha. On the full moon, the musicians organize a festival during which this fabulous music is performed. It is characterized by a certain rhythm and melody and can be interpreted by many ensembles using different instruments such as ghayta and lira and even gambri and bendir. It can be performed at other times, at weddings and parties. Everyone can dance, but you have to look for the man with a hat and a goat’s skin … Boujloud tries angrily to hit the musicians and spectators with fertility branches, but he is controlled by the powerful force of trance music of the Jajouka players. Boujloud holds branches in his hands and, in his frenzy, he could hit anyone. The women struck by him will surely be fertile in the future and with them the whole fields and land.

Aisha l-Hamqa dances frenetically to seduce him and make him express more desire and produce more abundance and fertility. This extraordinary character fits Shakespeare’s Hamlet (26) who feigns madness: (Act 3, Scene 4) Polonius to Hamlet: “Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.”

And so this is what the tourist sees and hears, served with wonderful mint tea and local tagine. The whole experience costs one hundred Euros per person and I tipped them, as I like to support musicians.

During the performance Zainab was chatting way in Berber with one of the villagers and only stopped talking when the music was over. Bachir was all charm and gave me the now ritualized response of most Moroccans, “We were very sad when the Jews left Morocco. We do not know why they left and we welcome their return as tourists and temporary residents. We are brothers and sisters, sons and daughters of Abraham.” As the Beatles used to sing, “Yea yea yea!”

When Zainab and I walked back to the car she told me,

“Sidi. One of my distant relatives in the village told me that many years ago a musician from England had come to record the musicians of Jajouka and had asked him to post a letter. The musician spoke very little French and believed that the Englishman had asked him to “hold the letter.” He has held it for fifty years and finally decided to give it to me so that I can finally send it to its proper destination. He felt that he had held it in trust and that fifty years was more than enough to demonstrate his fidelity.”

Yes, I had heard that among non-literature Moroccans they perceived time differently. Things that had happened in the past, both real or imaginary, were often described as having happened just last year or “when my grandfather” was alive, and things that happened recently (like the war against the French in the 1950s) were somehow thought of as happening, long, long ago. Likewise, with the departure of the Jews of Morocco, since they left fifty years ago, some people talk as if they had packed up a century ago as there was no longer interaction at the rural level, where once almost every town and village had its Jewish quarter or Mellah.

I took the letter, put it in my briefcase and paid no further attention to the matter.

When we got back to my house in Tangier I took a shower, changed my clothes, drank the wonderful fresh tea that Zainab had made me and polished off a full loaf of round Berber bread that she had picked up from the local baker, spoiling myself and dipping it in fresh olive oil.

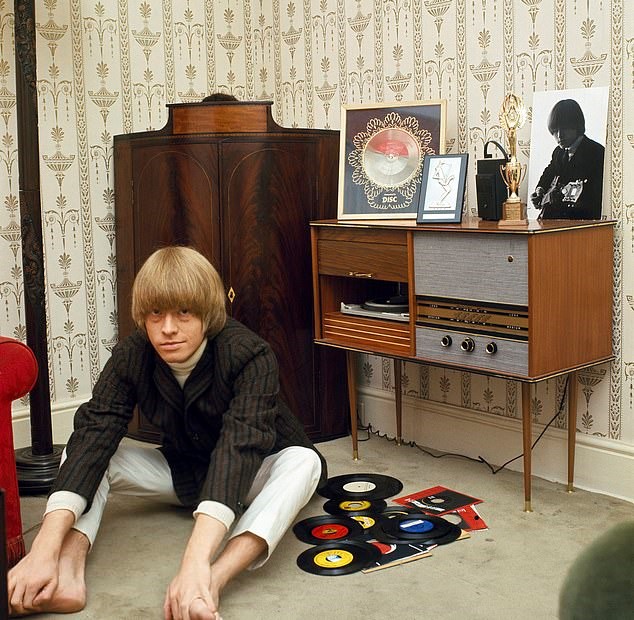

I picked up the letter and looked at it carefully. It was postmarked August 15, 1968. It was addressed to Mr. James Marshall Hendrix and the return address was for Mr B. Jones at the Hamzah Hotel in Tangier. I carefully steamed open the envelope as I did not want to tear a thing and read this epistle that is now part of the history of the discovery of Moroccan music by outsiders.

Dear Jimi:

I have been in Morocco for a good few months and I am feeling much better about myself. Mick and Keith are slowly trying to push me out of the Stones because I don’t write songs. All of a sudden, I am beginning to feel like George and Ringo who feel second class because John and Paul are hogging all the glory with their (admittedly) fine new songs. I thought that maybe some time spent down here would get my mind into a different groove and I believe I have been vindicated.

I fell in with musician and author Paul Bowles who has introduced me to the musicians of the village Jajouka up here in the Rif. They smoke a lot of kif and I have given up drinking and anything else and join them at their pipes. It makes them mellow and does the same to me although I still feel persecuted by the demon of my disapproving father. It does not matter that I am famous—making tons of money. He just thinks rock and roll is disreputable—you know the devil’s music.

Well ha ha ha. Here in Morocco people believe in all sorts of spirits and there are these black African Moroccans called the Gnawi, who regularly exorcise people possessed by these genies. I sympathize with them as being here in Morocco seems to be exorcising my own demons. I do not feel as stressed as in London. I don’t have to deal with Mick’s and Keith’s incessant emotional put downs and I do not react by taking all and anything anyone gives me to smoke or snort or swallow. I am going to release an album of these Jajouka musicians. I am sure it is going to be a hit. It will put Mick and Keith in their place and our unbearable manager, Andrew.

I imagine going on tour with them and as I know you are coming to spend a vacation on the Atlantic Coastal town of Essawira, it would be nice if, let us say, we could meet up in Marrakesh, hang out with the Gnawi, jam and record and maybe even do a benefit concert for the numerous street kids of the old city who seem to live off thin air.

I suspect that the Gnawi have a similar tradition to the blues men who for all I know may be descendants of the griots, the minstrels of West Africa. Maybe you’re the descendant of one of them. As the locals say “it is written” that we take this path together as I do not know how long the Stones (which I started and invented) are going to keep me. Who knows, we may end up going local and exorcising the spirits of disturbed Western tourists and expats who seem to be swarming here.

By the way, Bowles did a survey of traditional Moroccan music in ’59. He recorded 250 songs in about twenty different venues of Morocco. I’ve listened to all of them. Clapton and you must come here and hear them. You never know. Rock and roll may soon die and you and I could become a folk song collector and professor of music.

My headmaster always said that I could have gone up to Oxford or Cambridge had it not been for my addiction to the music of Blues Master Robert Johnson. I am coming to the conclusion that Johnson was descended from Griots, a musician from west Africa and that the Gnawi are the source of the blues.

I think we have come full circle you and I. Not much more to say.

In friendship,

Brian

I was stunned. Here was a letter from rock star Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones to his best friend African American blues master Jimi Hendrix, suggesting that they could make a career out of what later came to be called “World Music.” Who knows what might have happened? The history of modern music could have been very, very different. Upon reflection I concluded, sadly, that the problem was that both of them would be dead at 27 and so that super group idea died with them.

I shared my story with my Ambassador and he told me how to proceed.

I then wrote an email to the cultural attaché of the British Embassy in Rabat, who had once been a young rocker at Oxford and who had played in Tony Blair’s rock band. It read:

From the Office of the Israeli Cultural Attache to the Kingdom of Morocco

Dear Clive:

Remember those post cards from the French front during WWI that somehow got delivered to England in the 1970s? Well, I have come across something similar and my government would like to donate it to your government …

Table of Contents

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast