Norfolk Island

by Lawrence Winkler (March 2025)

Come out mine I show you foot dem callet God’s Country, hengen up een myse kitchen. —Merv Buffett

Most departure lounges smell of freedom. This one was more complicated.

‘Why would you want to go there?’ Our Kiwi relatives had asked. ‘Unless you’re newlywed or nearly dead.’

‘Maybe I’ll win some money at cards.’ I said. We bought four bottles of wine and one of rum in Duty Free, and found a long row of bored prospective passengers, for the NZ794 weekly flight from Auckland. The geriatric gathering they warned us about was there in such profusion, I bet Robyn that so many more would be boarding than arriving, and so much more leg room would become available, that we would be able to stretch out in ever increasing comfort, as the flight progressed.

I read the immigration form. Do you have any criminal convictions, or have you been deported or removed from any country? And I wondered. Are these criteria for exclusion, or entry?

We dropped down over a volcanic landscape softened to rolling green hills by time, and tribulation.

An overhead voice announced our imminent landing, but its owner wasn’t quite as switched on.

‘If you are connecting to a domestic flight…’ She said, before taking it back. A lot happened on the Southern Sea, but not as much as what happened after landfall. There was nowhere else to go from here, and in the old days on this island, domestic flight would have gotten you shot.

Robyn and I filed off the plane, into the terminal.

The immigration guy wasn’t sure what to do with me. I had an entry permit from some agent profiteer, the validity of which had been confirmed by the Australian government. No one had had told the Norf’ker perusing my passport. He was conflicted about my legitimacy.

‘You’ve let in worse.’ I said. He scowled, but his stamp fell hard. Welcam tu Norfuk Ailen.

We had landed on a subtropical oasis, three tranquil miles by five, home to eighteen hundred natives of the most unusual pedigree.

‘It looks even more beautiful than the photos.’ Said Robyn, before we landed. It did.

We emerged to find the proprietor of our cottage, standing under a one-acre Banyan tree.

‘G’day.’ He said. Wayne was a former Kiwi car salesman from Tauranaga, who’d married a local girl. He was unimpressed with the work ethic of the Islanders, but even less ‘dazzled’ by the Australians.

‘They’re the ones drinking.’ He said. ‘Aussies, mozzies, same damn thing.’ But Norfolk was also reminiscent of rural Australia in the 1960s, especially those trees, which grew up in small town parks all over the country, with predictable regularity.

Wayne drove us into the only town of Burnt Pine, and a short diversion to the Farmer’s Market. Under the flame trees, a handful of stalls sold giant papayas, bananas, kumara, peaches, guavas, cauliflower, winter squash, guava jam, and roast pork smoked over pinewood.

On returning, he pointed to an old silver Mazda and handed over a set of keys. The license plate had four digits.

‘Here’s your car.’ He said. ‘I’ll give you a brief tour. Follow me.’ Robyn asked about road rules. He laughed.

‘This is the only place in the world where the cattle are outside of the enclosures. Driveway cattle grids are to keep them out. Cows have right of way, and the fine for killing one with your car is about five hundred dollars. They’re our watchdogs. The fencing is made from recycled Marsden matting, used to construct the runway during the war. Our potholes are huge because we ran out of tar. Petrol is $2.50 per litre. Seatbelts are optional. We have one roundabout and one streetlight. Everyone waves at passing drivers. The safest place to leave your car keys is in your car. Any questions?’ We had no questions.

‘I’ll point out the shortcuts.’ He said, and was gone over the first hill, almost before Robyn had found the gearbox. Hundreds of swallows lined the hydro wires. We caught up to Wayne and watched as he motioned right, then left, then right, and we took it too soon.

Robyn tooted the horn at some cows in the road, dodging chickens and potholes. ‘Why haven’t they considered filling these things with cowpies? We stopped at a parking spot on Mission Road. Each space was spoken for. Prison Wardens … Glass Blowers … Nose Pickers …Corrupt Politicians … Yogi Bears … Plant Lovers …Horse and Carriage … Tandems … Mopeds … Surfboards … Skateboards … Broomsticks … Faeries.

‘These people are a little different.’ I said, as Wayne finally caught up with us, flailing his arms. We flailed back.

Up to the left of Bullocks Hut Road, Wayne led us into a bucolic setting next to the National Park. The garden was full of orange and grapefruit trees, and palms, with ‘choir boy’ tin collars around their trunks, cartoon crimson rosellas and local green parakeets darted in and out of the forest, strafing the English blackbirds on the lawn.

‘Restorative justice.’ I said.

‘Welcome to Anson Bay Lodge.’ Wayne guided us to our cottage. ‘Anson Bay is over the hill, named after the famous admiral, the one that introduced rum rations to the Royal Navy.’ I offered Wayne a rum.

‘Wet with Anson’s tear?’ He said. ‘Bit early.’ And he wished us a Merry Christmas and goodbye.

‘No need to lock it.’ He said. Robyn and I opened the open door to the cottage, and a blowfly flew out, liberated from incarceration. I wondered why there was a coat rack over the mirror. The temperamental Telefunken television improved with an aerial, fashioned from aluminum foil, but it took some time to figure out that the channels would only change by pressing the volume buttons.

Robyn put the jug on, and I checked my messages.

‘Someone recently tried to use an application to sign in to your mail. We prevented the attempt in case this was a hijacker trying to access your account.’

Even the ATM I had accessed, up town was suspect. You no got nuff money in dees account.

‘We’ll need wettles.’ Said Robyn. It was coming on Christmas fast, and we drove back up town, for victuals. The first surprise at the supermarket was how normal it appeared. There were rows of this and that, with aisles that were not quite empty. The second surprise was what kind of this and that there was and wasn’t. Tinned goods from the Antipodes were in good supply, as was long-life UHT milk, cheaper to import than to pasteurize the real stuff locally. There was no dairy industry on the island. Even though the roads were full of cattle, over sixty per cent of the beef, most of the chicken, and all the lamb, was still imported. Island feral chickens were tough enough to bounce off the kitchen floor, and Norfolk sheep had foot rot. The signs over the butchers were banal. Please don’t prick our sausages … A steak a day keeps the doctor away.

Norfolk has no working harbour. Two piers, at either end of the island, are the only means of bringing in freight, and which landing to use must be decided on the day of arrival. Cargo is loaded onto smaller craft and brought to shore in military-style maneuvers, against a four-knot current. Such tricky logistics, coupled with strict quarantine regulations, means that little fresh produce, except potatoes, onions, ginger, and garlic, can be imported. The crops that can be grown above the steep escarpments, citrus, bananas, guavas, kumera, cauliflowers and winter squash, only last so long. Peaches are available for two weeks.

The climate is too cold for coconuts. Guavas grow wild and make excellent preserves. American whalers introduced Thanksgiving, turkeys and pumpkin pie, and cornbread, and the British convict system introduced the wind and water and manpower methods to grind the corn.

But it wasn’t Thanksgiving; it was Christmas, and most everything that had been on the supermarket shelves was now there in spirit only. Someone had stolen every mincemeat manifest morsel but the music. There was no bread and no fresh vegetables. And what was left was the third surprise. The prices were in scientific notation.

‘It’s hard to believe how much money I earned last year.’ I said, ‘And here I am on the worst convict island in the South Pacific looking for the cheapest soup mix.’ An Aussie mainlander shopper had overhead my comment and hove to my starboard side.

‘You should try living here.’ She said. ‘The eggman will be giving away free cartons of eggs at the P&R in a few days.’ Robyn and I got directions.

Between the Huggies nappies and the Wondersoft, we managed to cobble together a Yule basket.

‘Here for the holidays?’ Asked the checkout girl. It appeared so, and we inquired if she knew a good place for lunch.

‘Dino’s at Bumboras is good.’ She said.

About fifteen minutes from up town, we drove over a set of cattle-dissuading judder bars, to a venerable crumbling tin-roofed homestead with palms and pines, and lovely gardens. Old straw Pitcairn hats lined the dark interior timbered hallway. The restaurant was empty, except for the owner, Helen, who inquired about our intentions.

‘Lunch.’ I said, and she showed us to a sunlit table with a rich red tablecloth, set with Georgian glassware and silver flatware and contorted crockery. The artwork on the wall was a little off the wall. Robyn had the seafood linguine, and I ordered a T-bone with rosemary potatoes. Helen dropped the steak cutlery in a parabola, and a near miss, over my shoulder.

‘You could have had a knife in your back, mate.’ She said.

‘Isn’t it an old tradition here?’ I asked. It would be the best meal of our visit. I put a plastic card in a machine in a place where, unlike every other machine there that had represented a form of torture, I had legitimacy. Helen told us to drive further south, to the Bumbora reserve.

Tangerine and blue rosellas screamed around our arrival, before blasting apart down the path through the trees. Magnificent trees. Trees with textured bark and breadth of pachyderm proportion, ponderous pillars of elephant trunk rising into the sky, throwing off green-fingered triangular fans of coniferous confidence, separate and sideways. Their shallow roots went as wide as the trees were tall.

‘Cook thought that he had found the mother lode source of ship’s masts.’ I said. ‘But they have too many knots to make good spars. Norfolk pines soak up salt, so the locals never park under them. The original convicts planted a tremendous ‘Avenue of Pines’ windbreak, containing a giant old ‘Tree of Knowledge.’ The Americans cut them all down to construct an airfield during the war. They removed 26 homes and 240 islanders, used bulldozers to knock the tops off several hills, and filled the valleys with hilltops and Marsden matting mesh. It was never used it as a major base.

We identified the four remaining rare endemic Norfolk Island euphorbia, among the white oak or Norfolk Island hibiscus with its bright pink flowers and yellow stamens. Large land snails were big enough for escargots. There were patches of taro, and trees of white paperbark, black peppered with spots. The path became a boardwalk, zigzagging down to the silver surf in the bottom of an amphitheatre of tall pines soaring stratospheric out of a cliff of grazed lawn, like the final green on God’s golf course. Big, scattered piles of gray rocks protruded out from a white sand beach into some of the clearest seawater in the Southern Sea. A colony of breeding white terns perched off to the left. Clouds rolled over the sun and dropped rain, and then retreated, before returning to repeat the performance.

‘It’s the kind of climate that can’t decide what it wants to be when it grows up.’ Said Robyn. But it became more a more decisive drizzle as we headed back towards the lodge.

The Botanical Garden was up Grassy Road, along moss-covered fence posts and through the cows and the potholes. Drizzle and mist turned the light suffusing through the canopy a glistening green, and our trip ina stik became primordial. Before European colonization, before the clearing and the grazing and the weeds, Norfolk Island had covered with subtropical Araucaria rain forest of 174 native plants, a third of them found nowhere else on earth. Robyn and I walked under the tallest tree ferns in the world, in an understory thick with lianas and broadleaves, undulating over the forest floor. We weaved around contorted open vines and wrapped vines, green berry clusters, tiny yellow and orange orchids, barks of various textures and colors, and a large carved punga tiki. There had been only one native mammal on Norfolk Island, Gould’s Wattled Bat, now extinct. But the tin ‘choirboy collars’ around the palms gave a hint of what the colonists had brought along for the ride. I had asked Wayne what they were for, back at the lodge.

‘Fate didn’t arrive here like an eagle.’ He said. ‘It crawled off with the rats.

***

‘Noisy bastards.’ I said, waking to the larrikan rosellas, boomeranging around their Norfolk parakeet cousins. Robyn was already brewing the coffee.

‘We need to get up anyway.’ She said. It was the day before Christmas. ‘to beat the other noisy Aussies to the bread shop.’

The Mazda was already moving when I shut the passenger door, and Robyn headed off up town. We stopped for a brief look at Puppy’s Point, a lone Norfolk pine coupled to a sheer coastal cliff over 200 feet high, sloping down to the Pacific foam, raging below. Cattle chewed in time to the view. A little further along, an honesty box sat outside the entrance to Strawberry Fields maze. Admission $7.

‘This is a convict island.’ I said. ‘You think they’d charge you to get out.’

‘Nothing to get hungabout.’ Said Robyn.

Saunder’s Meat-Foodstuffs-Electrical was closed, and so was the supermarket, but we got our loaf at the P&R.

‘Did you pay for the bread?’ Asked the proprietress, as we were leaving.

‘On the counter.’ I shouted back. It wasn’t as if there was anywhere, we could have escaped to. We left our prize in the trunk of the Mazda and went walkabout.

The rest of Burnt Pine was still asleep, except for the golden silk orb-weaver spiders and the gossamer they danced on, shimmering in the rising sun, a gilded cage for the unsuspecting. Fishermen on other coasts of the Indopacific had formed the webs into a ball, and thrown them into the ocean where, unfolding, they would catch their bait fish.

We passed through the closed commercial heart of town. Tahitian Fish … Bounty Centre Shop … Four Corners … Pigs Can Fly $$$. A plastered Santa posed in a red and white suit without a hat in a display window next to a provocative female mannequin with a short satin bathrobe and a tennis visor over her eyes. We walked by the Anson Coffee Club. The only place for a cup of coffee—closed until further notice.

Robyn put a red hibiscus behind her ear, and I took a photo of her standing under a gigantic spreading dracaena, a fountain of leaves engorged with venous blood.

Ships masts from New England would soon become unavailable, with the opening shots of the American War of Independence. Also, all the flax that the Royal Navy required to make sailcloth came from Russia. When Catherine the Great restricted its sale to Britain twelve years later, the English were desperate to find another source. New Zealand flax at source was impossible to get because of the bellicosity of the Maoris, but Norfolk was uninhabited and planned for ‘dual colonization’ with Botany Bay.’

I had read about the three phases of Norfolk settlement—the First Convict Settlement from 1788, abandoned in 1814; the ‘planned hell’ of the Second Convict Settlement, from 1825 to 1855; and the 1856 relocation of the entire population of Pitcairn Island.

The First Settlement began with six women convicts ‘whose characters stood fairest’ (and whose fair feet hadn’t even touched the ground in Australia), nine male convicts, and eight free men, ‘the best of a bad lot.’ The H.M.S. Supply made the thousand-mile journey from Botany Bay, in a race to beat the French, but La Perouse had already been and described it as a place fit only for ‘angels and eagles.’

The British commandant, Philip Gidley King, had similar misgivings but unlike the French, he had no choice and, after spending five days sailing around the island’s 300-foot-high cliffs, forced a landfall on the ‘huge rainforest.’ King wasted no time trying to turn the island into a garden, to feed the struggling barren settlement back in Australia. He meted out flogging punishments for stealing rum, forbade the building of any boat longer than twenty feet, and took himself a mistress. In only a matter of months, his convicts had cleared ground, constructed a road from the landing place to Anson Bay via Mount Pitt, located sources of limestone, and fathered the settlement’s first son, which he named ‘Norfolk.’ By April of 1789, he had food crops in the ground—groves of Rio bananas, orange trees, sugar cane, wheat and barley and rice, squash, potatoes, artichokes, turnips, onions, leeks, lettuce, parsley, and celery. But as far north as they had come, it was all about to go back south.

The pines were not resilient enough to make good masts. Because none of the settlers had the necessary skills to prepare the flax for manufacturing, two Maoris, Woodoo and Tookee, were kidnapped onto and off the H.M.S. Daedelus, the first record of blackbirding in Southern Sea history. But flax weaving was considered women’s work, and the Maori men had no idea or interest in what to do. The crops failed due to the salty wind and caterpillars and the rats. The absence of a decent harbour hindered supply and communication. A convict insurrection in 1789, the same year as a synchronistic mutiny half an ocean away, was almost the end of the First Settlement. But it was not far off.

On 19 March 1790, the H.M.S. Sirius, sent from Sydney to relieve the colony, was shipwrecked on the foreshore, and marooned for a year until rescued back to England. Three years later, the decision was taken to abandon Norfolk. A small party remained to slaughter the stock and destroy all the buildings until the final remnants were removed in 1813. For another dozen years, the only visitors would be the whalers.

Robyn and I drove to the abandoned whaling ‘factory’ on Cascade Bay, where 26,000 whales had been killed, the last one in 1962. Here were convict cooking pots and whale vertebrae used for milking stools, and a heartbreaking story of a whale cow giving birth to her calf, while being sliced into pieces on the deck ramp. The smell of burning rubbish was thick in our throats.

Past a kentia palm plantation, we drove to the perfection of St. Barnabas Chapel. Founded by Bishop John Coleridge Patteson, five years before his habit of coming ashore off his Southern Cross wearing only a top hat, got him speared and eaten in the Solomons, the St. Barnabas training college brought in 200 ‘students’ from all parts of Melanesia, for whatever abuses would occur. The chapel, though small, had tiled marble floors, Solomon Island mother-of-pearl inlaid, carved pews, and the most beautiful red and green rose stained-glass windows, one by William Morris, and the other by Edward Burne-Jones. The kauri and Norfolk Island pine open timbered ceiling was built in the shape of an inverted boat and stained with whale oil. We sang a hymn, in honor of the acoustics.

We stopped for tea and scones with jam and cream at an estate. We sat among large whaling pots converted into planters, in a magnificent pruned garden of palms and bromeliads and staghorn ferns and all other manner of other tropical verdure.

Robyn and I headed back to Anson Bay Lodge, via the honesty jar in the roadside kiosk at Barnaby’s Fresh Fruit & Veg. The cows surrounded us, as we picked out our wettles, from the courgettes, lemons, onions, beans, Roma tomatoes, passion fruit, and winter squash on the pine boards. ‘Twas the night before Christmas. A bubuck owl hooted at the full moon, calling back the whales.

***

Our cottage at Anson Bay Lodge abutted hard up against the national park, and the distinct probability of being clipped by a low-flying parrot, unless you kept your head down. On the morning of the third day, Robyn and I decided to drive the upward spiral around to the other side, and the summit of Mount Pitt. The views out to the Southern Sea took their own breaths between the occasional open breaks into vertigo. Norfolk pine tops fell behind the sky in a path of evergreen Christmas shooting stars, melting into a receding mist. A congregation of tan and yellow and black and white Norfolk Golden Whistlers gathered on the branches around her.

A stray grey Tamey joined them in a chatter of chirpy whistles, going up at the end of their sentences.

‘Sound like Aussies.’ Robyn said.

‘They’re also called Thickheads.’ I said, with an epiphanic nod. ‘This is the only place on Earth to find them and, with the black rats and feral cats finding them as well, there may soon not be many left to find.’

‘They shouldn’t be so friendly.’ She said.

Back at the cottage, Robyn loaded a picnic basket with leftover chicken, a salad assembled from the purchases of Barnaby’s honesty box, and one of our bottles of Kiwi sauvblanc. Packed in the boot, we drove it out, via a northern tour to Fisherman’s Lane past the grey moss-covered south-facing fence posts, and a yellow, blue, grey and red-faced wooden fish carving, on our way to Anson Bay, for a Christmas lunch. We arrived at the top of the reserve and looked down over and onto and into a deep crescent of pale blue sky becoming beautiful cobalt horizon becoming turquoise bay becoming broad eggbeater waves becoming sugar sand shore.

‘Should we hike down first or have lunch first?’ Asked Robyn, knowing immediately after she asked, what the right answer was. ‘Lunch.’

We found a picnic table under one of the white oaks between two Norfolk pines and laid out our spread. The only other person in the reserve was dressed in overalls and a cap, wearing sunglasses and sub-dermal ink, and trans-dermal metal. He wandered over to chat.

Darren was a painter and a mushroom grower but wasn’t making much of a go of it.

‘It’s all the rules, mate.’ He said. I asked him if the island hadn’t been built out of rocks, and rules. Darren told us he was an Islander, and resentful of the increasing invasive ‘Mainlanders’ that were ruining his paradise.

‘They’re like that Kikuyu grass there.’ He said. ‘Bullies.

What have they brought us? Canberra gave us four million dollars, about what they’d spend in a year on fireworks. They’ve brought us crime. There hasn’t been a murder on the island since 1893, and we had two in four years. In 2002, someone murdered Janelle Patton. The killer ran her over with his car, fractured her skull, and stabbed her 64 times, before pulling down her panties, and dumping her in the Cockpit waterfall reserve over there. The Aussie cops ran around with no guns in their holsters and announced that they were going to test the DNA of everyone on the island, including our religious elders, before they found the Kiwi chef who did it. The Aussies are the bad drivers and the petty thieves. Before they came here was never any crime on Norfolk.’ I must have been staring.

‘Well, not for a long while, anyway.’ He said. ‘Look, the Aussies can come here and live anytime they want, and there’s more and more of them doing that. If I want to go to Australia, I need an Australian passport. And what do want from us? They want to impose an income tax. We already pay higher freight charges than anywhere else in the world. You’ve been in the supermarket. Milk is seven bucks a litre. A kilo of yogurt is almost twenty dollars. We’ve got oil and gas offshore. You don’t think they know that? That’s the reason why they want to turn our legislature into a local council and send our self-government down the gurgler. It’s breaking the hearts of the old people.’

‘We’re Pitcairners.’ He said. ‘In 1856, Queen Victoria gave us this land. Every year we celebrate Bounty Day. Our national anthem is God Save the Queen, not bloody Advance Australia Fair. Norfolk is our homeland. If less than two thousand people can manage our own customs service, schools, stamps, phones, and rubbish, we can go the rest of it alone. We’re mutineers mate. We know how to deal with them.’ Darren shook our hands, and wished us a merry Christmas, and a happy time on the island. We wished him the same and finished our picnic lunch.

The adjacent grassy track switchbacks would bring us down three hundred feet of steep coastal cliffs onto the outstanding sand beach seascape of Anson Bay. Robyn and I walked through wind-pruned white oak and native flax, moo-oo and coastal lily, and porpieh and shade tree and a single euphorbia. African olive and Hawaiian holly and lantana had invaded, long before the Australians. There were weird miniature purple corncob candelabras, with tiny symmetrical pink flowers around the top, and the inverted parasolic profiles of Norfolk evergreen branches, against the upper atmosphere. We passed under high vertical crenulated columnar cliffs of basalt lava, pale yellow and purple and red layers of volcanic ash and scoria, eroded and threatening to slide down on top of us. Fallen rocks flowed down grey to become cream sand, and the Norfolk Island beans and native vignas in the dunes below. Robyn ran ahead, and had the empty wide beach all to herself, except for the blue bottle jellyfish, and the sign. Strong current- can be dangerous to swimmers.

White terns and the rarest of red-tailed tropicbirds hovered overhead, or plunged dived beside us, likely the reason why I found one of his thin red tail feathers on the sand. We sat and played with the curled calcium castings of long-departed marine worms and danced with each other’s deep footprints in the sand, until one of the deep footprints decided to dance back. The hornet that stung my left foot was trying for the third murder on Norfolk since 1893, but I managed to hobble back up to the top of the reserve, without giving him the satisfaction.

Robyn and I were looking forward to our Christmas dinner at the South Pacific resort that evening.

We arrived at an abominable assembly of ancient Aussie males wrapped around young Oriental girls, or horrible old Antipodean couplings, wearing too much perfume, but not enough to disguise the miasma of death.

‘Bring me a gin!’ resonated through the lobby, as a layered stack of plastic chairs rolled off into the swimming pool in slow motion. Aussies poured from paper bags from under tables, everywhere. Whatever young people were in attendance, had either skirts that didn’t cover the bits that should have been covered or fabric tension that should have never been, accentuated things more discreet. Inside the dining room, some attempt had been made at celebratory decoration. Lime green nylon bows and wreaths had been draped over black velour chairs, lining pink tablecloths on which decade-old ‘Best By’ crackers and Cadbury’s products had been formed into centerpieces. Balloons floated across the ceiling, and spherical white paper Japanese lanterns stole light from the food.

We got called to the buffet. The prawns were so salty, they must have come from another age. The back of the pig was so flayed, that he could have started a religion. I asked for a turkey leg and was admonished for being ‘too selfish.’ I came back to get the other leg. The mayo was off. The Filipino servers ran out of chowder unless you spoke a little Talagog. If you did, you could get them to turn the lights up or down. We figured out how to get more than one free glass of bad wine, from several pourers, by pouring on our own charm. ‘Puffy,’ A slicked-hair relic from another time and place named ‘Puffy,’ played old Elvis tunes and Neil Diamond on a boom box, providing us with an overwhelming urge to slit our wrists. Robyn and I left early, to save ourselves.

‘Is there a fine if we don’t wear our seatbelts?’ I asked. Robyn was prosaic.

‘They’ll throw you in jail.’ She said. ‘But the food, the food will be better.’

***

Boxing Day. I traded the French picnic basket from the lodge shed, for the snorkeling gear. First in, first served.

‘Do you think it’ll be safe to leave it in the car?’ Asked Robyn.

‘They’d flog anyone trying to steal it.’ I said.

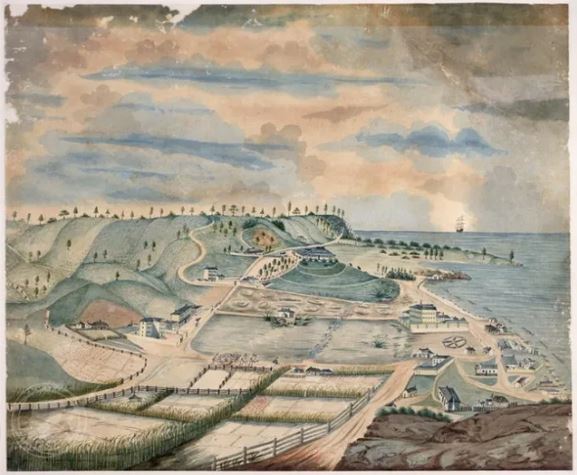

Burnt Pine had flat-lined overnight, and we drove through it, climbing up to the viewpoint on Rooty Hill Road, for an early morning aerial view of Kingston.

‘So this is where.’ Said Robyn.

‘This is where.’ I said.

But what first caught our eye were not the remains of the Second Settlement, on the beach below, but the barren hairdryer-shaped reddish brown offshore island, nozzle pointing to Pitcairn, almost four thousand miles away. Wayne had told us of the only remaining life on the island, carnivorous rabbits, eating each other’s lucky hind feet. How late it had become.

Our view came ashore to the roof parapet rosellas and rich ochre stone walls of the Georgian row houses and military barracks, and prison, below.

‘If you were bad you ended up in Botany Bay. I said. ‘If you were bad in Botany Bay, you ended up in Tasmania; if you were bad in Tasmania, you ended up here.’

‘And if you were bad here?’ Robyn asked.

‘You still ended up here.’ I said.

In 1824, the British government sent instructions for NSW governor, Thomas Brisbane, to recolonize Norfolk Island. They had designed the station for the ‘worst of the worst,’ the ‘lees and dregs of mankind,’ criminal lunatics, half-crazed, warped and perverted in mind and body, brutes of low mentality, or rotten with every vice produced by the degraded instincts of the worst types of sub-human beings.

Its construction would not only create an impression but give birth to a myth.

Norfolk would become the ne plus ultra of convict degradation, a great Hulk or Penitentiary for the incarceration of reconvicted incorrigibles, a place of the severest punishment short of death, a Hell in Paradise. Reformation was not a goal.

Of the 6500 convicts that would be transported into the ‘machine for extinguishing hope,’ over the thirty years of the Second Settlement, only a minority would be as bad as advertised. Less than half had been the ‘doubly convicted’ perpetrators of more crimes committed since arriving in New South Wales. Seventy percent of original offences were non-violent crimes against property, the burglars and pickpockets and highwaymen who stole cheeses and ducks and shawls and watches and handkerchiefs and livestock, or the clerks and embezzlers and forgers and fraudsters and utterers of more ‘gentlemanly’ crimes. There were rapists and gang rapists and arsonists and murderers, but fewer than 4 percent had been transported for violent offences, the same proportion that were under the age of fifteen. Most had been farm labourers, and the average sentence had been three years, a far cry from forever.

Far more cries were in their Orwellian future, inhuman boots forever stamping on human faces.

From the moment of landing, discipline was abusively enforced. Military guards never walked alone. Almost two hundred cubic yards of earth was moved by hand, to reclaim the swamp’s ‘slow-motion water’ on Slaughter Bay. Kingston arose, one stone wall at a time, into a ‘miasma of sin, where horror and vice beyond sane imaginings grew like poisonous fungus on a dung heap…a place of perverted values where evil was reckoned to be good and where the unbelievable became the norm.’

By the mid-nineteenth century, Norfolk was the most notorious penal station in the English-speaking world and represented all that was evil about the convict system. One of the most sadistic commandants was James Morrisset who, during his five-year reign of terror, ‘delighted in applying the lash in person.’

In January of 1834, the prisoners rebelled, planning to capture Morisset and ‘cut him into four pieces to be divided about the island.’ It didn’t work. The mutineers were captured and tried.

Father William Ullathorne, the Vicar General of Sydney, arrived to comfort those convicts due for execution.

The bishop was to learn of the existence of ‘suicide lotteries,’ and the murders, performed ‘without malice and with very little excitement,’ that could get a man hanged who wanted to be, if he found it easier to kill another than himself.

In all, before the end of the Second Settlement, eight-six prisoners would be hanged and three thousand would take their own lives.

Not all the commandants were as brutal, of course. Alex Maconochie’s four years in the early 1840s were an enlightened experiment in penal reform, for the place and the age. But Maconachie was replaced by Major Joseph Childs, a strict disciplinarian. His wife wrote of the later Mutiny of 1846.

Four officials were murdered, Childs was fired, and thirteen convicts were immediately hung by his heir, a monocled monster named John Price, ‘privileged, amoral and ruthlessly contemptuous of human suffering.’ A visiting magistrate later exposed his horrifying tortures and incessant flogging, overseer corruption, and inadequacy of the prison’s housing and food.

In 1854, the colony was totally abandoned, and its convicts transported to Van Diemen’s land, to finish their lives in the town founded by the old, exiled exiles from the First Settlement. They had called it New Norfolk.

Robyn and I took a deep breath, and drove down the hill, to the ne plus ultra of Hell in Paradise. We landed in the middle of a festival. There was a live band and a surfing competition, and sausages and ice cream, and medieval tents and banners flying in the wind.

‘I can’t understand why the prisoners didn’t like it here.’ I said. ‘It’s such a beautiful spot.’ The Georgian box buildings had less ochre now, Monopoly pieces of lemon and pink pastel-painted stuccoed squares and concrete cylinders and equilateral triangles, covered in hipped slate or shingle, or having no roof at all. Tall chimneys soared out of both edges of each edifice. Old dories lay about, one dripping and oozing wide rust down otherwise white panels, one flattened out into the ground, like it had melted into the lawn growing up through its bulkhead. The column-flanked gray Palladian entry to the yellow-cream Royal Engineer Office A.D. 1851, still looked open for business, but it wasn’t. Neither was the stone carcass of the Crank Mill, although you could feel the agony in the limbs of the convict teams, shifting the heavy grindstone capstans, the suffering sounds of which could be heard back in Anson Bay. What was open was the rock relic workshop of the tattooed Aussie shingle-makers, seated and surrounded by stacks of Eucalyptus shakes and whittling piles.

‘I do it ‘cause I like the smell.’ One said, swinging his maul into a fresh plank.

‘I do it for the money.’ Said the other, a little slower.

Robyn and I walked around the walls of the penitentiary, trying to absorb the size of what had happened here. I got nothing from the vast expanse of walls and what was left standing of the beveled block buildings, until I honed into the ruin and rubble tilted footprint of the pentagonal congested cellblocks, and the one lower corner of each of them that drained off the dysenteric feces and calcium concreted urine, of the ‘lees and dregs of mankind.’ We left them for the Commissariat Store, in the basement of the Pitcairner’s All Saints Church, and the glass beads and ceramic pieces from the First Settlement and the whips, leg irons and crankwheels from the Second. The attendant was a brusque, ruddy-faced shorthaired Aussie matron, who insisted we buy the entire museum package and was unimpressed with the hypercritical alacrity we employed to navigate the displays. A friendlier face greeted us at the former Protestant chapel, in the H.M.S. Sirius Museum. She admitted to beginning her job, but let us have the run of the place, to play with its ill-fated Jeremy Benthamoid masthead, and black-painted rescued knobbled iron anchor.

But it was back to the Pier Store Museum for what had been billed as a ‘Tagalong Tour,’ offered by a resident archeologist with a resident expert on the Second Settlement.

‘Helen should be here any minute.’ Said the attendant. ‘She’s very knowledgeable.’ And in walked Grumpy.

‘Who’s for the tour?’ She asked. Robyn and I and some others put up our hands.

We moved through the main floor of the exhibits. She showed us the original bell from the H.M.S. Bounty, and other relics from Pitcairn Island. Her tour went on to places we had already been, and we lingered behind upstairs, to take in a video of Norfolk history, on the Telefunken television. To watch the DVD, please call the museum attendant for assistance (there is a trick to getting it started). The attendant came upstairs.

‘You change the channels with the volume buttons.’ She said.

‘Like our other one at Anson Bay Lodge.’ Said Robyn. And we learned about the four mutineers drowned in Pandora’s Box, the Codex Pitcairniensis, how the Melanesian Mission had created Pitcairner resentment by commandeering an eighth of their land, how the ship they built for transporting goods to remote markets, the AV Resolution, was impounded in Auckland for being unable to pay port duties and ended up in Vila harbor, and how the US airstrip generators replaced the whale oil lamps in 1945, and how the grid is now flooded with electricity from home panels.

We set off down along the beautiful residences of Military Row. Hell in Paradise had become Paradise in Hell. As we walked by No.10, we saw Helen on the front porch. We asked her about medical care on the island.

‘There’s not much that’s much good.’ She said. ‘Anything serious costs $A25,000 to fly off the island. Most older residents must leave to spend the last part of their lives in New Zealand or Australia.’ She invited us to have a look inside.

‘It was built in 1844, as the residence for Thomas Seller, the first Foreman of the Works, and his manservant.’ She said. ‘The Young family who moved in for 34 years, from 1856, had fifteen children.’ The pink and mustard and apricot interior seemed far too small to house that many, but it had been restored with white wainscoting and fireplaces, fine desks and dressers and round tables, and elegant display cases for the blue and white Wedgewood that Joan had found so fascinating. A wall of pink and white periwinkle and red geraniums lined the interior colonial period garden, with a red hibiscus over 150 years old.

We reemerged onto the front veranda. Helen had pulled up the aerial on her red and metal ‘Vintage’ radio.

‘I like to listen to the cricket.’ She said. ‘It’s starting soon.’ But we still had time to see how she had softened, with knowing us a little better.

‘I could tell you stories.’ She said. ‘There are more here than anywhere else on the Southern Sea.’ I told her about Darren and his comment about how the Pitcairners would know how to deal with the Aussies, when the time came.

‘Live in hope, die in agony.’ She said. ‘Which Darren was it?’ I gave a general description.

‘That’s Darren X.’ She said. I asked how many Darrens they had.

‘Too many.’ She said. ‘Those boys are on a permanent tagalong tour.’ Helen told us about the old days of the Pitcairn arrival, when ‘nobody slept in the same bed twice.’

‘And no one was sure who their father was. No. 5 Quality Row over there was the brothel.’ She said, pointing over to the curved stone wall of Government House. ‘The Aussies aren’t much better. Labour sends career bureaucrats, and the Liberals send retired politicians. The police helicopter runs interference for the chief’s trysts. When the governor flies home, the only thing left is the dining room table. A carrion perch.’ The talk turned to the current prime minister.

‘She’s giving the country away.’ Said Helen.

‘And there’s no more archeology allowed for me to do here,’ Said Helen. ‘Since they made the place a World Heritage Site in 1965. I’ve got three cats at home. The other day one of them brought me a rat with a five-inch tail.’ She pulled a can opener out of her handbag, and then a can.

‘I always have creamed rice for lunch.’ She said and turned up the cricket game on the radio.

And then I saw it. Despite all her knowledge, she didn’t know how to get back to her native Australia. Helen, the free inquiring authority on all things Norfolk, had become a captive lifer in her area of expertise, too poor to go home. She must have seen my look. The cricket volume was squelched, for one last musing.

‘You know, the horses start to run around the common before someone dies.’ She said. ‘And they don’t stop until the funeral is over.’ The crack of a fly ball careened off the roar of the crowd.

It was another ball game venue we pulled up to, a few metres further down Quality Row. It could have been a Canadian flag flying over the Point Hunter Reserve, but the red was green, and the maple leaf was a Norfolk pine.

‘Where else can you play golf on a World Heritage Site for seventy bucks a week?’ I asked. Robyn and I checked out the pro shop, where a cartoon depicted a convict swinging his ball and chain over his head in an arc. Norfolk Island Ball Game. The single harried Boxing Day worker in the clubhouse kitchen was having a back-and-forth cheeseless meltdown of palindromic proportions.

‘I’ve got no food.’ She agonized. ‘I can make you a focaccia, if you’re desperate.’ We were no longer sure what that word meant on this island, but we knew it didn’t apply to us.

But if Golf is a game to be played between cricket and death, our next Quality Row stop appeared right on cue. Wayne had told us that, if we wanted a cheap funeral, and arrived on a one-way ticket, Norfolk would still bury you.

‘If you’ve carked it,’ He said. ‘You’ll arrive on a different part of the plane, bearing two cold cartons of beer for the diggers, and a backhander for the clergyman.’ There were no crematoria, stonemasons, or undertakers on the island. The government would provide you with a coffin and a wooden cross. If you wanted a headstone, you would need to bring one from overseas.

Although that hadn’t been a problem in the old graveyard on Cemetery Bay. Here the headstones stood resilient against the headwinds buffeting the southern coast. And here there was a bounty of buffetts, and a buffet of Buffetts from the Bounty. They were all there with the convicts and soldiers, children, and murderers, side by side, beside the same beautiful ocean that could have taken them home.

The snorkelling gear in the back of the Mazda cried out for release. Robyn and I crossed over the legend of Bloody Bridge.

In the time of Major Anderson, a labour gang was constructing this beautiful little bridge. Leg irons, some weighing as much as 22 pounds, impeded every step of every convict. Rations had been adulterated by ‘Potato Joe,’ a merciless one-eyed Scot who substituted spuds for the bread the men were meant to have. Dysentery gnawed at their vitals. Already half-crazy, they were provoked by the overseer, hoping for a flicker of protest. Immediate retribution, in the form of the cat-o’-nine-tails, would fly at any offender. One of the prisoners exploded and drove a pick through the brain of his tormentor. Knowing that every one of them would be punished, the gang walled up the bleeding corpse in the bridge. When the overseer’s relief turned up at midday, he asked where his predecessor was.

‘Oh.’ They said. ‘He went for a swim down in the bay. We think he must have drowned.’ But then, and unfortunately for them, something bloody began to ooze through the still wet mortar between the bluestones.

We parked in the shade of a tall pine, put on masks and snorkel and fins, and slid into Emily Bay. The water came as a cool crystalline relief from the hot blood and gore of the day. Robyn and I held hands with each other and the current and undulated among the parrot fish and ‘sweet lips’ pink trumpeters, and even the big sting ray with a humped head like a wide-body 747 cockpit.

That night we splurged at Hilli Restaurant, discharging the credit card and recharging our souls. I couldn’t help but notice the word ‘decadent’ decorating the menu, as if ‘a state of moral decline’ needed defining on Norfolk.

The real decadence returned in my dreams, with visions of bloodstains between the grains, seeping through the creamed rice.

***

The next day, we pulled into the Returned and Services League driveway.

‘You want to have lunch at the club?’ She asked.

‘Have a look around.’ I said. ‘There’s always some history inside.’

The first thing that greeted us was a hallway of glass guncases, behind which were likely most of the weapons used in all three of the wars. The second welcome came from a massive Aborigine behind the bar.

‘First time?’ He asked, keeping an eye on some of the more intoxicated patrons at the adjacent pool table, with a peculiar blue velum. An old tin helmet lay on the bar, a rough slit in the top, for tips. The word ‘Legacy’ was written in marker under the slash. Ring for Drinks. The walls were covered with desert photos of ‘Departed Comrades,’ in shorts and Aussie slouch hats. On this island, conflict was inescapable. The suspicious manager approached us.

‘You come to the bistro for lunch, or what?’ He asked. I told him we were thinking about it. He shoved two menus into our hands and waited.

‘That’s alright.’ I said, after absorbing the sticker shock, the melange of mealtime and murdered mates on the walls, and the incongruity of the description of the place as a ‘bistro.’ ‘We’re not that hungry.’

But by the time we had a snorkel, and made it to the market, and back to the cottage in the late afternoon, our appetites had sharpened. We had purchased two steaks at the butchers, an imported one from New South Wales, and another local leaner Norfolk Blue specimen.

I lit up the brick barbeque, under the choirboy-collared palms and tree ferns in the back yard and waited for the scented Norfolk pine to burn down into embers. Even still, the meat would taste of sap. The Aussie steak won hands down.

The day before we were due to leave, Robyn and I set out to see most of what we had missed so far. The most liberated lifeforms in Norfolk had always been the birds, and Wayne had suggested we take in the One Hundred Acres Reserve, up Rocky Point.

‘Go early.’ He said. We left the lodge between the dawn chorus of the Pacific Robins and the rush hour traffic of the Golden Whistlers. I didn’t expect much. Norfolk Island and Lord Howe have by far the world record of bird extinctions in Australia.

When the Sirius was wrecked on Norfolk Island in 1790, and 270 extra people joined the few first settlers, there was too little food to feed them all. They soon discovered that by lighting fires at dusk, a type of petrel would ‘drop down out of the air as fast as the people can take them up and kill them.’ Three thousand birds were taken, every night for two months, and named the bird of providence. But fate frowns and, not long after, the deafening aerial chatter of courting Providence Petrels became extinct on Norfolk Island.

Since 1774, four endemic bird species and five subspecies have disappeared. The Norfolk Island kaka and pigeon, which were so common when members of the First Fleet landed in 1788 that they described them as pests, were exterminated by hunting and forest loss. But the rats and cats took out the Grounds Doves, Starlings, Trillers, Guavabird Thrushes and pure Boobook Owls, and the White-chested White-eye is on the verge of annihilation.

The entry to the reserve was darkened by heavy branches, reaching overhead from enormous Morton Bay fig trees on high curved buttressed roots, a forest from the innermost recesses of Tolkien’s imagination. It spoke of ghosts and fallen comrades.

For the first ten minutes, we saw nothing. Then two ethereal white terns appeared on their bough at black beak and eye level, inches away, watching us watching them. As the track wound down to the ridge, the Black Noddies began to surround us everywhere, in the air and in their flimsy nests in the pines. Fluffy Masked Booby chicks, bigger than their parents, swayed on branches or, if less fortunate, waddled in hedges underfoot. Here were the eggs of the same Sooty Tern that had produced the Rapa Nui Birdman cult which had been harvested by the Islanders, who called them Whale Birds. And here were other kinds of petrel and shearwater and gannet and ternlet, soaring and nesting. We emerged onto magnificent precipice, where turquoise and green collided with the rocks under the Tropicbirds, hanging in the wind blowing up the cliffs.

The trail turned into a copse of White Oak, and I made a big heart of their China pink hibiscus flowers for Robyn, like I had in Sulawesi. An arrow pointed towards our destination. Rocky Point- Exposed Roots, Muttonbird Holes. And the path wound into a big green moss Eden, under beautiful tall tree ferns, and towering ficus, and pentagonal starred Norfolk pine saplings sprinkled with red flowers from their neighbours. It was like strolling through Christmas.

The Salty Theatre on Norfolk was where tour operators took their groups to experience the local canned version of Mutiny on the Bounty. I had no burning desire in the performance, but there was something about the idea of posing and playing on the outdoor Bounty replica stage that required a break-in. And so, I found myself a bounty hunter, crawling through the vegetation allowed to flourish to prevent such a raid, and appearing on the deck in front of hundreds of empty seats, and Robyn.

As cosmic time is counted, Norfolk Island and Pitcairn Island were twin volcanic peaks, rocketing out of the ocean floor. Both lay uninhabited for three million years until, in the closing years of the 1700s, Norfolk became a penal colony, and Pitcairn a hiding place for Bligh’s mutineers. In 1789, as Sirius died on the rocks of Norfolk, Bounty was incinerated at Pitcairn. In a bizarre cyclic saga, the Pitcairners, whose ancestors had escaped transportation to Norfolk as convicts, found themselves its new owners, the bounty from the mutiny. Max had provided us with an abridged version of the original. ‘In 1789, a mongrel mob stole a ship, picked up their mates, burnt the ship, and marooned and unable to speak to each other.’ He said. ‘Wound up climbing up the wall and blowing spit bubbles.’ It was still the recipe for a classic Story of the Southern Sea- iconic sailing ships and stormy seas and muskets arriving in an exotic romantic tropical Shangri-la, good-natured good guys having good-natured fun, but this time becoming pirates and castaways on their islands. When Bligh and that part of his crew was set adrift in their longboat, had he known that the new Norfolk colony was thousands of miles closer than the Timor he was making for, the island might have seen the descendants of loyalists living alongside those of the mutineers.

But it didn’t happen like that. It happened that, after all the bloodshed between the English mutineers and the Tahitian men, only one adult male, a Cockney orphan named John Adams, was left alive. He spent his days filling himself with the holy spirits from the salvaged Bounty Bible and prayer book, and those made from Pitcairn ti-tree root juice. The second was more potent. One night a vivid hallucination of the Archangel Michael attacking him with a dart remade him as a Patrirach. Moses of the Mutiny, he transformed the twenty-three young hybrid minds left on the island into ‘the world’s most pious and perfect community,’ one of the great historical ironies. They hid from the world for eighteen years, ensuring that no fires burned during the day.

When Captain Folger arrived at Pitcairn on the American whaler, Topaz, he described a Rousseauian race of ‘Noble Savages… tall, robust, golden-limbed and good-natured of countenance.’ He had discovered a community of athletic surfers with an unquestioning belief in Divine Providence, honest, and all working for the common good. No one had ever seen all that nailed together before. But it would become too successful to be self-sustaining.

In 1855, because of overpopulation on Pitcairn, Queen Victoria offered Norfolk Island to the mutineers’ descendants. At least that’s what they thought the terms were. For the 194 Pitcairners who sailed the seasick five-week journey on the Morayshire in 1856, their first impressions on landing were those of gratitude, joy, grief, and astonishment.

Massive stone buildings appeared as castles, and the cattle and horses were the first they had ever seen, as were gardens of English flowers and exotic new fruits and vegetables. Lavatories were a complete mystery. Anything with wheels became novel sport, pushed down the nearest hill and smashed. Furniture exceeding the bounds of functionality became fuel. The Bubuck owls, and the moaning echo calls of the ‘ghost bird’ wedge-tailed shearwaters, terrified their nights.

But the most horrific revelation came with the realization of what had happened on Norfolk before their arrival. The inhumanity of the punishments meted out to the convicts terrorized them to their marrow. Who were the criminals? Who were the virtuous? The gibbet in front of the prison was hurled into the sea.

Captain Denham had left them well-provisioned and Governor Dennison gave each Pitcairn family a fifty-acre block of land. But he also gave them an annulment of their ownership of the island, as instructed by the Colonial Office, a betrayal that formed today’s seeds of Darren’s new mutiny.

And so, the question, again. Who represents the savage and who the civilized? Rousseau would pick the barefoot, uneducated Pitcairner as the very best society; Hobbes, the social contractor, insisting that the nature of man in nature is evil, and must cede rights to government as the price of peace, had never experienced the ‘peace’ on Norfolk.

There is no record of my performance of Mutiny on the Bounty, from that thespian day on the deck of the replica. Instead of being driven from the stage, we drove from the stage, past an iconic scene of a derelict old moss-covered dory on its side, under a Norfolk palm, under a Norfolk pine. The owner of the property caused us red-handed, taking photos, and waved the Norfolk wave as she went down her drive.

For what we thought would be our last night in the ne plus ultra, Robyn and I drove back under the Morton Bay fig trees and the Norfolk Blue Restaurant. We had met the charming pioneer of the blue-grey breed of native hybrid cattle, earlier in the day, chasing a reservation after our walk through the reserve. Her first name was also Robyn, and her last name came from Paul ‘Jap’ Menghetti, the owner of the hundred-acre farm of rolling hills and a 19th-century Norfolk Pine homestead of eclectic artworks, old photographs, and crystal chandeliers, whom she married in 2002. Robyn had come from Melbourne, after working on a dried fruit farm. She seated us in front of a water carafe imprinted with the name of the estate. Mildura.

‘You collect crockery like you collect cattle?’ I asked. And she grinned. Robyn had collected every one of the ‘mongrel’ blue cows she could find on the island, all thought derived from an Angus-Shorthorn blue bull cross, that had played with the other Herefords and Friesians and Red Devons and Murray Greys.

‘We’re not paddock-to-plate here.’ She said. ‘We’re conception-to-plate. You must try our house specialty.’ A waitress appeared in short order, with a large tattoo on her neck, and a Norfolk Blue beef pâté, with caperberries, crostini and homemade chutney. We spent the evening sandwiched between the New Zealand High Commissioner, and the current Governor, to whom Robyn later admitted she had been ‘absolutely septic to.’ We loved her style, and wished her all success, as we left.

The weather changed on the morning we were supposed to leave, and my Robyn, who gets a bit more concerned about the forces of nature than I do, was less placid than the cows we ate the previous evening. I knew this because she told off the Japanese greeting that came out of the Mazda’s speakers whenever we started it up.

We had enough time before our flight to drive Up Cooks, to see the compulsory Captain Cook monument north of our cottage. His statue at the headland was surrounded by pink hibiscus and magnificent views of the plate-shaped rocks offshore.

We drove past a basalt formation decorated with strange pale, green-painted egg-shaped rocks, into Burnt Pine. The only taxi rolled by, a black London cab, which charged $5 for journeys inside the cattle grid that keeps the cows out of the commercial centre, and $10 to anywhere outside it.

Our stay was about to get even more memorable. We drove round ar airport, round ar plane, and left the Mazda to its own devices, keys in the ignition. We checked our baggage and our emails, and stood around in the terminal, clutching our boarding passes. I watched the Air New Zealand flight bounce off the runway.

‘That must’ve hurt.’ Said Murray, an engineer from Christchurch.

‘Bloody Oath!’ Agreed a nearby Aussie. I watched the poor plane trying to do an impression of the Sirius shipwreck until the pilot managed to regain some kind of control from his hard landing.

‘Must be mechanical.’ Said the Maori bloke.

‘Must be.’ Said Murray and me in unison. And as if he had been prompted, the pilot appeared in the boarding lounge, confirming that like the many who had come before, he had landed a ‘machine for extinguishing hope.’ The flight, for today, was ‘delayed.’ But if we weren’t leaving today, shouldn’t the more appropriate description be cancelled? And the more he tried to reassure us that everything was being done, the more we became convinced that he didn’t know if anything could be.

‘It’s kind of like your lawnmower.’ He said, apparently drawing a comparison to what had happened to the hydraulic landing gear.

‘Jeezuz.’ I said. ‘If this bloke thinks he’s flying a lawnmower…’

‘Bloody oath!’ Said the Aussie. Murray and the Maori and I looked around, and then at each other. Another day in Hell in Paradise.

‘Governor’s Lodge for lunch?’ Asked Murray.

‘Bloody Oath!’ Said the Maori and I, in unison. An entire airplane arrived for lunch. The black waiters lost their smiles, and the skies opened with black rain.

At the South Pacific Lodge, I asked the receptionist how we would know when we would be able to leave.

‘Listen to the radio.’ She said. I told her that we didn’t have a radio.

‘Check the bulletin board.’ And she gave us keys to a terrible room that smelled, and then other keys to a terrible room that didn’t, with a view of nothing.

The food was even more unfit for human consumption because of the rush on the unfortunate Filipino servers, who discharged the bland-colored contents of the heating units into the plates of the discharged detritus from the plane. They served horrible ham, terrible trevally, and chunderful chicken. And there wasn’t enough of it, or too much.

‘Is this your second time?’ Asked the overseer, as I was thinking about how to mortar her remains into the bridge.

‘It’s not a reward.’ I said, helping myself. We checked the ‘Disruption Advice’ notice on the bulletin board later. The advice was the same as the ‘Disruption Advice’ notice on the Sirius. Come back tomorrow. Back in the terrible room that didn’t smell, I broke my right fifth metacarpal on the ceiling fan.

The sun cracked the heavens wide next morning. Breakfast is a notoriously difficult meal to serve with a flourish, but no one needed to be worried. We were escaping. The excitement among the castaways was palpable.

Most departure lounges smell of freedom. This one was more complicated. Yorlye kum baek sun.

Table of Contents

Lawrence Winkler is a retired physician, traveler, and natural philosopher. His métier has morphed from medicine to manuscript. He lives with Robyn on Vancouver Island and in New Zealand, tending their gardens and vineyards, and dreams. His writings have previously been published in The Montreal Review and many other literary journals. His books can be found online at www.lawrencewinkler.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

Thanks for the warning. I’ve cancelled my planned vacation on that Paradise Island. I will schedule for a stay at Adam’s Town on Pitcairn instead with a visit to Christian’s Cave.