Ala Wai Aloha

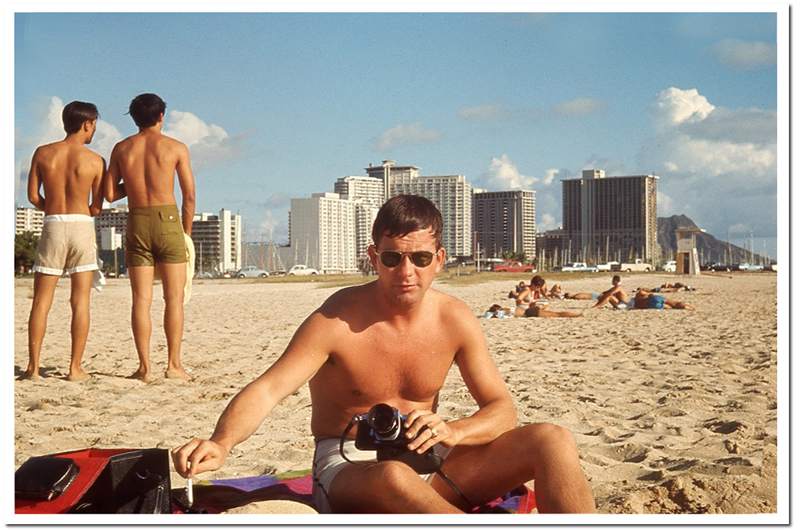

An old photo (above) appeared in my inbox the other day, a kind of flashback; sent by an old mate, a chap I have known since our days in South East Asia. Strange how friends forged in the fire and fog of war endure like no others. Dave W is a Hapa Haole, an O’ahu native with Hawaiian blood; polite Hawaiian for mutt.

After Vietnam, I was slated for a tour in Hawaii, at PACAF HQ, Hickam AFB. Dave gave me a parting gift as I left Saigon; two phone numbers.

The first number was for his sister, the second for a namesake, a fellow University of Hawaii alum, Dave K, then doing graduate work and living aboard a double ender sloop, Shogun, in the Ala Wai yacht harbor. I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but those two phone numbers were a kind of language tutorial, a beginner’s lesson on the meaning of aloha.

Aloha is one of those words that defies precise definition; it means hello, goodbye, and all the civility you might show or experience in between. Hawaii is, if nothing else, seductive. If you stay long enough to go through a tee shirt and two pairs of flip-flops, it’s difficult to find a good reason to leave.

I left Vietnam for Honolulu at the end of 1968. Vietnam and mainland America alike were ablaze with war, anti-war and civil rights conflicts at the time. I thought I might be going from pan to fire; certainly not prepared for the culture shock of going from combat to Waikiki.

For me, the slow-motion tragedy of Vietnam put the lush comity of Hawaii in bold relief.

The charm of the islands had little to do with scenery or climate and everything to do with people. Hawaii is arguably the most diverse state in the nation. Caucasians are a minority in Hawaii. The majority are a polyglot mix of natives, Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Filipinos, Portuguese, assorted Europeans and mainlanders.

Tolerance is the poi that binds. For me, the people of Hawaii and aloha culture were the perfect antidotes to 1968 and all the sturm und drang of early 70’s America.

Dave K was a Kama’aina, a non-Hawaiian local. His father had been a Dole plantation manager, a luna in the vernacular. At the time we met, Dave was a sun-bleached harbor rat; surfer, student, sailor, SCUBA diver, and beach .jpg) volley baller. Ala Wai Dave introduced me to surfing and diving; too late in life to ever be good at the former, but perfect timing for diving. I was encouraged to get certified at Pearl Harbor and the rest of my water story is culinary legend. For four years, my freezer had only two comestibles, ice cubes and lobster tails.

volley baller. Ala Wai Dave introduced me to surfing and diving; too late in life to ever be good at the former, but perfect timing for diving. I was encouraged to get certified at Pearl Harbor and the rest of my water story is culinary legend. For four years, my freezer had only two comestibles, ice cubes and lobster tails.

As an engineering student, Ala Wai Dave was employed to survey sand movement between the inner and outer reefs off Waikiki. Hotels were losing their beaches. Dive safety called for a tag team. Whilst Dave K followed colored sand samples, I filled my netted inner tube with Slipper or Spiney lobster.

As an Intelligence briefer, I often worked an early shift at PACAF HQ and had afternoons to myself. ‘Ewa Beach on the other side of Pearl Harbor was a good spot for free diving, no SCUBA tanks needed.

Free diving might be the best exercise program on the planet.

Leeward O’ahu is relatively calm at low tide and, if you find one slipper lobster, you often find a bunch. Lobster must be taken by hand off the main islands, no traps and no spears, making the hunt an adventure for diver and crustacean alike.

Fortunately, a lobster is predictable, like politicians, they move in one direction, backwards.

On one placid and productive afternoon, I was wading in with my catch and a picture-postcard Hawaiian girl appeared behind the low coral stone wall that separated beach and surf from residences. The vision, with waist length hair flowing over a halter and sarong, waved me in and asked if I had taken any Wana (pronounced Vana).

.jpg) I had no idea what she was talking about.

I had no idea what she was talking about.

After introductions, Malia informed me that Wana was a spiney sea urchin, much prized and eaten raw after roasting the spines off the center shell. I never developed a taste for urchin, but that beach encounter led to many an invite to the ‘Ewa beach house where aloha was always on the menu. Malia was a flight attendant (nee stewardess) for Aloha Airlines and her ha’ole husband was a former Navy pilot then flying for Aloha too.

After six months in the Hickam bachelor’s quarters, I migrated down to the beach on the Ala Wai Canal. The canal is what prevents Waikiki from becoming a swamp. For GIs in those days, the “beach” was Waikiki.

The Ala Wai Canal separates Waikiki from Honolulu.

At first, I shared an apartment with another USAF officer who was memorable for his tan and fetish girlfriend. RB’s lady spent her days at Ala Moana Beach and never got wet, never. She was so obsessed about tanning that we called her “Cotton Balls.” She separated her toes with wads of cotton to brown her tootsies so that no white showed when she walked barefoot.

Six months of nervous proximity to Cotton Balls drove me to find a home of my own.

My new apartment was set in a splash of two-story buildings nestled under a grove of palm trees along the canal. The Ali Wai Apartments were managed by the irrepressible Mrs. Parrot (sic), a kindly matron who had a motherly interest in bachelor GIs. For Mrs. Parrot, all serviceman, even in paradise, had to be homesick. If you were remiss in leaving your laundry in the common dryers overnight, you would find your colors separated and neatly folded in Mrs. Parrot’s office the next morning, a kind of laundry aloha if you will.

The mistress of Ala Wai Apartments was also a free-lance yenta; compelled to mentor all the singles in the complex. One morning, as I was recovering my shorts and tee shirts, I was introduced to Barbara R, a nurse at nearby Kaiser Hospital. As coincidence would have it, Barbara was the then girlfriend of Ala Wai Dave.

Coincidence and serendipity are daily drills in island communities.

.jpg) Out of uniform, Barbara lived in a bikini and frequented the Hilton Lagoon (right) at the Ala Wai end of Waikiki. She was in every sense the Florence Nightingale of the Ali Wai, providing aid, comfort, and medical advice to the denizens of the yacht harbor who always suffered from a variety of harbor hazards; hangovers, brain freeze, heart break, sun burn, road rash, coral cuts, food truck trots, and unemployment.

Out of uniform, Barbara lived in a bikini and frequented the Hilton Lagoon (right) at the Ala Wai end of Waikiki. She was in every sense the Florence Nightingale of the Ali Wai, providing aid, comfort, and medical advice to the denizens of the yacht harbor who always suffered from a variety of harbor hazards; hangovers, brain freeze, heart break, sun burn, road rash, coral cuts, food truck trots, and unemployment.

Nurse Barbara was the consensus favorite in our crowd, a gratis practitioner who may have been born with aloha.

The yacht harbor was populated by a demographic that partied more than they labored. Happy hour and free Pu Pus (appetizers) were standards up and down the beach. Some joints had day-long happy hours. One such oasis was the Fort DeRussy Barefoot Bar, sited on a prime slice of Waikiki real estate a short walk from the Ala Wai. The bar was a circular affair under an ancient Banyan tree in the center of one of the few green spaces left in Waikiki. In those days, DeRussy had a From Here to Eternity vibe. Many a beach adventure began or ended with a few adult beverages under that iconic Banyan tree.

The Barefoot Bar and WW II era cottages are gone now, replaced by a ubiquitous and predictable high-rise hotel, Hale Koa (literally, Warrior House).

There wasn’t much incentive to be employed or entrepreneurial at the Ala Wai. Slip rent was nominal and there were always free Pu Pus at happy hour. There were, however, notable exceptions.

One such, was another Ala Wai tag team, Jerry and Trish, proprietors of a harbor haberdashery for boats. These two lived aboard a catamaran, Old Blue, a few slips sown from the sloop Shogun. Their specialty was any canvas sailing necessity: jibs, spinnakers, mainsails, deck shades, and cockpit covers. Jerry and Trish bought some big scissors and a used industrial sewing machine and went into business dockside.

Jerry and Trish offered sails of many colors, as long as they were blue or white.

Any harbor with live-aboards is a kind of sea going trailer park. Folks who reside on boats are usually cash poor and communal. Shared work ethics are a necessity. If your boat needs to be hauled out, scraped, or painted, it’s often .jpg) a community effort, followed by beer and grilled anything. Boat maintenance in the sun is thirsty work and often a party prelude.

a community effort, followed by beer and grilled anything. Boat maintenance in the sun is thirsty work and often a party prelude.

Shogun and Big Blue were perfectly berthed to observe the tourist traffic coming and going on the blue Ilikai Hotel ramp, a runway which descended to the edge of the Hilton Lagoon (right). Many a comely tourist was recruited off the Ilikai ramp to participate in harbor festivities.

The café on the edge of the lagoon was the nearest sit-down eatery to the Ala Wai, frequented early in the AM by harbor rats for breakfast. In those days, Hilton served the perfect Hawaiian breakfast; two eggs over rice, “portagee” sausage, half papaya with lemon, washed down with fresh pineapple juice.

A plethora of eateries could be found at the Ala Moana Shopping Center too, just a short walk over to the mauka (mountain) side of the bridge over the canal. I was introduced to the culinary wonders of SPAM at Ala Moana. Prior to my idyl in O’ahu; for me, SPAM was a kind of mystery meat.

.jpg) The acronym is still a mystery, a variable to this day. Some say SPAM stands for “special Army meat” and others say “special American meat.” Cynics and haters use adjectives or nouns that can’t be printed here.

The acronym is still a mystery, a variable to this day. Some say SPAM stands for “special Army meat” and others say “special American meat.” Cynics and haters use adjectives or nouns that can’t be printed here.

No matter, SPAM is almost as popular as vowels in Hawaii. Since WW II, the Hormel product has been a staple of island diets across the Pacific as far as Japan.

Fried ground pork, pig suet, and salt; what’s not to like?

In tropical Hawaii, where exercise in the sun is a daily event, you might think of SPAM as the military does, a kind of salt pill, a prudent dietary supplement to replenish or supplement precious bodily fluids and other nutrients lost to sweat.

Whatever the rationale, nobody does Uncle Sam’s SPAM like a Hawaiian.

We tend to remember only the good times in places like Hawaii, but the most vivid memories always circle back to people, even professional colleagues. I lived on O’ahu when the war was supposed to be winding down. Fresh in my memory was Lyndon Johnson, who resigned, or chose not to run really, while I was keeping my head down during the Tet Offensive in ‘68.

At the time, I asked myself, and others, what we were doing in Vietnam if the President could just walk away, indeed divorce himself from a nightmare that his party had created? Lyndon Johnson went back to his cows and Cadillacs while soldiers continued go home in body bags for another seven years.

Johnson’s cowardly behavior precipitated a sea change in my personal politics. Partisans like to suggest that Vietnam was Nixon’s war, forgetting that Johnson made Nixon possible.

My faith in government was restored, in part, by several military dinosaurs gifted to Hawaii by the greatest generation, the most memorable of which was Admiral John McCain II, son of another distinguished sailor, and father to John McCain Jr., then a prisoner of war in North Vietnam.

.jpg) At the time, “Jack” McCain (right) was CINCPAC, commander of all US forces in the Pacific. Most prisoners were USAF crew members, so the Air Force had the wheel on POW matters. Periodically, we would take the launch into Pearl Harbor to brief McCain senior.

At the time, “Jack” McCain (right) was CINCPAC, commander of all US forces in the Pacific. Most prisoners were USAF crew members, so the Air Force had the wheel on POW matters. Periodically, we would take the launch into Pearl Harbor to brief McCain senior.

Truth is, we usually had little to tell the admiral except scuttle butt and news reports. I was a POW briefer, not by virtue of expertise, but simply because I had already served in South Vietnam. McCain senior was very considerate with junior officers and often used our briefings as an opportunity to pick our brains about Vietnam or the good liberty on Waikiki. The admiral knew that POW Intelligence was an empty set, but he always appreciated the courtesy of a periodic update from PACAF on his son.

When there’s nothing to say, small talk often prevails.

McCain worried aloud one day that his son might embarrass himself, the family, or the Navy. Age is prescient. Just before retirement, in another candid moment, McCain senior conflated his son’s collusion with the NVA with Jane Fonda’s antics in Hanoi; a bit of candor that left me speechless.

Admiral McCain had few illusions about his son; as a man, a husband, an aviator, or a naval officer.

In retrospect, it is more than a little ironic that history remembers McCain junior, the egoist politician from Arizona, better than his father and grandfather, two real heroes who led America to victory in two 20th century wars. When “Jack” McCain retired in 1972, it was a little like watching the end of modern military history.

In contrast, when John McCain III was elected to the House 1982, I thought junior had found his calling. Better a fey politician than a loose cannon in the Navy. In retrospect, even Rolling Stone eventually broke with the pack in 2008 and dubbed McCain junior “the make-believe maverick.”

1972 was a bellwether year for me, my tour in Hawaii was about to end. I thought I might bail from military Intelligence and write for living. At the time, I was naïve enough to think both professions had integrity in common.

With help from the brass at Pearl, I caged an interview with the publisher of the Honolulu Star Bulletin (nee Honolulu Advertiser), Thurston Twig-Smith, a direct descendant of one of the missionary families that overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy. “Twig,” as he liked to be called, opposed Hawaiian sovereignty to his deathbed in 2016.

Our interview in ’72 did not go well.

For openers, Twig asked me if I knew how many “kids” came to Hawaii each year thinking they would be writers. At that point, I had served in combat twice. Being called a “kid” by some trust fund twit made me want to smack the smug off Smith’s face. When the conversation turned to salary, conditional at that point, Twig-Smith mentioned a top number that was less than half my salary as a USAF captain.

I was gob smacked to learn that Military Intelligence paid better than journalism.

Aside from being patronized, what I remembered most about that interview was that Twig-Smith reminded me of every journalist I had ever met in Vietnam; arrogant, entitled, and condescending. Journalists covering any war know that one bad press report can end an officer’s career.

Flag officers take a knee before the Press long before they will fold in combat.

I retreated back to Hickam where my sympathetic boss offered graduate school as a kind of consolation prize. A master’s degree in Intelligence at government expense seemed to be a good idea at the time, so I took the road most travelled. Hard to believe, today, that I traded Honolulu for Washington, DC.

Thusly, did a job in Intelligence become a career.

ALOHA ‘OE

.jpg) In those days the Pentagon was trying to subsidize the Matson Lines, the last American flagged steamship line carrying passengers between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Honolulu. If you had served a tour in Hawaii, Uncle Sam would pay for a passage back to the mainland by cruise ship, a parting not as romantic as you might think.

In those days the Pentagon was trying to subsidize the Matson Lines, the last American flagged steamship line carrying passengers between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Honolulu. If you had served a tour in Hawaii, Uncle Sam would pay for a passage back to the mainland by cruise ship, a parting not as romantic as you might think.

Mother Nature and Queen Liliuokalani conspired to make me regret leaving the Ala Wai. The SS Lurline (right) sailed at sunset, with Diamond Head and the Punchbowl aglow like a Thomas Cole landscape. As the harbor tug pushed the Lurline away from the quay; on cue, the Royal Hawaiian Band struck up Liliuokalani’s Aloha O’e, the beautiful hymn to lost sovereignty, goodbyes, and longing. Queen Liliuokalani (below right) was a poet and beloved renaissance royal, Hawaii’s last monarch.

.jpg) My heart dropped into my stomach as I looked down on my overserved Ala Wai friends waving frantically on the wharf. Departure had been preceded by a raucous onboard party.

My heart dropped into my stomach as I looked down on my overserved Ala Wai friends waving frantically on the wharf. Departure had been preceded by a raucous onboard party.

My then-girlfriend, Rita, looking for all the world like a lost puppy, gestured at me up on the rail to throw my flowers overboard. Hawaiian lore has it that if you throw your leis onto the water, and they float back to shore, you will return someday. I held my flowers until well after dark, well out to sea; then gave the leis to the waves.

That evening, as I watched the best years of my life recede into the wake of the SS Lurline, I knew that I had reached a personal point of no return. We never really appreciate what we have until it’s gone.

Aloha O’e, “farewell to thee,” indeed.