Alienation – A Pocket Guide

What style of diplomacy is to be recommended when dealing with Aliens?

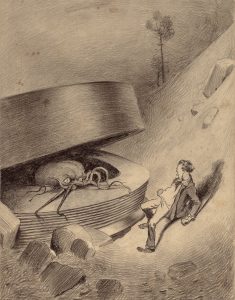

Illustration for The War of the Worlds by Henrique Alvim Corréa

by Steve Jamnik (March 2022)

The calibre of good Science Fiction is gauged, not only by the convincing nature of the idea, and the way in which the story is told, but also by its present-day relevance, and suggestive analogy. Forster’s ‘The Machine Stops’ and Harry Harrison’s ‘Make Room, Make Room’ are two examples. Science Fiction imagines not only what the future may bring, but what may go wrong, leading to ghastly, unforeseen consequences, as in Wyndham’s ‘Consider Her Ways’ and Crichton’s ‘The Andromeda Strain.’

The term ‘Science Fiction’ has a long pedigree. Possibly the earliest example of science fiction is Swift’s ‘Gulliver’s Travels.’ The story has all the necessary ingredients: strange worlds; madcap science; analogies; social satire. One could go back even further to the ‘Arabian Nights’ or ‘Beowulf.’

H.G.Wells’ 1897 novel ‘The War of the Worlds’ is an allegory. It is a critique of western imperialism. Alien creatures descend on an innocent, resource rich world and (literally in the case of the Martians, their bodies have no digestive system) suck the lifeblood out of it. The analogy is there to see if you care to see it. If you care not, then it is a jolly good story with a thoroughly happy ending, albeit with Humankind reduced almost to extinction.

In Wells’ novel the first Martian cylinder lands on Horsell Common just outside Woking in Southeast England, a real location a mile from where Wells was living at 141 Maybury Road. The Byron Haskin/George Pal 1953 film relocates the action to Southern California. The Martian cylinder crash lands in the hills of Pine Summit, ten miles from the town of Linda Rosa.

Still hot after having streaked through earth’s atmosphere, there come scraping noises from within the cylinder. A hatch unscrews, then falls off. A whirring, segmented, cobra-like proboscis emerges and scans the vicinity. Three locals cower in a ditch. They contemplate a tad of ad hoc diplomacy.

“We ought to let them know we’re friendly,” suggests the man wearing a brown fedora; and with that, having tied an old sugar sack to a stick, the intrepid locals carefully make their approach.

The Martian proboscis cranes down to bring the men within its sights. ‘Twang-twitter-twitter’ warbles the Martian proboscis.

“We welcome you. We’re friends!” the men eagerly cry.

Confused and alarmed by the flapping sugar sack, the Martians decide not to cut the sack any slack.

Sugar Sack diplomacy:

Later in the film, Pastor Matthew Collins makes an attempt.

“I think we should try to make them understand we mean them no harm,” he muses.

“They are living creatures out there … if they’re more advanced than us they should be nearer the Creator for that reason. No real attempt has been made to communicate with them.”

In an improvement on a sugar sack, he holds a Bible up before him. As he advances towards the Martian machines, buoyed above him on magnetic flux fields, he recites Psalm 23: ‘Though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death …’

You can see how that works out for him:

Bible diplomacy:

Sadly for the Martians, they have no resistance to the microbes in our atmosphere, microbes to which the Human Race, over its millions of years of evolution, has gained immunity. Whom we should thank for such good fortune is up for debate, although the closing scene of the film doesn’t mince words:

“After all that men could do had failed, the Martians were destroyed, and Humanity was saved, by the littlest things which God in His Wisdom had put upon this earth.”

Divine diplomacy:

There is of course another concept in ‘The War of the Worlds’ which is just as thought provoking.

The intractability of aliens, and the impossibility of intergalactic negotiation is a theme which Nigel Kneale explores in the four stories of his Quatermass franchise. From 1953 to 1979 the character of Professor Bernard Quatermass was played by six different actors (Andre Morell being the best.) Each story examines with impeccable logic the dilemma that alien encounters entail. As with Wells’ Martians, Kneale’s are pitiless and unreachable.

Different diplomacy [viewer discretion advised]:

The final Quatermass story, with John Mills slipping into Andrew Keir’s jacket, shirt and loosened tie, was produced by Euston Films in 1979. Hippies congregated at a neolithic stone circle are vaporised by a space beam:

Space beam diplomacy:

Surely some extraterrestrial misunderstanding? If only the aliens could be made to realise that we are reasonable people. They are hurting us, and we mean them no harm. We must try to communicate with them:

Shuttle diplomacy:

It appears that the aliens are not on our wavelength.

Scuttle diplomacy:

With both H.G.Wells and Nigel Kneale, the aliens cannot be reasoned with, and this is terribly disturbing. They cannot or will not listen. Why can they not be reasoned with?

It is because the aliens do not think as we do. Their goals are completely different from ours. They are not interested in our happiness or well-being. As far as they are concerned, we are a resource; material; livestock. They will utilise the world and everything in it as they see fit, and solely for their benefit, not ours.

Have no fear. Science Fiction is, obviously, fiction. There’s no need to take it too seriously, waking cold and wretched in the darkness of the night. It is a dystopian nightmare. Look around you. There are no aliens.

__________________________________

Steve Jamnik grew up on farms in South East England, studied psychology at University in the early seventies, worked as a Behavioural Psychologist for two years, then moved into television post-production. He is now retired.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast