An Anthropologist at Large

Interview with Geoffrey Clarfield

by Jerry Gordon (August 2022)

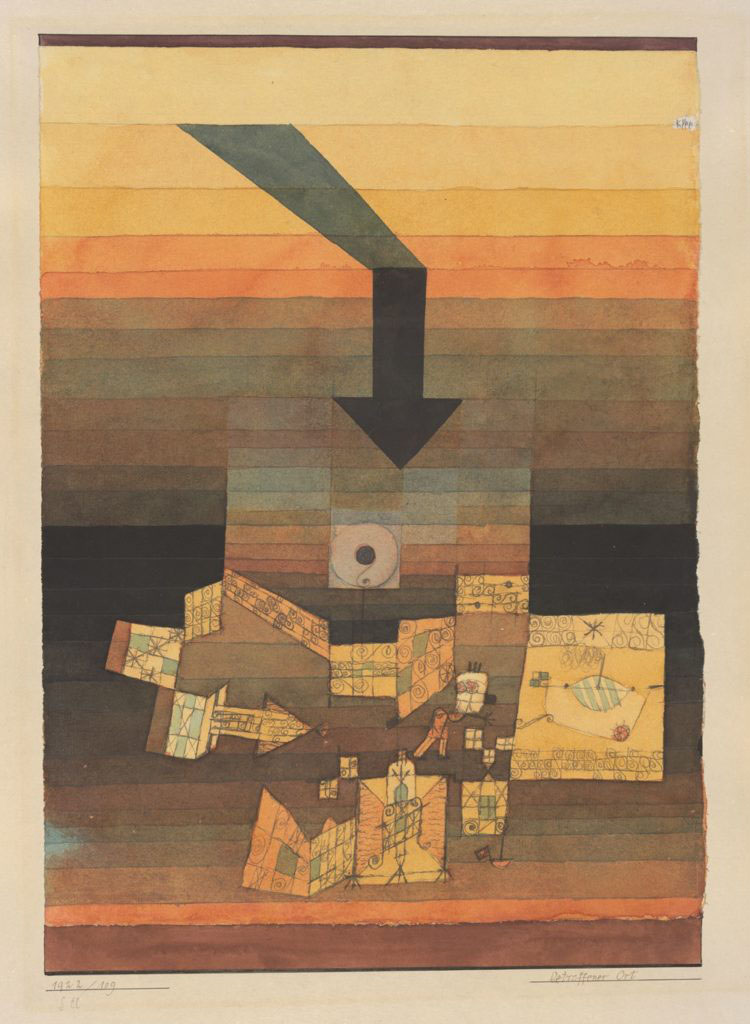

Affected Place, Paul Klee, 1922

Geoffrey Clarfield is a Canadian-Israeli and contributing Editor at the New English Review. He is a native of Toronto.

He has lived and worked across the globe as an anthropologist at large, at loose in the world of international development. Clarfield is an ethnomusicologist by inclination and as an anthropologist, a close observer of the dynamics of tribal versus modern societies in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

He came about his music interest as a talented boy soprano who became a member of the children’s chorus of the Canadian National Opera through training at the Royal Conservatory of Music in his hometown. Later, after an audition he would be invited to become one of the early teen performers in the Broadway production of the musical “Oliver” that came from London, England to America.

His family nixed his being away from home between the ages of 13 to 16. And so, a few short years later he dutifully went off to university in Canada, earning his academic credentials and many years later found his way back to music via a three-year stint in the Big Apple, exposed to Jazz clubs, African and Anglo-American music archives, and projects with the Alan Lomax Archive.

He did anthropological field work in Morocco and lived among the Bedouin in the Sinai. Years later in East Africa he met and assisted in developmental programs under the authority of the late, revered Richard Leakey, the noted Kenyan paleoanthropologist.

Clarfield lived and worked in Israel during parts of the eighties and nineties, marrying there. His family returned to Canada and now live in a country where the second Trudeau government is engaging in experimenting with laws that, if enacted by the Ottawa Parliament, would give extraordinary powers of martial law, denial of habeas corpus and free speech to the Liberal Premier, Justin Trudeau, and his minority party in parliament.

Trudeau’s father Pierre relished the prospect of a future Canada anchored in Rousseauian–Marxist ideology and not the British legal tradition. Today’s Canadian press and social media in Clarfield’s view have become paid advocates for these developments. Clarfield is disturbed by what is happening in Canada, our neighbor to the north and the prevalence of wokeism, both there and here, He is upset about the emergence of what he deems “soft tyranny” as they appear to many of us.

In addition to his commitment to Canadian and Israeli democracy he is concerned about the dynamics of democracy in both nations as the elites there ignore the wishes of those who elected them and then “pivot.”

He is an unabashed defender of the Abraham Accords that the Trump team helped to birth with agreements with the UAE, Bahrain, and Morocco. Like many of us he believes that the real solution to the Arabs who live in the Land of Israel lies to the East across the fabled river in Jordan as he argues that today Jordan is a state of Palestinians, so why not become a Palestinian state? Join me while we explore these issues together in the next few pages.

Jerry Gordon: I am Jerry Gordon a senior editor at the New English Review. I am here with a colleague who has a diverse history of activities across the globe. His name is Geoffrey Clarfield. Geoffrey was born a Canadian citizen and gained Israeli citizenship when living and working there in the 1990s. Is that correct Geoffrey?

Geoffrey Clarfield: Yes. That is 100% correct.

Jerry Gordon: How did you go from being a boy soprano at The Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, and end up becoming an ethnomusicologist, whatever that term means, and then an anthropologist which allowed you to work as an International Development Consultant for more than 17 years in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. What is the story?

Geoffrey Clarfield: Well, it started with a piece of Americana when I was five. I came home from summer camp singing Somewhere Over the Rainbow from the musical, the Wizard of Oz, (which was broadcast once a year on Canadian TV), to my dear late mother when I was five years old. Yes, Frank Boehm, Hollywood, Broadway, the whole bit, a significant piece of American culture, which was also part of Canadian culture at the time. I did not know that at the time. For me it was just a TV show.

As I sang to her, she thought to herself, “Well, the kid has talent,” so she took me to an older female cousin who was studying at the Conservatory in Toronto at the time, who then brought me to her teacher, and they agreed that I should study singing. I immediately got caught up with the beauty of classical music and classical singing and the social life of the Conservatory. Within a brief period, because Canadian media was just getting off its feet after World War II, I found myself in the children’s chorus of the Canadian National Opera, then on stage doing musical theater, television, and radio.

To my parents’ credit, they helped me compartmentalize that very well, so I had a normal middle class, suburban Jewish upbringing. I had a warm and loving family. I had to work hard at school, got an allowance, but had this show business thing which made me hyper aware of the power of the performing arts. When the sixties came, I fell in love with what is now called Americana, all the stuff that Alan Lomax found, and Pete Seeger performed and then, Ballads, Blues, Rhythm and Blues and Rock and Roll. By the time I got to what Americans call College, we call University – my musical horizons had widened even further.

I had heard Ravi Shankar and George Harrison, and decided to study comparative musicology, what came to be called world music, which led me into the disciplined study of what is known as ethnomusicology. Then I discovered that intellectually ethnomusicology is a branch of anthropology, decided to give that a chance as a career and ended up pursuing it quite seriously.

By the time I was drafting my doctoral thesis, in the early 1990s, based on field work in northern Kenya (I had already been in Kenya for 4-5 years), I saw the writing on the wall. I saw the basics of what we now call wokeness take over academia. It started off with Marxism, went to feminism, then it went to “indigenous-ism” and the flip side of all that was and is anti-Western, anti-white, anti-Jewish, anti-Israeli sentiment.

I saw the writing on the wall and realized, these North American colleges are not going to hire me. Instead hiring people to teach about “Africa” became a form of affirmative action. I realized I would be the last guy to be hired, as I was white, Jewish, Canadian, Israeli, Conservative and no friend of Marxism. It was as if the entire North American academic world was doing everything to negate every value and precedent of Western thinking going back to the Constitution of the USA and that is still the case. This is now confirmed.

And so, I decided to throw in my lot with the expanding and competitive field of international development which had not yet gone “woke.” I started doing research as a consultant, which was a wonderfully disciplining experience, as it really knocked any falseness of speech out of me that I had picked up in academia, forced me to think clearly, speak clearly, write clearly, and meet deadlines. At the time, it was really challenging, but I never looked back.

Slowly I climbed up, or was pulled up, the professional ladder, and from research I started managing development projects. I liked East Africa. I felt lucky and comfortable that we had fallen into life in Kenya and Tanzania. I must point out that Nairobi has a great Synagogue. I am still a member, at least spiritually. I was just there a few years ago.

International Development brought me full circle for as a Jew because it deals with the moral and material destiny of the world. It is an enormous movement, even though it has an enormous amount of swagger, arrogance, and falseness, but there is something worthwhile about it. You do want to try and get clean water, access to a clinic, and literacy to the rural poor and a certain amount of democratic peace and quiet. So that is how it happened. It was a natural evolution when I look back in it.

Jerry Gordon: So where did you do your fieldwork there and what did you learn?

Geoffrey Clarfield: The basic lesson that I learned was that all those cultural anthropologists who were so controversial, like Margaret Mead and Franz Boas, without getting academic, we were right. There was an early 20th century discovery that different societies have diverse cultures, that are defined as different spoken and unspoken sets of values. Call it software, like there is a software for being an American, there is a software for being a Brit and its complex.

Anthropology at its best, gives you the methods by which you can create a predictable handbook for either an entire culture or institution. My first self-experiment was Morocco. I went there from Israel which I visited first because of my interest in Jewish history. I volunteered on a Kibbutz and traveled around Israel. I got the feel for the distinctiveness of Israeli culture, in the anthropological sense. Then I went to Morocco for a few weeks. A few years later I threw myself into Morocco in 1977 for 3-4 months to get a taste of the Arab world.

That is when I discovered the pre-industrial mentality; eighteen million Moroccans, were not interested in science and democracy. They were and are interested in religion, prophets, saints, sacrifices, and portents. It knocked the socks off me. It is politically incorrect to say, but it was like living in the Middle Ages. It also had a wonderful exotic and romantic side to it, so that was the first culture shock that I experienced. That was self-funded, so I did not have to really do anything but experience and think about it. I have pursued my Moroccan interest through the library and have started writing short stories based on my understanding or misunderstanding of that surreal country.

I publish them in the New English Review

Then on a more serious level, I spent a year with a Bedouin tribe in Eastern Sinai on the border of the Negev. I went out there a week on a week off, each month and did the whole participant observation experience and that gave me experiential understanding of the tribal nature of the Islamic world.

One of the things that I picked up from my experience with the Bedouin and upon reading more deeply about the Arab world was that the Bedouin are the “beau ideal” of Arab Islamic culture. They are not thought of as country bumpkins by 98% of urban and sedentary rural Arab Muslims. One of the themes of the modern Arab Islamic world is therefore a desire to return to the pure “Bedouin Islam” what modern liberals call “radical Islam.” It is a bit like Japanese CEOs who see their industrial success as imitating Samurai warriors, whereas we see them as benevolent producers of improved goods and services like Toyota or Sony.

Outsiders often feel, the Islamic world consists of different ethnic groups who believe in Islam, but it is equally so a series of warring tribes. As one political scientist said, Islamic countries are really tribes with flags. Let me give you one example.

We were sitting around the campfire one evening, when one of my adopted Bedouin brothers so-called, was talking about their tribe and in Arabic. He said, “You know, there’s no better tribe than us.” I then realized that across the Middle East, there are Afghans, Pashtuns and Berbers saying, “there’s no better tribe than us.” That is different than the individualism of democracies.

Then I went to northern Kenya to live with an indigenous, monotheistic group of Cushitic camel herders, in other words, the remnants of the Somali who had not converted to Islam, the Rendille. and that was strong fieldwork. Over a period of two years, I experienced what it means to be tribal at a deeper level. The Rendille knew about other tribes and interacted with them, but in their pre-industrial non-written, social psychological way, they lived as if they were the absolute center of the world, not the best, but the center of the world.

This was one of the things that taught me about sub-Saharan Africa and the Horn, that there are levels of tribalism, and that was a shocker. There is a neighboring tribe that I did development work with called the Turkana, and as I was working with the Turkana for six months, I had this unpleasant feeling. They were nice enough. I was an expatriate. I was there to help them do development work. I was not there as a researcher as such. I was training Kenyan researchers to do what I had done previously among the Rendille, who had adopted me. However, I realized that as far as the Turkana were concerned, if I dropped dead in front of them, no one was going to care.

Tribal Africans are not raised on universal values. They are not raised on Judeo-Christian or Abrahamic or constitutional life liberty, happiness under God values, none of that. The churches may try to change them, but they have not succeeded. When you read about all these horrible wars in the Congo what is missing is that understanding, because it is completely politically incorrect. The notion of identification with a universal “human race” or even a country, is something that came with great strife and toil.

For contemporary Americans who do not like their constitution, these experiences should make them think twice about what kind of society you get when you revert to that. The various varieties of tribalism in the Islamic and the sub-Saharan African world are a reminder of how terrible things can be and were, before the rise of representative democracy. It is not the kind of conclusions that most anthropologists entertain. That is why I believe I am the only Canadian born conservative anthropologist.

Those were my big takeaways. One of the things I say about cultural differences is that when you are in a foreign culture and language and suddenly you feel uncomfortable about something, you have hit a cultural difference, spoken or unspoken. That was the feeling that came over me living among the Turkana.

Jerry Gordon: How did you fall in with the Leakey clan and how long did you live and work with him and in what capacity?

Geoffrey Clarfield: Like you and millions of other Canadians and Americans, I grew up looking forward to reading the National Geographic Magazine that would show up at our house each month and which introduced me to the variety of the world’s places and peoples. Of course, the Leakey’s were foremost among them and very often highlighted.

When I ended up in Kenya, in Nairobi, the presence of the Leakey family, especially at The National Museum, was everywhere. People talked about them. The son, Richard who passed away, earlier this was an autodidact and very gifted. He ended up becoming the head of the National Museum. At some point, someone encouraged me to make an appointment with him.

I must say I was shaking in my boots. I had been used to famous people in show business, like I worked with Tessie O’Shea the great vaudevillian and Jackie Burroughs, the Great Canadian actress who became a close friend and mentor of me. Musicians, actors. That was okay. But science, world famous scientists that was something else. I wanted to teach Kenyans how to do cultural and social anthropology and collect traditional music and I told him that.

I wrote my first proposal for funding and managed to get an appointment with him and pitch it. I remember getting sort of tongue tied in the middle of it. He was a genuinely nice guy. He did have his dark side. He said, “Mr. Clarfield, just give it a minute, will not you … “And I managed to do it, finished the pitch. The Scandinavians funded it and the museum hired me as a consultant. Richard was my boss for just under two years until he got pulled upwards to run the Kenya Wildlife Service as wildlife poaching was rampant in Kenya.

To be fair to him, he was pulled up the ladder, it was a job that he did not want, so I had a little under two years with him once a month conferring with him at 6 o’clock in the morning. That was when he was at his best. Collaborating with, he was a good mentor. You did not want to get on his wrong side, however. It was not helpful to show that you knew too much more than he did. But other than that, it was a good run. Because he treated the National Museum a secular scientific monastery. Through him, I met a full range of scientists, and development specialists, across a wide range of fields. At that period in my thirties, I would have been specializing, and so it pulled me out of my narrow focus, and I generalized. Just after he left, I raised funds to do a strategic plan for the museum, which enabled me to understand how institutions work.

Richard believed in excellence. By contrast, Canadian culture often implicitly preaches “strive to be second best.” being under the Leakey family umbrella made me realize, “If I really work hard, the sky is the limit.” I realized that there are people out there who will recognize me for who I am, not where I came from, or who I know. The late Richard Leakey to his credit gave me that permission to strive for excellence.

Jerry Gordon: You and I share an interest in Sub-Saharan Africa. In your case, you have been to Kenya, Tanzania, Central African Republic, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. In my case, it is really associated with Somalia and more importantly with both the Republic of Sudan north and South Sudan.

Geoffrey Clarfield: Right.

Jerry Gordon: What do you attribute the underlying causes of these unstable failed states particularly in the Sahel region and the Horn of Africa.

Geoffrey Clarfield: The question of questions. First, let me preface the answer with something positive. When you look at Sub-Saharan Africa through the political lens or the economic lens, it is as you described. You could replicate that in any World Bank report. I just want to not dwell on it for the moment, as I want to highlight the fact that so much of the genius of modern music, American music, jazz, rock and roll, blues is a creation of Sub-Saharan Africans.

I could spend an hour on a musicological diversion going through the details of that argument, but it is now the musicological consensus. It was not so one hundred years ago. Similarly for the plastic arts and for dance, it is politically incorrect now to say that certain civilizations in the Nietzschean sense have an ethos.

For example, the Europeans do science well. I used to have humorous, off the record exchanges with African colleagues when they said to me, “We have to get rid of all the foreigners and your culture,” I said, “Well, am I allowed to take mathematics and philosophy back to Europe and America with me?” So, Africa is from an African musicologist’s point of view, the Holy Land. It is the source of so much genius, yet, as you rightly point out, it is a political and economic basket case.

The simple one-minute explanation, I think, is that there is a fundamental difference in Sub-Saharan Africa agriculture, the way people farm, and that of the Islamic Middle East, South Asia, and traditional Europe. Unbelievably, as one French Marxist called it, it is the ‘digging stick mode of production,” small gardens versus the plow.

What that created before colonialism and even during is, cohesive tribal societies that are live within their own social and religious universes, as I pointed out. The important thing that impressed me in northern Kenya was that these tribes are sufficient unto themselves ecologically, economically, politically, religiously, symbolically.

Then these non-literate states were confronted with modernity. It is uncomfortable and politically incorrect to say that the fundamental difference between the Islamic world and the world of India and China is that these were literate states with semi-literate and illiterate peasantries. Sub-Saharan Africa did not have a literate tradition outside of Ethiopia.

Christianity and Islam, and the jump to modernity is the fundamental diagnosis. But with respect and humility, put that explanation up as an inverted pyramid, because each level as you go up the inverted pyramid has complexity. The fundamental thing is that these were pre- agricultural, tribal groups. With exceptions, there were traditional hierarchical kingdoms like the Ashanti, but most Africans lived in tribal non-hierarchical societies, which were cut off from the rest of the world, I know there will be a million African historians who will say, “No. Colonialism, imperialism,” but I disagree.

At a fundamental level, there was a great contrast between tribal Africa and the peasant urban dynamic of advanced pre-industrial agricultural societies. Africans are suffering under that burden to this day. Eventually, it will be good because there are certain positive things in interpersonal relations among Sub-Saharan Africans that can be documented: a kind of openness and liberality between male and female, old and young, and a general joyousness,

When you sit around with people who have lived and worked in Africa and they are not being worried about being politically incorrect, these are the kinds of things they will say, a life affirming local approach to life. That is the big one as far as modernity. It is very challenging, and that goes to explaining why things are the way they are.

Jerry Gordon: How threatened is Africa by Islamic Jihad extremism?

Geoffrey Clarfield: Two sides to that question, I would say very, if we see it through the contemporary lens. Islam seems to go through waves. This goes back to a North African philosopher of history, named Ibn Khaldun with whom you are familiar. He wrote this marvelous treatise on history called The Muqaddima, which is still one of the best handbooks for understanding Islam and the Arab world. He said that, and I paraphrase, “Islam goes through periods of aggressive puritanism and syncretistic tolerance.” It looks like that from the 19th century that the presence in British, Belgians and the French in particular, triggered one of these Islamic reactions, what I like to call collective nervous breakdowns.

It is not only the Islamic world, but China has also had it; they may be going through one right now as we see the news from Shanghai, and so there is a real threat. The French are more aware of it than other countries, the Americans are conflicted about it, the Canadians, I do not think they care. The Europeans are aware of it. It is bad, it is big. Some of my Muslim colleagues say that it also must be solved internally because it is about the nature of Islam. Today the minority position within Islam is that there is a path towards modernity and living with other cultures without trying to conquer and kill them.

We must guard ourselves and hope that moderate forces within the Islamic world, whether they come from Indonesia or India, can change this kind of collective madness that is possessing the Islamic world.

Jerry Gordon: How problematic are Russia and China’s exploitation of African natural resources through these very questionable infrastructure deals. Not only infrastructure deals, but exploitation of natural resources in the case of Russia and its paramilitary Wagner Group?

Geoffrey Clarfield: Yes, the Wagner Group with their special militias, and yes, let us talk about that. The Chinese, to my knowledge, have been the biggest players and set the tune. The first thing to point out is that the West, which is Europe and North America, lost Sub-Saharan Africa. We lost it, and we may have lost it because of colonial and, or racial baggage, the whole attitude of the United States only recently, since World War II, treating blacks as functionally equal citizens, not just equal in the law, but equal functionally, made the new leaders of Sub-Saharan Africa scratch their heads and say, “Is that our model?” The British and the French had a legacy of colonialism. I am not saying that colonialism was all that bad, that is a whole other discussion.

The first thing that Africans will admit when you are speaking off camera, is the English and the French brought science, modern administration, they brought the concept of a nation state, communications, TV, the internet, and commercial and civilian transportation. They will not say that in public. The Chinese invasion of Africa occurred about 10, 20 years ago when they realized that Africa was ripe for the picking as client states of infrastructure projects and the sources of valuable natural resources for their Chinese Industrial Revolution, which is ongoing, and they came in with the One Belt, One Road projects and massive debt burden.

The odd thing about it as an anthropologist is they are so culturally distant from Africans. Chinese are not keen on Africans. I know this from personal experience. They have very dark prejudices, about Africans. From the Africans’ point of view, the Chinese and Russians may as well come from Mars, whereas they have issues with Europeans and North Americans. This appeals to the leaders of most African states. In Africa you have a hierarchy from terrible tyranny to open democracy like Botswana where you are freer to write in the papers, than you are in Canada right now, after our lovely brush with martial law. Economically this has allowed the Chinese to take over African economies,

I saw this happening. The Chinese arrived, they organized a conference, handed over checks of millions of dollars on television to the Prime Ministers and the Presidents of these countries, creating a special slush fund, called the President’s Chinese Zambian Fund or whatever President’s Fund. In turn they got enormous amount of access to ports and natural resources and built infrastructure in a situation where it is the Africans who cannot pay them back.

There may be regime change, there may be siphoning off hundreds of millions of dollars to Swiss banks, and then the poor African country after an election is left with an outstanding debt of tens of billions of dollars to the Chinese who then repossess their assets in a pernicious colonial imperial style investment. It is not even mercantilism equivalent to Hudson’s Bay in Canada or the East India Company. It is worse.

The democratic benefit that sub-Saharan Africa was supposed to get after the end of the Cold War in 1990, and which I experienced, has been squandered. I remember I had to deal with the Prime Minister of Tanzania for four years straight. A long and lovely complex story, but it was a bit of a David and Goliath metaphor.

I was running this little project in his region that he wanted to direct towards his political ends, so we had face-to-face meetings and negotiations. The first conversation found me saying to him that I am terribly impressed. Tanzania has cleaned out its ghost bureaucracy, it has opened the currency, trade is flourishing, you have political parties, you have a free press. I really rejoiced.

I was running a rural democratization project, and I really felt part of something bigger. I thought this was wonderful. I could summon up a United Nations Development Plan scenario for what they call a mid-level country where there is no starvation, people can eat and they have access to primary and secondary school, a kind of Barbados in East Africa.

Then after 9/11, the world became a different place. It got polarized and the Chinese said, “Okay, we’re going to come in.” I do not know as much about the Russians in sub-Saharan Africa, but I suspect that they are taking a page out of the Chinese playbook.

Jerry Gordon: Except in the case of Putin, he is getting access to things like naval bases in the Sudan and the Wagner Group seizing gold and uranium mines in Sudan, and the Central African Republic, supporting that Coup leader in Mali and Sudan training Islamist militias to ethnically cleanse indigenous tribes.

Geoffrey Clarfield: Chinese and the Russians, both.

Jerry Gordon: Yes.

Geoffrey Clarfield: Yes, my heart goes out to Africa, Africans. I am still in touch with friends there, colleagues who become friends. And I just feel badly for them. It hurts. It is not a good scenario. They have lost their freedom again; they have simply acquired new colonial masters.

Jerry Gordon: Right, you had talked earlier about your experience living with Bedouins, and then the area below the State of Israel.

Geoffrey Clarfield: Yes, in the Sinai.

Jerry Gordon: How would you, as an anthropologist, describe what are the fundamental features of the Arab world and then the more complex Israeli society? And how would you contrast them with what we have just been talking about, the sub-Saharan African culture and South Asia?

Geoffrey Clarfield: That’s a very challenging question, as the Rabbis would say to answer on one foot, so I will put both feet on the ground, see if I can get you there. I will start off with similarities. There is a greater similarity between India, less so Pakistan, more so Sri Lanka, less so Bangladesh, a little more so Nepal and Israel. These are Asian peoples.

The Jews are an Asian people. They have a history of literacy. They have tolerant theological world views. And if we were going to have a seminar on successful modernization, one could come to the counter-intuitive understanding that sociologically, Judaism and Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism at deep hard to explain levels are similar which allowed them to manage the transition to modernity during the 20th century.

I do not think it is an accident that India and Israel are having growing ties, it is not just geo-strategic, it is cultural. The Hindu-Buddhist tradition has zero antisemitism in it, any anti-Semitism or anti-Israeli feeling outside of, let us say Islamic Pakistan in South Asia is, unfortunately because of the influence of British and American Marxist intellectuals, it is so sad.

I once attended a lavish dinner party with my wife Mira in Hyderabad in one of the Nawab’s old homes, and these young PhDs from Delhi University, were like doing the whole Marxist mental gymnastics in their minds. One of them having just got a contract with the World Bank was paid $150,000 a year. The Jewish people and the South Asians have managed that transition because of ancient pre-adaptation.

The Muslims and the Arab world may have been able to pull that off too, but. The great Polish travel writer Ryzard Kapuscinski, and I call him an anthropologist, once wrote a chapter in a book he authored on the Shah of Iran, King of Kings. He wrote like Kafka as, you know, and he has a little paragraph which I have used in many reports called Oil is a Fairy Tale or oil is a dream.

Here is a quote:

He writes,

Oil kindles extraordinary emotions and hopes, since oil is above all, a great temptation. It is the temptation of ease, wealth, strength, fortune, power. It is filthy, foul-smelling, liquid that squirts obligingly up into the air and falls back to earth as a rustling shower of money. To discover and possess the source of oil it is feel as if, after wandering long underground, you have suddenly stumbled upon royal treasure. Not only do you become rich, but you are also visited by the mystical conviction that some higher power has looked upon you with the eye of grace and magnanimously elevated you above others electing you its favourite. Many photographs preserve the moment when the first oil spurts from the well: people jumping from joy, falling into each other’s arms, weeping.

Oil creates the illusion of a completely changed life, life without work, life for free. Oil is a resource that anesthesizes thought, blurs vision, corrupts. People from poor countries go around thinking: God, if only we had oil! The concept of oil expresses perfectly the eternal human dream of wealth achieved through lucky accidents, through a kiss of fortune and not by sweat, anguish, hard work. In this sense oil is a fairy tale and, like every fairy tale, a bit of lie. Oil fills us with such arrogance that we begin believing we can easily overcome such unyielding obstacles as time. With oil, the last Shah used to say, I will create a second America in a generation!

He never created it.

Oil though powerful, has its defect. It does not replace thinking or wisdom.

For rulers, one of its most alluring qualities, is that it strengthens authority. Oil produces great profits without pulling a lot of people to work. Oil causes few social problems because it creates neither a numerous proletariat nor a sizeable bougeousie. Thus the government, freed from the need of splitting the profits with anyone, can dispose of them according to its own ideas and desires. Look at the ministers from oil countries, how high they hold their heads, what a sense of power they have, they, the lords of energy, who decide whether we will be driving cars tomorrow or walking.

And oil’s relation to the mosque? What vigor, glory, and significance this new wealth has given to its religion, Islam, which is enjoying a period of accelerated expansion and attracting new crowds of the faithful.

The minute you get oil in great quantities, you don’t have to work, you don’t have to save, it’s just a pipe of money and basically implies that the Iranians and the Arab world largely, with some exceptions like Morocco and Egypt, their modernity was crippled by all this free money and all this free oil and the power that went with it.

I will then go back to the earlier points about the differences between traditional agriculture and traditional digging stick mode or horticulture, and say that despite the incredible amount of turbulence, violence, and militarization that the Arab world has had, the Sub-Saharan African world was at a disadvantage because they did not have a literate culture, they did not have an elite.

In the back of my mind, right now that there’s greater freedom of press in Kenya and Tanzania, and even South Africa, which is a very conflicted place, than in the Dominion of Canada, and there’s hope for Sub-Saharan Africa, because I think culturally, part of that tribalism allows for a flexibility. I have said this to friends who asked me, how do elite Africans, let us say with PhDs perceive their history in the West?

Well, the first thing that they must deal with, is a history of people saying, “Your language is wrong, your religion is wrong, your agriculture is wrong, your politics are wrong”. Now, when someone is telling you everything about you is wrong, it sounds like the experience of the Jews.

You can cherry pick, you can take this, you can take that, from a sociological point of view, a certain amount of consistent persecution is liberating. Consider a place like Botswana which had enormous diamonds and could have become a basket case and they spent it on social services, it is not their fault that the AIDs epidemic started in Congo. We had Covid in 2019. Botswana, Ghana is Tanzania and Kenya, although they have difficulties, are not bad places to be. If things get bad here in Canada, I have said to my wife and kids, we got used to living in Kenya and Tanzania, we can always go back. At least they have relative freedom of the press.

Jerry Gordon: When you came back to North America, you dove into your ethnomusic background. You went to Manhattan, and you worked with the Alan Lomax music archive in New York City. So, what was that experience like professionally, and what did you think of New York and New Yorkers?

Geoffrey Clarfield: First, I like New York, and I like New Yorkers, I like New Yorkers better than I like New York, but I will come back to that. At an earlier stage in life, I hoped that I would make a living as a musician, become a professor of Ethnomusicology. However, as I pointed out before, I rightly recognized that affirmative action was not going to work in my favor, so I turned musicology and ethnomusicology into an avocation. I tried to keep up with the literature, maintained several active musical projects which are ongoing, and came to the attention of Alan Lomax’s daughter, Anna Lomax, who is a PhD and an expert in Italian folklore and a Knight of the Italian Government. She followed in her father’s footsteps doing musical development, what they call cultural equity. The word equity has lost its past meaning of fairness, but they had it 20 years ago, meaning a kind of toleration and encouragement of diverse musical traditions.

Alan was world famous because he discovered Muddy Waters, he was a friend of Pete Seeger, he looked at the poorest of the poor among whites, Black people, and Hispanics, and really changed the way Americans and the world listens to music and worked out various models of community development and ethnomusicology.

When I ran into Anna, she saw that I had this development experience, how to move an NGO forward, the details of understanding Ethnomusicology and American music, which I love dearly. Part of my professional experience has been how to learn how to write good proposals and raise funds. All these organizations were not good at fundraising, and I said, “Well, I can help you raise funds, and I can help you strategically plan your NGO, your non-governmental organization.”

I understand the content, because as you know, from your own experience that bringing in a management consultant to a company without deep knowledge of the content is often a total waste of money and a managerial disaster. I had done my research and worked at the museum in collections and the Lomax Archives gave me a contract for three years. I lived on the upper West Side, I rode my bike down the Hudson River every day for seven months a year, and back up. Because it is a well-known music archive, Lomax was a remarkable American He was a mentor of Bob Dylan, and others to put it mildly.

All doors were open. “Oh my God, you’re the Director of Research and Development on The Lomax Archive, let’s open the door.” I got a privileged access to that world, I found New Yorkers full of life. There is the famous New York minute that I had to learn to deal with, because as a Canadian, I always thought I had 30 minutes to respond, where I really had 30 seconds. I had to learn that things happen quickly. I also learned, and this comes from my brother who did a sabbatical in New York, he said, “New York’s a city of finalists. New York’s a city of people who are excellent at what they do, whether it’s ballet or music, or finance, or research or museums.”

I would go to the Met Friday afternoon because everyone was gone, so from 5:00 to 8:00, I had the Metropolitan Museum of Art to myself, and I could go there endlessly. The number of museums, the number of free concerts, the number of bookstores … my favorite bookstore in the world is the Strand. That is where I discovered Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean.

Jerry Gordon: I believe that as both Jean and I worked in New York and partook of its magnificent smorgasbord of cultural offerings.

Geoffrey Clarfield: I felt invigorated by New York. I had to live up to its historical reputation, I had to be a player, a winner. I got two National Endowments for the Arts grants for the Lomax Archive, which I am very proud of to this day, whether one thinks the NAA has gone the right way or the wrong way. Anna and her colleagues were first rate. These were well-educated thinking people, they tended to vote Democratic, but that would be unfair to say that they were like the squad or extreme progressives. These are thinking, reasonable people who want the best for themselves and the United States, and the world, especially the developing world.

New York, I was supposed to be there. Here is my line. When people said, “Oh, Mr. Clarfield, what brought you to New York?” I said, “Well, when I was thirteen, I auditioned for the children’s chorus of the British musical, Oliver, and I got in and I was supposed to spend age 13-16 in Manhattan, but my parents nixed it. So, it took me a few decades to get there.”

New York is a mess right now, but it is resilient, and I really hope it will bounce back, when they will get the right Mayor. Sometimes you must go through purgatory to get to heaven, I guess.

Jerry Gordon: Speaking of purgatory, I would like to turn to your home ground in Canada and which I know well.

Being a weekly commuter to Toronto for two years, resurrecting and selling off a cross border insurance holding company I got to know what Canada was about. Every time I would come back on the weekends to hug my great wife Jean, friends of mine would ask me, “Well, how are our Canadian cousins?” And I said, “Hold on. You do not understand what their ethos is. It is etched in granite on their Articles of Confederation. They believe in “peace, order, and good government.” And that is not exactly what is in the US Declaration of Independence: “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Geoffrey Clarfield: No.

Jerry Gordon: What was your experience with that, growing up and being educated in Canada?

Geoffrey Clarfield: I could answer that in so many ways, but I am going to go with my intuition. The first thing I discovered living overseas for a long time was that one way of defining Canada was that part of British North America that decided not to rebel and not put personal liberty at the top of its political agenda. What follows from that? Well, “peace, order, and good government.”

What really followed from that was sleep-walking British-style democracy. As my late father would remind me, until 1945, Canadians first thought of themselves as citizens or subjects of Britain. They may have been Canadian citizens after 1929 but they were subjects of Britain. They had the homeland, whether they were immigrants from Poland or Ukraine, it did not really matter.

That was the home ground, which was the level of excellence that you were supposed to aspire to. It was very popular when I was young and in the ’50s and ’60s for young Torontonians would go to Oxford and Cambridge and come back with a British upper-class accent that they never lost. One of Canada’s greatest novelists, Robertson Davies did this, I thought he was born in Britain, then I found out that he had done that. I still love his novels.

There was 100 years of being fake English men. Now, not fake in the real sense, but in the anthropological sense, is that you were trying to be someone else and culture that lived overseas, and the language had even changed, the accents had changed. But politically, the Queen still bound you. There was the notion that the Queen or the King had the authority of the state. There was the tradition of British law, of common law, of precedent in the courts, and of course, the unspoken question, Quebec. On the Plains of Abraham, when General Wolfe and Montcalm were fighting it out…the French lost.

The British conquered, Quebec, New France, and in their enlightened toleration did not force them to convert to Protestantism like they tried to do in Ireland, and which Edmund Burke, got so worked up about, but tolerated and encouraged them and left them alone and said, “You can have your Catholic Church, you can have your medieval society, you can have your Purists, you can have your Napoleonic Code, which they still have in Quebec. And we’ll get on with doing what we do because we’re part of the British Empire and we rule the world.” So, the Quebecois were downtrodden. If you look at a Quebec license plate, it says, “Je me souviens“, I remember.

What do they remember? They remember the conquest, in other words. It is the injustice of being conquered is in their license plate, the resentment is so deep. And after World War II, when they had their own quiet revolution, everyone started getting secular, that Catholicism became French Quebecois, whatever you want to call it, nationalism and occasionally, they would flex their muscles and say, “We can live just like the Yanks did. There’s nothing stopping us.”

There is even as you know, something in the Declaration of Independence or The Constitution, I am not sure, a clause which says any Canadian province can join. Gee, they did not teach that to us in school or university. So, there was this imitation British style democracy where you are free but not as free as in the United States. And along came a son of Quebec, influenced by Rousseau and French ideas and Marxism. The women loved him, he was handsome, he was like a musketeer, Pierre Elliott Trudeau. And because you must carry the Quebec vote, he became the Prime Minister, and he decided to rebuild Canada in the image of Rousseau/Marx. And lord it over with his brilliant Harvard-trained Cartesian mind to trick what is called ROC-the rest of Canada.

The rest of Canada and “Les Anglaise,” the English, who they have detested and create this top-down Charter of Human Rights, which was similar to the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. Except that for 40 years, if you’re an expert and there’re greater legal experts, than I like Bruce Pardy at Queen’s University who’ve been tracking this stuff. No one’s paid attention.

It is as useless, I have to say, as one of these constitutions of revolutionary African states, where all men are free except the President is above the law. And this has eroded the legal rights of Canadian citizens for the last 40 years until it culminated, and Jerry, I am still reeling from it physically. I felt it physically when they declared martial law, because they were upset at the very peaceful protest of the Canadian truckers.

Trudeau the younger, ran away, went off in seclusion like there is a revolution in the offing. They turned the police on them, it was very unfortunate and sometimes violent. They vilified them, they scapegoated them. There was one liberal MP, they had a slogan, HH Honk Honk in support of the truckers, and she got up in Parliament and said, “It really means ‘Heil, Hitler’,” demonizing, threatening.

Those emergency laws are now being made permanent, so Bill 100, which is provincial from the provincial Conservatives. You can hear me getting a little emotional. I am sorry. I am not sure if it is passed or it may just be in the process of passing, which allows the government to seize your bank accounts, your business, and your money without habeas corpus, without a court order.

There is that old joke about Ho Chi Minh, when he is asked whether the French Revolution was worthwhile, and he says, “It’s too early to tell.” Well, I do not think it is too early to tell that British style parliamentary democracy has failed in Canada, it is dead. The government now has all these powers which used to be the defining features of non-democratic governments. That is where we are right now. There is very little push back.

Jerry Gordon: Which is strange to me because I had respect for the Conservatives, both in Parliament as an opposition, but also when they held the reins of government. I can cite the experience I had in the late ’80s with Brian Mulroney, who was from Quebec. And very interestingly with Stephen Harper who came from kind of revisionist conservative background, the so-called Prairie populism of Canada. What was so refreshing about that was the fact that he held Israel in high esteem, and that is not the case anymore. Why is that?

Geoffrey Clarfield: There is a consensus among right-minded people. God, that sounds like Obama, doesn’t it? That when a Democratic country, whether they are in Latvia or Western Europe or North America, is recognizing the rights of its citizens as individuals given certain rights by God, then the external politics is more sympathetic to Israel. It has nothing to do with what Israel does or does not do. It is the dynamic of ethical monotheism, which is at the basis of modern representative democracy or so I would like to think.

Harper wanted the most freedom for Canadians, he wanted individual rights, he wanted entrepreneurial citizens, he wanted good relations with NATO, and it was natural therefore to support Israel. For better or for worse, the State of Israel is often a symbol for people in Western democracy sharing that Judeo-Christian tradition of righteousness and the Ten Commandments. I can put it in Texan terms, and when you move against that, you are going to move against this… I think what Jung would call it a deep-rooted archetype, you are going to go on to the dark side of the forest, as they say in popular culture. Steven Harper is a very good man, and I think like Reagan.

Those dynamics play out in that way, so those are my initial responses to that. And when anyone who turns towards anything Marxist with a basis in the French thinker Rousseau, there is a correlation, they become more anti-Israel, they become more anti-American, like the Iranians, with their religious version of the general will, through a group of elite priests, death to the great Satan, death to little Satan. I must say from an Israeli point of view, I always feel great when they call out death to the big Satan and the little Satan that finally plucky little Israel is a player. Until 1945, Jews were just a tolerated and persecuted minority around the world. That is progress.

Jerry Gordon: I would like to talk about this horrible word, which now is a doctrine that has encapsulated the minds of a whole generation, the millennials in this country, it is called wokeism. But first, gives us your sense of how bad that is in Canada and to a degree, how much of a threat it is here in the US?

Geoffrey Clarfield: The quick answer is that it is terrible, and it is everywhere. It is in the media, it is in the schools, it is on the street, it is in the institutions. If it did not originate in Canada, it was test-driven in Canada.

Part of the Trudeau elder revolution was the embracing of Marxist thoughts. When I was at university here in 1972 to 1976 and then later graduate school, Marxism was creeping in from all sides. It was just one of several world views, but it was aggressive.

Now, for example, in my field of anthropology, Marxism, radical feminism, wokeism, indigenous ism, whatever it is called has completely dominated the field, there are very few people doing serious work. Part of it was driven by a deep unconscious anti-Americanism. Sadly enough, and this is something that I could have only articulated recently after martial law here, is if you choose a path which does not include universal morality, eventually you are going to distance yourself and embrace the opposite of universal morality which is tyranny, and the various justifications of it. I will start the lineage. It starts with Rousseau, it goes to Marx, radical Marxism, then radical feminism and now got racialized with wokeism.

Radical identity politics is now upon us. The goal at the beginning was that America and less so Canada, Britain, and France, France closer to America, is there is a natural culture to assimilate. Eric Zemmour in France is the most outspoken example, but it does not mean he’s not Jewish, it does not mean he does not support Israel, but he supports what they called the secular nature of the state. And so, I have watched with horror and depression as wokeism is taking over Canada.

And to demonstrate that I was not looking at this with a prejudicial eye, I read, it was three hundred or four hundred pages of the Toronto District School Board, humanities, high school guidance document, in other words, what the teachers are supposed to be instructing their students, and it was completely woke. There were forty-four mentions of equity, and I do not think there was one mention of equality. I authored a little article about this; I think for American Thinker or The Epoch Times. And I have also noticed that among friends who I grew up with or study here who are, I guess as you would say in the States on the left, or part of wokeism I am walking on eggshells.

I still have a few of them as friends. When we have a dinner party, what do we talk about? Restaurants, family stuff, travel, we can barely talk about literature or television because so much of it has gone woke. I cannot talk to them about identity politics because they are guilty because they feel white.

And I do want to point out that in Canada, the only opposition media outfit that is not subsidized by the government, Americans are not aware of this, is Rebel Media under Ezra Levant, and Trudeau the younger just denied him and his outfit a journalism permit!

Now, this is so 1984, and this is Brave New World. In other words, all the journalists are publicly on the take, they are all getting subsidies. The National Post that I used to write for regularly is now getting thousands of dollars from the state, to so-called create independent Canadian voices. They are dependent. The one outfit who has the courage, because they really get harassed, to stand up to the government in the old newspaper style, is denied accreditation. The government says you are not real journalists. As George Orwell wrote “Love is hated, truth is falsehood.”

It makes me want to cry. And the last point, Jerry, is that there is pushback here and there, but it is not massive. I believe in the United States, there is a Manichean struggle between good and evil going on, and the forces are, sadly enough, equally poised and positioned. But at least, there is a struggle going on. Here, the fight is over.

Jerry Gordon: I would like to end this fascinating discussion with questions about a place you know very well, and that is Israel.

Geoffrey Clarfield: I am married to an Israeli, we are all both Canadians and Israelis, my wife and our two sons. I spent many years working and living there.

Jerry Gordon: So recently, the former Israeli Ambassador to Washington or the US, Michael Oren, who himself was an Oleh from New Jersey here in the US…

Geoffrey Clarfield: Right.

Jerry Gordon: What about Israel’s democracy and sovereignty problems? What are they, and do you concur with his observations?

Geoffrey Clarfield: Michael Oren is right, his recent interviews, and writings point out two shocking truths, that the Jewish people and Israelis, although they have had 70 years of independence, are not particularly good at sovereignty, and they are not very good at democracy. And what he means by that, I think is liberal democracy.

The voting polls in Israel, I do not think are as rigged as they are elsewhere. I know that may get me into hot water with those on the left. Bernard Lewis, the late great British historian of Islam said, I think in one of his books, what is going wrong or the problem of Islam and modernity, said in a throwaway line something like this. “The demographic majority of Israel, contrary to Leftist Marxist stereotypes that they are all white men who came from Europe somehow, are from the Middle East. “The average Israeli citizen, I think at least 60%, came from North Africa to Iran. And they were under the authoritarian rule of Muslim cultures and societies. That rubs off, and they brought that authroitarianism to a country where a minority of democracy loving Ashkenazi revolutionaries were trying to create liberal democracy. So those… ideas of democracy and the practicalities of it are colliding there.

Very often, you really do not get what you vote for. Bennet and recently Prime Minister Bennet has a handful of seats in the parliament. In what country does a guy with a few seats out of 120 Parliamentary seats get to rule? I do not know. So, there are structural issues and there are cultural issues.

The other thing is about sovereignty, and here is where I am going to sound like a voice in the wilderness, and I am always saying to other Jewish people. There is a real tried and trusted trope, you got to watch out about that, because it verges into know-it-all-ism, or it can, is who are the Palestinians? I call them the Arabs of the Land of Israel and that is an interview in and of itself as to why.

There are fundamental points I want to make, and that is that the Mandate for Palestine included what is now a large part of Jordan, the East Bank, there is no such thing as a Jordanian people. Let me be an anthropologist and say definitively, there is no Jordanian ethnic group. And let me jump to being an existential gestalt anthropologist, that most people in Jordan say they are Palestinians in occupied Eastern Palestine. Oh my God, what a gift to the Jews and Israelis, except they do not take it.

We have this fictive State of Jordan, which is really a Palestinian state, a state of Palestinians, legally, ethnically dominated by, as one Jordanian opposition member said, by an apartheid regime of Bedouin from Arabia, called the Hashemites. From a pragmatic point of view, the Israelis have put up with that lie for one hundred years, the lie of Jordan. But the thing about a big lie, as Hitler’s propaganda minster Goebbels said, “if you repeat it often enough, people will believe it.”

So, the notion that no one’s willing to say other than the Jordanian opposition, Jordan is a Palestinian State in the historic territory of the Land of Israel, and if you want a just equitable solution between the two peoples, Israelis better wake up. This is a Muslim Arab Jordanian Palestinian saying this, not someone on the far-right. If that is even fair, and I do not think it is.

So, I despair, although I have not lost hope that the truthful history of the land of Israel is being ignored… Go to The Maccabees, the New Testament. Jesus and his disciples are walking all over the Holy Land. Half of it is in Jordan, what we now call Jordan. There never was Jordan.

Until Israelis wake up to the fact that Jordan is the Palestinian state, and a deal must be made with repatriation of population and funding by the World Bank. This is what Mudar Zahran is saying, this man that I refer to from the exiled Jordanian opposition. When someone discusses compensated emigration to Jordan of Arabs in Judea and Samaria, the exiled head of the Jordanian opposition answered the following question,” Well, can’t the World Bank pay for this?”

He said, “No, the Arab world can pay for it. We have enough money. We have oil money.” And I thought, God, there should be more Jews and Israelis who speak like that. So that is my two cents, Jerry, on the future of Israel, geopolitically. Internally, it is slightly different.

Jerry Gordon: It is interesting that I share those views with you.

Geoffrey Clarfield: That’s nice.

Jerry Gordon: I have interviewed Mudar Zahran and a leader of that movement, and Aryeh Eldad who was very much promoting that. Quite frankly, there is a lot of arable land over there, there are undeveloped resources that could support a significant population base and it would become from a geopolitical security vantage point, a buffer state against some dangerous elements in the Arab Islamist and the Iranian world. Why it has not been furthered by the right in Israel, to a certain extent is truly beyond me now.

Geoffrey Clarfield: Yes, it is a gift that we do not take.

Jerry Gordon: Be that as it may, I would like to get your opinion about how significant the Abraham Accords are in normalizing not only relations with the Emirates or the Saudis, potentially, with the Moroccans. I put the Sudanese in a different basket because they are corrupt, bad actors, but how would you evaluate that in the context of changing the narrative that you just talked about?

Geoffrey Clarfield: It is a great question, and it triggers the anthropologist in me. If you have ever read those handbooks from the Cross-Cultural Institute, I hope I have it right, of how to do business in the Arab world, the first rule is making friends. You have to feast with them, you have to get to know their family, you have to go to the beach with them, you have to hang out, you have to ride camels, you have to do whatever it takes, drink coffee, eat rice, get to know each other, almost like family, and then you do business.

Now because of the three no’s in the past of the Arab league: No negotiation, no peace and no recognition… that has prevented Israelis from getting to know Arabs outside of Arab-Israelis, and this is a great and wonderful opportunity because it goes back to the earlier point we were discussing, that most Israelis come from the Arab world, many of them are still bilingual, many young Israelis, even I know many from my own extended family whose ancestors go back to the Ukraine and Poland, study Arabic as a second language. And there is a common Mediterranean way of interacting.

Interrupting, being loud, these are not criticisms these are cultural differences that allow, that give Israelis privileged access to a better interaction with people in the Gulf States. And another thing is that Jews and Judaism like Islam have never looked down on business. We think business and the creation of wealth is a good deed. This is one of the great challenges in the Christian tradition, that there’s great ambivalence about money, wealth, and less so work among the Protestants, but they still have their issues. Among Muslims and Jews, it is not an issue. Let us get together and do business. You may have remembered, Jerry, that wonderful film, Ben-Hur, where Judah Ben-Hur meets this Arab horse dealer.

Jerry Gordon: It is a classic sequence in the movie.

Geoffrey Clarfield: And the Arab says to Judah Ben-Hur, “You know, we Arabs and you Jews, we should get together, we could do a lot of great stuff together.” [chuckle] So that day has finally come, it takes two to tango. The Gulf Arabs, I hope may be the point of entry for an interest group or a lobby, which I do not think can be based in Israel but may be able to collaborate with people like Aryeh Eldad who I had the privilege of meeting, at least just to shake his hand a few years ago.

That would be to re-establish the true narrative of the two-state solution, which is 100 years old and has been lied about, so that whoever calls himself a Palestinian (An Arab who came to the land of Israel as immigrant or conqueror) regardless of the validity of that historically or ethnically, has their own homeland. The Jews have their own homeland, and this flash point will not be an opportunity for Russians and Chinese and Europeans and Americans and every other meddler to project their own agendas on this potentially explosive part of the world. I want Israel to be less in the news and the Middle East to be less in the news in the next 100 years. That is my simple answer.

Jerry Gordon: You worked in Israel in the ’80s and ’90s. And as you said before, you have dual citizenship as a Canadian and an Israeli. What is your take on the future for Israel nationally and regionally?

Geoffrey Clarfield: Regionally, it is about finding allies, security, but nationally, I think Israelis themselves have lost touch with the history of the last one hundred years. A significant minority of Israelis believe that the Palestinians are this poor Arab minority without a homeland, that they happen to occupy, and that is the word the enemies use, out of historical necessity.

Like, “Oh, I fell out of a burning house onto somebody else’s house.” The challenge of Israel is to remind people that the Mandate for Palestine is still part of international law, it is their birth right, it is their modern, legal birth right. It is their title deed. They are owners not occupiers. They must rediscover it, and once they have rediscovered it, they can share it and make it part of their diplomatic initiative, which I am repeating for emphasis…

This argument or lobby may not come from within Israel, it may have to come from outside. I think it may have to come from United States, and it may have to come from like-minded people in politics, economics, and business in the United States, who are able to be the great peacemakers of which only President Trump and the Republican Party showed themselves capable of doing, with the Abraham Accords. The Abraham Accords is a line of credit for the Jewish people and the people of Israel to use and invest in, so that it will pay dividends all around.

Jerry Gordon: With that, I want to bring to close a fine discussion, and compliment you on being multi-faceted and multi-talented and having an acute observation of what’s trending in this world that could become a reality. That is a redeeming feature for your family, my family, and for that matter, for all Jews anywhere, but especially our brethren in Israel today. So, for that, I appreciate your availability to hold this important discussion.

Geoffrey Clarfield: I’d like to thank you, but I’d also like to emphasize that writing for and participating in The New English Review where you are an editor, has kept me sane, because it has reminded me over the last 15 years, that there are other people who do not necessarily agree with everything I do or say, but who are like-minded, and in these turbulent and troubled times up here north of the border, that is kind of guiding light, which I’ve been very grateful for. And as an editor of The New English Review, I thank you for this conversation, Jerry.

Jerry Gordon: All right, thanks also go to our mutual colleague, Rebecca Bynum, for establishing this monthly journal and blog of culture and politics.

Geoffrey Clarfield: Yes. Four cheers for Rebecca. Thanks very much Jerry. Good-bye, and thanks for holding this discussion.

Jerry Gordon: Bye, Geoffrey

Geoffrey Clarfield: Bye.

Jerry Gordon is a Senior Editor of The New English Review, author of The West Speaks, NERPress, 2012 and co-author of Jihad in Sudan: Caliphate Threatens Africa and the World, JAD Press, 2017. From 2016 to 2020, he was producer and co-host of Israel News Talk Radio-Beyond the Matrix.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast