by David Solway (April 2020)

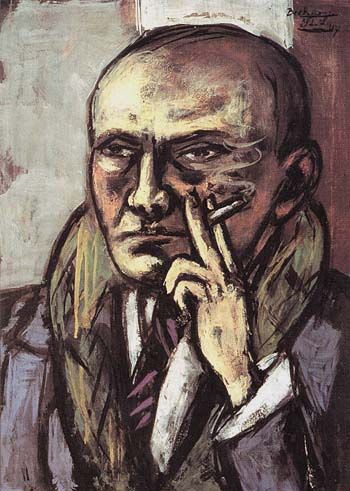

Self Portrait with Cigarette, Max Beckmann, 1947

Why do we smoke? Some people consider it merely a habit that has become homeopathic, a pleasurable remedy for a depressing world no different in principle from drinking alcohol, taking painkillers or eating chocolate. It is a fix whose only cure is a lifetime of cold turkey garnished with the rhetoric of moral repudiation. One “swears off” the thing. As for instance, teetotalers who wore badges of purity—“blue-ribbon stalwarts,” as John Buchan called them in The 39 Steps—and reformed junkies who appear on talk shows like so many Lazaruses recounting the horrors of Sheol.

And there’s the rub. We have come to equate health with morality. That is one reason, argues Dennis Prager, “the government airbrushes cigarettes out of pictures of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and other famous Americans.” The fact is that decent people and benefactors of mankind have been known to smoke. Winston Churchill puffed on a cigar; this did not prevent him from first warning and then rallying Britain against the Nazis. Thomas Mann’s cigar surely contributed to the composition of The Magic Mountain. C.S. Lewis cherished his pipe, yet he was an exemplary Christian. Bertrand Russell’s pipe was a well-known philosophical adjunct.

And there’s the rub. We have come to equate health with morality. That is one reason, argues Dennis Prager, “the government airbrushes cigarettes out of pictures of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and other famous Americans.” The fact is that decent people and benefactors of mankind have been known to smoke. Winston Churchill puffed on a cigar; this did not prevent him from first warning and then rallying Britain against the Nazis. Thomas Mann’s cigar surely contributed to the composition of The Magic Mountain. C.S. Lewis cherished his pipe, yet he was an exemplary Christian. Bertrand Russell’s pipe was a well-known philosophical adjunct.

Anti-smoking crusaders fail to understand that there are many far worse addictions than smoking, of which political correctness, the ne plus ultra of cultural hypocrisy, is the granddaddy of them all. The anti-smoking campaign is merely another sign of the holier-than-thou mentality that has gripped the culture. CEOs of companies that market hydrogenated oils and nitrates, environmental polluters like pipeline protestors leaving mountains of trash in their wake and super-rich atmosphere-befoulers flying private jets to forums that preach carbon neutrality, transgender advocates administering unsafe Lupron hormone blockers to children, Sanctuary-mongers importing filth, disease and criminal violence into their cities, and worse may never allow a cigarette or any smoking implement to touch their lips—or anyone else’s. Even a relatively innocuous absurdity like vaping—whose reported ill-effects are now linked to black-market cartridges—has come in for public opprobrium, amounting to a new form of hysteria. Of course, smoking cannabis is both legal and unobjectionable, mind-meld notwithstanding.

Read more in New English Review:

• On the Beach, On the Balcony

• For Tomorrow We Die

• The Archaeology of Living Rooms

Deluded by any number of unsustainable sanctities and conventional bromides, those who take a moral stand against smoking are among the ostentatious puritans of our time. Indeed, antismoking is one of the central shibboleths of the age, signs and warnings appearing everywhere in our public spaces. On the door of a Second Cup I occasionally frequent, I am instructed not to light up within twenty feet of the building. By the curb, not twenty feet away from the premises, a municipal bus stopping for passengers belches thick, voluminous clouds of blue exhaust likely comprising the output of thirty or forty thousand cigarettes. Customers sitting on the patio inhale the poisonous fumes with complete equanimity, but wouldn’t be caught dead enjoying a smoke with their afternoon latte.

Our anti-smoking zealots are not only marvelously inconsistent, they are also intensely self-righteous, contemporary Savonarolas. One notes that smokers who have newly kicked the habit infallibly count the number of days since they last fondled a cigarette, like sinners recalling the moment of redemption. They can never refuse the offer of a cigarette without delivering a sermon on the evils of inhalation or uttering homiletic pieties or painting lurid pictures of lung pigmentation. The whole affair has the gravity of a religious experience or an exorcism.

Indeed, as my good friend the Reverend Jules Gomes wittily writes, one of the canonical sins in the secular religion of the Progressivist/Left is smoking. “It’s not that the Left regarded consuming tobacco as particularly injurious to health (if such were the case, the Left would rail against gay sex, transgender genital mutilation and puberty blockers and promiscuity leading to sexually transmitted diseases). Smoking was declared immoral and placed on the Index of Iniquities. Since the war against smoking began, anyone holding a fag, cigar or pipe has to shout ‘Unclean! Unclean!’ like the lepers in Ben-Hur. They are cast into outer darkness where they shiver and await conversion therapy in the form of Nicorette.” Well said, Jules.

True, many people consider smoking not as an ethical lapse or a spiritual transgression but merely as a function of nerves. We must, after all, do something with our hands. Thumb-twiddling and knuckle-cracking are usually offensive in polite society. Rolling Kleenex tissues into little balls in the pockets of one’s jacket tends to make one appear absent-minded and even bored. Biting one’s nails invites the stigma of retardation. On this interpretation, smoking disguises the peculiar vulnerability of the unengaged extremities.

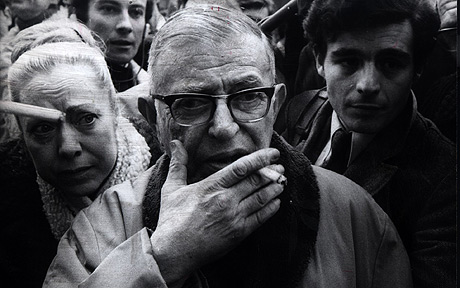

Jean-Paul Sartre, an inveterate puffer, says somewhere that smoking is an act of existential greed. It is our way of “taking in” the world, mastering it, making it ours—a form of pulmonary capitalism. On reflection it seems to me that breathing would accomplish the task quite as well, but we’ll give Sartre a pass.

Jean-Paul Sartre, an inveterate puffer, says somewhere that smoking is an act of existential greed. It is our way of “taking in” the world, mastering it, making it ours—a form of pulmonary capitalism. On reflection it seems to me that breathing would accomplish the task quite as well, but we’ll give Sartre a pass.

As most sane people recognize, smoking is not a product of moral corruption or demonic possession. Habit, nerves or greed are rather more sensible explanations. But there is a fourth possibility. Smoking is one of the most effective antidotes humankind has devised for self-consciousness, by which I mean something different from nerves. The latter is unmeditated, a spontaneous malaise, something on the level of reflex. The former involves the conscious, lucid, painful awareness of the precariousness of the things we consider desirable, numinous or expedient, the interfering clumsiness of the self that deforms and mutilates simply by drawing attention to itself.

For example. In a seduction which starts out as a dinner engagement there are those synaptic moments, cracks in the façade, in which the real motive becomes disconcertingly obvious. So one lights a cigarette and studies the convolutions of the smoke. This is the kind of social deflection—now no longer goal-directed but other-directed—that lightens, distracts or displaces the attention and thus enables the seducer to pass himself off as more or other than merely seducer. He is also interested in the taste of the cigarette or in performing an act which has nothing to do with the immediate issue. There is an entire art of elegant nonchalance or philosophic disinterestedness compressed in the simple gesture of lighting up. But the method is effective. Cigarette smoke softens the collisions of the eye and screens us from Truth’s blunt and often indelicate pursuit, in a way like dimming the light in the boudoir. It rescues us in our self-encounter with the starkly embarrassing obvious.

But even more innocent or less emotionally charged occasions require buffering. Consider a gathering of friends who have met to discuss or gossip about anything at all. The event must take place, as it were, inadvertently: it must appear extemporaneous, the expression of the moment, off-handed, improvised, if the atmosphere is not to become oppressively solemn and even chillingly official. Smoking is one of the modes of burning off earnestness. Should one of those present say to another, “Tell us a joke so we can laugh”—the universally recognized purpose of joke-telling—the one so designated finds his enthusiasm dissipating in stammers and throat-clearings. After a convivial supper my mother usually commented, “We’re having such a good time, aren’t we?” and the table froze. Or if two friends meet and agree explicitly, “We are here to talk. Let’s begin,” silence is the inevitable result.

As Walker Percy puckishly explains in Lost in the Cosmos, “by modifying certain neurones in its central nervous system,” an organism responds “to certain signals in its environment by a behavior oriented toward other segments of the environment.” Lighting a cigarette, cigar or pipe is a way of pretending that we have met for other purposes, that is to say, we have met to smoke together while in between puffs we may, as it happens, get a little conversation in. When things get too close to the bone we exhale and stare briefly to the left. And when the essential fatuity of all our works and days becomes distressingly evident in those embarrassing intervals we are all familiar with, we light up a Lucky, shunting awareness aside with an akimbo elbow as we raise the match. Smoking allows one, so to speak, to be the designated drinker.

In Confessions of an English Opium Eater, Thomas de Quincy develops an analogous argument, recommending the dinner table as the right place to pursue an intellectual conversation or a flight of eloquence. If it so transpires, as it often does, that one’s inspiration suddenly flags, one can ward off embarrassment by passing the salt or inquiring solicitously if one’s interlocutor would not like a little more wine. Since in our time we are generally less fluent and erudite than our noble ancestors, we need considerably more help limping along in our table talk. Smoking is thus an excellent dialogic prosthesis.

Then there are those for whom pleasure, or the freedom to choose one’s pleasures, trumps considerations of prudence or a fearful parsimony of indulgence. Je fume, et alors? asked French author Jean-Jacques Brochier in his book of that title. I smoke, and so? It may have cost him his life, but he did as he pleased. As he argued with his Gallic mix of flair and earnestness, “retomber dans le carcan [straitjacket] d’un moralisme écoeurant [nauseating moralism]” takes the savor out of existence. For Brochier, at any rate, no matter how high the price, “La defense du principe de plaisir est un imperatif categorique.”

Read more in New English Review:

• Weaponized Words

• An Esoteric Take on The Big Lebowski

• COVID-19, Iran, and the Middle East

• The Coronavirus Calamity: Shutdown. Reboot!

But the essence of the matter has to do with self-consciousness and untoward awareness. When one sets about writing an essay on smoking, half a pack scumbles the glare of the blank, accusatory page. There are, of course, other techniques of necessary evasion, especially as relates to creative endeavor. Oblivious to the risk of neutropenia, German philosopher and playwright Friederich Schiller kept a drawer full of rotting apples, which he sniffed when inspiration faltered. Gustave Flaubert relied on his lover’s mittens and slippers, which no doubt assisted him in the composition of Madame Bovary. But smoking may be regarded as one of the most potent of parrying tactics at our disposal, deflecting attention from the task at hand when it seems unmanageable, and indispensable insofar as it helps us keep up the illusion of the unpremeditated nature of our schemes and aspirations.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

David Solway’s latest book is Notes from a Derelict Culture, Black House Publishing, 2019, London. A CD of his original songs, Partial to Cain, appeared in 2019.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast