by James Stevens Curl (October 2019)

Seagram Building (Philip Johnson and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe), NYC

This review was originally published in The Jackdaw: Independent Views on the Visual Arts 147 (September/October 2019). It is reprinted here with permission.

Philip Cortelyou Johnson (1906-2005), born with a silver spoon in every orifice, was an American architect with an aloof disdain, probably fully justified, for the opinions of the masses, given their propensities to vote for nullities or worse. With his independence of mind and very considerable wealth (bestowed on him by his father), his flair for publicity, and his political skills, he established for himself a powerful position in the architectural world, both as an architect and a taste-former, not unconnected with his eminence in the gay milieu he fetchingly adorned for so many years.

During his time studying philosophy at Harvard, he met Alfred Hamilton Barr (1902-81), who pointed him towards an architectural career. Barr, with others, created, from 1928, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), NYC, and was Director of that establishment (1929-67). It was Barr who called in several young men to assist: Johnson was one of them, and Barr asked him first to travel to Europe to learn about trends in modern architecture. Joining forces with the gay and malodorous architectural critic and historian, Henry-Russell Hitchcock (1903-87), Johnson met leading members of the European architectural avant-garde, including Ludwig Miës van der Rohe (1886-1969), who only a few years earlier had added both the diæresis to ‘Mies’ (which has connotations in German with what is seedy, wretched, and out of sorts) and ‘van der Rohe,’ which sounds vaguely grand as well as reassuringly Dutch, with a touch of bareness, rawness and roughness thrown in for good measure to show solidarity with the spotless proletariat so very fashionable and greatly admired at that time. Johnson commissioned Miës van der Rohe to design his Manhattan apartment, and returned to America starry-eyed and completely bowled over by the Modernist ethos he had absorbed, notably at Dessau, where the Bauhaus established by Walter Gropius (1883-1969) made a huge impression on him.

That was not all Johnson absorbed when in Germany: he became a devoted admirer of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and of National-Socialist views, subsequently becoming involved with the odious priest and anti-Semite, Charles Edward Coughlin (1891-1979), whose National Union Party (known as the ‘Grey Shirts’) was ideologically allied with German National Socialism, and for which Johnson designed its symbol, the flying wedge, a Swastika substitute. For Coughlin’s newspaper, Social Justice, Johnson wrote vile diatribes that make very unpleasant reading. Indeed, Johnson was ‘titillated by the æsthetics and sexuality’ of National Socialism, as one of his obituarists put it, and he subsequently observed the arrival of German troops in Poland with admiring approval.

However, before Johnson’s dalliance in disreputable politics, he, Hitchcock, and Barr organised the MoMA exhibition publicising work by ‘Le Corbusier’ (1887-1965), Gropius, Miës, J.J.P. Oud (1890-1963), and other Modernist architects in 1932, and it and the book of the same year by Johnson and Hitchcock coined the term ‘International Style’, which set in aspic the agenda for architecture for decades to come: indeed, after 1946 no other style was permissible, for the bullies and fascists who took over  architectural education thanks to the wholly malign influence of the Bauhäusler, left no choice. Any deviation was denounced in both architectural schools and among architectural ‘critics’. The damage done was universal. Johnson had supported both Miës and Gropius in attempts to get the Nazis to adopt the International Style (both men entered the architectural competition to design the new Reichsbank, and Miës signed a document supporting Hitler, published in the repulsive Nazi Party newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter, on 18 August 1934).

architectural education thanks to the wholly malign influence of the Bauhäusler, left no choice. Any deviation was denounced in both architectural schools and among architectural ‘critics’. The damage done was universal. Johnson had supported both Miës and Gropius in attempts to get the Nazis to adopt the International Style (both men entered the architectural competition to design the new Reichsbank, and Miës signed a document supporting Hitler, published in the repulsive Nazi Party newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter, on 18 August 1934).

Received Opinion has it that Gropius and Miës fled Germany as soon as Hitler came to power in 1933, but that is simply untrue. Both attempted to ingratiate themselves with the Nazis, and Miës did not leave Germany until 1938 after he had, through Johnson’s influence, been appointed to a teaching post in the USA (Johnson and others had already secured for Gropius a position at Harvard). Several other Bauhäusler were also embedded into the American art/architecture educational system, thereby, as Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (1903-71) sagely observed, infecting it with a bankrupt, negative, poisonous ideology, a phenomenon she aptly referred to as ‘Hitler’s Revenge,’ but one that after 1946 was eagerly embraced by powerful vested interests, such as the automobile industry, and passed into legislation, thus ensuring the wreckage of humane urban environments and the imposition of hellish dystopias. That Johnson was one of the most influential figures responsible for this disaster can hardly be disputed save by the most blinkered and myopic of observers.

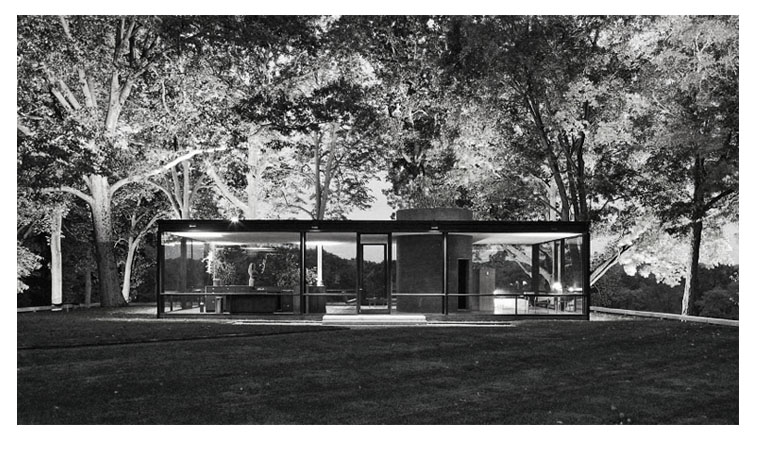

Johnson returned to Harvard to study architecture, but soon reversed his opinion of Gropius as an architect: perhaps the fact that Gropius (who could not draw) always needed collaborators who produced the goods, and that Johnson also required amanuenses, rang bells. As it happened, Johnson built for himself a house at Ash Street, Cambridge, MA, but did so with the help of his fellow-students. The design (his ‘thesis’ project) owed much to Mies (who had dropped the diæresis when he settled in the USA), and so managed to annoy Gropius, which was part of Johnson’s intention. Furthermore, Johnson was scornful of Gropius’s own house, finding it awkward, clumsy, and too proletarian for comfort: to him, Gropius was the ‘Warren G. Harding[1] of architecture,’ and Johnson claimed he would ‘rather sleep in the nave of Chartres Cathedral with the nearest john two blocks down the street’ than he would in a Gropius house ‘with back-to-back bathrooms’. Mies, on the other hand, was regarded almost as a deity for a time anyway, until Johnson, with Landes Gores (1919-91), designed and built the Glass House for himself at New Canaan, which pre-dated Mies’s Farnsworth House, and thereby annoyed the German, not least when the American became known as ‘Mies van der Johnson’.

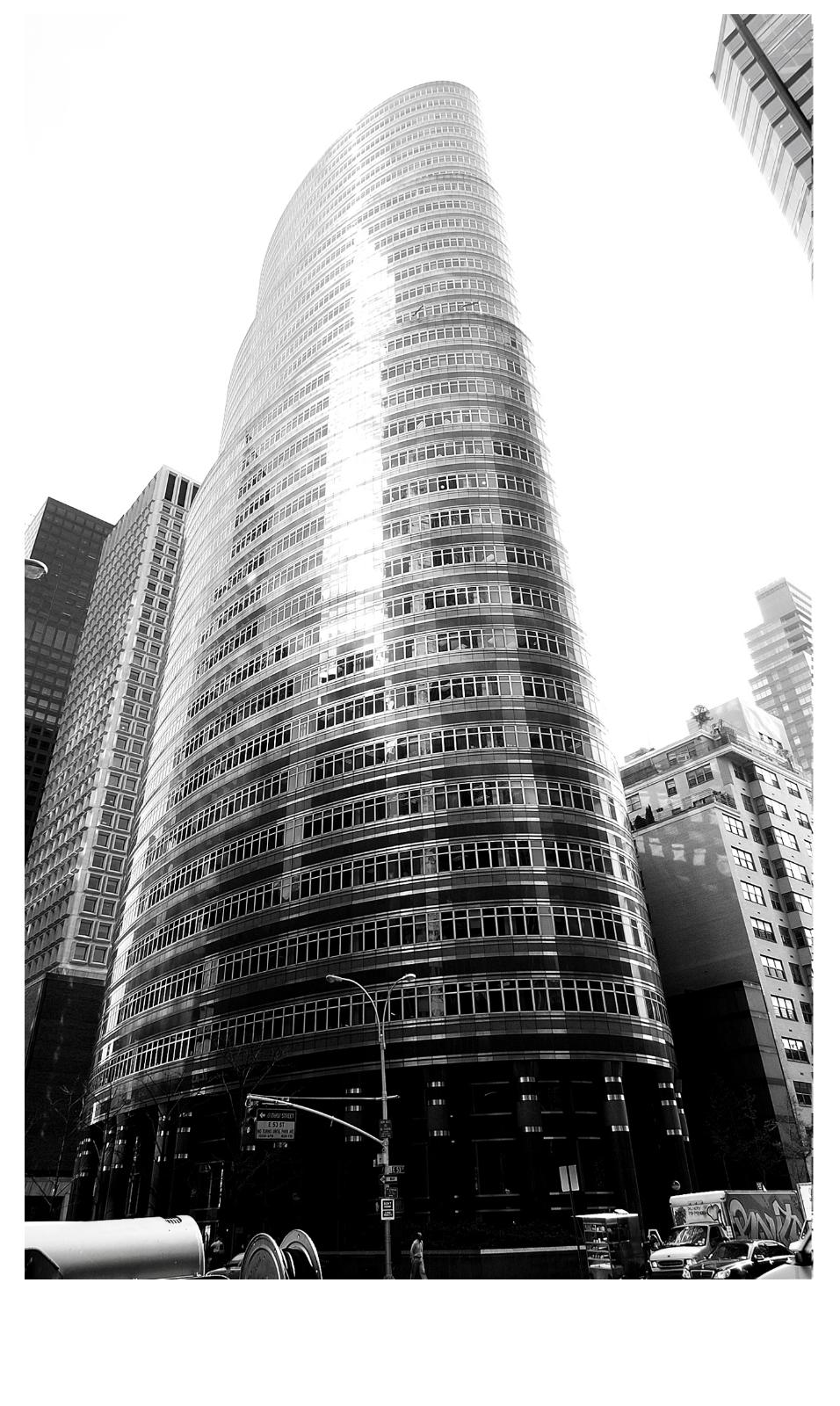

Then followed a whole series of private houses, and, together with his association with MoMA, put Johnson in a powerful position within the architectural mafia, consolidated with his 1953 Abby Rockefeller Sculpture Garden, New York. He was closely associated with Mies in the design of the Seagram Building, NYC (1954-8), thus furthering his status, but, now that the International Style had been universally accepted in America, he turned away from it, questioning Modernism’s spurious claims for ‘Functionalism’ and ‘Social Responsibility’, and attacking its fraudulent ‘morality’ (he had no qualms about exposing the shallow hypocrisy of architects, labelling them as ‘whores’, including himself). Rejecting all the claims that Modernism was a social, cultural, and economic movement, he firmly labelled it for what it was: a style, and a very limited, boring one at that. As an antidote, with his guest-house in the grounds at New Canaan (1952), Johnson created an interior of domical vaults springing from very slender uprights set against gold walls, deliberately High Camp, an exemplar of what Johnson called his ‘High-Queen’ or ‘Ballet Style’: an extravagant, sensual, pleasure-den, it made no secret of its purpose as a libidinous play-space, and sent shock-waves through the architectual world. The Impresario of the International Style had begin to twist its tail, sending up puritanical European Modernists and (especially) their servile British followers (his views on some of them were especially scathing, and with just cause, as they and their successors never wrote a word of worth).

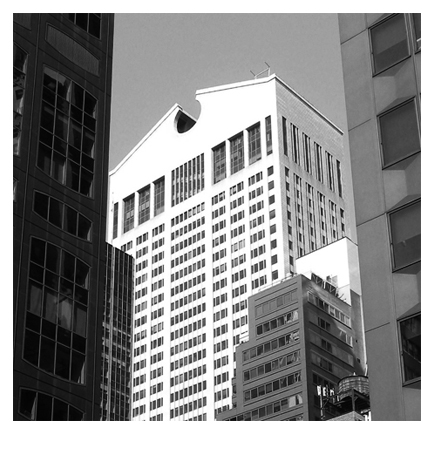

In partnership with John Henry Burgee (b.1933), Johnson designed the AT&T skyscraper, NYC (1978-84—later the Sony Building), a masonry-clad structure set on a stripped variation of a serliana-cum-triumphal-arch, and  capped by a paraphrase of an open-topped pediment. Denunciations became hysterical, which, of course, greatly amused Johnson, secure in his Olympian heights and confirmed in his views of the incurable dimness and conformity of British critics (Reyner Banham [1922-88] excelled even himself in his vituperations), and declared the work was conceived out of ‘sheer fatigue with the International Style’. Other works followed, sometimes embracing quirky historical details dangerously verging on Kitsch, but there is no doubt the Kitsch was intentional.

capped by a paraphrase of an open-topped pediment. Denunciations became hysterical, which, of course, greatly amused Johnson, secure in his Olympian heights and confirmed in his views of the incurable dimness and conformity of British critics (Reyner Banham [1922-88] excelled even himself in his vituperations), and declared the work was conceived out of ‘sheer fatigue with the International Style’. Other works followed, sometimes embracing quirky historical details dangerously verging on Kitsch, but there is no doubt the Kitsch was intentional.

Johnson had not yet run out of ideas to shock and surprise: he took considerable pleasure in chiding those with anaemic pretensions, and was irrepressible in his concerted activities to deflate pomposity, épater le Mouvement Moderne, and expose fools. He confounded critics by returning to MoMA to curate an exhibition on Deconstructivism (1988), thereby promoting the careers of Zaha Hadid (1950-2016), Rem Koolhaas (b.1944), Daniel Libeskind (b.1946), and others, and challenging perceptions of order and rationality, while undermining basic assumptions about building. His own tribute to Deconstructivism was his Da Monsta pavilion (without any right angles) at New Canaan, a send-up if ever there was one. Therefore, having shocked, Johnson went on to do something else, almost gleefully, leaving critics floundering in his wake: he promoted, practised, then subverted, the International Style; he did the same with Post-Modernism (PoMo); then repeated the feat with Deconstructivism, all of which adds up to quite a comment on the appalling shallowness of twentieth-century fashions in architecture and their apologists. He demonstrated a puckish disregard for what others thought (if thinking is the right word), and delighted in dreaming up the next way he could ridicule the Modern Movement, deny the divinities of Le Corbusier, Gropius, Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), et al., and annoy the humourless, outraged when he played at ‘sourcery’ with his ‘trivial historicism’ (the last a favourite word of abuse among Modernists, following the absurd posturings of Nikolaus Pevsner [1902-83]). He particularly poked fun at the English, who were so ‘good’ about ‘morals’ and ‘planning’ they had managed to ruin London with a cheap and nasty Modernism which disgraced any supposedly civilised country. His biting criticism of that old fraud, John Ruskin (1819-1900), in The Seven Crutches of Architecture, suggests something of his impish tendency to disrupt, dismiss, and radically change direction. When considering the convoluted apologies for, and dimwitted advocacies of, trendy architecture, as puffed in the RIBA Journal and The Grauniad, one can imagine Johnson’s wicked laughter echoing through the stratosphere.

Tellingly, Johnson told students that he was a ‘traditionalist’, believing in history (Gropius, in contrast, fresh from the edifying atmosphere in Berlin when books were burned, cleansed the architectural library of his new American empire by removing volumes savouring of pernicious historical architecture or anything connected with true scholarship, yet it never occurred to anyone that there might be parallels between such behaviour and the funeral-pyres of books in Germany), and that he did not hold with ‘perpetual revolution’ or in striving for ‘originality,’ because it was far better to be competent than original. He also stated he did not believe in principles either. In time he came to question the whole Modernist project from its very beginnings, something he was able to do from his privileged position as the ‘Midas of New York High Camp,’ as he was eloquently described. Yet Johnson was hugely responsible for the disaster that International Modernism inflicted on the world through the architectural schools; for the offensively crude PoMo that offends the sensibilities in far too many places; and for promoting the careers of dreary, unclubbable Deconstructivists. The last have induced a sense of dislocation, broken continuity, and disturbed relationships between exteriors and interiors: they have fractured connections; undermined harmony, unity, and perceived stability; and intentionally abused perceptive mechanisms in order to generate anxiety and discomfort. Thus the Modernist programme has been largely concerned with desensitisation, and, dear God!, it has succeeded.

Tellingly, Johnson told students that he was a ‘traditionalist’, believing in history (Gropius, in contrast, fresh from the edifying atmosphere in Berlin when books were burned, cleansed the architectural library of his new American empire by removing volumes savouring of pernicious historical architecture or anything connected with true scholarship, yet it never occurred to anyone that there might be parallels between such behaviour and the funeral-pyres of books in Germany), and that he did not hold with ‘perpetual revolution’ or in striving for ‘originality,’ because it was far better to be competent than original. He also stated he did not believe in principles either. In time he came to question the whole Modernist project from its very beginnings, something he was able to do from his privileged position as the ‘Midas of New York High Camp,’ as he was eloquently described. Yet Johnson was hugely responsible for the disaster that International Modernism inflicted on the world through the architectural schools; for the offensively crude PoMo that offends the sensibilities in far too many places; and for promoting the careers of dreary, unclubbable Deconstructivists. The last have induced a sense of dislocation, broken continuity, and disturbed relationships between exteriors and interiors: they have fractured connections; undermined harmony, unity, and perceived stability; and intentionally abused perceptive mechanisms in order to generate anxiety and discomfort. Thus the Modernist programme has been largely concerned with desensitisation, and, dear God!, it has succeeded.

Yet Johnson’s ridiculing of, and contempt for, unintelligent and hidebound scribblers, especially of the fatuous, sneering, reptilian English species inhabiting those dismal twilit worlds masquerading as architectural ‘journalism’ and inhabited by pseuds, was at least something in his favour, as was his undermining of the rigid cult of International Modernism. But against those, he did a great deal of damage, especially by promoting certain Deconstructivists whose influence has been anything but benign. Ultimately, Johnson may be seen as a more significant figure in the unedifying story of Modern architecture than any of the ertstwhile heroes, including Gropius, who was consistently over-rated, not least by himself, and especially by his starry-eyed admirer, Pevsner, and his latest hagiographer.[2]

Lamster’s book, a hefty tome of 509 pages, does not quite ‘get’ Johnson in all his infuriating guises, although it quotes Johnson saying that he had ‘never worked with anyone as bright and as quick and as decisive as Donald Trump’ (although Johnson was scathing about The Donald’s arriviste taste and complete lack of professional deference), and Trump (b.1946), in turn, described Johnson as ‘a great man’ whose ‘best work’ was ‘yet to come’, because a ‘lot of it’ was going to be Trump’s. Perhaps Trump was perceived through Warhol-tinted spectacles, as the essence of a gilded tycoon, but the combination of Johnson/Trump is perhaps indicative of something very curious.

Lamster’s use of colloquialisms, and even slang, is often distracting, his grammar is shaky at times, and the organisation of his text could have contributed to greater clarity. Nevertheless this is a revealing book about an important, if at times extremely unpleasant, character, but its author, taking Shakespeare’s injunction with depressing literalness, has absented himself entirely from felicity. It is not a pleasure to read, and nothing of wit, elegant prose, or agreeable style can be found therein to elevate the spirits or even mildly to amuse.

[1] Warren Gamaliel Harding (1865-1923), 29th and perhaps unjustly maligned President of the US.

[2] See The Jackdaw 146 (July/August 2019) 20-21.

James Stevens Curl is the author of the devastating critique, Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism (Oxford University Press 2018), and was honoured with an 2019 Arthur Ross Award for Excellence in History & Writing within the Classical Tradition by The Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (USA).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link