An Evening in France

by Theodore Dalrymple (August 2018)

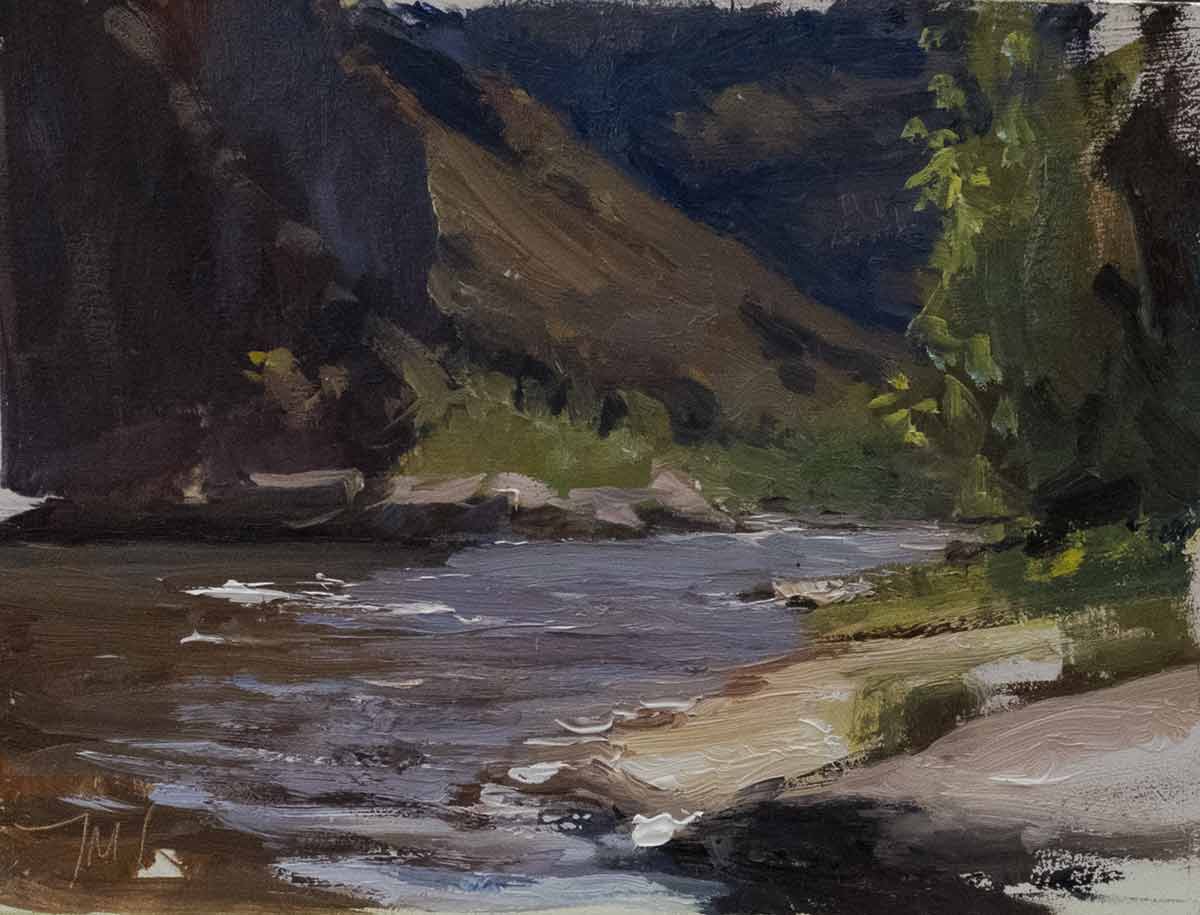

Les Gorges de l’Ardèche, Julian Merrow-Smith

One evening in France, quite a number of years ago, my wife and I enjoyed a convivial evening with her sister and brother-in-law and some friends. At the time, we were looking for a house in France to buy, and one of the friends said she knew of a whole abandoned hamlet in the Cevennes for sale, with about 250 acres of land: abandoned, that is, except by its owner, a former army officer, and a man in his eighties. We thought we might buy it and restore it, and then live happily all together ever after.

Having come to our senses, my wife and I nevertheless bought a house (for us alone) in the Ardèche, the department of France in which was the abandoned hamlet. This is a wild part of the country, in so far as anywhere in Europe can any longer be described as wild. It was always a hard place to live for the peasants, who left it en masse in the 1960s, easier alternatives for them having become available elsewhere, abandoning their villages wholesale. The soil is poor and stony, and the land, being on the side of hills and mountains, must be terraced in order to be workable at all. These terraces with dry stone walls had to be built by hand: pleasing to look at, provided you don’t have to build or maintain them yourself. The result of the labour of centuries is now in the process of crumbling away and will never be restored. Nor was the herculean labour ever rewarded by anything more than a bare subsistence. Even the climate, cold in winter and hot in summer, conspired to make life difficult.

After the events of May, 1968, however, the Ardèche was not only an area of emigration, but of immigration too. As many of the true peasants left, they were partially replaced by young idealists, that is to say sprigs of the urban bourgeoisie who, once the Parisian effervescence was over, came in search of the simple, authentic, healthy, rural, non-capitalist life. They formed communes that were intended to be radically egalitarian and non-materialistic. It helped, of course, that in many cases there were parents in the background with money. There was always something to fall back on.

Even today, half a century later, there is still a faint trace in the small town which is nearest to our house in the Ardèche of that movement back to the soil. A few geriatric hippies, still in their countercultural attire of oriental-ish cotton pyjamas and sandals, as much a uniform as that of the gendarmerie, wander the streets harmlessly. The men still try to grow ponytails, the women’s faces are crevassed by too much sun. And the area is still a magnet for younger counterculturals with dreadlocks and nose-rings, conspicuous rejection being to them what conspicuous consumption is to the nouveau riche. It is an illusion that never seems to die that wisdom and goodness resides in hairstyle.

Residing part-time in the area, I was naturally interested to read a book about three murders committed in the Ardèche more than forty years ago by the leaders of a back-to-the-land commune, the main culprit, Pierre Conty, having evaded capture ever since.

It is not even known if he is still alive, though it is known that he spent years in Sweden, North Africa and Switzerland. He was sentenced to death in absentia in 1980, just before France abolished the death penalty (his defence lawyer during his trial, Robert Badinter, was soon to be the minister of justice under whom the penalty was abolished), and under French law a man who evades capture for twenty years becomes a free man.

The book, Mon témoignage sur l’affaire Pierre Conty (My Testimony on the Case Pierre Conty: The Mad Killer of the Ardèche), Mareuil Éditions, was by a retired gendarme, Henri Klinz, who was patrolling the area with a colleague when they happened across Conty and two of his associates. Conty et al. had just held up a bank in the small town of Villefort, not very far from where I live. In the confrontation, the robbers shot at and then managed to disarm Klinz, and they shot his colleague in the abdomen several times, before making their escape. During this escape, they murdered a further two people, a father and son, shooting them cold-bloodedly in the head.

Klinz’s colleague, Dany Luczak by name, did not die straight away and Klinz managed to get him back to the local gendarmerie alive and still conscious. Eventually, he was helicoptered to Montpellier for surgery, but died twenty-six days later of septicaemia consequent upon his injuries and many operations. It was a terrible Calvary.

One does not usually expect to be moved by a law-enforcers memoirs, but Klinz’s book is moving because it is so patently sincere in its description of the events with which it is concerned. Klinz was only 25 at the time and Luczac 21. They had both only just started in their careers. He writes at the beginning of the book:

To recount as faithfully as possible not only the event but also the omissions in the subsequent investigation and the numerous mistakes in the media, and above all to give my own analysis: all this seems necessary to me today the lessen the burden that has weighed on my life for more than thirty-five years, a burden that has many times to expose myself to dangers, sometimes by provocation, hoping that a ‘replacement bullet’ would come to substitute for that which was destined for me that 24th August, 1977.

Elsewhere he says that if the same thing were to happen again, he would not plead for his life, as he did on that occasion, but would prefer to die. One senses that there is nothing exhibitionistic in this, that it is the literal truth. His is the most clearly expressed case of survivor guilt that I have read, and when he says that not a day has gone by since his colleague was shot without remembering what happened (though he was able to carry on his career, which was a successful one), I do not think he exaggerates. His book is a work of restoration, but the author knows that it cannot be complete. What has been lived cannot be unlived.

And what of Pierre Conty himself? He was the son of a factory worker in Grenoble, a communist by conviction. Conty, though, was more of an anarchist, perhaps because he was born with an outsized ego and discipline of any kind, political party or other, was unacceptable to him. He must have had some kind of charisma because he became the leader—at any rate a leader—of a commune in a nearly-abandoned hamlet called Rochebesse.

Most of the people attracted to the Rochebesse commune—and there were several hundred in all—were not like Conty (L), that is to say of proletarian stock, but rather of upper middle-class origin. Some of them, indeed, were sprigs of very prominent families, tired out by the constraints of their own wealth and privilege. They sought freedom from routine and sexual taboo. Of course, it all ended very badly, as such endeavours always do.

Violent by nature, Conty turned to robbery with violence once the commune could not support itself by its own efforts. No doubt he was not too reluctant to turn to it and thought of it not so much as crime as expropriation or restitution. He probably enjoyed the excitement of it too. It was more interesting than herding goats.

Klinz’s first contact with the commune was not very encouraging. Patrolling his beat, the first house he saw in Rochebesse was festooned with a large slogan: Mort aux flics, Death to the Cops. Even so, he did not imagine that these words would turn out to be more than metaphorical. Much of the radicalism of the epoch was largely theatrical, and in fact most of the members of the commune later settled down into normal, or even important, jobs. A few did stay behind, but lived in couples rather than in communes.

In the course of writing this book, Klinz did a lot of research. He interviewed some of the participants in Conty’s commune and even spoke to a couple of his lovers. There is a photo of one of them in the book, sitting in what looks like a well-furnished and comfortable sitting room or study. She is much beringed and very well-preserved. She is well-dressed and looks out at the camera with clear force of character and, I should guess, a fierce intelligence.

the famous photo that adorns a thousand tea-towels, watch-faces, boxes of fudge, covers of exercise books, and other products of radical kitsch or kitsch radicalism. Che started as a murderer and ended as Mickey Mouse.

But these two pictures on the dresser suggested to me that Conty’s former lover, Hélène Terrisse by name, was still sentimentally attached to the ‘ideals’ of her youth and saw no intrinsic connection between Conty’s ideology and his acts. Indeed, it is possible that she made excuses for those acts. Even after it was clear that he had killed, and killed brutally, he received support from the commune milieu. The group loyalty of extreme egotists often means more to them than civilised behaviour.

Conty’s two accomplices in the murders turned themselves in, both of them denizens in their childhood and youth of Paris’ most chic area. One of them served eighteen years in prison and the other, who claimed only to be the chauffeur of the killers five, though Klinz thinks he was much more important than he made out, and may even have been Conty’s intellectual inspiration.

Klinz describes in comic detail the inefficiency and incompetence of the gendarmerie. When the chief of the gendarmerie comes to the Ardèche from his Parisian fastness, he is more concerned about the puncture his official car has sustained than with finding Conty. Furthermore, no one can be found willing to repair it because, to raise the money to pay for it, the bill for payment must be sent to headquarters to obtain authorisation for payment etc., and no repairer wants to wait that long for his money.

_____________________________

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast