An Irish Lullaby

by Larry McCloskey (April 2023)

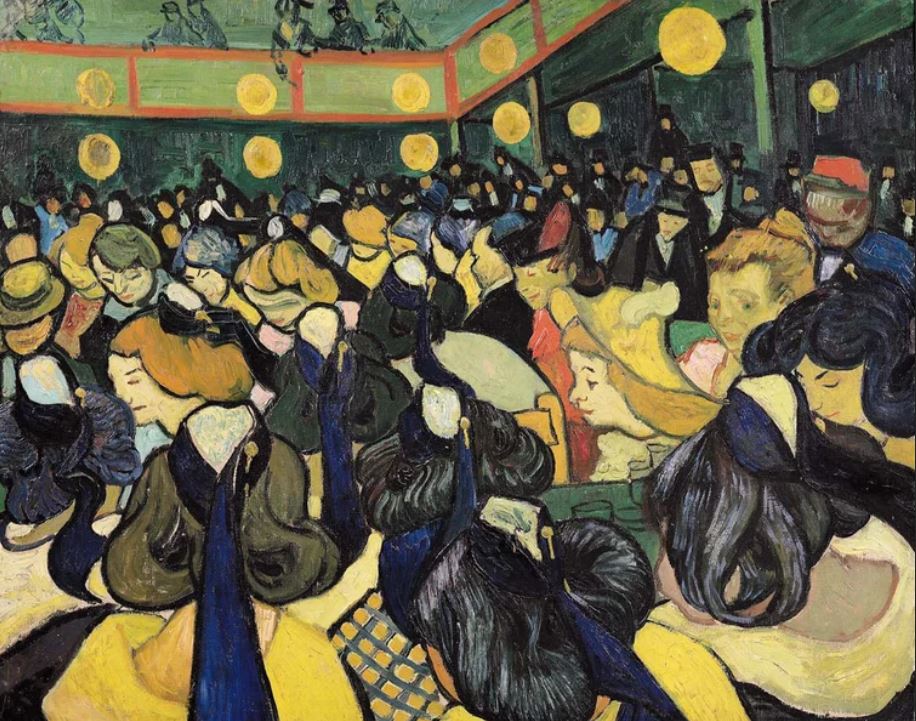

Dance Hall at Arles, Vincent van Gogh, 1888

My warped version of mindfulness is deeply embedded in nostalgia; that is, a desire to slow down and hold on to that which will later only be accessed and appreciated by memory. Without the anchor of what, and more important, who matters, what could staying in the moment possibility mean? Same for the future—our anxiety over it, and what we desire from it is only informed by what we have experienced, who we have valued and moments we would like to recreate in the future.

Staying in the moment without the bedrock of the past is a blank slate—and yes, I understand that blank is supposed to be enough, but it isn’t. (My best Buddhist friend has never been able to explain to my satisfaction, or his for that matter, how to reconcile the blank concept of non-attachment with the singularity of love). The fulfillment of staying in the moment, as commonly articulated but little understood, is actually closer to the experience of dementia than nirvana. I am reconciled to not being invited to headline the next conference on mindfulness.

I am particularly nostalgic for my long dead parents on this grey, snowy week leading up to St. Patrick’s Day. In my northern location, grey feelings this time of year are exacerbated by the promise of spring without any hint of its fulfillment.

We grew up without much sense of identity. Our parents and their generation’s notion of identity had less to do with particulars of birth than what you did with what you were given, however modest nature’s contribution. We knew we were Catholic, and vaguely knew we were Irish, in that cornball, shamrock wearing, leprechaun version of St. Paddy’s Day common to the extensive post potato-famine Irish diaspora.

Partly, we thought we were boring and lacked identity because we were not part of the O’Neill clan on my mother’s side who vacated Canada for sunny California just after the Second World War. Only our parents chose to remain, and we grew up thinking they had forsaken celebrity, Hollywood glitter and sunny skies for cold, boredom and a nondescript version of what life could be.

My great uncle Jack O’Neill moved to California from a tiny farming community outside Ottawa, Canada in the 1930’s and made his considerable fortune. He owned theatres, extensive real-estate, TV and radio stations, was featured in Life magazine, and hung with the likes of Walt Disney and Ed Sullivan. The latter once famously extended a personal greeting to his friend Jack on the west coast during his popular Sunday evening variety show. After he died, President Kennedy was the guest speaker at a placard unveiling and tribute to Jack O’Neill for his leadership in creating an irrigation system that made the Californian agricultural miracle possible.

With decidedly less glamour, we later learned that our McCloskey Irish identity had a modicum of distinction. Both my parents were Irish decedents of potato famine Irish consigned to Canada, rather than the more desirable locations of United States or Australia, because of poverty. We think some of our early famine relatives worked on the famed Rideau Canal—where a thousand Irish workers died from Canada’s only outbreak of malaria. McCloskey relatives then settled on hilly land with a dozen other Irish families in what is now the Gatineau Park, about 10 miles north of Ottawa. They actually tried to farm this Canadian Shield melange of rock, trees, and notably, poor soil, until presumably someone spotted the fertile river valley below and the entire clan vacated barely arable land for greener pastures around 1930. Interestingly, for early settlers born in Ireland, their first language was Celtic or Irish, and learning English and possibly French, only happened after landing in Canada. At the time, shop keepers in Ottawa’s Byward Market were openly prejudiced against the lowly rift-raft Irish, prominently displaying NINA signs: No Irish Need Apply. The Irish were not privileged. Today, visitors to Gatineau Park only know McCloskey Road as one of many hiking and cross-country ski trails.

I’ve often wondered about the people who inhabited the farm hovels along McCloskey Road 175 years ago. Did they get along, did they like each other, were they literate, did they have a vaguely similar inbred look, did they play music, practice that high Irish art of slagging with a perfectly timed pun to pass long winter nights? Were they as narrow and clannish as assumed, or did they pine for release from expectation and entry into the big, bad world? With the little history we know, and with the physical difficultly of navigating the rudimentary path down from the Gatineau hills towards the first remnant of civilization, it is likely many of the inhabitants never visited Ottawa in their lifetime, today a fifteen-minute drive.

There is a photo, circa 1970, of my mom, dad and youngest brother, standing under a newly installed McCloskey Road sign, while holding the old discarded hand-painted wooden version.

It was out of character for my dad to take a memento from a history we didn’t then know existed, but that is what he did, and it remains one of the very few tangible relics of our family’s past.

But what most brought our Irishness into focus was a letter written by my mother to her sisters—they newly and permanently relocated to California—as she prepares to go on a date. We only found this letter after my mom’s death in 2000. As was the convention of the day, letters could be written over a period of several days in order to capture all the news from afar. Mom, known as Enie, informs her sisters that she has met a new fella (the one), an Irish guy named Leonard Patrick McCloskey, whose birthday just happens to be on the day she is writing this letter, St. Patrick’s Day, March 17th, 1947. She says she will finish the letter tomorrow because to celebrate both Patrick’s and Leonard’s birthdays, they are heading to the Standish hotel (notable for big band performances) for an Irish dance. The California exodus, happening over a period of some years as people gaged the progress of relatives, was effectively cancelled for mom with the advent of her new fella. The letter, informative, direct, sincere and, without knowing but anticipating a life together, is poignant as hell. It is true I have a penchant for allowing nostalgia to bleed into romanticism, and feeling the presence of this 75 year old letter in the present, is my only pathetic excuse. The problem is not failure to stay in the moment; the problem is understanding the immediacy of a past that is not and will never be past. An important, if unoriginal, thought.

My parents and their contemporaries comprised the greatest generation (an indisputable, if blatant, stereotype that I am comfortable making). Mom and Dad grew up during the depression, graduated into the Second World War which they dispensed with in magnificent fashion, married and had seven kids in rapid succession, and were not exceptional for all that. They knew deprivation, hardship, community, church and family. They lived with sacrifice and purpose, and both had an early, hard exit from this mortal coil. Dad first, age 59, from smoking and drinking; that is, self-medicating for excruciating pain after breaking his back during the Second World War. His spinal injuries were numerous, he was in medical text books of the day after being operated on by the renowned neurosurgeon, Dr. Wilder Penfield at the Montreal Neurological Institute, and he returned to active duty as a flag man within the year. His return within that timeframe was not considered possible, if not for the fact he did just that. There was not a day in life he was not in pain; there was not a day in my life he ever complained about pain.

My mom and all her Irish women friends lived long after their Irish husbands died. I was struck by this fact walking into her living room one evening with ‘the gals’ over for six hand euchre. These conventional, unconventional stereotype-defying women—all Irish, likely related, and with the average number of kids being six—were lively, energetic and grateful for the euchre moment that they would later feel nostalgic for, and I still do. I knew their histories, husbands, and present challenges—especially those whose adult kids continued to give them grief—and yet, they were what can only be described as happy (the secret being never aspiring to and being surprised by its happening). My mom, who later developed Parkinson’s Disease, the others with equally sad endings, would not have relinquished a laugh, their present happiness or later moments of nostalgia for knowing the gruesome future to come, which makes them all the more inexplicable, remarkable, and mysterious. Yes, these women I knew so well I didn’t know at all, and the unfathomable mystery of their lives and death remains a bittersweet nostalgic preoccupation. And yes, by now I might as well admit that preoccupation is an affliction that I refuse to surrender.

The men’s endings were earlier and harsher. Turns out that the smoke and drink combo really did have consequences, but by God, they had a good time, their Irish version of mindfulness unrecognizable today. While the celebration of St. Paddy’s day may have been mostly schlock, there was a version of being Ottawa Valley Irish that was as authentic as a Dublin Pub (of which there are 1000).

Each summer we and other large Irish Catholic families gathered at the Kennedy farm for the annual picnic. The day started early with an afternoon picnic, but sharing a meal was not the main event. While adults got reacquainted, the kids who outnumbered the parents about four to one, roamed the fields and forest for adventure. Then games—horseshoes a favourite—a hayride, and of course, music. Accomplished fiddlers, who no one suspected could play until they did, created a festive and distinctly Irish mood. Fiddling events such this that once flooded the Valley with music, are rarely heard today. Partly tastes have changed, partly people don’t gather as they once did, and partly, the fact that the fiddlers are all dead, has to be considered. Food eaten, darkness descending, adults indulged in a wee nip of the drink, with tolerance for us adventure seeking little shiites as expansive as ever existed.

No one thought about danger as carloads of unseat-belted kids set out for the 45 minute drive home. The drive home was usually a forgetful dreary snooze, with me laying across the back shelf of the backseat, our sardine-like routine for squeezing in the requisite number of bodies. But the last journey of the last Kennedy picnic became a highlight of our limited family mythology. Somehow in our old packed Ford, which included my parents and their six kids (the seventh, a late, delightful surprise to come), we managed to sneak a large mangy farm dog. The dog, my first true love, instantly became part of our large, chaotic, unwieldy family. We didn’t know it then, but the vagueness of our family’s identity was coming into focus. There were many other family features in the mix, and not all good, but we were no longer, as previously assumed, completely boring. We weren’t exactly exciting, as we imagined our Californian cousins to be, but at least we had a history, with a deeply flawed, but endearing group of people. A community, home. And given the now into which we find ourselves, a flawed past, untethered from politics and revisionist history, is worthy of nostalgia.

Our identity within that community was perhaps best defined as get over yourself. Families with seven or nine kids didn’t dispense much attention on any one of them. It was more than a numbers game. The cultural norm in our un-emotive Irish Catholic way did not easily tolerate placing oneself on a pedestal. Good looks, talent, frivolous boasts, claims of glory yet to come, were regarded with deep suspicion. Distinguishing oneself came later, if at all, based on what you accomplished, and even that possibility was as a result of what others said about you. After being buried and indistinguishable among many siblings, we hungered to achieve something in life outside family and community. Our notion of a home that we could return to was necessitated by leaving it in the first place. As the years passed, we tended to disparage our own tribe more than any other—a tendency accelerated by the Catholic priest sex scandals—in manner antithetical to identify politics today. I don’t remember ever feeling superior to anyone though I do remember feeling inferior. And yet a far different interpretation of our history, from among those who never lived it, has come to be.

The currency of nostalgia is low; the tide of reimagined history is high. The flawed past, if we go there, is to be remembered through the prism of revisionist history, and that history will always be inferior to what should have been. Flaws fondly remembered from the community that spanked and hugged us into existence has been repackaged as blatant prejudice and stupidity. Wisdom is not a natural progression from old to young as a consequence of a life well-lived, but rather is achieved through borrowed thinking and fashionable causes. Leadership too is adopting the most appropriate cause and telling others to do the same. Considering alternative views or information that challenges orthodoxy unpinning the proper cause is to spread disinformation.

My Irish Catholic tribe, flawed and narrow, was not exemplary. Nor was it, in negotiating the harsh realities of life and death, very serious. Though woke others see find oppression, we who lived it have difficultly finding these deep insights. Simple as we were, we were irreverent without being political, more interested in humour than hubris. For example, one astonishingly hot, humid Saturday in the mid-sixties Joe Brennan comes over for a large rye with a single ice cube, as was his habit. He and my father sit at the kitchen table and talk; that is, Joe Brennan tells tales, my dad nods his head, and we, whose presence is conditionally tolerated, listen. After an hour or so he turns to me, and says ‘son’—not knowing my name or positioning in the brood—and asks ‘would you take a glass of water out to my car for my wife, Loretta? She’ll be getting awful thirty out there by now.’ My mom’s shrill believing exclamation followed by her disbelieving laugher still a thrill in my nostalgic mind’s ear.

Before modernity liberated us to a world without limits, our limitations were everywhere. Monseigneur Bambrick, using words no alter boy should hear to describe feelings about that dam Protestant marrying a Catholic in his church in one hour, comes to mind. Still, there was a difference with a distinction. I always assumed the roots of stable change to be marrying the need for change to the equally strong need to conserve. That is, the generational bargain always was— and I use this past tense with regret and nostalgia— achieving an agreed upon balance between an incremental letting go of social mores no longer relevant, with the same determination to preserve values that matter. That is, until the purveyors of the cultural wars declared a moratorium, followed by a war, on balance.

We cannot value or feel nostalgic for a past that needs correction in it’s entirety. This is true even before considering the arrogance of thinking that history is a linear movement towards ever more progressive, superior thinking. And I would argue that much of one’s identity that uplifts and sustains today comes from regard for a past that continues to be relevant or at least creates curiosity. Very oddly, I invoke a famous Malcolm X quote for my argument about the need for continuity of values: a man who stands for nothing will fall for anything. Without the vessel or context of what was, we will be blown about, grasp at anything to give us meaning in the present which is to consign ourselves to life without a meaningful future. Or to put a finer point on it, a future that evolves without the context of the past will devolve into chaos and ruin.

A vacuum will not do. We need to believe and our narrow tribe can help to inform our beliefs, but should not determine all our values. Limited as our world may have been, we were determined to break from it, to create something for our individual selves before circling back for participation into its flawed fold. And for the record, our silly worn mythology, equal parts embellishment and revisionist humour, was never intended to be exclusive, was always a place where sane people would channel Groucho Marx and not want to belong. Or take seriously.

My parents, the euchre gals, and the fiddlers—all dead—would have been surprised to learn that their mostly forgotten lives remain in need of correction. Why stop there? There are millions of people with millions of small narrow stories such as mine who are guilty of nostalgia but remain innocent of oppression.

We are losing the cultural wars. History is being rewritten and statues are coming down, but it is more than that. The signs are everywhere, the ubiquitous new normal. The silver lining for me—stretch as it is— is that in the wake of woke I can revise my nostalgic affliction as subversive resistance. At least, that’s my story while I remain free to write one.

Table of Contents

Larry McCloskey has had eight books published, six young adult as well as two recent non-fiction books. Lament for Spilt Porter and Inarticulate Speech of the Heart (2018 & 2020 respectively) won national Word Guild awards. Inarticulate won best Canadian manuscript in 2020 and recently won a second Word Guild Award as a published work. He recently retired as Director of the Paul Menton Centre for Students with Disabilities, Carleton University. Since then, he has written a satirical novel entitled The University of Lost Causes, and has qualified as a Social Work Psychotherapist. He lives in Canada with his three daughters, two dogs, and last, but far from least, one wife.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast