Apprentices of the Artist of All Artists

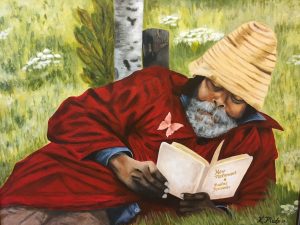

Resting in God’s Word by Karen Plude

by Jeff Plude (March 2022)

Evangelical Christians in America seem to have an uneasiness about the fine arts. This apparent aversion among the faithful baffles and frustrates me, since I’m both a believer in Christ and an admirer of art.

First, the Bible is full of descriptions and even demonstrations of art; the King James version itself is the apex of eloquence and literature in the English-speaking world, which even some atheists concede. And art not only affects the human spirit or soul, which is the primary concern of Christianity, but often embodies the very essence of the faith. And there is God himself, the ultimate and supreme Creator who made the heavens and the earth and “the fulness thereof,” and when he was done, he looked at it all and declared that “it was good.” And it still is! It’s a creation so sublime in its natural beauty and ingenious in its structure that even godless naturalists and primitives have celebrated it.

So if man is made in God’s image, as Christians certainly should believe, then why shouldn’t his children be artists too, and why shouldn’t that art be good? Yet many believers we have come to know in the two evangelical churches we’ve attended over the past five years seem to care very little about art, and even seem suspicious of it. Now being discerning about art is one thing but being suspicious of it is something else.

A case in point is when my wife has shown iPhone photos of some of her paintings to some of the fellow believers we’ve become acquainted with, they’re generally oblivious. All this seems particularly strange to us since my wife is a figurative painter, that is, her paintings are based on objects that exist in the real world—the world that was created by God and that God declared was good—though they’re impressionistic and by no means strictly realistic. But God isn’t a strict realist either. As one commentator has noted, God instructed Moses to decorate the fringe of the priests’ robes with textile pomegranates colored blue. Real pomegranates, of course, aren’t blue.

My wife’s latest painting (which hangs over our fireplace) even has an overt Christian theme, only the second one of three dozen paintings: a black man with a bushy grayish-white beard reclining on one elbow on the grass and wearing a distinctive straw-colored hat and a red coat with intricate folds, blithely absorbed in reading a copy of the New Testament with Psalms and Proverbs. When my wife and I were chatting with our new pastor, who’s in his late thirties and who’s a cartoonist himself, and showed him the painting, he said almost nothing.

He seemed oblivious that painting is more than just a hobby for my wife, though she has a full-time job as well. One of her paintings, for instance, was among fifty pieces chosen out of three hundred and fifty artworks to be part of a juried show at the Ridgefield Arts Council Gallery in Connecticut; she’s also had two well-attended solo exhibitions in Manhattan and Westchester County; for a couple of years she attended weekly life drawing sessions at the Art Students League of New York.

In contrast, “Resting in God’s Word” got enthusiastic responses when it was shown to our old friends and some acquaintances at a good-sized backyard barbecue. Interestingly, almost all of them, if not all, aren’t believers. And only one of them has any artistic background. The rest are working-class people who have no formal experience in art. And what’s more, strangers we’ve met on the road have been effusive about this painting and some of my wife’s other works. They had no dog or dogma in this hunt.

I don’t think the Christians we’ve encountered consider art sinful, at least in a general sense. Of course their reactions may be more personally motivated. But I think that many may wonder why any Christian would waste time on art at all. That it’s not preaching the gospel, or a ministry of some sort. Unless of course it’s contemporary Christian music, or better yet Christian movies, which they are prone to praise even when they’re not well done.

Now I don’t enjoy all forms of the fine arts. For instance, I have no use for opera. And so-called modern art, with its nihilism and charlatanism à la Mark Rothko, I don’t consider art at all. And there are the wolfpacks of so-called artists who are no more than political hacks with palettes instead of speeches.

But I think for Christians to dismiss good art out of hand—true and beautiful art, whether of a Christian subject or not—deprives them of a God-given blessing. Why should unbelievers be the only ones to enjoy and be energized and even enlightened by this divine gift? There’s no inherent sin in art. When the second of the Ten Commandments decrees “Thou shalt make no graven image, or any likeness of any thing … that is in the earth,” it’s clear from the preceding and the subsequent verses why the practice is forbidden: “Thou shalt have no other gods before me” and “Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them.” It isn’t creating art that’s a sin; it’s making an idol of it that’s a sin, just as the Israelites were doing at that very moment with the golden calf.

This Christian suspicion of art has powerful precedence as long ago as Augustine, who denounced the theater for inciting lust and for its pagan origins in Greece (though he was a rhetorician himself, a sort of quasi-artist, and used that skill to write his many famous books). He also wrote of the censorship of art as described in Plato’s Republic. But I don’t believe this was a blanket condemnation of all art. Surely Augustine would have admired Michelangelo’s The Pietà and the Sistine Chapel. And what about the Christian influence and aspects in Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies alike?

But as Leo Tolstoy points out in What Is Art?, some of the statuary and paintings in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches became icons that people prayed to—exactly what the second commandment expressly forbids. Tolstoy also shows a great deal of skepticism about art, and attempts to trace its development and then degeneration starting in the Renaissance up through the nineteenth century. I think the problem with What Is Art? is that Tolstoy overcorrects, and at times anoints works of art as superior that I doubt are. Maybe his treatise says as much about his own regrets for his motives for creating the literary juggernauts War and Peace and Anna Karenina than it does about what constitutes true and good art.

I think Francis Schaeffer, a theologian, philosopher, and evangelical pastor who was born a couple of years after Tolstoy died in 1910, was much closer to the truth. A half century ago, in 1973, Schaeffer wrote a long essay called “Art and the Bible.” He opens with a series of rhetorical challenges:

What is the place of art in a Christian’s life? Is art—especially the fine arts of painting and music—simply a way to bring in worldliness through the back door? We know that poetry may be used to praise God in, say, the psalms and maybe even in modern hymns. But what about sculpture or drama? Do these have any place in the Christian life? Shouldn’t a Christian focus his gaze steadily on “religious things” alone and forget about art and culture?

This is exactly what my wife and I were wondering when we became believers over a decade ago. Schaeffer (the one who mentioned the blue pomegranates on the priests’ robes) is the anti-Augustine in this respect.

Schaeffer explains how a Christian should evaluate art. First there’s the technical quality. Art needs to be well made to be good art. In a related criterion, there’s also whether the art “uses the normal definitions of words in normal syntax.” In other words, are the language or visual elements based on God’s world? If not, there’s no real communication with the viewer because there’s no common language. Abstract painting fails this test. Then there’s the validity of the artwork, or what nowadays might be called authenticity. Is the artist just trying to please the critics or the public, or is this what he or she truly wants to say? Next is the worldview: does the piece portray the beauty of God’s creation or biblical virtues? Interestingly, this doesn’t mean the art needs to be explicitly Christian. I think not only of Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son but of his self-portraits, not only of Bruegel the Elder’s The Tower of Babel but of The Peasant Wedding. I think of Millet’s peasants working in the field because “from the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread.” I also think of Van Gogh, who initially set out to become a Christian minister, and his bursting portraits and landscapes, his striking series of still lifes like A Pair of Shoes and The Bedroom. Finally, there’s whether the form fits the content. Schaeffer says even Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (which portrays prostitutes in a brothel) and T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” perfectly fit the form of their fragmentary works to man’s dislocation in the modern world.

Schaeffer describes how the Old Testament makes it abundantly clear how much God valued art. His explicit, elaborate blueprints that he communicated through Moses for how the Israelites were to build and decorate the tabernacle, the ark, and the clerical garments. God did the same thing with David regarding the Temple (though it was actually built by Solomon).

What Schaeffer doesn’t mention are the masterful stories in the Bible. I believe that Jesus was the greatest storyteller of all time; for instance, The Prodigal Son is the perfect story perfectly told. The Old Testament is as dramatic as a classic old-style novel. Think of how God spins the tale of Joseph—his older brothers betraying him (the second youngest of the twelve patriarchs) because he was their father’s favorite, being enslaved by the Egyptians, becoming a favorite of the pharaoh’s captain and his wife, being cast into prison after rejecting the wife’s advances and being falsely accused of trying to seduce her, his interpreting dreams under the guidance of God, his being let out of prison and rising to be pharaoh’s right hand man and in charge of Egypt, his reuniting with his brothers and dying elderly father and saving them and all the Israelites from starvation and destruction. Joseph and His Coat of Many Colors was the first book I remember being captivated by. I was in grade school and had ordered it from Weekly Reader, not having any idea it was from the Bible even though I was a Catholic boy.

Schaeffer also talks about architecture, which is definitely a verboten subject for evangelicals. After all it was the Catholic Church that built the great cathedrals, like St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and Notre-Dame de Paris. Both are magnificent when seen in person, but that they went too far, in my view, is obvious. They are more like palaces than churches.

Yet Schaeffer points out that young people often expressed to him that evangelical churches were generally less than beautiful. And it’s my impression that, fifty years later, it’s still true. The church my wife and I currently attend looks like a community center. Its exterior is ivory colored and has a gabled roof. The inside is essentially a gymnasium. The floor has the markings of a basketball court, and there are backboards with rims folded up toward the ceiling. There’s a stage on the far side that doubles as a bandstand and pulpit.

So if God enjoyed beauty, why is it sinful to have a beautiful-looking church without going overboard as the Catholic Church did? For my money the best-looking churches are the simple elegance of the old New England–style buildings with the shiny wood-and-white interiors and pews.

John Keats, after lamenting that art outlasts an individual life, ends his “Ode on a Grecian Urn” with: “Truth is beauty, and beauty truth,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

Truth is indeed beauty and vice versa, but that’s not quite all you need to know. But, as Pilate asked Jesus, “What is truth?” Jesus said nothing, but he told his apostles (and us) what we need to know: “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the father, but by me.” And isn’t there divine beauty as well as truth in Christ’s Passion?

God is the Artist of all artists. And his children who have followed in his creative footsteps—like the Israelite artisans in Exodus whom he filled with “wisdom, understanding, and in knowledge, and in all manner of workmanship, to devise cunning works”—are all his apprentices.

__________________________________

Jeff Plude is a Contributing Editor to New English Review. He was a daily newspaper reporter and editor for the better part of a decade before he became a freelance writer. He has an MA in English literature from the University of Virginia. An evangelical Christian, he also writes fiction and is a freelance editor of novels and nonfiction books.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast