Apres-Snowshoe

Soon there will probably be a foot or more of snow on the ground. It’s always a bit depressing to think about. There’s a solitude with snow, and we can no longer do a lot of what we consider the good things. You can’t swim in the snow, for instance, though I once took a dip with the Lake George Polar Club on New Year’s Day.

Winter sports, of course, make snow more palatable, even enjoyable.

Though I grew up only about a hundred miles from Lake Placid, which has hosted the Winter Olympics twice, and only about half that distance from Stowe, Vermont, I’ve never downhill skied. But I wanted to when I was a kid. I remember first watching the winter games in 1972, and I was thrilled by the men’s downhill. The skiers careened down the mountainside nearly out of control, wrenched out of their crouch as their skis suddenly became airborne, some spectacularly wiping out and others miraculously holding on and crossing the finish line. When I was in eighth or ninth grade a well-off aunt of mine was going to pay for me to take Alpine skiing lessons with her son at the local mini-mountain. But I had started wrestling and that was in the winter and I was very dedicated to it so I declined.

Then two decades later I took up cross-country skiing. Nordic skiing had became popular and my wife and I each bought a pair of skis, poles, and boots. And that’s some of the most grueling exercise I’ve ever done! Which is saying something, because I was used to two-hour wrestling practices of sparring, drilling, and conditioning. In my early thirties I was still jumping rope and lifting weights.

Also in the back of my mind was the Hemingway short story, called simply “Cross-Country Snow.” Hemingway brilliantly describes telemark skiing, where the skier kneels one leg and turns his skis while descending a real mountain, not some groomed trail like in the modern version of downhill skiing. Nick Adams and his buddy George enjoy a blissful day skiing and then stop at this rustic inn and prop their skis against the side of the building. They go inside and order some wine and strudel and lament how their time together is almost over, George has to go back to college and is leaving that night from Montreux.

I remember one Valentine’s Day weekend when my wife and I went cross-country skiing. It was idyllic! (a word that Hemingway turns on its head in another short story that features skiing, “An Alpine Idyll”). There was a fresh dumping of snow, about a foot and a half, and we drove east of Albany almost into Massachusetts and there was a small wood building where you paid and people were sitting on benches and at wood tables in their skiing gear sipping coffee and hot chocolate.

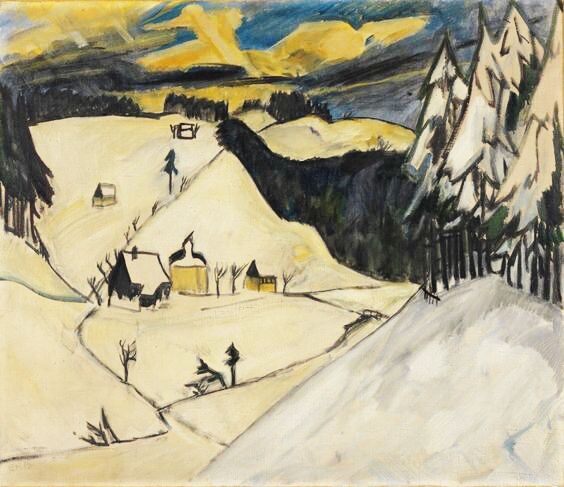

Outside in the woods we glided along on our skis through the thick, snow-covered, drooping pines, threading through the semigroomed trails. It was very quiet, except for my breath and the swishing of the skis. I tried to remember, as a book I bought said, to keep a “soft knee” when you cross-country ski, in other words, keep a low center of gravity (the same is true in wrestling). Which generally people don’t seem to do when I see them cross-country skiing—they look more like they’re walking. I sailed down one fairly long incline in a crouch, similar to the downhill Olympians I had admired as a boy. But when you go uphill you have to point your skis outward at an angle, like an inverted triangle, and step alternately with each ski. People tend to think there’s nothing to cross-country skiing compared to downhill, but I don’t think that’s quite true, if you do it right.

But on another day, a couple of years later, after cross-country skiing in the southern Adirondacks I was sore for a few days—and I was only in my mid-thirties! That was the last time my wife and I cross-country skied.

Around the same time I became intrigued with snowshoeing. One of the printers in the back shop of the newspaper I worked for used to snowshoe every weekend and raved about it to me when I went back to proof my pages. It seemed like a more leisurely form of cross-country skiing, with all the benefits and none of the drawbacks, like aching and tired muscles and bones. Of course the first North American snowshoers were the Native Americans. It was in my blood, perhaps, being descended on both paternal and maternal sides from French Canadians in Québec, whose fur trappers and traders and the like learned about snowshoeing from the Algonquins and the Hurons.

Even missionary priests, in their quest to convert the Indians, strapped on snowshoes. Francis Parkman, in The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century, recounts how Paul Le Jeune, who was about to join the Indians as they set out for their winter hunt, practiced with the long, tennis-racket snowshoes: the priest endured “all the mishaps which attend beginners—the trippings, the falls, and headlong dives into the soft drifts, amid the laughter of the Indians.”

That wasn’t the half of it—it was to be a trial by fire for Le Jeune, though the flames were frigid. He and the band of Hurons hiked in the mountains through knee-deep snow with all their belongings on their backs, “each man, woman, and child bending under a heavy load …. The Jesuit was loaded like the rest.” Le Jeune must’ve been pretty hardy, since he was forty-two at the time. When they reached their destination after a couple of weeks, on November, 12, 1633, the men of the tribe then took off their snowshoes and used them as shovels to dig wigwams out of the snow, whose walls were three or four feet high. The women cut the poles out of saplings and covered them with birch bark, hung a bearskin at the doorway, and lined the walls and floor with boughs of pine.

So I decided to write a feature story about snowshoeing. I found an Adirondacker who gave workshops about how he made snowshoes and then led the group up Mount Jo—on snowshoes. He made them from wood, and they were beautiful but expensive. Most snowshoes, even back in the mid-nineties, had aluminum frames. These days even a basic pair of those will set you back upwards of a couple of hundred bucks.

Needless to say it was the dead of winter in the heart of the Adirondacks. The Adirondack Loj, the sort of hiking headquarters of the park, was near the base of Mount Jo. And Mount Jo is a blessedly small mountain—not quite three thousand feet to the summit. It’s an easy day hike to the top in the summer. And once there you get a great panorama for minimal effort, the lakes and forests and many of the marquee peaks in the park, including the state’s highest, Mount Marcy, spread out beneath you like a sublime painting.

There was a hitch: the stalwart photographers at the daily newspaper I worked for refused to go on the trek. So I drafted my wife, who had a nice 35mm SLR Nikon and also had some of that French-Canadian blood in her. Just after the New Year, as I recall, we drove up the night before from the Albany area. We stayed at a cozy (that is, no frills) chalet-style motel. The Loj, with its rustic bunkbeds upstairs and a common area with a huge stone fireplace downstairs, exceeded my expense account.

The next morning we sat through the workshop, watching the demonstration and listening to our guide explain how he circular-sawed the white ash to a rough shape, then soaked and bent the wood around a mold.

By early afternoon the temperature had risen a little; the thermometer on the corner of the log-style building said five below zero, but our guide reassured me that it was probably more like five above. The dozen in our group headed out across the field and past the ice-sheathed Heart Lake the short distance to the trailhead and started up Mount Jo. Our guide tried to give me and my wife poles like the others were using, since it helps to steady you on the snowshoes. I told him that we couldn’t carry them since I needed to take notes and she needed to shoot photos. He seemed incredulous.

As we neared the top of the mountain, ice buried the rocks, and we had to almost crawl up, bent forward. At one point my wife needed to insert a new roll of film (remember that?). And when she was doing it, it was so cold that the film cracked! Somehow she got one in, and when we finally reached the summit in late afternoon after a two-and-a-half hour ascent she took a yeoman’s series of photos of three or four in the group looking out over the vista of God’s creation.

On the way down the mountain our guide said we should glissade, which is an elegant way of saying slide on our butts! Which we did most of the way, over roots and rocks, descending in about half the time.

Two decades later, after moving back east from San Francisco, the urge to hike the winter woods struck again. This time we went to a cross-country ski center that also has separate snowshoeing trails. It was in the southern Adirondacks and only a few days before spring. But as any true Adirondacker knows, winter camp, as the old soldiers who fought in these parts two centuries ago used to call it, doesn’t end until May 1.

The center was crowded with out-of-state cars, especially from Jersey and Connecticut. That’s the other downside of skiing, at least for me and my wife—the après-ski scene. Now the downhill scene seems to have infected cross-country skiing, which is what everybody else was here to do that day except for us.

After paying the entrance fee and renting some snowshoes, we entered the trail behind the lodge. The sun was bright, the air was milder than our excursion up Mount Jo, about thirty degrees warmer, but still crisp. And we had this part of the forest all to ourselves! There was a stream that had thawed, it was quiet and peaceful, the pines hung patiently with their bright white loads while the stark dark trees and the dull white birches stood guard, and the only sound was our squeaking steps as our snowshoes sank into the powder an inch or two. We walked on and on through the still, white-shrouded woods, like Robert Frost singing, “And miles to go before I sleep, / And miles to go before I sleep.”

So I never downhill skied, and my cross-country skiing days are long gone. But my wife and I still have snowshoeing. And it’s not just the only alternative, a life’s consolation prize. The Magic of Walking, a book I own that was published in 1967, points out that while a cross-country skier may go faster, “the man on snowshoes enjoys the same exhilarating air and dazzling views and more time to savor them.”

After a couple of hours of snowshoeing my wife and I went into the lodge. We shed our tech jackets and had a bite to eat and drank a beer at a table near the window and the sun shone in and warmed and lulled us, and we opened the windows a little and breathed it all in. Après-snowshoe didn’t seem so bad, after all.