by James Stevens Curl (May 2023)

View of Christ Church, Spitalfields (East End Series), John Allin

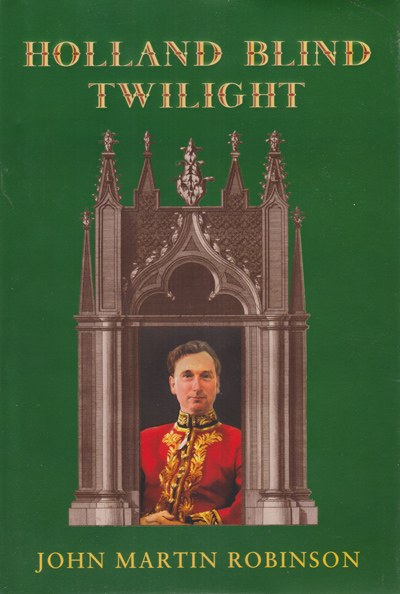

A fetching photograph of John Martin Robinson, “archetypal Young Fogey of the 1970s,” now Maltravers Herald Extraordinary at the College of Arms, Librarian to the Duke of Norfolk, and a Knight of Magistral Grace of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, graces the front of the wrapper of this little book, the second volume of memoirs following Grass Seed in June: the Making of an Architectural Historian (2006). Wearing his Herald’s uniform, Robinson looks out at us, framed by the ninth frontispiece for Batty and Thomas Langley’s Gothic Architecture (published 1747) giving an enticing flavour of the slightly camp contents, mingled with much Catholicism and name-dropping, lurking between the covers. It is all spiced with waspish asides and assessments certain to cause much gnashings of teeth in politically-correct circles inhabited by virtue-signallers pretending to be “caring,” but actually only interested in self-advancement.

“Historic buildings are more worthwhile than people” is one choice statement, and one with which I have a great deal of sympathy: however, it reminds me of a remark made by the Revd Henry Croyland Thorold (1921-2000), who upset the “cliché-spewing Bishop of Derby” by booming at a meeting, “church buildings are FAR more important than people!”

Robinson was one of a devoted set of conservationists who saved one of the finest buildings by one of England’s greatest architects when it was abandoned to its fate: I refer to Christ Church, Spitalfields (1714-29) by Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), situated “over an invisible border in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, then run by one of a cartel of incompetent, doctrinaire, Labour councils whose educational, town-planning, social and economic policies kept generations of inner city Britons in conditions of backward poverty, ignorance and misery for decades after the Second World War.” Robinson discovered that “many 1960s/1970s councils actively discouraged the restoration of Georgian urban areas as they did not wish them to be taken on by people who might not vote for them, a gerrymandering policy also pursued at that time by neighbouring London boroughs … which let listed houses rot rather than sell them for rehabilitation. Outside London was even worse and Liverpool systematically destroyed two thirds of its Georgian ‘West End’.” In my experience that assessment is not inaccurate, for decades ago I stood aghast in parts of Liverpool and Stepney when destruction was widespread: what replaced the wrecked fabric was a dystopian nightmare that has not lightened or softened at all over the years.

From 1974 Robinson worked for the Historic Buildings Division (as did I from 1970 to 1973): he describes it as “a reactionary cell embedded in the Marxist GLC Architects’ Department,” again a statement that seems to me to be spot-on. However, nemesis for the Division came from the Right, not the Left: Ken Livingstone’s “childish posturings” enraged Mrs Thatcher, who abolished the GLC (and therefore the Historic Buildings Division), with “dire long-term results for London, opening the way for a trashed skyline and a tide of third rate commercial and tourist tat.” Indeed it did.

On ecclesiastical matters Robinson quotes the Revd Anthony Symondson, SJ, (though calls him “Symdonson,” which is rather careless), who found beneath contempt the resolutely non-liturgical colours of turquoise and “Tango Orange,” badly-proportioned mitres, and “ubiquitous cliché of embroidered flames” favoured by those who embraced modern Anglican Kitsch. “Worst of all … were the School of Beryl Dean altar frontals” which Symondson saw as “public demonstrations of sub-Expressionist bad taste, a kind of English lower middle class female folk art” created by “dewy-eyed women dressed in fuchsia pink trouser suits.” Indeed: such “incongruous horrors that detract from every medieval cathedral and major church in the country” are all-too obvious in these dreadful times when the Church of England seems intent on spontaneously combusting itself.

Many of the persons Robinson mentions made positive contributions to the history of architecture, not least David John Watkin (1941-2018), who, to the consternation of some, in 1970 became a Fellow of Peterhouse, Cambridge, where his rooms were furnished in impeccable taste, with a predominantly Regency flavour. Like Monsignor Alfred Gilbey (1901-98), another personality who figures in Robinson’s book, Watkin believed that Chaos lay all around, and that it should be the duty of all those who care and have standards to impose æsthetic, moral, and spiritual Order: it was also clear to him that although it had once been the Classical architect’s aim to create Order out of Chaos, the Modernists created Chaos where once there was Order.

In 1977, the Clarendon Press published Watkin’s Morality and Architecture which outraged the Lib-Lab gerontocracy, especially paid-up disciples of Modernism. P.R. Banham (1922-88) denounced Watkin for displaying a “kind of vindictiveness of which only Christians seem capable,” S. Bayley called the book an “addled, sly, knowing, superior, rancorous smarmy, sneering stinker”; and S. Lyall referred to a “waspish and spiteful” text. Watkin’s objections to the “secular moralising” of Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-83), who viewed the world through Bauhaus-tinted spectacles, disturbed a hornet’s nest of criticism: the obtuse did not get the point at all.

That important book, undermining many of the bogus arguments underpinning grand narratives of Modernism, and slaughtering many sacred cows and entrenched beliefs, came under hysterical attack. The author and his work were subjected to vulgar abuse by those with vested interests in continuing to promote the Cult of Modernism, so the vicious denunciations of Watkin’s slim volume were for all the wrong reasons. Robinson correctly says that the book was met with outrage by the architectural establishment entrenched in the Royal Institute of British Architects (an outfit he reasonably describes as “a trade union for mediocrities posing as an educational and cultural charity”) and by the bullies who run “Schools of Architecture.” Recent antics and behaviour of figures in the RIBA and those associated with its boring Journal say it all.

Robinson’s style and judgements led to his being sued for libel “by an ageing modernist architect” who objected to descriptions of what I reckon is perhaps an over-rated house he had designed. That “ageing modernist” used to stuff his Modernist beliefs and adulation of deified Modernist architects down the throats of unfortunate students way back in the early 1960s. I know, because I suffered from such attempted indoctrination (which did not work on me). The writ caused Robinson a huge amount of distress and anxiety, but he was saved through the generosity of his publishers.

However, he does not pull his punches or spare those of whom he disapproves: his criticisms are still very powerful, and not watered down at all following that experience. For example, his rancid opinion of Raine Spencer (1929-2016) is given here: “she was completely uneducated and a ridiculous figure in her crinolines and swept up hair, like those dolls the Hyacinth Bucket-type of New Yorkers use to hide their telephones or lavatory brushes.” He tells us that the London Library catalogue of the Althorp Collection has been liberally annotated in pencil with “Sold by the Harpie” against every missing art work, which is pretty strong stuff. Robinson “enjoyed the story” that when young she did not marry Peter Daniel Coats (1910-90), the garden writer (Robinson carelessly calls him ‘Coates’), not because “he was obviously gay,” but because “she didn’t want to go through life” being called Raine Coats.

All in all, this is an amusing, often acidulous, read, although Robinson’s avoidance of necessary hyphens and other eccentricities of punctuation sometimes irritate, as do his sloppy spellings (Maddison Avenue, forsooth!). In my own case, I knew many of the personalities mentioned, including Watkin, Gavin Mark Stamp (1948-2017), and Robert (‘Bob’) Chitham (1935-2017), former submarine commander, author of a fine book on Classical Architecture, who now lies in the little churchyard of St Leonard, Yarpole, Herefordshire.

The world is the poorer for their passing, but the richer for the contributions of quirky sensibilities like Robinson’s, becoming rarer and rarer in these dispiriting times.

This article was previously published in The Critic, September 12, 2021.

Table of Contents

Professor James Stevens Curl is the author of Making Dystopia: the Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism (2018, 2019, Oxford University Press), which forensically dissects the rise and survival of architectural Modernism with devastating clarity and logic, so has been subjected to avalanches of personal abuse for daring to question what is undoubtedly a fundamentalist quasi-religious Cult of brainwashed believers.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link