Automation Wins

by Albert Norton, Jr. (May 2023)

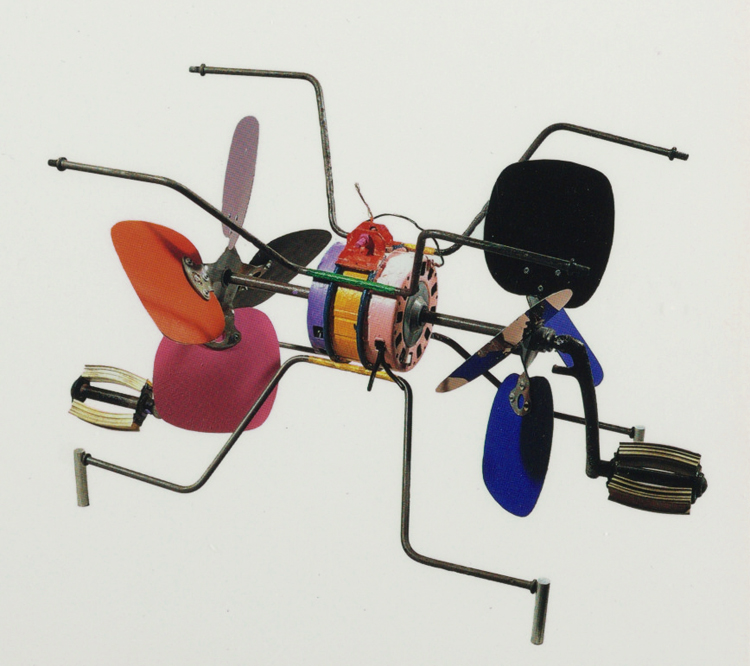

Twin Bloom—R.O.C.I. Tibet, Robert Rauschenberg, 1985

The Glass Bees is a prophetic and unsettling novel. A proper appreciation requires understanding that it was written in 1957: well after the worldwide conflagration of WWII, but before advent of the internet and explosive advances of information technology employing algorithmic automation. Jünger was at the time of its publication 62 years old, a veteran of WWII and WWI before it, both on the losing side.

The novel seems to have enjoyed a renewal of interest in recent years, partly because of its eerie prescience. And yet, the point of it isn’t to extrapolate technological advances, nor to glorify the past. It doesn’t so much recall us to an earlier way of thinking, as hint at something lost that we cannot perceive now. It’s as if we have arrived so late to the party that the revelry has subsided to the gathering of coats and half-whispered “good nights.”

Something has gone out of the world. We know this but we hardly know what it is—or was—instead we sense it only indirectly, like a fast-fading after-image where a moment before stood your lover, as in a dream, mustering a half-smile before slipping out of your life forever.

How does Jünger re-create for us this feeling of something lost? His first-person narrator is Captain Richard, a former cavalry officer, concerned with horses in the first of the twentieth-century earth-shaking conflicts, and then their replacement with tanks, in the next. The story twines the advances in technology with the loss of something more important, which might be described as “honor,” or even “dignity.” Horses to tanks. Inventiveness to automation. Idiosyncrasy to conformity. All oriented to a pervasive and oppressive default to scaled mechanization.

Indeed, there is an inverse relationship between the striving for human perfection, and the striving for technical perfection. “Technical perfection strives toward the calculable, human perfection toward the incalculable.” Though we can pursue only one of these competing courses, we don’t really choose. There is an inevitability to the mechanistic drive. “Accidents are the result of injuries that took place long ago in the embryo of our world … The shot was fired long ago.”

The drive to technical advances is evinced in warfare technology, of course, but also in commercial applications which draw us in so that we are fully absorbed in the simulacra of technological entertainments or engagements. Today that manifests in zombified iphone texters walking down any street in the modern world, oblivious of others and so always in near-collision with them. Or a subway car with every seat taken, entirely silent but for the movement of the car, every head bowed not in prayer but in thrall to flickering images or words on tiny screens.

The story in Jünger’s book revolves around Captain Richard’s interaction with Zapparoni, a genius who zaps the consumers of his technology with isolating and dehumanizing tendencies. You’ll read “Zapparoni” but think of some combination of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and whatever wizards are behind the Oz of the Disney empire. The Glass Bees was published long before the internet or the ubiquity of computers, but subsequent to brisk technological advances in means of warfare, and transportation, and perhaps most significantly, radio followed by television.

We like to engage in hand-wringing about where all the technological advances are taking us, but we should really make a distinction between particular doo-dads and the principle behind technology in general. New gadgets certainly require change to the way we live, pivoting us almost daily as innovation follows upon innovation so that change evokes change. The backdrop to a particular innovation is not stasis, but rather a blur of innovations from which the particular emerges briefly, like the soft pfft of a breaking bubble in hot mud, immediately subsiding to be replaced by another, and another. Technology is both medium and product, in other words, and so the substrate principle is change for the sake of change, rather than the ultimate good of human beings in whole relations of love, and friendship, and belonging, and reverence.

Technology is not just a succession of life-altering extensions of human capability. It means a change in human thinking. The key is automation. Algorithms govern machine processes, and machine processes govern human algorithmic activity. Machine “thinking” influences human thinking. Our instincts are to find scalability of process in nearly any undertaking. How can this not diminish us? Like with Zapparoni’s workers, who require policing in subtle and unsubtle ways, people are increasingly instrumentalized and harnessed like machines.

Jünger narrates Captain Richard as a self-aware anachronism, one who instinctively resists progress of the machine, though it leaves him in penury. He thinks of himself as a man belonging to an earlier time, a time when his military academy mentor Monteron was still alive, exerting an authority organically rooted in honor and a fullness of being unmatched in this latter era governed by contract; by piece-work; by repetition. For Richard, the shift to modernity—out with the horse, in with the tank—creates an increasingly dismal world. If he makes peace with it at all, it is solely for love of his wife Teresa. “If … I still had something of a home, it was with her.”

Your reviewer was born in the year The Glass Bees was first published. It’s hard not to see, in the intervening 65 years, a deterioration of humanity into products of materialist conditioning that Marx imagined human beings always to have been. Extrapolating backward from 1957, and with the gloomy light cast by the mid-century wars, this has been a development long in the making. One would have to be of Monteron’s 19th-century vintage to begin to understand what has been lost, without the aid of vision like The Glass Bees.

The protagonist, Captain Richard, himself perceives but dimly, narrating in snatches of observation the reader then pieces together. He is clear-eyed about his own limitations, however, in contrast to the requirements of the new world. This discharged cavalryman is now doubly anachronistic with respect to his own employability, yet he worries for the current generation’s prospects more broadly. Of the post-war young, “They had been born into an atmosphere of insecurity and had never known the absolute assurance of a Monteron.”

Now about the bees. Automatons, little robots, but the point is not gee-whiz technology. The point is automation of human beings. Not just that we’re increasingly dependent on machines and become more like them—though that is certainly ominous enough—but also that the automation is a collective undertaking. As with natural bees. Studying the robotic bees, Captain Richard thinks: “I cannot say what astonished me more—the ingenious invention of each single unit or the interplay among them.” Indeed. What astonishes you more: the capabilities of a computer, or their interlinkage in the internet? Automation in things and processes begets automation of human beings begets a collectivist mindset. As with bees, one is first member of the hive, and only secondarily a discrete unit of consciousness.

This shift is accompanied by a sense of unrest, of discontent, of anxiety, of continual engagement with negation. We might call it “alienation,” not the variety Christians ascribe to breach of relationship with God, but rather the Marxist version in which a false consciousness with regard to power structures keeps us grindingly pulling at the traces, for another hour; another day.

The sense of alienation follows upon refusal to accept the givenness of things: the island of individual consciousness; the inevitability of exasperation at times with our fellows; one’s very sex. In a world in which all is man-created, including Zapparoni’s creation of “thinking dead matter” (we would say “artificial intelligence”), the givenness of things is a discardable notion; we have “a different attitude toward creative authority.” We are ourselves the sole creators, and so all is artificial; there is no “natural” to which we stand in distinct relation. Our relation to what we call the natural world is entirely exploitative, we think. A quarry for our construction materials, like robotic bees that extract nectar but do not reciprocate with pollination.

Where does all this lead? It can only lead to totalitarianism. Under the Zapparoni regime, people must be eliminated as they are currently self-conceived, just as horses had been eliminated from relevance after the horse-cavalry days. The Zapparoni/Gates/Klaus Schwab mindset “want[s] units to be equal and divisible, and for that purpose man had to be destroyed as the horse had already been destroyed.” Captain Richard despairs of joining the Zapparoni machine because though “today one had to be part of the game,” the game is destructive. “The closer one stood to the center of the game, the less significant its victims became.”

In this world things have price but not value; people become widgets in the machine; words lose their meaning and shape-shift to serve ideologies; and some words, like “honor” and “dignity,” become ludicrous.

Table of Contents

Albert Norton, Jr is a writer and attorney working in the American South. His most recent book is Dangerous God: A Defense of Transcendent Truth (2021) concerning formation of truth and values in a postmodern age; and Intuition of Significance, a 2020 work weighing the merits of theism against materialism. He is also the author of several award-winning short stories, and two novels: Another Like Me (2015) and Rough Water Baptism (2017), on themes of navigating reality in a post-Christian world.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast