by Samuel Hux (August 2019)

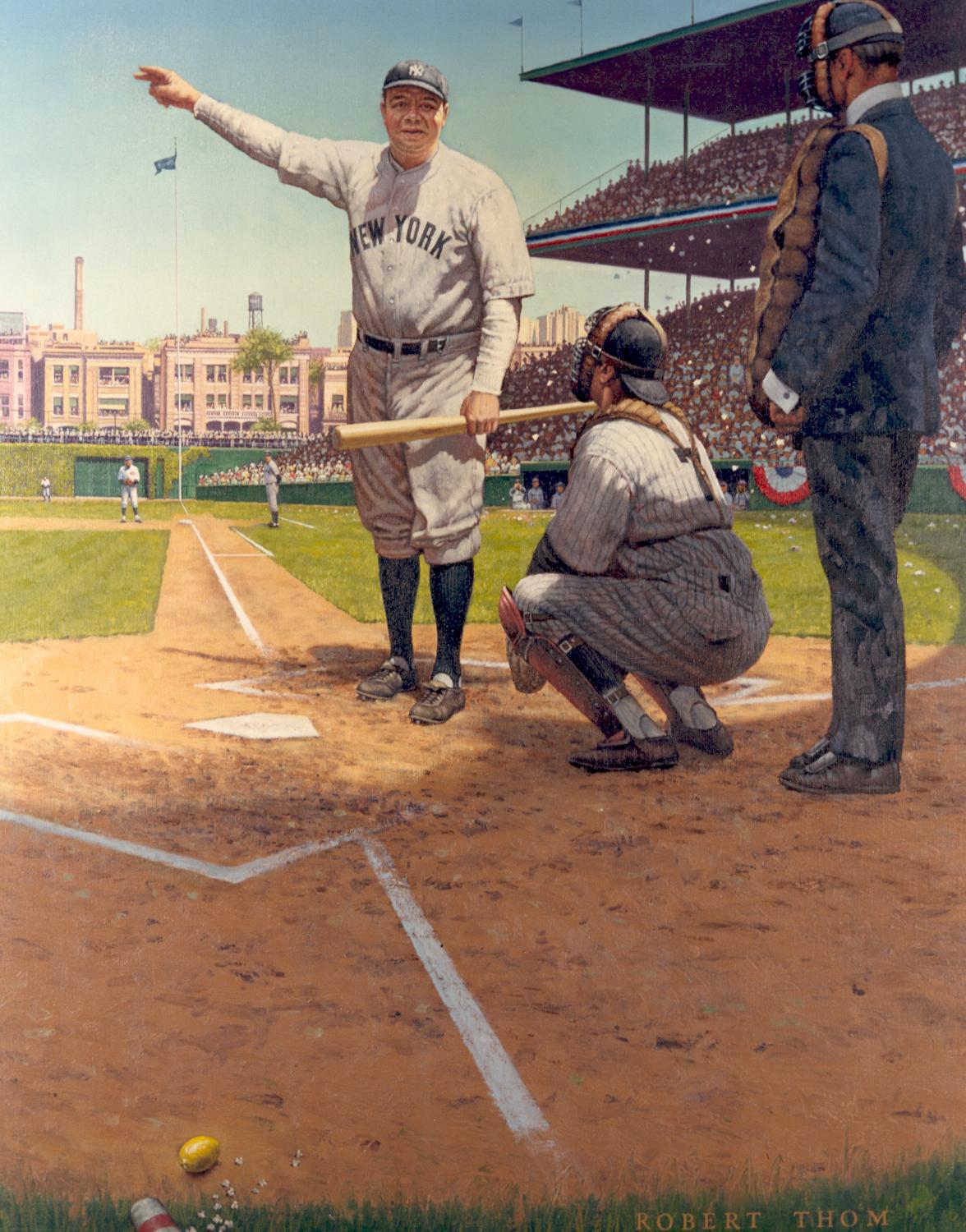

He Called It, Robert Thom, 1932

Parents named Smith should never name a kid “Robert.” The black-and-white photo on the jacket of Baseball in the Afternoon suggests a redhead, but he couldn’t be called “Red” for obvious reasons, given the fame of the sports columnist Red Smith. So, in spite of his productivity, and the recognition he received from peers during his lifetime, this Robert Smith is, today, practically anonymous. Try to find him among the dozens of prestigious Robert Smiths on Wikipedia and he apparently never existed. The New York Times obituary, after he died in 1997 at the age of 91, is too skimpy to bother with—telling us he wrote some novels and a couple of baseball books without mentioning the one noted above. What an injustice: as Ecclesiasticus in The Apocrypha instructs us, we have a duty to honor the dead. The ethics of memory, I call it.

His earlier book, Baseball, 1947, revised 1970 (something amusing about such a simple and proud title by someone of the simplest of names), is a great, great achievement. You will find little there about who won the Series in what year, who led the league in you-name-it. This is a social-cultural history of baseball, essentially a series of bio sketches of figures who represent this or that aspect of the game, all arranged chronologically and coalescing into a collective narrative. That it was dedicated to the poet Conrad Aiken is probably irrelevant—but not to me: Robert Smith had class. His last book, appearing in 1993, is neither social history pleasantly disguised as baseball lore (Donald Honig’s Baseball America), nor sustained thesis (William Curran’s Big Sticks), nor detailed chronological recreation (Robert Creamer’s Baseball in ’41baseball fan (which phrase I’ll rigorously, and even apodictically, define shortly).

Baseball in the Afternoon is part history, but with no strictly chronological order: one thing sort of casually but seamlessly leads to another. It’s part memoir: young Boston Irishman discovering the Red Sox before such immortals-to-be as Babe Ruth and Waite Hoyt are shipped to the Yankees; adult writer recovering a kind of youth in sandlot softball. (“Actually, softball resembles original baseball more closely than the official game does.” True.) But modest and respectful before his subject, Smith disappears (but for his voice) for the longest stretches of the book—so it’s all the more reassuring, and he’s all the more welcome, when he reappears briefly to note, with absolutely no tone of name-dropping, that such and such a story was told him by Hoyt, or Arlie Latham (third baseman of the 1880s and ‘90s), or George Weiss (one of the few executives in the Hall of Fame), or Cyclone Joe Williams of the Negro leagues, and so on. And, incidentally, anyone who has ever suspected that the famous host of the stars Toots Shor was a posturing fraud, boorish always, obsequious before the mighty, is right. Smith was there when a vacationing restaurateur tried to introduce himself to Shor, Shor dismissed him with “I don’t know ya!” and vacationer’s wife threw her highball in Shor’s face. “The bartender . . . leaned close to me and muttered, ‘Too bad it wasn’t a Bloody Mary.’”

Read more in New English Review:

• All’s Well and Some Discontents

• J’aime la Tour

• Isn’t it Amazing?

Does this sound merely chatty? Then I mislead. It’s conversational—and being so it makes you want to join in: Well, I knew that Charles Comiskey was the first infielder to play off the bag, but it had never sunk in that the shortstop had to cover practically the entire infield, was a kind of rover. But can you tell me how early the batting order evolved, the exquisite logic of lead-off, clean-up, and all that? And being conversational it makes you want to argue: No! for all his virtues Frankie Crosetti does not belong in the Hall of Fame. And since the book is one half of a conversation (when “scholarly” defenses are down), screwball opinions like that one are part of the charm.

Baseball fans like to talk. But not all who talk about the game are fans. The leftfielder and lead-off man who said in an interview “I don’t care about no Jackie Robinson; I care about now” was no fan. (I think it was the next year that the baseball gods cursed him with a .285 on-base percentage, a scandalous figure for a lead-off man.) Fans are passionately interested in tactics and strategy, yes (“How the hell could he throw a change-up in that spot?” or “Bat him in the eight hole for Chris’sake—he hasn’t got the power for sixth!”), but they are also necessarily passionate about history, whether it’s chronological or whether one thing casually leads to another. If you never wonder who was the greatest (usually with a presumptive prejudice that in the past giants walked on the earth), if you never wonder, for instance, which was the finest pennant race, then I doubt you’re a fan—only a follower—and not likely to be interested in Bill James’s The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works or Dave Anderson’s Pennant Races: Baseball at its Best. The above requirements admit of no exceptions.

Anderson celebrates sixteen pennant races between 1908 and 1993—which certainly has a certain poignancy: since the NFLization of baseball in 1994, with three divisions per league, meant that “wild-cards” (read “pennant race losers”) had a chance to make the World Series, then 1993 was “The Last Pure Pennant Race.” Now, one can quarrel with Anderson’s selection of races—and since one can I will. What about 1945, when Hank Greenberg, back from the Army (after being the first player drafted), homered against the St. Louis Browns to insure the Detroit Tigers a game and a half victory over the Washington Senators? Or perhaps 1944 is a better selection: when the last place Senators beat Detroit on closing day to help the Browns to their only pennant, one game over the Tigers. What 1945 has to recommend it is the fact that it was the first World Series I was aware of. And how can one quarrel with Anderson’s modesty? “If one or two of your favorite races isn’t there, maybe it’s my mistake, but I tried to choose the races with the best plots.” How can one quarrel? Easily. Best plot? Then why not the 1915 Federal League, the outlaw thumbing its nose at the establishment—when the St. Louis Terriers finished one percentage point, but no games, behind the Chicago Whales, and the third place Pittsburgh Rebels finished a mere half game out?

Nonetheless, Anderson is very good at plot: So and So works the count to 3 and 2, What Not on second is a slow runner, Old Buddy on the mound is visibly tiring . . . But perhaps he’s most entertaining when he yields to the same anecdotal condition that graces Smith’s book. Joe DiMaggio returns from injury half way through the 1949 race with the Red Sox; New York gives him a “Joe D. Day,” during which his mother ignores Joe and walks past him to hug his brother Dom of the Sox (“I saw Joe yesterday. I hadn’t seen Dominic”); Joe concludes his acceptance speech with a tribute to Boston: “They’re a grand bunch too. If we don’t win the pennant, I’m happy that they will.” This touches a chord in me. When I was a kid in the sticks, I was a Yankee fan and a Red Sox fan (Joltin’ Joe and The Splendid Splinter), happily oblivious to the wisdom that it’s metaphysically impossible to be both. When I say that fans love history, I mean in part that they love where it touches them, memory of self at one with memory of event.

Even better than Anderson at telling a story is Bill James—but a different type of story. Rather than lively action summaries, brief biographies (of shortstop George Davis, 1890-1909, who is not in the Hall of Fame, Joe Tinker, 1902-16, who is, Ernie Lanigan and Lee Allen, early baseball historians and sometime librarians of the Hall, and others), and narratives of Hall selection machinations (fascinating, but too complicated for easy recapitulation). James I’m sure would appreciate being called a good storyteller, but I’m not sure he’d welcome the judgment that old-fashioned narration is his strong suit rather than his statistical obsessions (not a word he’d use). His ten double-columned page bio of Ernie Lombardi in the second Historical Baseball Abstract is worth the price of the book. He can be somewhat condescending toward “older baseball writers” who wrote “from their memory and a few clipping files . . . They got a lot of things wrong.” One of the older writers he singles out is Robert Smith! I’m sure he did get some things wrong. So what? One does when one writes out of a loving personal memory. When James makes like a cliometrician, he often ignores his own caveat that you must be careful how you interpret statistics. And a stronger caveat ought to be how you create them: James has a system he calls “Hall of Fame Standards,” whereby Willie Mays is the greatest player of all time (84 out of possible 100). That may not be exactly absurd, but it is flatly wrong! (Disagree? Write me a letter.) Any system of measuring talent which does not find that George Herman Ruth (who was on his way to Hall of Fame distinction as a pitcher before converting to Home Run King) was the greatest baseball player who ever lived, self-destructs. There are self-evident truths.

You might say that one theme of The Politics of Glory is Phil Rizzuto’s lack of qualifications for the Hall of Fame, except that in a sense it is the theme: James calls Rizzuto “the central figure in the book.” Since it is now ironic that Rizzuto made it the year that James published, I might add that James protected himself: after focusing on Rizzuto’s “common skills” for five full chapters, he concluded the book largely completed in 1993 (there’s that date again) with “A last note: On February 27, 1994, the Veterans Committee elected Phil Rizzuto to the Hall of Fame. He won’t be the worst player there.”

Rizzuto and PeeWee Reese have been thought in the same thought since the 1940s, and after Reese alone was inducted in 1984 many (including Reese) thought The Scooter had been done an injustice. Not James. So, some comments: If you divide careers into 150 game appearances per season (that’s arbitrary; 145, 140 would do as well) instead of comparing career totals in lumps as James does, you’ll find that Rizzuto, as an offensive player, was comparable to Rabbit Maranville (inducted 1954—justly so, finally). Indeed, except for Rizzuto’s higher batting average (.273 to .258) he was Maranville. Of course he wasn’t Maranville in defensive range (put-outs and assists). In fact, few shortstops approach the Rabbit. His contemporary, Dave Bancroft (who James thinks doesn’t deserve his Hall plaque), and a step behind that Ozzie Smith (who was inducted in 2002). James makes much of Reese’s better offensive numbers (though slightly lesser BA, .269) and, indeed, Reese hit six more homers per year (150 games) than Rizzuto and ten more runs batted in. On the other hand, Rizzuto (“not truly comparable to Reese,” James assures us endlessly) was practically Reese’s twin defensively. Rizzuto: .968 fielding average, 290 put-outs per year, 421 assists, 24 errors. Reese: .962, 286, 424, 28. Rizzuto was Reese, or the other way around. Almost: for Rizzuto averaged 110 double plays to Reese’s 87. (Rizzuto also has the advantage of Ozzie Smith here as well as Maranville and Bancroft.) If one argues that Rizzuto had the advantage of superb second basemen, it’s worth noting that none of the four regulars with whom he played—Joe Gordon, Snuffy Stirnweiss, Jerry Coleman, Billy Martin—were quite as successful in DPs before or after teaming up with Rizzuto. (You could look it up.) And Reese’s partners—Billy Herman, Eddie Stanky, Jackie Robinson, Jim Gilliam, the first and third Hall of Famers—were hardly clods. Stan Musial and Al Schoendienst could never adjust to Marty Marion’s absence from the Hall. And indeed, Marion’s defensive numbers make Rizzuto, Reese, and Marion look like triplets . . . almost. Marion had a .969 fielding average, his put-out figures comparable to the others’, but with around 40 more assists per year. He would have to be given the edge if he did not like Reese trail the Scooter in double plays by a wide margin. All things considered, Rizzuto was the champ. The Red Sox certainly knew it.

If I focus on the Rizzuto story, it’s only because James’s polemical emphasis is like an invitation. For all of James’s Scooter-fixation (and there are other instances: comparing Rizzuto’s power numbers to Vern Stephens’s is like lining Ozzie Smith up against Cal Ripken), James is dead right more often than he’s wrong. No, Chick Hafey, Freddie Lindstrom, etc., don’t belong in the Hall of Fame. Which doesn’t mean that a couple of dozen who aren’t don’t—like Indian Bob Johnson of the old Athletics, who is Jim Rice, whom James projected in the Hall by 1995 (he made it in 2009). And one might mention (I will mention) the absence from the Hall of Dom DiMaggio, who, as Tom Clavin notes (The DiMaggios), had more hits during his career as regular (1940-42, 1946-52) than anyone else during those years, including his brother Joe , Stan Musial, and Ted Williams, and scored more runs than anyone but Williams.

For all his virtues, I must say I occasionally worry about James’s values. After arguing convincingly that the ancient shortstop George Davis belongs in the Hall—indeed has, according to James’s cockamamie “Hall of Fame Standards,” the highest score of anyone outside—James concludes thus, “George Davis is dead. He is forgotten. I can’t see that it would accomplish a hell of a lot to vote him a plaque now.” This from a fan? Far be it from me (but not too far) to speculate seriously on James’s political persuasion (but if he isn’t an orthodox liberal, I’ll eat your beret). I sometimes wonder if baseball fans are not by nature conservative, culturally so at least, and sometimes think the only real liberals who are true fans have to be literary intellectuals bemoaning the tragic history of the Boston Red Sox (until recent years) or the Chicago Cubs (until even more recently). In any case, what a bizarre notion, that you don’t honor the dead! Fans have to. That requirement as well admits of no exceptions.

I think I should offer some explanation for so much on Bill James in an essay which began as a celebration of a man named Smith. It has little to do with this book, but rather with some judgments in his revised edition of Historical Baseball Abstract. Hank Greenberg is only the eighth greatest first baseman? Nonsense! Only Lou Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx were greater. This is, in effect, no less than punishment for Greenberg missing four and a half seasons while in World War II combat. I will not enter the controversy over centerfielders, for fear of apoplexy. But Joe Morgan is the number one second baseman? He was better than Eddie Collins, than Nap Lajoie, than Charley Gehringer? None of them surpassed Rogers Hornsby. Of course, Hornsby was not a great fielder, just an adequate one. But that does not matter when you consider how he hit, is just a damned perversity to argue that it did, and there is no real argument supporting James’s elevation of a very good player with a .271 lifetime batting average. If you hit .358 lifetime (and would have averaged higher if you had not played until age 41), with an on-base percentage of .434, and, dividing your career into 162 game seasons (the Baseball-Reference.com method), with 22 homers per season and 114 runs batted in and 113 runs scored, and during a decade ending when you were 33 compiled batting averages of .370. .397, .401, .384, .424, .403, .317 (what happened!?!), .361, .387, .380 (that is, over .400 three times, and under it by three points another time), then you are immortal and there is no argument about it. Case closed, slammed, shut the hell up.

Danger of apoplexy or not, I do have to say something about centerfielders. Willie Mays was indeed a great ball player whose only weakness was that he was a double-play machine. But, how in God’s name, does he rate higher than Ty Cobb?—as a ball player I say, not as a human being, for the racist Cobb would have spoken to Mays as an inferior. Mays, as a ball player, was superior to Cobb in only one talent, home run slugging. To squabble over who was a better defensive outfielder is petty, foolish, a waste of time, since they were both exceptional. Offensively, per Baseball-Reference.com, Cobb hit .366 to Mays’s .302, scored 120 runs to Mays’s 112, stole 48 bases to Mays’s 16, and with only 6 homers to Mays’s 36, drove in the same number of runs: 103. Let’s put it another way. Given the perennial Willie Mays-Mickey Mantle debate, compare Mays and Mantle: BA .302 and .298; runs 112 and 113; stolen bases 16 and 10; HR 36 and 36; RBI 103 and 102. A bloody statistical tie! Given this and their defensive talents, Willie and Mickey are twins. Is someone seriously going to argue that Mantle was Cobb’s superior (The Mick without any affirmative-action leg-up)?

Joe DiMaggio comes in fifth in James’s book, behind Mays, Cobb, Mantle, and Tris Speaker among centerfielders. I’m not going to compare Speaker and DiMaggio. Speaker was simply a different kind of player, a lesser Cobb, one who, like Cobb, could have as easily batted lead-off as third. But a comparison with Mays and Mantle is in order: great defenders all and, although speedy, their stolen base numbers are irrelevant since they played in an era of station-to-station baseball. Recall from above Willie’s and Mickey’s batting averages, power figures, and run production. Here are DiMaggio’s: BA .325, runs 130, HR 34, RBI 143 (!).

And while we’re at it . . . as long as people in my lifetime have made up all-time All-Star teams, the two locks for outfield have been Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, with the third name up for grabs: Speaker for a while, Joe D some said, Mays now a popular choice, although Hank Aaron, I think, has a better claim than Mays. Lest anyone nominate Barry Bonds, I say No!—after all, there was a real Aaron, not a steroid-Frankenstein monster. But I have always thought DiMaggio the best choice. He was a superb fielder, who didn’t have to make sensational catches because he was always positioned (governed by his superb baseball intellect) where the ball was coming down. His offensive statistics were simply superior to those of athletic geniuses like May and Mantle and, while Ted Williams may have been a better hitter overall, DiMaggio was a better batter, if I may invent a distinction. Williams would never swing at a pitch he didn’t like even if there were men on base waiting to be driven in but DiMaggio was mentally incapable of choosing not to advance a runner home. Nor is my choice a minority opinion. One of the virtues (no, the principal virtue) of Maury Allen’s Where Have You Gone, Joe DiMaggio? (1975) is that he includes lengthy endorsements of DiMaggio as the best, interviews not simply with team-mates from the Yankees but with “enemies” and rivals like Bob Feller and Hank Greenberg—Greenberg especially, whose nine-page quotation was nothing less than moving. And I value the opinions of greats like Feller and Greenberg far more than the assessments of professional opinion-purveyors like James of anyone else.

Perhaps DiMaggio is not rated as highly now since he played only 13 years—but I, a veteran myself, am not going to punish anyone for military service. And there is another figure to consider when evaluating Joe DiMaggio, which deserves a paragraph or two of its own.

Hank Greenberg was always adamant that the most important offensive statistic in his game was runs batted in. I agree. I know that there is a point of view which is embedded in some of the newer-fancier stats—that RBI are after all dependent on others, the people on base—so the honor should not accrue only to the one who drives them in. Okay. But men can be on base . . . and can be left on base. What you need is a clutch hitter. RBI are all about clutch hitting. And the honor accorded clutch hitting rightly does accrue to the one who does it.

An unofficial statistic which fascinates me might be called RBIEG: “Runs Batted in Exceeding Games”—that is, more runs driven in than games played over a full season. Big Sam Thompson did it three times in the 19th century, twice during the modern period (when pitching distance was stabilized in 1893). Since then, ten players have done it once: Hornsby and nine others (Jeff Bagwell, George Brett, Walt Dropo, Chuck Klein, Mel Ott, Kirby Puckett, Vern Stephens, Hal Trosky and Ted Williams). Four have done it twice: Hack Wilson, Manny Ramirez, Juan Gonzalez, and the now-forgotten Brownie Ken Williams. Greenberg did it thrice. Ruth and Lou Gehrig are at the top, Ruth with six seasons and Gehrig with five. Just below Gehrig, with four seasons were Jimmie Foxx . . . and DiMaggio. In just 13 campaigns, be it noted. (It ought to be noted as well the names of great sluggers who never managed this extraordinary achievement.) In any case, the competition among centerfielders is really between Cobb and DiMaggio.

And while we’re at it, once again—or I am—a digression which I cannot help but make. I don’t think Mickey Mantle was a better everyday player, all-things-considered, than Lou Gehrig, than Jimmie Foxx, than Hank Greenberg, than Rogers Hornsby, than Ted Williams, than Hank Aaron, than Stan Musial, or than Ty Cobb’s early rival the great Honus Wagner, and perhaps a few other for-instances, so consequently I don’t think—Bill James’s standards not-withstanding—that Mantle’s statistical twin Willie Mays was either. (Nor am I convinced that either of the twins was more valuable than Ernie Banks or Frank Robinson.) Another case—if only in my single judgment—slammed shut.

Read more in New English Review:

• Another Nice Mess: Synchronized Turkey-Vulture Projectile-Vomit

• Rag & Bone

• Reminiscences from the Music Scene in LA in the Early Eighties

There is some leeway, however, in another matter of opinion. Some fans, I confess, like to “philosophize.” (“The only game in which the purpose is to leave home, to force your way into alien territory, to go into exile as it were, and against odds and interference return home”—that sort of thing.) Some fans (Robert Smith is one) don’t. “It was not a religious experience. Not a sacred rite. Not a tournament of knights-errant—it was fun.” But the fine thing about the game—and Smith’s book—is that fun and philosophy are not at war. One can simply enjoy the tales about Pete Browning (a 19th century great); Hal Chase (who, if history were just, would have been with the 1919 Black Sox); Big Ed Delahanty (who disappeared, drunk, into Niagara Falls); Hoyt; Latham; Amos Rusie, the great Giants hurler pre-Christy Mathewson; Ruth; “The Only” Nolan (from the 1870s-80s, rumored to have pitched 30 shut-outs one year before reaching the bigs, where he was a losing pitcher); Lou Sockalexis (the tragically alcoholic Penobscot popularly thought to be the reason “Indians” replaced “Spiders” as the name of Cleveland’s major league entry—a name honoring Indian braves, by the way, just like “Redskins.” Why are so many intelligent people so stupid?); and dozens; and the skilled anatomy of the ethics of Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Or, while treasuring the outrageous humor the game inspires, one can still reflect in low key on the simple justice of come-uppance, as in the following Smith story.

Duff Cooley, accomplished turn-of-20th century umpire baiter (a “dedicated” one, Smith writes), hits a shot to deep center which even the speedy Bill Lange surely can’t reach. As Cooley rounds second with head down and nears third, umpire Joe Cantillon shouts “touch the base or I’ll call you out!” Cooley just knows he has a chance for an inside-the-park home run. Cantillon follows Cooley toward home plate and shouts “Slide!”—which Cooley dutifully does. “You’re out!” yells Cantillon. “What the hell you mean out? Where the hell is the ball?” “Lange caught it,” says Cantillon.

Robert Smith was a great baseball writer. His only equal, as far as I am concerned, was Fred Lieb, who pre-dated him a couple of decades. Lieb’s Baseball as I Have Known It (1977) is the same genre, which one might call “casual and stunning and fully engaging and always instructive reflections on a sport shared with reader by a gentlemanly conversationalist.” Sometimes Smith’s and Lieb’s books get jumbled up in my mind—which is a compliment to both writers, as you don’t confuse a Great with a So-So—so I could not recall where I read the most stunning revelation about Babe Ruth I know of, until I recently checked. It was Lieb (which I should have remembered since he spoke German), but it has Smith (mis)written all over it nonetheless, the sort of surprise Smith often shares (like the Cooley-Cantillon story above). “Once when Ruth and I were guests of the Gehrigs at their home in New Rochelle, I was surprised to overhear Ruth speaking to Mom Gehrig in German. He spoke almost as well as Lou Gehrig.” How many people have ever thought of the Babe as a bi-lingual American? Always one for the ladies, did the Babe flirt with Gehrig’s mother? Was the ex-delinquent more eloquent in German? Du bist wie eine Blume, gnädige Frau. I am as I write awaiting the arrival from Amazon of Robert Smith’s Babe Ruth’s America.

The following story I offer to Smith in sincere appreciation for his “tales from a bygone era” even though he’s no longer around to receive it. The Orioles are behind one run in the bottom of the ninth, bases loaded with two outs. Pat Kelly (an amazing .370 as a pinch hitter in his four years at Baltimore) works the count to 3 and 2 . . . then swings and misses on a neck-high pitch. Unperturbed in the clubhouse, he’s accosted by manager Earl Weaver: “What the hell are you smiling for?” “I smile because I walk with God.” “Well,” says Weaver, “I wish to hell you’d walk with the bases loaded.”

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast