by Theodore Dalrymple (December 2017)

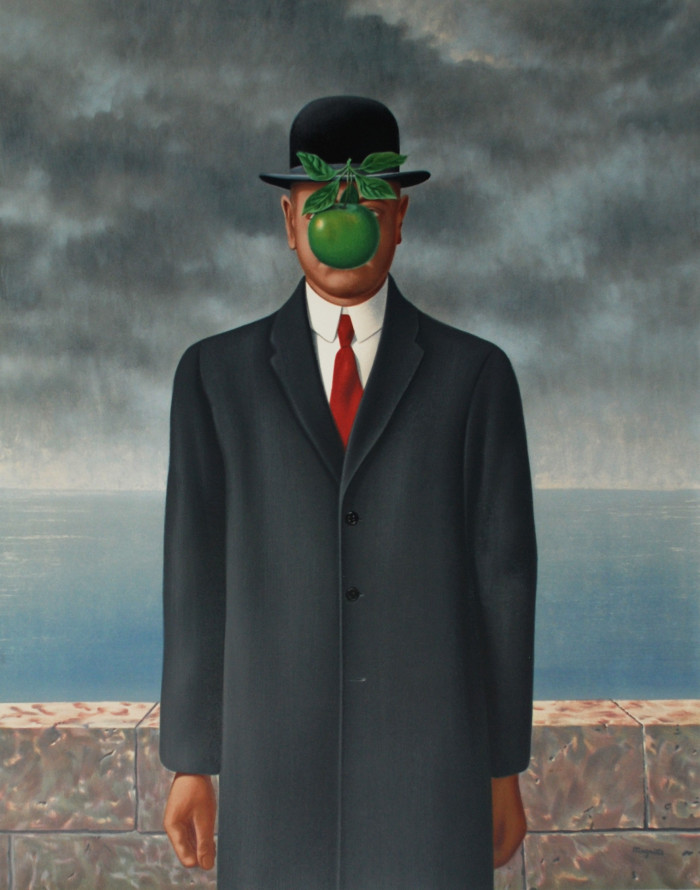

Son of Man, Réne Magritte, 1964

He who expresses his opinion in public must expect public criticism in return: but, speaking personally, I have found that the only truly hurtful criticism is that which is justified.

Some subjects provoke more criticism than others, if outright abuse can be called criticism. Among these is rock music, which is the nearest to being sacrosanct of anything that we now have in the western world. If you suggest that its ubiquity is anything less than a cultural triumph—that, on the contrary, it is a cultural disaster—you will soon be the object of execration the like of which you will never have experienced before.

I once wrote an article for a small but distinguished literary magazine that a rock ‘concert’ is like a fascist rally of libertinism, no doubt a strong way of putting it; the editor of the magazine was perfectly willing to print it, but said that he faced a revolt among his predominantly young staff. They said that they would resign en masse if he did so, and therefore he felt obliged to omit it.

Clearly, I had touched a raw nerve, rather as if I had attacked the character of Mohammed in Pakistan. The young people—educated young people, of course—must have felt that their very identity was under attack for them to react in this way, which they had never done before, not on any other subject. And yet the eagerness of young people to abandon their individuality at rock ‘concerts’ by uniting themselves in an hysterical quasi-communion with thousands of others, making gestures not very different from fascist salutes in response to a carefully staged event, brings Nuremberg inevitably to mind—or to my mind at least. I have always detested (and feared) such manifestations of individual submission to mass conduct, whether it be in football crowds, political rallies, prayers in unison or rock concerts. It is the voluntary abrogation of human freedom and therefore of responsibility; it is the beginning, though not the end, of brutality.

But of all the forms of music that I abominate, rap is by far the worst. (Incidentally, I dislike rock music not from snobbery, in case anyone should think it: I like popular music from many other parts of the world, most of which strikes me as less intrinsically savage, less nihilistic and uncivilised, more refined in emotion and attitude towards the world, than Anglo-American rock music. Popular music seems to me the one genre in which sentimentality is not only acceptable, but positively beneficial.)

Rap, by contrast, is the music of resentment, not of protest; its intention, it seems to me, as well as its effect, is to provide a justification in advance for impulsive, self-destructive and violent behaviour. Those who sell and promote it to a population already susceptible to its decerebrate message are far worse than mere prostitutes: they, not Socrates, deserve the hemlock.

Recently I wanted, for literary purposes, a line from a rap ‘song’ (rap being to music what a vulture is to a nightingale) to insinuate an atmosphere. At the suggestion of a friend, who had made a deeper study of these things than had I, I chose a line from an old ‘song’ by a group called Ni**az With Attitude, or N.W.A. No doubt the orthography including asterisks with which their name is written was intended ironically; but I suspect also that it is an illustration of the law of the conservation of taboo. At one time, the word ‘fuck’ and its cognates, with which their lyrics are liberally sown, would have been asterisked; and no one, I suspect, would now dare call the group, unironically, Niggers With Attitude. I am not in favour of the use of inherently insulting appellations, very far from it; but then I do not claim to be against taboos, because in my view taboos are both inevitable and beneficial. Therefore, we should choose our taboos with care; if they do not attach to one thing, they will attach to another. They can, in short, add or detract from the sum-total of civilisation.

The line I chose (after not very careful consideration, for there was an embarrassment of riches, so to speak) is from the song Real Niggaz Don’t Die, and is as follows:

I got a case of spittin’ in a motherfucker’s face.

I chose this line not because it was the worst available, but simply because it was more than sufficient to capture the nihilistic coarseness that I was after.

The line is worth some analysis: not in the sense that a line from Gerard Manley Hopkins, for example, is worthy of analysis, but because it reveals a mentality that is by no means confined to listeners (if that is the word for them) to rap music.

I got a case of: what does this imply? The locution suggests that the person using it is not in control of himself, that he suffers from something akin to a mental disorder, as defined in the ridiculous Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association. One can just imagine the criteria for diagnosis Facial Expectoration Disorder (the word ‘expectoration’ being so much more scientific than the word ‘spitting’), known also by its acronym, F.A.D.:

F.A.D. is diagnosed when at least two of the following are present:

i) Facial expectoration has occurred more than four times in the past six months;

ii) There have been repeated episodes over the past three years;

iii) It occurs in spontaneous response to perceived insult and is not premeditated;

iv) It occurs in the absence of physiological hypersalivation;

v) It is not a response to delusion or hallucination.

In other words, it is not really the spitter who spits; it is the condition, the disorder, the illness that spits. As Luther would have put it, here I spit, I can do no other.

No doubt the writer of the line would claim that his words were meant ironically rather than literally; but a sense of irony is not the first characteristic of those at whom the ‘song’ is most directed and who are most likely to like it. The resentful are generally unironic; for irony and resentment are mutually incompatible. Besides, when what is originally meant ironically is repeated often enough, its meaning becomes literal.

That its meaning is not really ironical anyway is suggested by the fact that the person spat at is a motherfucker. In other words, he deserves to be spat at, he is really the one to blame in the situation, not the spitter, and to spit at him is not really a choice but a kind of automatic, quasi-physiological response to him.

I don’t suppose there is a culture in the world in which spitting in someone’s face is not experienced as a deadly insult (though I am open to correction by social anthropologists, who may have found an isolated tribe somewhere in the world among whom spitting in the face is a declaration of love). Oddly enough, the response to being spat at in the face is an almost physiological one of anger; it is definitely a provocation, understood in law as such, though not everyone responds to provocation in the same way, and degrees of self-control vary not only from individual to individual, but from culture to culture and epoch to epoch. But at the very least it is unlikely that the writer of the words was unaware that spitting in people’s faces in the context that he wrote his ‘song’ is an excellent way to provoke retaliatory violence, and it is therefore difficult not to believe that he did not welcome, even glorify, this escalation.

This is made virtually certain by the other words and lines of the ‘song,’ which is actually but an incantation to self-pity as a justification for gross criminality.

If every nigga grabbed a nine

And started shootin motherfuckers it would put them in line

This is an incitement to race war, since the motherfuckers in question (a charming way to describe people, not far removed from describing them as vermin) are, ex officio, white. And so the obvious and oft-repeated, but nonetheless salient, fact that young black men in America are many times more likely to be killed by a peer from his milieu than by a white, is conveniently glossed over: for such a fact is an implicit call to painful self-examination rather to the self-indulgent pleasures of angry self-righteousness and total self-exculpation.

That all whites are motherfuckers is implied in the following beautiful stanza (if the word stanza does not over-dignify the lines somewhat):

So I’m letting them know how a nigga’s living

Taking from motherfuckers cause nobody ain’t giving

A damn thing to a nigga, a real nigga,

So I’m living by the motherfuckin trigger,

Cause a nigga ain’t afraid of being locked up

I’m out of luck, so why should I give a fuck?

This is a fitting and possibly predictable, though no doubt unintended, denouement of the Great Society: a thwarted sense of entitlement used as a justification for armed robbery and crime conceived of as rightful restitution.

It is usually absurd to demand logical consistency of lyrics, for a song is not a philosophical disquisition; but where the words are openly political, they invite analysis and criticism by political criteria. To proclaim that you are not afraid of going to prison and then to behave in such a way as is almost certain to land you there (if you survive long enough) is rather to deprive yourself of reasons for complaint when it does so—unless, that is, you really do believe that armed robbery, theft and murder are not crime but justice. Even if you do so, however, you can hardly call yourself out of luck when the very thing that you predicted would happen to you as a result of your conduct does happen to you. A man living under a dictatorship who opposes the dictatorial power in the knowledge that it will retaliate is not out of luck when it retaliates; he is, rather, a man who bravely took his chances.

None of this is to deny that men may be born into easy or difficult circumstances, or that ease and difficulty are distributed very unfairly. But it is the inescapable duty of every man to make the best of the hand that he is dealt, an obligation that continues through life. It is what being a human, rather than some lower animal, is. There are some hands, as every doctor knows, that are so overwhelming that nothing good can be made of them by those who hold them; but this hardly covers the case of the hypothetical chanter of this ‘song’; and indeed, there is hardly a good hand in the world that could and would not be spoiled by the attitude to life that it conveys. And is it conceivable that any group of people could raise itself up collectively by means of armed robbery and theft, even granted that in the past it suffered the grossest injustice?

There is probably no one alive who could not find cause for resentment which is in some sense justified: for no one can get through life without suffering some wrong, some injustice or unfairness (between which, incidentally, it is important to make the distinction). But the fact that resentment may be justified does not make it healthy or wise, or conducive to a proper or constructive engagement with the world, and is often itself a cause of much worse wrongdoing than that which occasioned it. To appeal, then, so brazenly to the resentment and sense of thwarted entitlement to a group already more than averagely susceptible to them, is about as irresponsible as it is possible for a writer to be.

But even without its extremely psychological harmful effect, even if it could be be shown that it had no such effect as I have imputed to it, the ‘song’ would still be unutterably disgusting in its crudity. That people should use their freedom of expression for this! It is enough to make one long for censorship: the censorship under which most of the world’s greatest art has always been produced. This is a subject to which I shall return.

_____________________________

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is The Proper Procedure from New English Review Press.

Please help support New English Review.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Theodore Dalrymple, please click here.

Theodore Dalymple is also a regular contributor to our blog, The Iconoclast. Please click here.