by Norman Berdichevsky (March 2021)

Royal Mail, John Armstrong, 1935

Visitors to Great Britain for the past three generations were immediately aware of two helpful, visible markers in the social geography of towns—the public telephone and the letter boxes. The former rapidly withered and ultimately disappeared, leaving few in the entire country due to the new technology of mobile phones. They exist today principally as memorabilia of a bygone age, restored by enthusiasts in their front yards or back gardens. Some are actually working phones while others serve as the new home of bookstalls, village noticeboards and artists’ showrooms.

The red telephone booth or “kiosk” used to be a familiar sight all over Britain, Bermuda, Malta and Gibraltar, other Commonwealth locations and elsewhere as in Argentina that had close business links with Britain. Today, they stand out as symbolic historic reminders of a rich past as part of the British empire. They are however still in common use in New Zealand. The classic British telephone booth had no place to sit down so you wouldn’t like to carry on a long conversation and prevent others from making an urgent call. The K6 model was the first red telephone kiosk to be widely used outside London. Many tens of thousands were deployed in virtually every town and city, replacing most of the existing kiosks. At their highpoint in 1980, there were an estimated 73,000 in use in the U.K. They have almost entirely disappeared since then. In Bexhill where I live, there is only one left that remains functional. During their most popular era, the phone booths presented a popular backdrop for tourists taking memorable photos. Some cities have retained a few just for their tourist appeal. The booth in front of Big Ben (below, L) is the most photographed in the United Kingdom

When I first came to live in the U.K. in the 1980s, the telephone kiosks had become the target of another group—prostitutes! The once proud telephone kiosk was being misused for their readily available advertising purposes, with cards stuck into every nook and cranny carrying their telephone numbers and occasionally their photos. City clean-up squads would periodically remove them in a never ending battle to stifle this method of “free advertising.” Attempts to combat porn graffiti called “tart cards” (above, R) were quite unsuccessful until the public phone booths simply were eliminated as the demand for them decreased.

When I first came to live in the U.K. in the 1980s, the telephone kiosks had become the target of another group—prostitutes! The once proud telephone kiosk was being misused for their readily available advertising purposes, with cards stuck into every nook and cranny carrying their telephone numbers and occasionally their photos. City clean-up squads would periodically remove them in a never ending battle to stifle this method of “free advertising.” Attempts to combat porn graffiti called “tart cards” (above, R) were quite unsuccessful until the public phone booths simply were eliminated as the demand for them decreased.

Royal Cyphers (the monogram or royal emblem of the reigning monarch) found on the face of all the red letter boxes and a fixed visible element in the social geography of the country. The one at the top the far right is the rarest—installed during the brief 8 month “reign” of the former Prince of Wales who took the title Edward VIII and then had to abdicate in order to marry the twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson.There are now only about 160 of them left.

The town of Bexhill, the site of this study of letter boxes is located on the coast of East Sussex, where I now live. It made headline news for its striking municipal exhibition hall built in 1935 in the town’s center which was hailed as the UK’s first public building constructed in the “Modernist” style, the De La Warr Pavilion. This pioneering structure of steel and concrete provided accessible culture and leisure for the people of Bexhill, regenerated the site, and attracted many visitors.

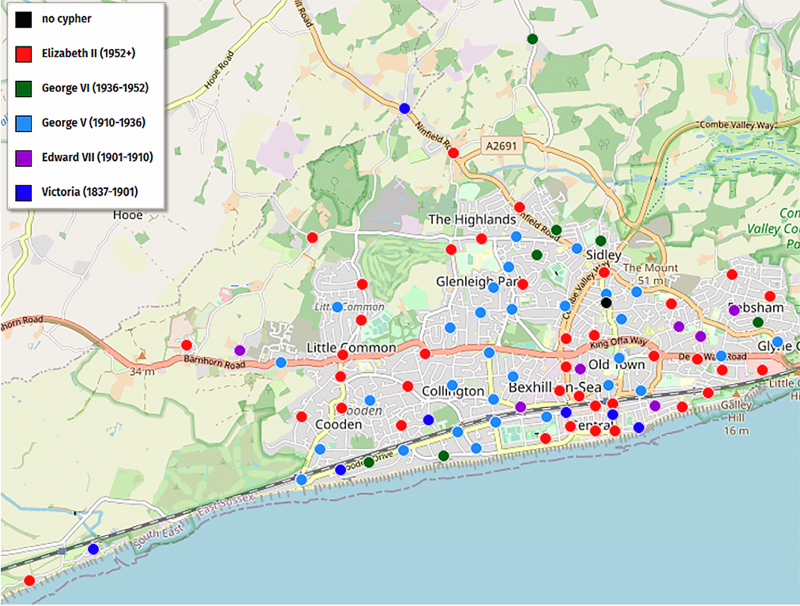

It is fortunate that the town benefits from the careful cultivation of its many other historic architectural features through the activities of a local society, Bexhill Heritage, whose motto is “Conservation, Protection and Improvement; caring for the past, present and future.” Among its several notable projects has been a cataloguing of all the 88 letter boxes in the town (or 90 if you count one located inside a hospital and another one in an adjacent suburb which is served from the Bexhill post office. These were mapped (below) and photographed by Paul Wright and Alex Markwick of Bexhill Heritage who generously made their archives available to me for this article.

This map of letter boxes illustrates the pattern of growth from the core area where the oldest boxes are still extant and the Queen Victoria cypher is recognizable with later cypher-marked boxes extending parallel to the seafront northward, westward and further inland. The oldest boxes are marked in dark blue (Victorian), after the Queen who ascended the throne in 1837. These have been supplemented by the more recent ones in red under the long reign of the current Queen, Elizabeth II. This was made necessary to keep up with the demand of population growth and limit walking distance between home and letter box to a maximum 10 minutes in the center of town. See map above denoting type of letter box by cypher and year of installation.

This map of letter boxes illustrates the pattern of growth from the core area where the oldest boxes are still extant and the Queen Victoria cypher is recognizable with later cypher-marked boxes extending parallel to the seafront northward, westward and further inland. The oldest boxes are marked in dark blue (Victorian), after the Queen who ascended the throne in 1837. These have been supplemented by the more recent ones in red under the long reign of the current Queen, Elizabeth II. This was made necessary to keep up with the demand of population growth and limit walking distance between home and letter box to a maximum 10 minutes in the center of town. See map above denoting type of letter box by cypher and year of installation.

Time Cards (below, L) on each letter box show when the letters are collected and the boxes are emptied and sent to the local post office for further sorting and onward delivery. This is the wall type variant rather than the free standing older “pillar” type below which bears the cypher of Queen Victoria (below, R). The newer wall type in the photo is from the late 1940s or early 1950s with the symbol of King George VI (the current Queen’s father) and is located in the center of Bexhill—one of the many boxes that had to be added to accommodate the growing demand over time and ensure that the boxes did not become too full due to overuse. Few new ones are built today due to the massive decline of writing letters requiring the help of the post office when home computers instantly deliver e-mail.

This letterbox in Dorset is the oldest in all of Britain at 168 years old.

This letterbox in Dorset is the oldest in all of Britain at 168 years old.

The Historical Development of the Letter Boxes

In 1840, Uniform Penny Post was launched, radically changing the way the postal system was used by the public putting increasing demands on it. As a result, the earlier systems for collecting, sorting and delivering letters had to change. One such change was in the means of people posting letters. Prior to the introduction of letter boxes, there were principally two ways of posting a letter. Senders would either have to take the letter in person to a “Receiving House” (an early Post Office) or would have to await the arrival of the “Bellman.” The Bellman (R) wore a uniform and walked the streets collecting letters from the public, ringing a bell to attract attention.

In 1840, Uniform Penny Post was launched, radically changing the way the postal system was used by the public putting increasing demands on it. As a result, the earlier systems for collecting, sorting and delivering letters had to change. One such change was in the means of people posting letters. Prior to the introduction of letter boxes, there were principally two ways of posting a letter. Senders would either have to take the letter in person to a “Receiving House” (an early Post Office) or would have to await the arrival of the “Bellman.” The Bellman (R) wore a uniform and walked the streets collecting letters from the public, ringing a bell to attract attention.

Early Trial Start in the Channel Islands

The Post Office first encouraged people to deliver mail to the local post office. In 1840, the idea of roadside letter boxes for Britain was suggested. Letter boxes of this kind were already being used in France, Belgium and Germany. However, there were no roadside letter boxes in the British Isles until 1852, when the first pillar boxes were erected at St. Helier on the Channel Island of Jersey at the suggestion of Anthony Trollope, a noted author, who was working as a Surveyor’s Clerk for the Post Office.

A trial was instituted on the offshore Channel Islands to test the idea and was successful so that by 1853 they started to appear on the British mainland. During this initial period, different manufacturers were utilized and the result was a variety of different styles, sizes and colors. In basic form, all boxes were vertical ‘pillars’ with a small slit to receive letters. A long trial and error period ensued and by 1857 horizontal, rather than vertical, apertures were accepted as the standard. Flaps were put over the apertures to prevent rain finding its way inside and the position of apertures lowered to below a slightly protruding cap. As developments progressed, additional lessons were learnt about the most effective type of boxes.

The Post Office realized that having so many different designs of letter boxes across the country was proving confusing and expensive. Instructions were issued to introduce a new standard box. It was to be available in two sizes, a larger, wider size for higher volume areas and a smaller narrower version for elsewhere. It took its lesson from the early experiments and was cylindrical with a horizontal aperture and a hood to help keep out the rain.

Penfold’s Standard Letter Box

In 1866, the Post Office again produced a standard letter box designed by J W Penfold which came in three sizes. Problems were encountered with some of the early designs however, and modifications were made, such as the inclusion of downward-pointing slides to help prevent letters being stuck. Green was first required as the standard color but complaints mounted from the public that they were difficult to spot and by 1874, a more visible bright red was specified. It took 10 years to complete the program of re-painting but it remained the standard color from then on.

In 1879, a further standard box was produced. This time, more of the earlier lessons were taken on board. The new standard box at last resembled the letter box that is today the iconic image of Britain—cylindrical with round cap and horizontal aperture under a protruding cap with front opening door and black painted base. This 1879 style box proved to be the most effective in design. In the 1930s, special boxes were introduced for posting airmail letters, these were painted blue.

From 1939, blue airmail boxes were removed, repainted red and re-entered service for standard mail. Ironically, although the Channel Island of Jersey was the birthplace of the distinctive red box, the nearby island of Guernsey painted its boxes a distinctive Oxford blue to highlight the Guernsey Post Office’s new branding and image. The single exception is Pillar Box number 1 in Union Street, which has retained its original burgundy-red color and is the oldest working post box in the British Isles.

Contrasts with the American System

Americans who have settled in the U.K. eventually notice that, unlike the United States, British postal service does NOT include the pick-up of mail from private residences located in rural areas. In these U.S. locations, home owners must place their own privately owned letter box near the entrance to the home if they wish outgoing mail to be picked up by carriers for delivery to its destination. The mail carrier checks to ensure that the letter or parcel is within weight limits and has properly paid affixed postage stamps. Nothing else may be placed inside the box by anyone except the letter carrier who will deliver arriving mail in the same box.

American mailbox in front of private home waiting for collection of outbound mail denoted by the upright flag.

American mailbox in front of private home waiting for collection of outbound mail denoted by the upright flag.

The “flag” pointing downward means there is no mail to be picked-up. An upright flag indicates there is a letter to be picked up by a carrier when he stops to deliver incoming mail to the recipient on his route. Most people in urban areas who live in apartment buildings and condominiums have a central delivery box in the lobby on the ground floor and access by elevator. They can simply drop their outward going mail in the chute without having to go downstairs to the lobby. They will also have a private box in the lobby for incoming mail to be delivered by the carrier (see below).

.jpg)

Outdoor American mail boxes lack the historical character of the red British letter boxes. They are also generally located much further away from one’s residence compared to the much smaller mailboxes attached to lamp posts that I recall from my teenage years, but which are also fast disappearing. The photo above right reminds me of my local neighborhood box across the street from where I lived in the Bronx.

Having travelled and walked about throughout many British towns as a sight-seeing pedestrian, I can also testify to the fact that the street letter boxes serve more than the purpose of expediting the mail at a stage in delivery. They are an important element in the visible townscape and serve as an aid to finding one’s way. Here is a pillar letter box in front of shops amid very similar house types on Sackville Road, a High Street, in Bexhill.

Bexhill town hall and its letterbox

Bexhill town hall and its letterbox

Amid the hustle and bustle of a crowded street in a new location and many similar looking buildings and shopfronts, the sight of a letter box is a help in gaining familiarity with the immediate surroundings.

A busy day along a high street, the bright red letter box provides a recognizable landmark

A busy day along a high street, the bright red letter box provides a recognizable landmark

Britain and America still differ in many ways that come to mind immediately, the direction of travel, Centigrade vs. Fahrenheit, Monarchy vs. Republic, Electoral systems. Another one that is apparent after more than a very brief stay is the contrasting postal systems and their visual imprint on the landscape.

______________________

Norman Berdichevsky is a Contributing Editor to New English Review and is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast