Call it What it is: A Lit-Crit Exercise

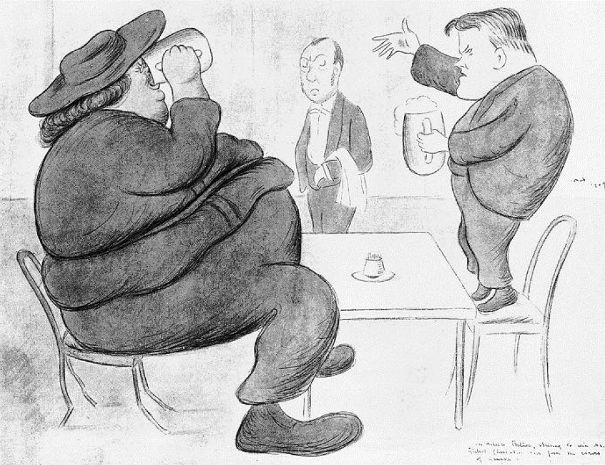

Belloc lecturing Chesterton about “the errors of Geneva,” Max Beerbohm, 1907

The most learned book in the humanities I have read in recent memory is John Gross’s The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters, first published in 1969. Gross, who died in 2011, was not a full-time academic (taking appointments only occasionally) but instead a literary journalist, anthologist, critic, literary historian, and memoirist; but he knew more about English Literary Life Since 1800 (the subtitle) than any English Professor, I am fairly certain. You can tell he knows the major poets, novelists, and dramatists of those 160-odd years, but he knows a phenomenal muchness about the “Men of Letters,” famous and obscure as well (“obscure” at least to me). I‘ve read Thomas Carlyle and such: I have only heard of A.R. Orage and such; I know who Leslie Stephen was because I’ve read his daughter Virginia Woolf; and so on.

I also know (I can’t mention everybody Gross analyzes) besides Carlyle, Mathew Arnold for instance, G.K. Chesterton, George Orwell, and T.S. Eliot. . . to keep things familiar and within range. I also know of Francis Jeffrey because unlike the obtuse critics and reviewers of the time he praised John Keats. I greatly admire the Victorian Walter Bagehot, although his literary criticism means less to me than his political thought as in Physics and Politics. I know and dislike the criticism of F.R. Leavis, especially The Great Tradition where he can find no place for Charles Dickens as novelist. But now I’m about to say something which contradicts the so far positive tone: for all the brilliance of Gross’s analyses of this figure and that, this is an annoying book.

In an intellectual history of “English Literary Life Since 1800,” why these figures and not some prominent others? What do Carlyle, Arnold, Chesterton, Orwell, and T.S. Eliot have in common? Orwell was a novelist who wrote criticism; Carlyle was a critic and historian who wrote a novel (his odd book Sartor Resartus); Chesterton was a critic who wrote poetry and fiction; Eliot and Arnold were poets who wrote criticism. Jeffrey, Bagehot, and Leavis were critics who were not artists. But if they were all “men of letters,” why is Keats, who is merely mentioned in connection with Jeffrey, not a man of letters as well as poet? The meaning of Man of Letters is a muddle, and Gross does not clarify things. In general the definition is either too broad or too narrow. For some people it means a scholar of literature and/or a writer, which indicates hopeless numbers of men and women characterized by nothing but an ability to put things down on paper. For Gross it means essentially a critic and/or a reviewer. But why is Jeffrey a Man of Letters, commenting on literature, and Keats not a Man of Letters, merely creating literature? The actual Men of Letters analyzed in Gross’s book are Carlyle, Arnold, Chesterton, Orwell, and Eliot.

Thomas Carlyle was (although not regularly noted as such) an unorthodox writer of fiction, a critic, an historian, and intellectual essayist. Mathew Arnold was a poet, essayist, and critic. G.K. Chesterton was a critic, religious and political thinker, poet, and novelist. George Orwell was a novelist, critic, familiar essayist and memoirist. T.S. Eliot was a poet, critic, and philosopher. In other words, all were artists who wrote notably in other genres as well. John Keats was a poet, who wrote in no other genre, unless one wishes to consider the personal letter a genre.

Elsewhere I have mentioned other Men of Letters—not all English however. Randall Jarrell was a poet of course, but also a novelist and critic extraordinaire. Edmund Wilson was the best critic of the 20th century, an intellectual historian, who also wrote fiction, drama, and poetry. The poet Allen Tate, was also the critic Allen Tate, and novelist and biographer. The philosopher George Santayana also wrote poetry, criticism, memoir, and a novel. Historian Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote criticism and poetry as well. And George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans) was a Man (Woman) of Letters: novelist, poet, critic, translator, and occasional philosopher.

These—along with Carlyle, Arnold, Chesterton, Orwell, and T.S. Eliot—are “descendants,” so to speak, of Dr. Samuel Johnson, poet, critic, novelist, biographer, lexicographer. . . that is to say Man of Letters. No other designation does him full credit. What should we call John Milton, author of Areopagitica as well as Paradise Lost, etc.? You know my answer. Same with Samuel Taylor Coleridge with his Biographia Literaria and Kantian philosophizing. And then there is Thomas Mann und so weiter. One could go on for pages. So this is a grand tradition, to which most of Gross’s subjects, most of them only critics and book reviewers, do not belong.

This does not make me particularly happy. I write and publish constantly: criticism, philosophy, intellectual and cultural history, political commentary, memoir—so I seem not to (and do not) have an exclusive specialty. I’m best called, I suppose, an essayist. I would dearly like to think of myself as Man of Letters. But … I have never tried my hand, sober, at poetry, never at drama. I wrote a short story when in high school, which I recovered among my mother’s papers after her death, apologized to her memory, blessed woman, and managed to misplace it. About 40 years ago I tried to start a philosophical mystery novel, got one chapter done, read it, and managed to misplace it quite intentionally.

I mentioned just above that I am not a poet—and never seriously, soberly, tried to be. I am told, however, by a few kind people that my prose is often rather poetic, which of course pleases me—pleases me, however, that I have a few kind friends. But I have a sky-high notion of what poetry is that will not allow me to be fooled by kindness. If I really believed that my prose was poetic instead of just rather good, I might be tempted to call my shorter pieces “prose poems,” and thereby join a fraudulent quasi-tradition. I don’t want to call anything fraudulent “traditional” since tradition is practically a holy word for me; if the fraud is constant and long-term, let’s call it “sustained semi-convincing nonsense.” I, who think there’s a stark difference between critic and man of letters, insist on clarity of designation and definition.

Let us not be misled by the old French term which has become native English, “belles lettres.” It means of course “beautiful writing” or perhaps “fine writing.” But neither beautiful nor fine necessarily means poetic. Dictionaries will tell you that belles lettres refers to writing enjoyed for itself as much as or even more than for its meaning and content; but it is possible to enjoy for itself, given a breadth of taste and given an author’s intention, writing which is brutal, harsh, and goddamned mother-humpingly awkward—since the eye of some beholder sees beauty there, or rather the ear hears.

In my view, looking at and hearing a piece of writing and calling it a prose poem is rather like looking at a man and saying “That’s a very tall short guy; he must be at least 5’2”—which might make you sound like a clever dude with a unique vision, but says nothing about the guy observed himself. The French poet Saint-John Perse could call this piece or that a prose poem, but it was merely an aesthetically idiosyncratic piece of verse or a piece of prose not wished by its creator to be identified as such; and its creator himself was joining a fraudulent quasi-tradition. But the problem is that lesser dudes than Perse can write a prosaic screed with no musicality to it at all, such that no reader-hearer could identify the work as a poem, and the creator-dude can protest, “But it’s a prose poem!” So, in my view again, a “prose poem” is just a piece of prose, which doesn’t make it bad prose, it may be quite good, but bad poetry. Want an analogy? A supposedly philosophical essay which is all feeling and assertion may be quite entertaining I suppose, but it is bad philosophy to the point that it’s not philosophical at all: because it’s without the process of rational thought that philosophy requires, just as Platonic dialogues can be quite entertaining, but it’s intellectual entertainment that Socrates offers. Open the analogy? The “prose poem” is without the specifically aesthetic virtues that make poetry poetry.

One should not assume that I think all poetry must rhyme, must have metrical regularity, be imagistic, metaphorical, deal in similes, paradoxes, etcetera, etceterum, etceterhumba. Not that I am going to define what poetry is—if one doesn’t know already, that is to say can’t hear it, there is no way of grasping a definition anyway. I’m not attempting to cop out; I am hoping the reader is old enough to remember what poetry sounded like in the days before the invasion of prose into the realm of poetry, the sound that hooked him or her when a kid, assuming hookdom. But I will confess a private prejudice, so to say; whatever the use of those tactics from rhyme to etceterhumba, poetry in English at any rate to be the true thing, must at the very least remind my ear—I’ve said this more than once and now written it twice—“of the profound and noble rhythms of the King James. Otherwise, merely workaday prose.”

Possibly except for the reference to the King James above, I cannot believe I am alone in this. And by “this” I do not mean only my dismissal of the prose poem. I mean what the prose poem signals: the pop notion that poetry need not be traditionally poetic to be real poetry, that dozens and dozens of people ostensibly poets like the prose-invasion because they are without the talent to write otherwise. I have more or less ceased attending “poetry readings.” But there were two I wish I could relive.

Perhaps 10 years ago in the Westport (CT) Country Playhouse, Christopher Plummer gave a reading of old favorites and some new. I am always attentive to audiences, and this was not the audience I’m used to at colleges or hip locations in Manhattan. Yes, they were educated and middle class, but were probably there to see and hear a movie star rather than out of hunger for poetry. But perhaps latent hunger was aroused, and voracious. For almost two hours Plummer with no props simply recited from memory or aided by text said expressively poem after poem to rapturous applause sometimes and sometimes to stunned silence before eventual eruption. When the reading was over the audience clearly did not wish to leave: it was the slowest exit of people in conversation I have ever seen in a theatre. This experience became a sort of touchstone for my wife and me: whenever she bemoans the state and place of poetry in our culture, one of us is liable to say “But remember the Plummer reading”—meaning both the reading and the audience. A couple of years later Sam Waterston gave a reading at the Congregational Church in Cornwall, Connecticut: similar audience, essentially the same reaction.

Yet literary agents will tell you—and mainline publishers will agree—that poetry will not sell unless it has some meta-literary attraction: perhaps a popular political bias, maybe identity politics; or maybe the author (let’s not say the poet) is a non-Caucasian, one-armed, transsexual, Muslim ex-con. That the experimentalist yet traditionalist (that is to say real) poet Dana Gioia sells quite well never seems to make the news in the literary agency or the mainline house. Or maybe they are not literate enough to know what real poetry is … which I think is indeed the case.

It is indeed the case in those publishing houses that specialize in poetry, where one should expect literacy. But … whether one—not the transsexual ex-con imagined above—publishes his or her stuff in a journal like NER, where the level is respectably high, or aesthetically embarrassing as in, surprisingly, The New Yorker, or in the once-great Poetry, which deserves my caricature as “once-great,” the poet finds it hard to have his or her stuff converted to book form (unless he or she is indeed a non-Caucasian, one-armed, bi-sexual, Muslim ex-con), for the way to book form is to win a contest (which by the way is profitable for the publishing firm since it charges a fee to each contestant). The publisher does not read the submissions to the contest—probably unequipped to do so—but proudly advertises that the judge of the contest will be the supposedly wonderful poet Whatsthename, who may have won the contest a few years before. Before the judge sees a manuscript, however, most MSS are eliminated by sub-editors, graduate students (oh yes!), and other ill-paid hangers-on, before the few reach the judge’s desk. The judge, however, will not be someone of the level (if that’s possible) of W.H. Auden, who famously was generous and as free of self-interest as a human can be and eager to find his equal or near-equal at least. But the typical contest judge (and I have read selections of several) is quite simply not looking for his superior! So, trusting logic as we must, we know exactly what he or she is looking for. If the reader thinks that I am possibly making guess-work assertions in the sentences above, I have a confession to make, I have some general “inside” information about the process—which of course I am not willing to divulge because I think it not ethical to break a trust. So the reader or anyone else may trust me or not: his or her choice.

In any case, here is my major point so far: just as not all literary critics are men or women of letters, not all versifiers, very few, I think, are poets. Indeed, the vast majority of poems published are actually, rather, prose poems. I am sure the reader takes my meaning. Our cultural language is just too loose. I know however that there’s not a hell of a lot we can do about it. Oh, perhaps Critic can be reserved for those who write criticism, while Man or Woman of Letters retains a higher distinction, and he who would like to possess the latter term, as I have confessed I wish I could, could accept “demotion” even if not required to by law. But there’s little chance that the Prose Poet, so to speak or so to utter, will accept the just designation of Poetaster.

And speaking of contests, as I was above, I have noticed that some literary publishers have added to the categories of genre such as Poetry, Drama, and Fiction (all good sources of fees) “Creative Non-Fiction.” What is that? Of course the word creative has various meanings which have little specifically to do with “creation”—as in “lively” and “imaginative” and so on. But in literary talk things get more specific. We call the person who writes poetry or fiction or drama a creative writer, meaning he or she makes up a poem or story or play instead transcribing literally what’s been seen to happen. But the word fiction means a story that’s been made up, while the phrase non-fiction generally means a story or report or observation of what’s been seen to happen—not precisely the same as essay (literally an “attempt”) meaning a transcribed process of thought.

Therefore, since in literary talk creative and fictional and made-up-ness (if you’ll excuse the awkwardly made up locution) are all related and to a degree interchangeable, “Creative Non-Fiction” logically means “A Fictional Piece of Non-Fictional Writing,” or “A Made-Up Piece of Observations Not Made-Up”—further and further into nonsense. Of course I know that’s not what the careless practitioners of Lit Talk mean; it’s only what their words mean—but the word only there is a measure of their carelessness. They mean to say that some non-fictional writing is lively and imaginative. But what writing good enough to be published should not be lively and imaginative, since the opposite of that is dull and awkward? (As much of the Creative Non-Fiction that I’ve read is.) Let’s get serious. (Which sometimes can mean “Let’s get ironic.”)

One kind of non-fictional writing, done by the non-creative writer, is Philosophy. I know. And the philosophical essay should be lively and imaginative, not dull and awkward (as too much academic philosophy is). But, hold on, the philosophical essay (including of course political theory) should be also creative in the Lit Talk sense. Unless it is only an exposition or summary of someone else’s thought, the ideas should belong to the essayist, so in a sense are “made up” by him or her. O.K, enough irony. But the same goes for the sociological and the psychological essay as both disciplines are academic breakaways from classical philosophy.

The most popular and populace Non-Fictional writing is, by far I think, History. Which of course should always be telling, or seeking, the Truth of What Happened: otherwise, Stalinist-style partisan propaganda, that is to say Lie. Of course there’s the sub-genre Historical Fiction, but I’ve had my say about that before (“Taking the Historical Novel Seriously,” NER, September 2018), and often the historical novelist makes discoveries the historian was not aware of, especially when the protagonist is not a fictional character but an historical figure, Lincoln, Grant, Lee or whoever. And to complicate or “ironify” matters, the historian occasionally finds he or she must resort to making-things–up. Naturally I do not mean inventing a person, a hurricane, a depression, a war, or any somesuch. But imagine the following.

The historian knows that event A happened shortly before B event, but is not sure—clear evidence is just not there—of a causal relationship between the two, although that would make a sensible connection. So the historian might make up “The causal connection is too believable to be dismissed: yes, B occurred because A did.” But the historian might on occasion be more inventive than this. Imagine there is an event I’ll call X, which would not have been possible without conditions set by earlier events. So X was possible, but possibility and probability are quite different matters, and X was not very probable, indeed was a total surprise, and makes little sense, unless. . . . Unless there had been some event historians know nothing of, not even its possible existence, which might have, possibly, increased the probability of X—so we invent event Q which answers the question of how X came about, to which we add “must have.” Without the chance of being occasionally creative in the Lit Talk manner History is going to be an even more inconclusive discipline than it already inescapably is, so far from knowing What Really Happened that historians might as well accept unemployment. None of this means that History is Creative Non-Fiction any more than Philosophy is.

The writer who would call him- or herself Creative Non-Fiction Writer (actually I’ve never heard any actual person claim the title) would be like the Critic who would claim to be a Man or Woman of Letters: an exaggeration of status or “promotion,” so to speak. No one calls oneself Prose Poet that I know of, but the author of what he or she calls a Prose Poem should cut it out and call it a paragraph, although I don’t expect to hear Poetaster admitted. They might all take a lesson from me. Man of Letters I wish I could promote myself to, but am modest enough to call myself Essayist, which ought to be good enough since that’s what William Hazlitt, the greatest English non-fiction literary writer, was (which adjective gives him the advantage over Winston Churchill). I’ll settle for that tradition.

Since these reflections began as thoughts on John Gross’s magnum opus, I should add that that’s his tradition as well, within which he is closer in quality to Hazlitt than I will ever be. By the way—or more than that—I am about to re-read favorite chapters of his memoir, A Double Thread: Jewish intellectual, English essayist. And I have just ordered his Shylock: Four Hundred Years in the Life of a Legend.

***

After this essay was completed I finally read Gross’s Shylock, and I must revise my first sentence: The most learned book I have read in recent memory is Shylock: Four Hundred Years in the Life of a Legend. After his own analysis of The Merchant of Venice with of course special emphasis on Shylock, Gross surveys four centuries of same in England, the United States, Germany, France, as well as quick sketches in Russia, China, Japan, and a vast etcetera, which includes Yiddish, Hebrew and (pause) Nazi productions. He examines possible sources which inspired Shakespeare, as well as works which could have been inspired by Merchant, as well as depictions of Jews in literature whether or not directly related to Shylock. All this amazingly in less than 400 pages. I should mention as well a feast of allusions. How many people know the real name of the comic genius Jack Benny? Benjamin Kubelsky. Can you imagine why Benny would be mentioned? No? Then read the book.

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others. His new book is Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Kenneth Francis)

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast