Catching a Cloud

by Theodore Dalrymple (December 2023)

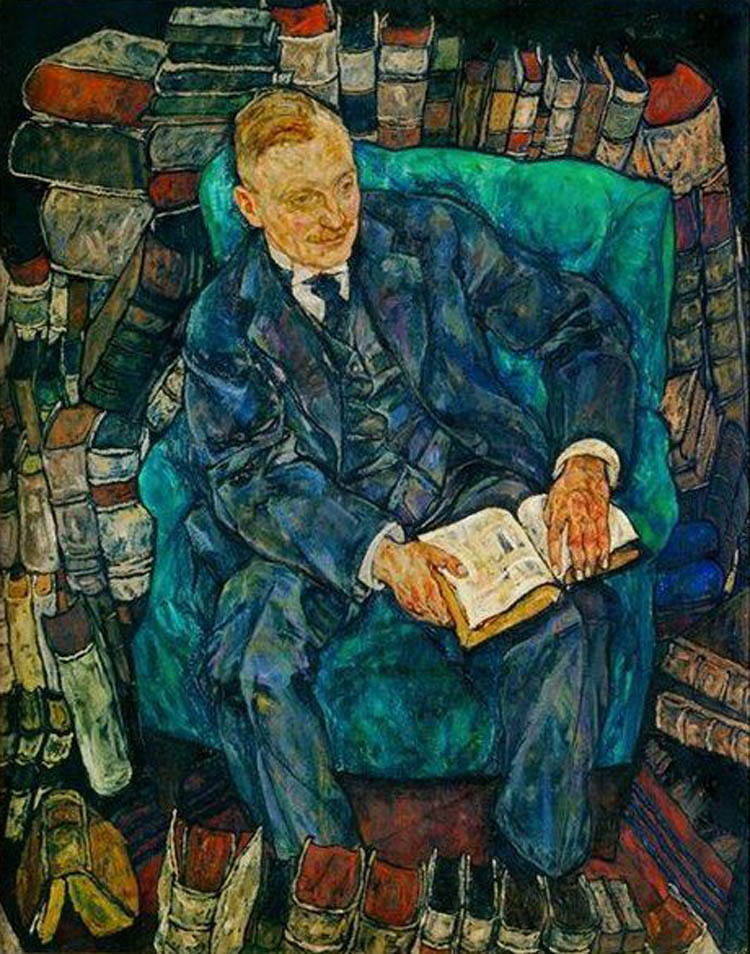

I am a great admirer of Joseph Epstein, the literary critic and writer of short stories. He is erudite without pedantry, genial without condescension, and clear without superficiality. He does not argue with the tiresome intellectual orthodoxies of our time, he simply ignores them as too boring to notice—and he is right.

He leaves to others the task of grappling with the rebarbative ideological prose of modern literary academe. Not for him titles such as Anthony Trollope and the Masculine Abject or P.G. Wodehouse, Subaltern of Empire and the Legacy of the Slave Trade. He does what a good critic should do: he conveys his enthusiasm for literature. He helps us to see what we might otherwise have missed and he helps us to ground our judgments without insisting that they precisely coincide with his. His views are firm but not dogmatic, and his values are literary.

Criticism such as his, enjoyable by any normally literate person, used to be the norm, but now it takes courage (or a private income) to ignore the sneers and hoots, the denunciations and the menaces, of the Mesdames Defarge who would sit knitting at the base of the academic scaffold, and still to write. One should be careful not to exaggerate or draw false historical comparisons, but Joseph Epstein seems to me to be like a man who has gone into inner emigration, as some German intellectuals once did, in his case from the republic (or oligarchy) of letters.

He has now written a short but bracing little book, The Novel, Who Needs It? The title, I suppose, may be thought to be symptomatic of a certain anxiety. Mr Epstein, now 86, has spent his life reading, and now finds himself at the end of a long career living in a culture that devalues that activity, at least in his sense of the term. Glancing at predigested short passages on a screen does not count for him as reading; but it is the most that many young people now can, or at any rate are prepared, to do.

There is no denying the loss of cultural salience of the book in our world. The evidence is everywhere. When I travel on the Paris Metro, for example, I look around me to see who is reading a book: to which the answer is, usually, no one. By contrast, it is not unusual—in fact it is usual—to be surrounded by ten or even twenty people all to a man or woman glued ocularly to their telephone screens.

In theory, of course, they could be reading books on their apparatus, even War and Peace; but in practice they are not. They are (if my unscientific survey is to be credited) looking at clothes catalogues, clips of violent movies, or videos of themselves and others during a recent riotous party. It is to me very depressing, but in the back of my mind there is always Somerset Maugham’s question in the story, The Book-Bag: from the standard of what eternity is it better to have read a thousand books than to have ploughed a thousand furrows? Great readers are apt to suppose that they are not merely amusing, but improving themselves by reading; and not merely that, but improving the world also.

At any rate, to have been a great reader all one’s life and to end it in a culture in which reading has become unimportant, one feels a little as I suppose aged horse-drawn carriage-makers or ostlers must have felt as the motor car superseded the horse: that one has, in some sense, wasted one’s life.

The novel is only a branch of the great tree of reading, and perhaps one that is particularly vulnerable to adverse criticism in a world in which children must be hurried from an early age from activity to activity, with never a moment left to then to amuse themselves, and in which a moment vacant or wasted is thought by parents to be deleterious to future chances of a career.

Mr Epstein is spirited in his defence of the novel as a genre. It is the novel’s capacity, at its best, to illustrate the complexity of life that is its glory, for no other literary or artistic genre can do so. The novel is a kind of vaccine against the terribles simplificateurs who are the bane, or at least a bane, of this world, the kind of people who think that they have found the key to life as Mrs Baker Eddy thought that she had found the key to the Scriptures, or Baconians think that they have found the key to Shakespeare.

Of course, novels—but not good ones—can be used to further ideological purposes. An obvious example is that of Ayn Rand and her doorstop pamphlet-novels, which are about as amusing as a sermon by the Ayatollah Khomeini. The only good novel in straightforward pursuance of a case that I know is Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s Dr Therne, a clever little pro-vaccination (against smallpox) novel that he wrote in the face of that anti-vaccination movement, by far the longest-lasting social movement in Britain in the second half of the nineteenth and first part of the twentieth centuries. But even so, no one would claim this fictionalised tract as one of the chief glories of English, let alone world, literature. If you want straightforward suggestions about what to do, you are better off with company prospectuses than with novels.

It is a curious feature of novels that their characters may become more real to us than some, perhaps most, of the people around us. Mr and Mrs Micawber, for example, are far more present in my mind than my next-door neighbours (on one side), who remain the most shadowy figures to me. What makes my neighbours tick—if they do tick? I haven’t the faintest idea, whereas I feel I know Wilkins Micawber intimately. I was very pleased, incidentally, that Mr Epstein referred to Mr Micawber’s dictum as the greatest summary of economic wisdom ever written, by far:

Annual income 20 pounds, annual expenditure 19 pounds 19 [shillings] and six [pence], result happiness. Annual income 20 pounds, annual expenditure 20 pounds ought and six, result misery.

For many, the reading of novels is a waste of time. Like Mr Epstein, I retain only a tiny proportion of what I have read in them, a line or two perhaps, or an atmosphere. Does that mean that my time has been lost or wasted?

This in turn raises the question of what I would have been doing instead, had I not ben reading novels: and the memory of how much of that, whatever it was, would I have retained? How much of the time I have spent cooking or taking walks is now completely lost to me, but no one says that cooking or talking walks is a waste of time. Except for those rare (and unfortunate) people who forget nothing, about one of whom the great Russian psychologist A.R. Luria wrote a famous book, we all forget a vast proportion of our own experience: which is as well, for a mind cluttered with everything would find it impossible to concentrate on the significant.

This is not to say that the faculty of forgetting is always judicious, of course. Recently, I was going through my old notebooks, practically all of them undated, and was alarmed to discover that much of what I would like to have remembered, and really ought to have remembered, has disappeared for good from the engrams in my brain. For example, many of the notebooks were of my visits to the republics of the former Soviet Union shortly after its dissolution. I visited prisons and hospitals, and spoke to many people who had been cruelly mistreated or tortured, but whose faces, voices, manner of being, are now completely lost to me, though they surely must have seemed unforgettable to me at the time.

But, as with a novel, and overall impression remains: of darks places, of dripping walls, of overheated wards void of medical activity, of people showing me their scars. It was not a complete waste of time, even if I did not make as much of it as I should have done.

Trying to describe or explain the whole of human life by means of principles, either moral or scientific, is like trying to catch a cloud with a butterfly net. It is here, according to Mr Epstein, that the novel reveals its incomparable strength, at least when practised by a master. To adapt slightly the end of Howard’s End, the novel is the attempt, never entirely successful, but nevertheless eternally necessary (insofar as human life is eternal), only to connect, that is to say, to understand the ground of our human existence. Mr Epstein writes:

What truly moves human beings? What is the force behind our Actions good and bad, behind hatred, love, loyalty, betrayal?

And he answers that ‘The novel has worked at answers to these questions more persistently than any other artistic form or intellectual endeavour. However circumstances and conditions may change, the great questions surrounding human nature do not.’

If the answers cannot be found, it might be asked, what is the point even of asking them? The logical positivists would have said that of there were no possible answer to a question, it was not really a question at all, but let us not detain ourselves by that foolish philosophy. The point surely is that questions about human existence cannot not be asked, even if many people do so only implicitly. It is the same with metaphysics: everyone at every moment has a metaphysical position, even if he does not know that he has, even if it changes from one moment to the next, even if he cannot enunciate it by means of conscious propositions.

In a very illuminating passage, Mr Epstein tells us how the critic Maryanne Wolf changed her attitude to Mr Casaubon, the dryasdust scholar in Middlemarch, George Eliot’s greatest novel. ‘I never thought I would see the day,’ she wrote, ‘when I empathized with Mr Casaubon, but now, with no small humility, I do.’ In other words, there is a dialectical relationship between the reader and the characters in a novel that is a genuinely educative process.

This raises a very difficult question, to which I do not know the answer: if novels educate our sensibility (as well as entertain), are we the better people for reading them? As a doctor, I am sufficiently wedded to the notion of empirical evidence that I desire some kind of statistical evidence that readers of novels are morally better than non-readers, but such evidence would be difficult, or even impossible, to come by: for one would have to control the readers and non-readers for all sorts of other variables. It is very unlikely that two groups of people could be found whose only relevant difference was in their propensity to read novels. Is there a dose-response relationship between reading novels and being a good person? And this also presumes that the concept of a morally-better person can be unequivocally defined, which is doubtful.

All I can say is that if one imagined a world without novels, and in which there were no possibility of there being any novels, it would be an impoverished world by comparison with the one we have. But this is a very weak conclusion. Mr Epstein’s is much stronger, to the question that the title poses, he answers straightforwardly, ‘We all need it,’ adding that ‘in this, the great age of distraction, we may just need it more than every before.’ The novel will cure us of our shallowness and make us aware of the tragic dimension of life, the lack of awareness making tragedy all the more unbearable when it strikes—as it does and always will.

There are many pleasures in Mr Epstein’s short book. I particularly enjoyed his account of the circumstances of the lifting of the ban in England on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, that ‘extremely dull and portentously silly and pretentious book.’ One day, I intend to write an essay on the way in which famous literary figures of the day perjured themselves in the witness box during the trial, letting the end they desired get in the way of telling the truth. This, of course, was the end of probity in public life. From now on, the end always justified the means.

Table of Contents

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast