Cedric

by Armando Simón (August 2021)

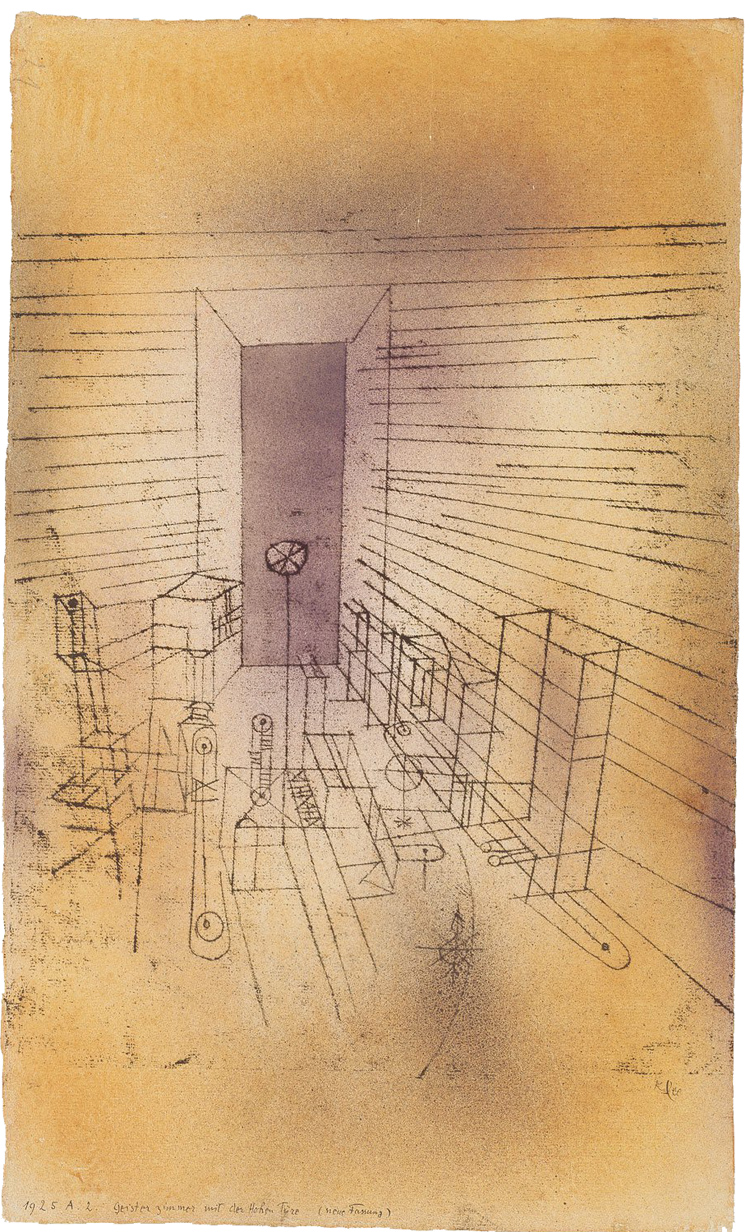

Ghost Chamber With the Tall Door (New Version), Paul Klee, 1925

The telephone rang at work. “Hello?”

“Hello, Mister Chapman?”

“Yes?”

“This is Nelson Mandela High School. We’re calling about your son, Cedric.”

Uh-oh. “Yes? What about him? Is he OK? Is he all right?”

“Oh, yes, sir! But there was a bit of trouble in one of his classes and the principal wondered if you could see him. He’d like to meet with you. Would it be possible for you to come down later on this afternoon, if it’s not too much trouble?”

“Well . . . how about now? I can take off and be there in half an hour or so.”

“Great. I’ll let the principal know. Goodbye.”

Cedric Chapman, Sr. had no problems in leaving work early. His boss knew that he was a widower, a single parent and, more importantly, there were no pressing issues at the moment at work.

So, he arrived at the school in the predicted time. Once again, he snorted with contempt at seeing the school’s new name; its previous one had been George Washington High School, but some people (three, exactly, strategically placed in positions of power) had decreed that the name of The Father of Our Country was too “divisive.” Nelson Mandela’s name, they said, was not “divisive,” but “inclusive.” No one asked the parents, the students, or the teachers whether Washington’s name might itself be deemed “divisive.” Or, for that matter, whether Mandela’s name was “divisive.” And Mandela was an African, not an American.

Although Chapman was naturally curious as to what the problem was involving his son, he knew at the same time that it was not serious, since the caller had indicated so, and since Cedric was very intelligent, very athletic, and universally liked by other students. The old stereotype that if you were athletic you had to be stupid, insensitive and bullying, or, conversely, that if you were intelligent you were scrawny, timid and weak, was obsolete. But he did have one “flaw.” If it could be called that.

He entered the school. Along the walls were inspirational posters meant for the edification of students, staff, and parents—not to study hard, or tryout for sports, or lead a healthy, law-abiding life. Instead, they were progressive kitsch, with messages like “This school practices Inclusiveness, Diversity and Equity,” “Transgender bathrooms available!” “There is no room for hate in this school,” and the like. He sighed and went into the office.

“Good afternoon,” he greeted the receptionist. “My name’s Cedric Chapman. I’m here to see the principal regarding my son. Same name.”

“Ah, yes, Mr. Chapman. I’ll notify the principal. Cedric’s over there,” she pointed to his right. He had not seen his son sitting on one of the plastic chairs because the door to the office opened to the right.

My God, he thought to himself, he’s magnificent.

It was true. And it was not the first time that the father made the, admittedly subjective, proud observation. Cedric was truly impressive, with an extraordinarily handsome face, a superb physique and he was one of those individuals that you look at and you instantly like him and, furthermore, you just know that he must be intelligent. Which he was. So, it was not just natural paternal pride.

Except that now he had a look of slight disdain on his face that he was trying to tone down.

He went over and sat down with him. “OK, so what’s the score? What happened?” The two were a contrast, the father a redhead with fair skin next to his dusky brunette son with, not just blue, but ice-blue eyes, most of his looks coming from his Lebanese mother.

Before his son could explain, the friendly receptionist said, “Mr. Chapman, the principal will see you now. You and Cedric can go right in.” They did so.

The principal was a thin man in his early 40s. They shook hands and sat down. The father instantly pegged him as one of the new breed of “educators.” An inspirational poster encouraging “Cooperation, not Competition,” with pictures of children of assorted races, with syrupy-sweet smiles on their faces, confirmed his assessment.

“Mister Chapman, thank you for coming. I hope it did not inconvenience you too much at work.”

“Not at all. Now, what’s the problem with Cedric, or should I say, involving Cedric?”

“Third period English class, with Ms Shanana and they’ve been having . . . differences of opinion. She’s now teaching Ebonics and— “

“Ah, E-wha-what? Excuse me, what?”

“Ebonics.”

“What’s that?”

“It’s African-American dialect.”

“Why . . . teach that? Why does that have to be taught in school? I don’t understand.”

“We want to be Inclusive and Diverse in our curriculum.”

“Ms. Shanana was trying to tell us that talk by knuckle-dragging ghetto trash should be acceptable, and on a par with standard English,” Cedric explained. “A bunch of bull,” he added.

The principal winced. “Cedric needs to be more openminded,” he suggested in a diplomatic tone.

“Sir, around here, the minds are so open that there’s nothing inside,” the young man quipped.

There’s Cedric’s flaw, all right.

“Besides, I was being openminded. I simply asked her if we were going to use Ebonics in class, then could we then, from now on, call her a ho?”

Cedric, senior, gasped, immediately followed by an ear-shattering, explosive “Ha!” bursting out, followed by immediately covering his mouth with his hand, surprised at his own outburst. He experienced a rapid sequence of emotions, one after another: shock, hilarity, pride, pretend to be angry, all in the space of two seconds. The principal, however, looked pained. “I think that was totally inappropriate.”

“Well, I thought it was right in keeping with the lesson. But, it’s not just that. That class is a joke, a total waste of time. We haven’t been assigned any of the classics to read: no Dickens, no Hemingway, no Shakespeare, no Dostoyevsky, no Maupassant.”

“Cedric reads a lot at home,” the father interjected and felt awkward in offering an explanation. But his son was on a roll.

“Instead, we have to read works by mediocrities who happen to be minorities, Chicanos and blacks who complain that if they get jock itch it has to be the white man’s fault, that if they don’t make it in life, it’s not because of their own shortcomings, it’s because of white people holding them down, and that the American Dream is an illusion.”

“We teach Chicano and African-American literature because they have been marginalized,” the principal patiently explained.

“Well, they should stay marginalized! They’re crap! If she wants to teach works by Hispanics, fine, there’s a ton of good literature from Spain! Matute, Pío Baroja, Unamono, Gironella, Pérez Reverte. But, here, nobody’s heard from them, they’ve just heard of Don Quixote.”

“And don’t get me started on poetry! No Frost, no Whitman, no Longfellow, no Dickinson? Instead, we read free verse and prose poems.”

“Free verse and prose poems are legitimate forms of poetry,” the principal patiently defended. He found himself in the awkward role of being defensive, a reversal of the usual bad-student/understanding-principal scenario, and he did not like it. But he tried to be Understanding. And Tolerant.

“Well, Robert Frost said that writing free verse was like playing tennis without a net. I say that prose poems is like playing tennis without a net, a racket, a tennis ball, or a partner! They have no alliteration. They don’t scan. They don’t rhyme. How in the world are they poems? They’re for people who can’t write poetry, but have pretensions of being poets!”

The father nudged his son’s foot to indicate for him to settle down, which he did.

“It’s not just English class,” the principal said to the father, “it’s his overall attitude in school. In phys. ed, for example, they held a track meet and when trophies were handed out, in front of everyone, he slammed it into the metal trash can, loud enough to be heard.”

“You threw away a trophy? You didn’t tell me that!”

“I came in first and you know what my trophy read? ‘Participant!’ Everyone got one! Of course, I threw it away! What was the point of the track meet, anyway?”

“To have fun, obviously,” the principal replied.

“Now, wait, Cedric’s got a point here.”

“Mr. Chapman, we don’t promote competition in this school. We promote Cooperation. Cooperation leads to a healthier lifestyle. You see, if you have a winner, then you have losers and their feelings get hurt. This way, everybody’s equal.”

“You’re serious.”

“I like competition. I like to be the best,” the teenager volunteered.

“And that attitude is precisely your problem. Mr. Chapman, some of the teachers complain of his arrogance—and he’s not subtle about it, either, he makes no effort to constrain his arrogance. At his age, in particular, it is jarring.”

The youth was about to say something, but his foot got pressed down even harder by his father’s.

“I’ll talk to him about it at home. I mean about his attitude. Was there anything else?”

“No, just work on that attitude. I hope you’ll make him realize the benefit of Cooperation over competition and that it’s good for everyone to end up with the same results in the end.”

Cedric was once again prevented from another outburst by his father’s foot pressing down even harder on his own. The boy’s toes were beginning to hurt. The school bell rang, signifying the end of the school day.

“Well, thank you for coming down.”

“No problem.” They shook hands and father and son left the office.

Without turning his head as they walked ahead, “That was going nowhere fast,” he explained to his son through gritted teeth.

“They’re a bunch of playerhaters,” his son responded in the same vein.

They went to the parking lot and entered the car, but he did not turn on the ignition. They sat for a few seconds, not moving or talking. The father’s facial expression was fluid, one that the teenager recognized from past experience as signaling conflicting emotions within his father, trying to surface simultaneously.

“Jesus Christ, Cedric!” he finally blurted out. “‘Can we now call you a ho?’ Really? Seriously??”

“What, Dad? It was in keeping with the lesson on Ebonics! You can’t deny it!”

“Don’t give me that! It’s me you’re talking to! And what happened when you said that?”

“She walked out of the room mad. I guess she went to the principal.”

“What about the other students? What was their reaction?”

“Same as yours. After she went out, they came over to me for high fives. They kept saying, ‘You the man! You the man, Cedric! You the man!’”

Figures.

“Cheez,” his father muttered, trying hard not to laugh in approval. “Cedric, this is your last semester in high school. The principal’s right. Try to control your arrogance,” the father said while he drove the car out of the parking lot.

“It’s not arrogance, Dad, if you want to be accurate, it’s contempt. I can’t stand most of my teachers. You know what they are? I got a name for them: mediocrity pimps. They’re pimping mediocrity.”

Another brief burst of laughter escaped from his father. He continued to make his point, though. “Yes, but it wouldn’t kill you to show some respect. No sense in making enemies. Pick your fights.”

But you, yourself, have said respect has to be earned, Dad. Besides, I respect Mister Fromm, my science teacher. I really do. He’s not like the rest. I like him. He makes us work hard. He pushes us harder than anyone else in that school and he won’t put up with excuses.”

“All right, but you are arrogant. It’s one thing to be arrogant if you have power and a totally different thing if you have no power. I’ve told you before: pick your battles carefully. The reason that you can get away with so much is that I’ve got you classified as black and they’re afraid that you’ll use the race card. But still-”

“I can’t believe that anyone thinks I’m black! All I’ve got is a perpetual tan.”

“Hey, if a blonde, blue eye senator can call herself an American Indian, then yes, you can call yourself black. She got a job in a big law firm by pretending she was Indian. And with your grades and SAT score, you got a bunch of scholarships by using the race card. The whole thing’s a racket!”

“Oh, and did you know that they’re going to do with grades altogether next year?”

“What? Are they crazy? Why?” He calmed down. “Wait . . . let me guess, I know why: ‘cause everyone’s go to be equal, right? And the lazy and the retards shouldn’t have their feelings hurt by having objective proof that they’re lazy and retarded, right?”

“Bingo! I’m just glad that I’m graduating this year.”

“It’s the triumph of the lowest common denominator,” Cedric Sr. muttered. “A total lack of values. But, to get back to what I was saying, there’s no point in making enemies, unless it’s necessary.”

Cedric said nothing, though it was obvious that he disagreed. It was really unnerving how totally unafraid he was of his teachers. Fear of teachers is something that is ingrained in all students from an early age. Not Cedric, though. He was not even afraid of the principal, for crying out loud, he was ready to go toe to toe with him. It was unnatural. Unnerving.

Yet, it made him proud.

“Don’t forget, tomorrow we go to the university counselor for choosing your classes for the fall.”

“I didn’t forget,” he said, matter of fact. He was not angry at all with his father. He understood what he was trying to instill in him and, besides, he knew that deep down his father approved of what he had done. It was obvious.

The day’s unpleasantness was left outside their home and dinner and the evening were unremarkable.

Later, at night, Cedric told him that he was going out on a date.

“Fine. Have fun with Miss Celaneous.”

“Her name’s Sandra, Dad.”

“Whichever. You also going out tomorrow night?”

“Yeah. I’m going to the movies with Elena.”

“Like I said.” The youth was about to depart. “Oh, don’t forget about the symphony tickets for tomorrow afternoon.”

I know. What’s playing?”

“I think Berlioz, Brahms, maybe some Mozart. They’re having a guest conductor. That’s all I know.”

“You got free tickets from work, didn’t you?”

“Yeah, as a little compensation for the compulsory United Way ‘contributions.’ There were just a few tickets given out by the symphony, as thanks.”

“Well, gotta be going. Bye.”

“Bye.”

The next morning, a Saturday, saw them both at the university in a crowd of freshmen making the necessary preparations for their enrollment. It was organized chaos. Cedric had been accepted long ago and after an hour or so of paperwork went to his assigned counselor to discuss choice of classes. That done, they returned home.

Father and son went to the concert hall Sunday afternoon and sat down for the concert. The guest conductor was introduced as being superbly talented, “A New Voice in Classical Music,” at which point the guest conductor appeared. He was young, black, skinny, wearing not a traditional tuxedo, but a tiny pair of spandex mini-shorts and a tank top. As he walked across the stage, to the audience’s welcoming applause, his arms and body twisted at unlikely angles, back and forth. On reaching the podium, he gave a curtsy.

Cedric gave his father a look that said, Seriously? You brought me here on a Sunday afternoon for this? But his father did not notice him. He was staring, openmouthed, at the spectacle. He finally noticed his son, shrugged, and gave him a look that said, I had no idea.

The symphony started, a piece by Mozart.

It was a mediocre performance. Mangled.

Yet, when it ended, most everyone jumped to their feet in a loud, standing ovation. A few spectators, however, sat rigidly in their seats, scowling. A few others, confused, unsure of themselves, and believing that there was something that they had overlooked in the performance that merited a standing ovation, hesitantly stood up and joined the herd in applause.

Cedric leaned over to his father. “I’ve heard enough. Let’s blow this joint. Please!”

“Agreed,” he nodded and they left the concert hall. On the way home, the mood changed to hilarity as they ridiculed what they had witnessed and, now, in a way, they wished that they had not left the performance, though neither would have admitted it.

On Monday, at work, there were two announcements. One was a new hire for the mid-level position of Coordinator, a position that several of the employees had applied for. Someone outside the company was hired who was said to be eminently qualified, since he had a double major, one in Women’s Studies and the other in Fat Studies.

The second announcement was that the HR department would put on a workshop, Towards a More Equitable World by Ending Toxic Meritocrazy, staggered at different hours that day. Everyone was expected to attend and participate. No one explained what the hell a More Equitable World had to do with an insurance agency, but such indoctrination sessions had become a regular feature of the workplace, and not just in Cedric Sr’s company where he worked, but almost everywhere and were universally despised by everyone, except for the few enthusiasts. The sessions were simply seen as another of life’s irritations that one had to put up with. Yet, no one had ever objected, or refused.

Chapman attended on his time slot. The . . . “facilitator” was already there, a fat, black woman reminding him of a bloated bullfrog; at any moment her tongue might whip out and catch a passing fly.

She passed out the handouts. Her name was on the top, at the corner: Pajama Jones.

No way, it’s got to be a joke. Nonetheless, though smiling, he kept his mouth shut, as did all the other attendees, though his colleague sitting next to him pointed at the title and the name, and rolled his eyes.

The “facilitator” had a friendly demeanor employed to diminish resistance, or hostility, but the words and ideas that were coming out of her mouth were annoying to the point of irritation:

• Meritocracy was the idea that through hard work, talent and determination, one could succeed in life.

• Meritocracy was in reality a racist concept, designed to keep minorities and women subservient to white people, especially to white men. Women and minorities would never improve their lives; they could not; they would not be allowed to succeed by white men, who would tell them that their failures were because of their inherent deficiencies as minorities and women and for not working, or studying, hard enough. In reality, the “failures” were due to racism and sexism and capitalism.

• Meritocracy was an offshoot of capitalism and of “whiteness” —whatever that was, she did not bother to define it, though her tone of voice and facial expression indicated that it was a bad thing, very distasteful.

• Fortunately, universities were coming around to this enlightened idea. To enter colleges, first, there were racial quotas and, second, in SAT scores required for entering college, blacks and Hispanics were awarded an extra 1,000 points, whites were deducted 750 points, and Asians were deducted 1200 points. College students were automatically guaranteed graduation in their field, irrespective of their grades. Neither Spaniards, Cubans, or Argentinians qualified for the extra boost, however.

• Subjects like mathematics, grammar, empiricism, and science were racist disciplines.

• Equity was the most important thing. Everyone had to be equal. That way, everyone would be nice to each other. The result would be a better world.

These were not just the opinions of Pajama Jones. Oh, no. Authorities backed her up, she said, Authorities like:

• Asao Inoue of the University of Washington Tacoma who wrote that students’ written work should not be graded by quality, merit, or accuracy, but by the principles of Diversity, Inclusiveness, and Transgender Bathrooms.

• Laurie Rubel, professor of Brooklyn College had, indeed, declared that meritocracy was a racist idea, a tool of “whiteness.”

• David Johnson, deputy director at Stanford Social Innovation Review declared that we should not praise famous men and women, since the idea went against equality.

• Numerous studies had proven that meritocracy leads to selfishness.

• Natalie Warikoo of Harvard University had pointed out the fact that meritocracy in the realm of college admissions reproduced inequality.

Ordinarily, Cedric would have gone along with the standard tactic of staying in the background, as usual. Perhaps it was the irritating memory of the concert in the back of his mind, perhaps he remembered the school visit, but whatever the reason, a little imp told him to speak up.

“And, why . . . exactly . . . is inequality a bad thing?” he said in a challenging tone.

Stunned silence.

“After all, everything in the world is unequal. Animals are not equal to each other, not just between species, but within species. The same goes for plants. Plants are not equal. Animals are not equal. People are not equal. They’re different. There are differences. Some people are tall, some short, some average, some people are thin, short, medium, some are fat, or skinny, or strong, some people are attractive, some plain, and some just plain ugly to the bone. You say that diversity is good, you say. Well, there it is. You’re contradicting yourself. The whole idea of enforcing equality, that it exists but has been corrupted by . . . “whiteness” . . . and capitalism . . . is just plain stupid. I mean, seriously . . . one size fits all? I think not.”

“As a white man, you take your privileges for granted,” she responded. “Men and minorities have been marginalized and discriminated against in society for centuries, and-”

“Yeah, but now you’re talking about the past!” he quickly interrupted. “I’m talking about the present! No one’s denying that discrimination against minorities and women took place a century ago. No! But now? No way! You got women who commit crimes and are routinely given a slap on the wrist by the courts when they’re caught. They automatically get custody of children in divorces! Women are in every field of work. And blacks? We’ve got black Supreme Court judges, black mayors, black judges, black chiefs of police, black governors and black businessmen. We have black movie stars, basketball and football players whose individual annual salaries are more than the Gross National Product of some countries! Think I’m exaggerating? Look it up! Marginalized? I think not! The whole argument’s stupid! It’s a bunch of crap! What’s happening now is that race, homosexuality and women are being given priority over merit, talent, intelligence and grit!”

Cedric Chapman, Sr. was now on a roll, the words just pouring out, as if a dam had burst. Thoughts that had built up for a long time, but not allowed to be expressed now came rushing out, rolling over the “facilitator’s” attempt at interrupting the heresy.

“I have standards! And I hope others have too! If I go have an operation, I want the best surgeon to do my procedure, not someone who graduated at the bottom of his class. If I go to a restaurant, I want the best cook there to prepare my food, not a drunken idiot. If I fly on a plane, I want to make sure that the pilot’s a good pilot and sober and the plane was built by competent mechanics and engineers. I want quality in my life, not equality.”

“You need to check your white male privilege!” She finally got a word in. She was mad!

A pause. She had not countered any of his arguments, just voiced an incantation as if that would vanish him, and his facts, and his logic.

He stood up, pulled out the waist of his pants so he could see inside. “Yep, it’s there, all right. I checked. He says hi.”

A collective gasp was followed by raucous laughter.

Ms Pajama Jones, however, did not think it was the least bit funny. Infuriated, she turned around, grabbed the remaining handouts and waddled out of the room in a huff.

The colleagues around him erupted, some with applause, some with laughter, some with thumbs up. A couple of them came over and high-five’d him. “Dude, you the man! You the man, Cedric! You the man!’”

Chapman felt good. It felt good to express his convictions. He had expressed what had been suppressed in him—and apparently in his colleagues—for a long time. He felt lighter, with also a sense of relief.

“Well, I guess she’s not coming back,” someone pointed out eventually and they drifted out of the room, back to work, although a few stayed back, talking with Chapman.

After a while, he too returned to his office. As he walked back, he noticed some of the amused and approving looks he was getting from people he was passing in the hall who had not been in his meeting’s time slot. Apparently, word had gotten around fast.

He sat down in his office. After a few minutes, the telephone rang.

“Mister Chapman? HR would like for you to come down to their office.”

__________________________________

Armando Simón is a trilingual native of Cuba with degrees in history and psychology, and feelings of déjà vu. He is the author of several books (Very Peculiar Stories, When Evolution Stops, A Cuban from Kansas, and others).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast