by Pedro Blas González (May 2023)

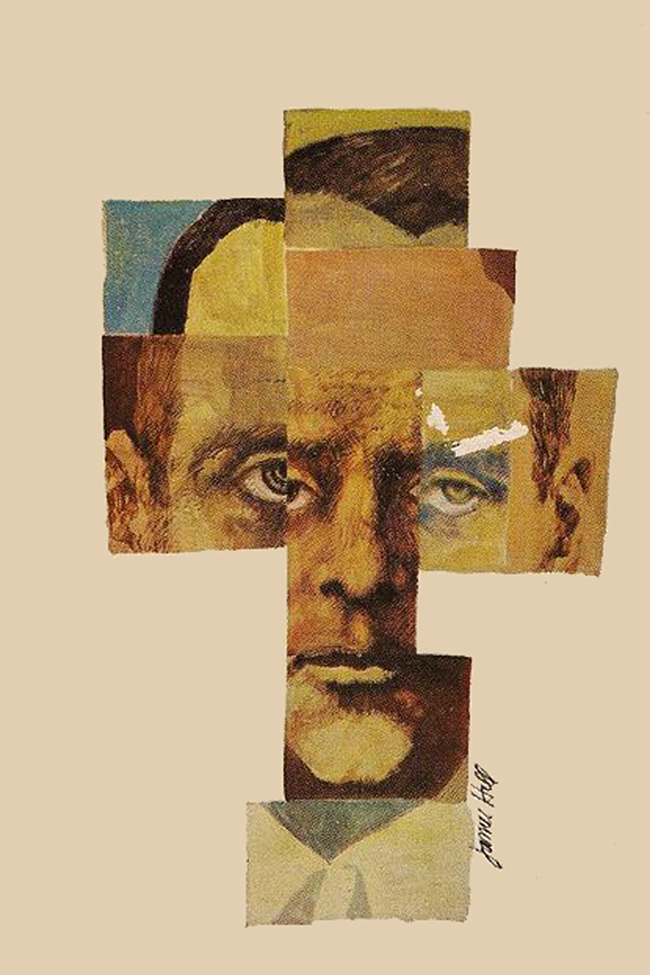

Death on the Installment Plan, James Hill (for Signet), 1966

It should appeal not only to man’s heart, intelligence, love of truth, but to the whole man; however pessimistic, it should help him to acquire an acceptance of life. A work excellent in other respects but inculcating a disgust with life is not great literature.—Robert Faurisson on Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night

After the rousing success that Louis Ferdinand Celine enjoyed with his first novel Journey to the End of the Night in 1932, the French author/physician published a sequel, Death on the Installment Plan, in 1936.

Regardless of how one qualifies Celine’s writing, daunting realism or responsible respect for objectivity, the time that has elapsed since the publication of his works has proven him right, even prophetic, about the acceleration of man’s moral decay.

Beginning with Celine’s lexicological style, the author’s signature use of the three dots … ellipses that convey motion, speech that is not encumbered by the rules and limitations of literary convention, is Celine’s recognition that speech is freer and more flexible than written language.

Written language can be likened to time. The past is only accessible through memory; one cannot return to the past. Locked into the present, and anticipating the future, written language ‘captures’ time in a literary sense by making it static for future verification, its objectivity a testament for all to ponder. This is commendable as long as one is conscientious of the need for objectivity and sincerity in writing.

Speech, on the other hand, is akin to space, where one can retrace one’s steps in a manner that offers dynamic correctives, verbal qualifiers that help us further explain ourselves. This is a luxury that speech affords us: “What I mean is … ” “In addition to what I said,” “Let me explain myself,” and so on.

Celine’s writing captures speech in its most organic fashion, thus creating havoc for his translators. Celine writes in the French spoken by unrefined people. He made it his literary mission to depict the language of the street in machine-gun bursts and colorful localisms.

The ellipses that characterize much of Celine’s novels made their appearance in force in Death on the Installment Plan. The ellipses generate attention to what is not said, what is left out, the incompleteness of any conversation, thoughts and conversations that trail off. Hence, the three dots …

‘Show Me Don’t Tell Me’ Chronicles of Life as Spectacle

Emotion, beliefs, and convictions play an important role in Celine’s work. Yet he eschews sentimentalism. He opts instead to offer a clear exposition of aspects of reality that cannot be ignored – the elephant in the room. The French author chronicles the lives and mores of people, their beliefs, and outlook on life, the world, and society.

Dissatisfied with the literary tradition of realism and naturalism, Celine ratcheted literature from what he considered the boundaries of the written word. The latter is an aspect of his thought and work that earned him the ire of critics and naysayers.

Death on the Installment Plan, or death by a thousand cuts is more than just the speech of a given people, in a particular locale and time. The story is a romp by the semi-autobiographical protagonist; Ferdinand’s rumble through the world. In effect, Celine’s novels offer readers a slice-of-life, life-as-spectacle rendition of man, society, and the world: a Dantesque, Bosch-like, Felliniesque reality that cannot be condensed by employing traditional literary conventions.

In Death on the Installment Plan Ferdinand offers a glimpse—this is an understatement—of his childhood, the events in his life that take place chronologically prior to adulthood, which he describes in detail in Journey to the End of the Night.

Celine’s novels are unmistakably picaresque, though, not by design. That is, they follow in the Spanish literary tradition of the picaro, a lowborn bohemian ‘picaresco’ character who moves around from place-to-place concocting ever-new schemes to swindle others. His characters are rogues who can barely function in society. The world that these characters make their own is a world of existential agitation and perennial displacement.

Considered in a literary vein, Celine’s novels can be stylistically characterized as avant-garde. For critics interested in form, Celine offers them much to criticize. We must keep in mind that the French author was not concerned with style, but rather with content. His vision of the world has little patience for literary style, which is the very thing that he shuns in literature. The most interesting aspect of his novels is their philosophical underpinning. Who are the people who populate his novels? What do they think about? How do they pass the time? Why do they live as they do? These are questions that fuel a long-standing understanding and appreciation of his work.

The first part of Death on the Installment Plan follows the trajectory of Ferdinand’s boyhood, when he lived with his parents. His father and mother are hardworking, industrious people. Ferdinand is a boy who keeps getting in trouble. His exploits are naughty and dangerous, but often hilarious.

Celine takes many liberties in writing about his childhood. His readers should take this with a grain of salt, for he understood that literature involves some degree of showmanship. Literature must simultaneously augment and condense reality. What matters most is to tell a coherent and moving story. While the boy in the novel has a strained relationship with his parents, especially his father, Celine’s own childhood, according to his biographical writings, was peaceful and loving.

Second Half of Death on the Installment Plan

The second half of the novel ramps up Ferdinand’s exploits in stellar proportion. Readers familiar with the carnival-like aspect of Fellini and Jacques Tati’s films will find a close resemblance with these cinematic gems and Celine’s literary imagination. Humor is also a central component of Celine’s novels. He satirizes life, man, and society like few writers can.

Ferdinand’s latest scam brings him into contact with Courtial des Pereires, balloonist, inventor, publisher of a magazine, and overall dabbler in all things scientific and timely. Courtial’s character is modelled after Henry de Graffigny, a French jack-of-all-trades, publisher of the scientific journal Eurêka, whose real name is Raoul Henri Clément Auguste Antoine Marquis. Celine met de Graffigny in 1918.

Ferdinand becomes Courtial’s secretary and right-hand man. The young Ferdinand takes the job without pay but is promised by Courtial that he will learn great things and have wonderful adventures. The adventures are plenty, mostly illegal and ruinous to Courtial’s finances.

Ferdinand is bamboozled into going along with Courtial’s latest, ever-more daring escapades partly because he does not want to return home and tell his parents about his latest ‘job.’ Ferdinand and Courtial are a tragic-comic duo trying to make it in the world, while continually being set back by the crushing weight of their own ambitions.

Awe and Wonder in Death on the Installment Plan: The Antidote for Postmodern Moral Degeneration

In Death on the Installment Plan Celine mixes his pessimistic rendition of human reality with life-affirming awe and wonder. In essence, the partnership of Ferdinand and Courtial presents readers with a vision of innocence that does battle with cynicism, hypocrisy, and affectation. The two partners fumble along while swindling others. Yet, for the most part, they never set out to do so. Courtial does indeed take young Ferdinand on wonderful flights of fancy, including teaching him about the beauty and grace of hot air ballooning.

The narrator describes Courtial in the following manner: “Courtial des Pereires, secretary, precursor, owner, founder of the Genitron, always had an answer to everything, he was never embarrassed or disconcerted, never maneuvered to gain time … His aplomb, his perfect competence, his irresistible optimism made him invulnerable to the worst assaults of the worst nitwits … Besides, he never put up with long conversations … ”

Nearly 600 pages long, Death ion the Installment Plan encapsulates aspects of the human condition that thoughtful and prescient readers who know how to read between the lines can easily attest to.

Celine makes readers come to him. His vision of modern man’s decay and moral corruption demands perspicuity and sincerity from readers. This is not best seller, easy chair reading. This is Celine’s legacy as a literary giant and thinker.

Table of Contents

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

One Response

Nice writing about Celine, a literary favorite of mine. Thanks.