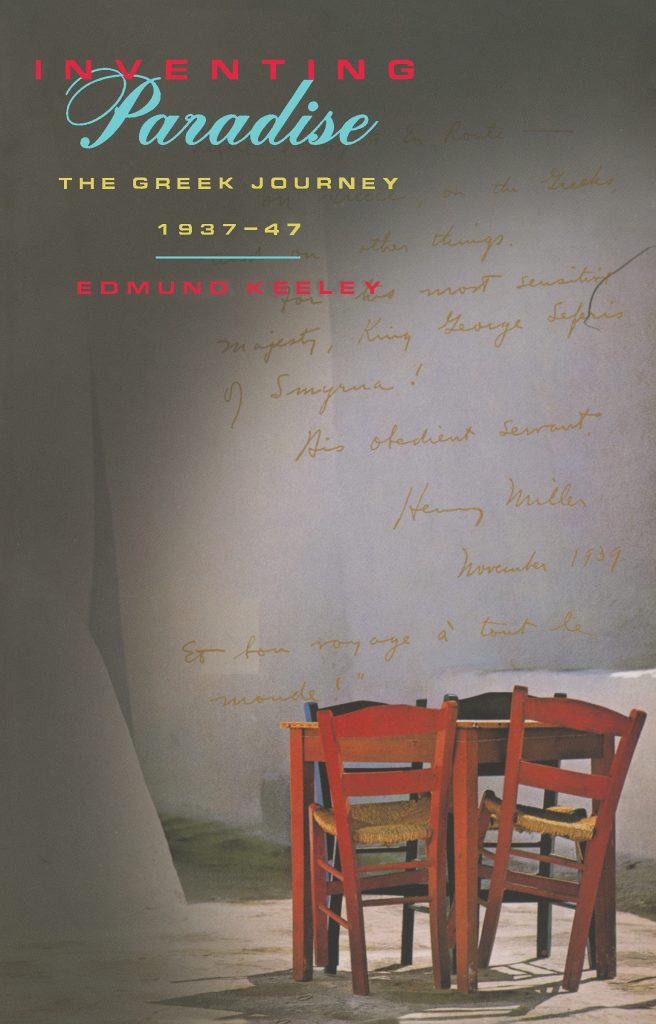

Character and Characters: Edmund Keeley’s Inventing Paradise

by David Solway (September 2022)

Two Friends, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, 1959

We enter a glade

whistling with lichen,

juniper and vetch;

thistle and vipergrass

hiss in wind,

and rockrose and hellebore,

and many other plants

whose names

we have forgotten.

______—Andreas Karavis, Saracen Island

For generations, centuries and millennia, Greece has been in the business of producing characters. The visitor who spends any amount of time there inevitably comes to feel like a kind of latter-day Theophrastus, author of the famous Characters, diligently recording the presence of, say, “The Chatterer” who is prone to delivering panegyrics on whatever may happen to come to mind or to spouting “long-winded, unconsidered talk” on “how full of foreigners Athens is getting.” Then we meet “The Inventor of News” adept at the “fabrication of false reports,” followed by “The Boaster” who flourishes “the letters he has received from Antipater inviting him to Macedonia.” No doubt Theophrastus would have found himself right at home with Katsimbalis, one of the heroes of Keeley’s deposition, or with that perambulating borborygm, Henry Miller, reveling in his proxy status, perhaps the central figure in Keeley’s book.

But producing characters is not the same thing as schooling character. Character is modest, consistent, self-communing, often inconspicuous, reserved, metriopathic, and very few of us can be said to be in possession of it. Being a character in the memorable sense of the phrase, however, is no piece of baclava either. It takes work, flair, discipline, a hospitality for self-contradiction, callousness and talent, and again very few of us can be said to rise above the level of personal nuisance or social irritant in the attempt to achieve that species of outrageousness that makes us writeable.

It is in this domain that Greece specializes, inventing a paradise—paradaisos originally signified a walled-in park or garden—of exotic specimens, great orchidaceous windbags, approximately tragic poets, endomorphic visionaries with a penchant for good cuisine, tormented elegists, and artesian rhapsodists whose mandate, as they see it, is to transform the dry and the mundane into the fertile and the unprecedented. The Irish of the Levant, they are practitioners of what Yeats in a confessional moment called “the emotion of plenitude,” that hallucination of feeling and personal greatness which deputizes for a plenitude of being most of us are no longer capable of experiencing. For this we owe them a debt of skeptical gratitude.

Any of us who have traveled or lived for a time in that garden of earthly and imaginary delights have met these marvelous aberrants. Among my own cherished memories are the taxi driver who set his vehicle aflame in Constitution Square to protest the rise in prices countenanced by the PASOK government, thus depriving himself of the livelihood he was defending; the young hotel clerk at the Lycabettus who regaled me at two in the morning with an hour-long lecture on those hardy perennials Tsis Elyot and Tsames Tsoyce; the Matalan poet who spent all his time reciting execrable verse as a prelude to seducing foreign girls and then fell from a cliff in mid-declamation, cutting short a promising career; and the Glyfada restaurateur who extracted a hardbound copy of Thus Spake Zarathustra from a till oily with currency notes, informing me in a conspiratorial whisper that he “taught theology on the side” and proceeding to demonstrate his lectorial prowess while the food grew cold.

Possibly the most glorious of these dreamers and inconsistents was the devoted lieutenant who, during another of those impending conflicts with Turkey, ordered his men to lay down a minefield in my front yard, threatening to blow up my children, then agreed to set up a plainly demarcated string pathway festooned with Narki signs which, should they ever have decided to cross the narrow straits, the Turks would have been able to decipher and negotiate as well as my children. Where else but in Greece?

***

Edmund Keeley is not altogether a character or at least not a flamboyant one but character is something he has plenty of. In Inventing Paradise, he offers in clear, measured, unpretentious prose—prose nerved with character—a fine and sympathetic account of the Generation of the Thirties—Seferis, Ghikas, Antoniou, Gatsos, Elytis among many others—who illumined the Greek landscape and its social milieu with beautiful paintings and imperishable poems and songs. But the star actors in the eccyclema he wheels out to mark the pathos, heroism and tragedy of the wartime and insurrectionary periods of modern Greek history are the grand Theophrastian talkers, namely Katsimbalis and the sojourning expatriates, Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller, especially Henry Miller. It is true that Seferis comes into sharper focus in the concluding pages of the book but the center of gravity remains with the boisterous declaimers, with those whom Theophrastus describes as being given to “singing in the public bath and driving hobnails into their shoes,” preoccupied with the sonic boom of their presence.

Edmund Keeley is not altogether a character or at least not a flamboyant one but character is something he has plenty of. In Inventing Paradise, he offers in clear, measured, unpretentious prose—prose nerved with character—a fine and sympathetic account of the Generation of the Thirties—Seferis, Ghikas, Antoniou, Gatsos, Elytis among many others—who illumined the Greek landscape and its social milieu with beautiful paintings and imperishable poems and songs. But the star actors in the eccyclema he wheels out to mark the pathos, heroism and tragedy of the wartime and insurrectionary periods of modern Greek history are the grand Theophrastian talkers, namely Katsimbalis and the sojourning expatriates, Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller, especially Henry Miller. It is true that Seferis comes into sharper focus in the concluding pages of the book but the center of gravity remains with the boisterous declaimers, with those whom Theophrastus describes as being given to “singing in the public bath and driving hobnails into their shoes,” preoccupied with the sonic boom of their presence.

Although much of what Keeley has to tell us is redundant and can be found wholesale in Seferis’ A Poet’s Journal, Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi and Durrell’s Prospero’s Cell—the last two in particular filled with “characters” (who are often amalgams of several originals) and with epic extravagances that eschew the arrogance of verification—we can understand his purpose with respect to his déraciné predecessors and what he calls “the inimitable first-person mode of my elders.” If Miller “had been building a mythical country from his first encounter with Athens,” if Durrell was one of those making room for “a new mode of imagining the country,” Keeley, another temp expatriate, is more concerned with remembering the inventors or, perhaps, to some degree re-inventing them as well as he goes on to recount their resonating exploits in the fabrication of paradise. He has written this book as the muniment of an authentic illusion. It is both title deed and defense of the glittering heterocosm invented by a small band of gifted writers, aesthetes and epicureans, even if—or because—it is no longer feasible except as a memory and as a personal inheritance, paradise now located somewhere behind the parietal bone where it may continue to flourish, though much less spectacularly.

The central theme of Inventing Paradise involves the concept of the mythmaker—the poet, the painter, the orator—who is driven by a profound intuition of the negligibleness of human existence and in consequence by the equally powerful need to make up for the paucity of the real, to repeal the constitutive deficits of experience through the exercise of the “mythmaking talent.” This is the true hero of Keeley’s memoir and explains the embedded chunks from other books in which the mythmaking faculty is highlighted, the wistful praise of “the imagination and will to make the country itself into a divine image that can reflect [the] many dazzling facets” of the human personality, even if such an image is unsustainable, and, finally, the scaling down and subsequent relocation of paradise to the bookshelf and the window-ledge, like a universe contained in a tiny locket. Keeley’s own talent is not as a mythmaker or an inventor but as a logothete, a preserver, a purveyor of miniatures of an enormous but now lost canvas, and of course as a celebrator of celebrators.

Now Katsimbalis and Miller are wonderful celebratory characters, noble impostors, stanchless raconteurs of imaginary epics that in any divine economy of the world should have been unimpeachably veridical. They practiced what we might call Creative History (on the model of Creative Accounting, which defers the logging of current expenditures to some hypothetical future date, endlessly deferred to avoid payment in the present). Such figures serve an indispensable social function in that they furnish an alternative world—a paradaisos—full of color and significance for those of us who continue to live in the humbler moral and domestic dimensions. That is, they enrich and diversify life for the less fortunate among us who are hampered by a conscience, whether literary or ethical, and doing so at the cost of moral substance and daily reliability which they seem infinitely capable of defraying.

Thus, they are more like forces of nature than actual people. This is why, I would presume, they prove so attractive or compelling for writers of Anglo-Saxon provenance (discounting the exceptions)—writers for whom, so to speak, the proliferation of characters may substitute for the sensed planular vacancies of “mere” character or the quieter charm of “mere” eccentricity, as, for example, in the case of Edward Lear. The Greek is the bee in the Anglo-Saxon bonnet, the honey-maker with a sting who both sweetens and needles the conventional imagination to exceed its customary velleities. The Greek takes us out of our melancholy cities, our suburban row houses, our button-down landscapes of desire where Shirley Valentines and Homer Thraces languish and despair. The Greek transports us into a paradaisos where we are invited to surrender to a brimming and aureate fiction protected by a wall of pictures, words, metaphors, narratives and erotic fabliaux (the literary kordax) that keeps reality at bay.

Or does it? It did not take very long, as Keeley laments, for the German tanks to level that wall and invest the garden, scattering its inhabitants to the sanctuaries of Egypt, the bunkers of the Epirus and the initial blandness of America. Imperative as the fiction of a praetum felicitatis may be, its walls constructed from the quarries of imagination and its flowers watered and tended by the love of the improbable, it does not hold unless love and imagination can find a way to accommodate the reality-principle and eros come to terms with thanatos. The individual must carry the garden within, render it portable, smuggle it across hostile borders bristling with the customs inspectors of the real, knowing that portions of it will have to be given up more often than not, but managing to preserve its essence from detection and confiscation.

And this is precisely the value of Keeley’s discrete and lovable book. Whereas Katsimbalis, that colossal blowhard, still provokes a grudging and nostalgic laugh among Athenian intellectuals (the kouskous is that the Colossus, himself something of a fraud, had a good time playing his credulous guests for innocents if not fools) and Miller remains a consummate liar blessed with vast rhetorical gifts beyond the ken of most professional scribblers, Keeley survives his infatuation with the characters and “mythmakers” who embellish his world, those plumed and ornamental virtuosos of the word, and by strength of character and a corresponding literary style graced by moderation and restraint, records for posterity an experiment in literary horticulture we must both celebrate and suspect.

Similarly, although there is something troubling about Seferis’ agonies and self-interrogations when he himself chose to leave Greece, benefiting from a kind of diplomatic immunity while his friends and relatives suffered under the German occupation, Keeley sends us primarily to the poetry and not to the biography. To put it another way, he helps us to remember the names of the plants which the inhabitants of Andreas Karavis’ Saracen Island have forgotten. He does not invent paradise but, behind a hedge of trimmed and decorous words—the batten exquisitely sheared to receive what remains of the sunlight—preserves the memory of a paradise that has been destructively invested. In this way he invests in its continued existence as an imaginative possibility although the world has ruled against it.

Inventing Paradise is a book well worth consulting not only for the committed Grecophile but for the common reader who wishes to see if it is possible to reconcile, like Keeley himself, the unsubstantiated effusions of unchecked imagination and the stringent predictabilities of the real—deception and recognition—or in a word, being a character and having one. A report on the luxuriant effects of paradisiacal declamation, it enables us to subsidize the floral illusion without one day, in an access of debilitating candor, having to declare bankruptcy.

David Solway’s latest book is Notes from a Derelict Culture, Black House Publishing, 2019, London. A CD of his original songs, Partial to Cain, appeared in 2019.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast