Chez le docteur

by Theodore Dalrymple (November 2022)

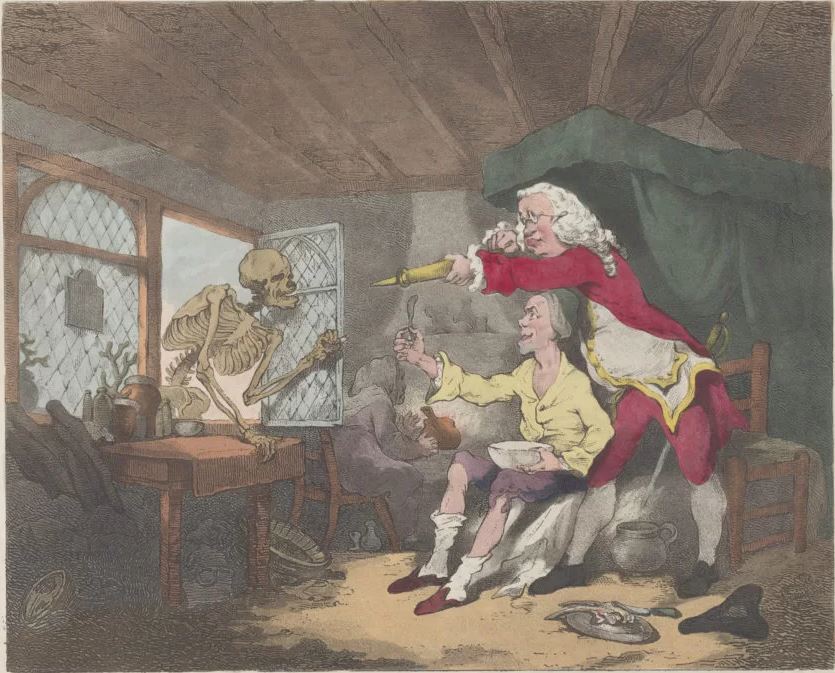

The Doctor Dismissing Death, Peter Simon, 1785

In France, thousands of health workers have demonstrated about the deficiencies of the French health care system and its unpreparedness in the face of the Covid epidemic: and this despite the fact that France spends a larger proportion of its GDP on health care than any other country in Europe.

France was where the sanctimonious clapping of healthcare workers during the epidemic began. Every evening, at 8 o’clock, people would go to their windows, balconies or terraces, and applaud the healthcare workers who were caring for the sick hospitals, at some risk to their own lives. It was not completely useless, since it allowed me to get to know my neighbours in Paris a little. But heroism or devotion to duty applauded while it is taking place easily turns it into something else, exhibitionism for example, and promotes that most dangerous and long-lasting of emotions, self-pity.

The applause found its echo across the Channel because the British love sanctimony, and in fact are very talented at it. I am the last to deny that doctors, nurses and others did their duty during the epidemic, again at some risk to themselves. I doubt that many of them gave other than of their best in the difficult situation in which they found themselves. This, of course, was true in many other countries, not just in Britain.

It is precisely because the staff of other countries were as devoted as the British that I found the praise of the NHS nauseatingly self-congratulatory as well as entirely misplaced. Staff behaved well not thanks the NHS, but because, in such situations, as Adam Smith put it, how selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it. In a word, goodwill.

My admiration of the NHS has its limits. It is not as atrocious as its most ardent detractors would allege, but neither is it the miracle-working virgin that its worshippers like to pretend, and that the applause for it during the height of the epidemic would have suggested.

For example, if I want to see a doctor when I am in England, it is easier, quicker and more pleasant for me to go to Paris than to see a doctor in the large practice three hundred yards away from my house. For one thing, I will not be humiliated by a gorgon-receptionist who will treat me as if I were a malingerer attempting to extract by fraud something to which I was not entitled, despite the fact, easily available to her, that I do not attend more than once a year and usually less often than that. In France, I will not have to explain in advance why I want to see the doctor: there, that is still something between the doctor and the patient and not a matter of moral triage. In France, I do not have to prove that I am worthy to see the doctor. True, I have to pay, but not very much, about the cost of three pints of beer and well within my means.

The unpleasant aspects of health care in Britain are universally acknowledged, are well-known, and a cause of wonderment to all Western Europeans. I have come to the conclusion, however, that it is precisely these aspects that appeal so strongly to the British. How else is fairness to be guaranteed, other than by ensuring that everyone is humiliated and made to feel that he is privileged to receive anything at all?

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast