Christmas Ennui

by Larry McCloskey (January 2023)

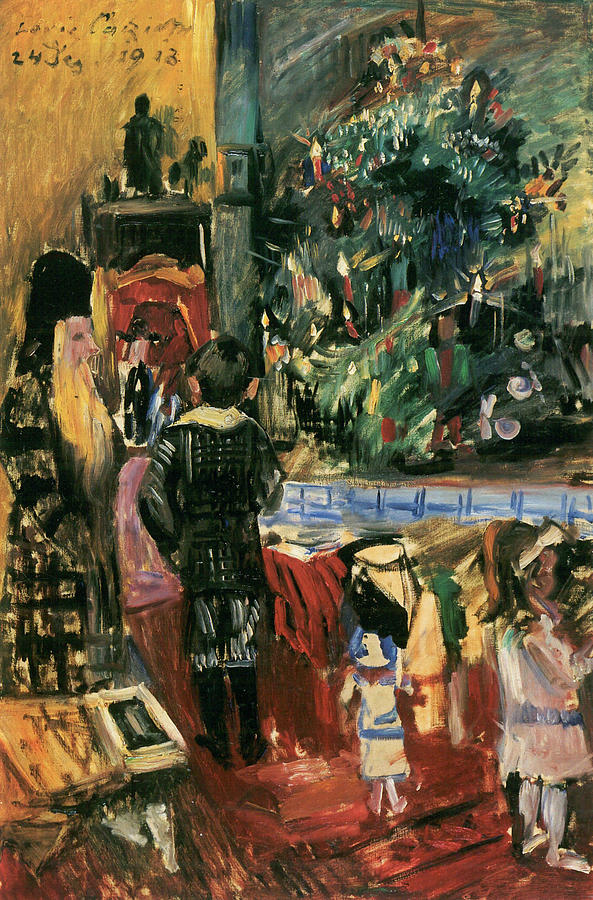

Christmas Present, Lovis Corinth, 1913

In How the Grinch Stole Christmas—that is, the animated 1966 film version narrated by Boris Karloff—the Grinch’s plan to steal the material hustings of Christmas is nullified by the great coming together of people in the festive holy moment (and what could be holier than when the Grinch even got to carve the roast beast?)

In the days leading up to the one-time screening of The Grinch on one of our two lonely television channels, we paid close attention so as not to miss it. It was an event, we watched it together, and the message was easily absorbed because in the act of watching we replicated the Whos of Whoville, minus some of their weird styles. (Wait, I take that back, this being the fashion apocalyptic 1960’s after all). In our family of eight—with a late and unexpected ninth on the horizon as was the Irish Catholic way—Christmas had many rituals and little material significance. We didn’t know it was possible to receive gifts in the plural, though Christmas traditions were boundless. There were Christmas concerts to prepare for, and Sister Mary Claire who conducted the choir was an exacting task master. There were presents to buy (so we did know of the existence of plural in the giving direction). There were Christmas holidays to plan for, with winter no respite from running wild in the hood without parental scrutiny from any of the families that lined our streets. The Christmas tree had to be selected and decorated, occasionally as late as Christmas Eve, and with the setting of the sun and the lighting of the tree Christmas magic was finally unleashed.

Mom wanted us to nap before midnight mass, and we complied by laying down on our beds, together, giggling and making corny jokes. We always did what we were told, but napping was never going to happen. After the requisite time served, we got up, wiped the smiles off our faces and joined mom and dad and an array of guests who popped in for ryes and coke throughout the long, festive evening. Stanton’s, Kennedy’s, Kelly’s and Brennan’s populated our living room, so yes, my parents were that clannish, and our circle of mainly Catholic and Irish, that narrow. Even today, I describe our Irish clan as less well-bred than in-bred. Okay, so somewhat facetious, but in the age of disparagement, seems fitting.

The church was over-flowing for midnight mass, with the many lookers and hangers-on spilling out into the night air and fresh snow. And it is probably because of this unusual church configuration that I came to endure my great shame. To my everlasting grief, I was chosen to sing solo at, first the Christmas concert, and then to my great terror, I was chosen to the walk down the aisle with the priest and small choir to begin midnight mass. The concert solo in the church basement passed with some trepidation and little incident, but the midnight mass conga-line had to pass through a mass of humanity and I had not been gifted a calming rye and coke. The chosen piece was “Oh Come All Ye Faithful,” with the choir singing the “joyful and triumphant” section, and my task to solo the refrain “Oh Come Let Us Adore Him.” Except I was not joyful and triumphant. Apparently, my pre-adolescent voice that sounded sweat and clear in front of Sister Mary Claire, was completely lost to the crowd, to the open doors, to the wind and swirling snow, not sure, but I could not project my voice, was unheard, and as I placed the baby Jesus into the manger on the pillow I had carefully balanced throughout the church aisle tour, I reddened with shame. Adults tend to forget or not see the shame kids are capable of, for no particular reason.

That is, until Mass ended and we continued on to our Christmas Eve tradition of post church take-out Chinese food. To this day, I have no idea how this strange tradition came to be. We wee ones who never stayed up later than 9pm, and never, ever had take-out food of any stripe, had both extravagances thrust upon us, and oddly, in the celebration and on the occasion of Christ’s birth. This was my dad’s doing, and he being as predictable as the setting sun, we luxuriated in the dissonance between the colour of Christmas Eve and the grayness of the rest of the year. Surely the world’s most exciting tradition, we thought. Trite as it may seem, dad’s out of character tradition perhaps teaches us to never lose the capacity to surprise or be surprised by people we know well. Especially those we know well.

For 55 years, the Whos of Whoville’s togetherness has reminded us—even if slightly upstaged by the Grinch’s long suffering mutt Max—what the Christmas spirit really means. Problem is, this short Dr. Seuss classic has become as bittersweet as—dare I say the word—Christmas. Somehow progressives decided that the great tidal-wave of inclusion necessitated the exclusion of western culture and religion, to the confusion, I might add, of many people of newly included status.

Years ago a young woman who worked for me in the university got tired of the self-inflicted disparagement of all things Christmas and Christian, and undertook to organise our office Christmas party. She was unusual both for calling for it a Christmas party—with features such as ‘tree’ also prefixed by the word Christmas—as well as the fact that she was and is a devout Muslim. She was wise beyond her years. I suspect many newly included peoples of diverse religions and cultures wonder at the progressives’ haste to exterminate themselves. Makes you wonder as they wonder which is a funny thing to come together and wonder about.

I took an interest in convent life as my esteemed Aunt Isobell —65 years a nun, mostly at Mount St. Joseph, Peterborough—withered and shrunk with age. She’d been nicknamed ‘moose’ as a child because in cresting 5’2’, she was taller than her older sister Mary. When we were children we didn’t know her, were intimidated by her formal habit and stoic ways, but as we got older we inexplicably became smarter and saw her for the first time. Turns out Mark Twain was right, and she was warm, funny and good company. So my wife and I began visiting her in Peterborough and, it being a long drive, Aunt Isobell arranged for us to sleep over at the convent which we did which resulted in us becoming even smarter as the years passed. Or less stupid. Or at least less biased.

We met many nuns, and if I may stereotype for a moment, they were uniformly refreshing for their ability to defy stereotype. They were worldly, had well-informed opinions on, well, everything and, for life of me, I never met one nun who looked her age. I resisted the temptation to ask about their nightly moisturizer or anti-aging cream. They looked younger and died later than the general population and, though I might be accused of exaggeration, they seemed more content and had greater purpose than the rest of us. They were happy—perhaps not in the modern sense of fulfillment of all want and desires (in other words impossible to fulfill)—but in the rational, devotional sense of not thinking about happiness as the means for being so. Or at least refusing to be unhappy. Modernity, writhing in the cesspool of meaninglessness and poor mental health, would be wise to take note. Like most things of value, their’s was not a formula, a solution, or secret cold cream; rather the road less travelled often pays greater dividends than the path of least resistance.

In recent decades, convent life has become uncool, has been universally disparaged, and with long-living nuns dying off without new blood to replace them, convent life has become extinct. Everywhere. Without notice or anyone noticing. My aunt died younger than most at 88, and magnificent Mount St. Joseph was sold off. Convent life today, if given any consideration, is considered an archaic relic of our exploitive, sinful past. (Never mind that early schools and hospitals were primarily staffed by volunteer nuns. That is, convents didn’t just contribute to services essential to life from the cradle to the grave, they were it). Though I can’t explain it, I’ve witnessed the unassuming, intangible power of convent life and the nuns who were its life until they and their vocation were rendered lifeless. I’ll maintain, to my dying day, they knew something, a life’s something that has been lost that matters, but can’t be proven. In the scientific materialist world into which we are presently held captive, what cannot be seen, heard, or scratched, cannot be real.

Christian churches are not far behind convents in the societal dance towards cancellation, with a mighty contribution from the actions and lack of action of some religious leaders in recent decades. Those churches that have not been sold and re-purposed as condos are mostly empty now. Except for Christmas. People will still crowd in for their nostalgic hour, and for the truly devout, maybe again at Easter. And for that one hour, we want to feel, taste, and believe in the remnants of a spiritual existence before exiting with a vague hope of resurrecting the feeling again, perhaps with more belief, next year.

Still, it is the lead-up to Christmas that is the most perplexing. After Hallowe’en, Christmas music and adornments flood the shopping malls and coffee shops, that are our modern, surrogate churches. We are blasted with themes of togetherness, family and meaningful ritual, even as we huddle on our very individual, divisive devices and narcissistic preoccupations. The notion of togetherness outside our tribe doesn’t resonate for those fighting for inclusion into what they already have or belong to, or maybe against exclusion from something they don’t really want to belong to. Or perhaps there is a human right we missed, an individual entitlement to which we feel entitled, a something someone got that we didn’t.

Christmas was once a time away from school, obligations, the material world, and the need to make a buck. It was a celebration, an acknowledgement or expansion of the life we lived or aspired to; whereas today if you bother to listen to Christmas lyrics, they represent another and archaic world, a fantasy, a weirdness we don’t understand or care to know. Walking the mall, we may vaguely recognize the tune, barely notice the Christmas schlock we’ve heard a thousand times.

In trying to reconcile trailing clouds of glory with the blank stare in the mall, we feel the disconnected creep of ubiquitous, meaningless Christmas. How else to explain the low grade depression and vague sense of guilt for feeling unhappy during the season of expected happiness.

Still, for some, there is Christmas magic in the still night air. The great collective pause that shuts down most of western civilization for the space of 36 hours can still move us to communion, to gratitude, to awareness of something that matters both now and beyond the pale.

If Christmas celebrates anything, if this life matters, if there is anything after death, it will not be revealed as a progressive Utopia. It won’t be a future where all equity outcomes are realized. It won’t even be about the future. Or at least we shouldn’t look forward to find it. Truth is more likely in buried in the past, in memory, in the nostalgic’s lament. The measly gift under the tree that delighted, or that cruddy Christmas dinner with family members once estranged, or that time we worked up the courage to say what needed to be said to she who needed to hear it, even if she wasn’t listening. This is the past before the trifecta of pain and loss and death, that was the potential embodiment of heaven if only we could see it, that we will return to in taking our place in the Whoville circle where we belong.

So, there is hope for those who’s sense of humanity includes humans. There is transcendence, there is God, and there is the possibility, in this very moment, to move from blank stare to Whoville engagement. We have to be deliberate, persistent, gazing into the eyes of a loved one we’ve looked at a thousand times, and seeing for the first time. We have to shake off ennui for belief in the possibly of an awakening (but not awokening) from the reality of death that is about to descend upon us, whatever our age. Because if nothing follows, nothing has context, nothing is real and the survival of the fittest mentality that has woken within us will be the rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem to be born.

Table of Contents

Larry McCloskey has had eight books published, six young adult as well as two recent non-fiction books. Lament for Spilt Porter and Inarticulate Speech of the Heart (2018 & 2020 respectively) won national Word Guild awards. Inarticulate won best Canadian manuscript in 2020 and recently won a second Word Guild Award as a published work. He recently retired as Director of the Paul Menton Centre for Students with Disabilities, Carleton University. Since then, he has written a satirical novel entitled The University of Lost Causes, and has qualified as a Psychotherapist. He lives in Canada with his three daughters, two dogs, and last, but far from least, one wife.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast