by John Tangney (August 2018)

In Plato’s Cave No.1, Robert Motherwell, 1972

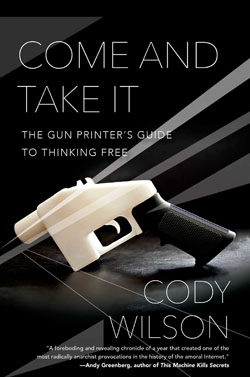

Cody Wilson was a law student at University of Texas-Austin when he decided to start printing guns using a 3D printer he ordered from a company called Stratasys. When the company found out what he was up to it repossessed the printer, but he persevered and, after much trial and error, his own company, Defense Distributed, successfully used a Stratasys printer to make a single-shot pistol that he called The Liberator. He was legally prevented from publishing the software needed to operate the printer, and the chapter describing the assembly process in the book he wrote about it was redacted for legal reasons, underlining the fact that this was a highly political publishing event.

For Wilson, the political is the personal; and Come and Take It is a work of autopoesis as much as it is a political tract. It pays great attention to the weather as a cinematic backdrop to the writer’s road trips to various gun dealers, engineers, and firing ranges around Austin. He also traveled to Europe to hang out with bitcoin radicals and court a Russian oligarch. The Liberator is framed as the end product of a journey from vanilla liberalism to post-leftist, crypto-anarchism, driven by disgust with the herd-instincts of his fellow citizens. These foils to his anarchist rebellion appear as hipster extras populating the UT lecture halls and the diners he visits late at night around Austin.

For Wilson, the political is the personal; and Come and Take It is a work of autopoesis as much as it is a political tract. It pays great attention to the weather as a cinematic backdrop to the writer’s road trips to various gun dealers, engineers, and firing ranges around Austin. He also traveled to Europe to hang out with bitcoin radicals and court a Russian oligarch. The Liberator is framed as the end product of a journey from vanilla liberalism to post-leftist, crypto-anarchism, driven by disgust with the herd-instincts of his fellow citizens. These foils to his anarchist rebellion appear as hipster extras populating the UT lecture halls and the diners he visits late at night around Austin.

The narrative is elliptical, fragmentary; the central character romantically self-involved, and the ancillary protagonists hard to keep track of because they’re sketched so perfunctorily. It also contains political musings that encourage us to think about the era of printable guns as a return to the sources of the Reformation from which modernity and the United States first sprang. The kind of political subjectivity that emerged in the 16th century from the new religious emphasis on individual conscience, and the democratization of knowledge through the printing press, has today been co-opted by the mass media. Wilson describes life in this dispensation as characterized by “the boredom of paradise,”[1] positioning himself as exactly what Francis Fukuyama feared when he remarked in The End of History and the Last Man, that boredom rather than political revolution might be what undoes the neo-liberal millennium.[2]

For Wilson the two are connected. Today’s universities, the political party system, and their media allies represent homogenizing globalism and ethical universalism, against which is pitted the “dark magic of sectarianism.”[3] The culture war of many fronts in which they are engaged represents the decadence of the long drawn-out revolution that began with Gutenberg and Luther. Meanwhile, Wilson’s personal journey of disaffection draws on his undergraduate reading in continental philosophy to suggest that the arrival of the printable gun is a kind of unearthing of the thing in itself hidden behind the depthless phenomena of postmodernity, which is perhaps his way of admitting that what he’s distributing is an instrument of death. His autopoetic narrative about it is a self-undoing. At the end of the book, as he fires the gun in front of a BBC camera crew, he says he doesn’t know who he is any more, which sounds like a claim to have escaped from all of the available political identities in contemporary America.

In the early stages of its development the single-shot printable gun was more potent as a symbol of individual resistance to the various modern institutions that Mencius Moldbug collectively terms “The Cathedral” than for any real power it conferred on ordinary people. Indeed, Moldbug makes a cameo appearance in the book, in which he chides Wilson for his media-whoring and implies that his anarchist idealism is an adolescent phase, and that what it really hides is a frustrated will-to-power. Wilson records this conversation by way of keeping an open mind about what his real motives are and suggests that as a right-wing anarchist he doesn’t care whether his idealism is pure egoism.

He claims the printed gun is a metaphysical attack on the religious sense of control provided by the state, and the way he mingles the language of metaphysics and ‘me, me, me’ makes it hard to determine whether there is any moral center to the book. Though it was reaching for something like Wordworth’s “egotistical sublime”[4] it often reminded me of Thomas Harris’s Hannibal in which the detective and the killer finally elope to Argentina, obliterating the line between good and evil so that the narrative no longer stands on any kind of moral ground; it becomes unrealistic, light and empty. Or does it just enter a different moral universe?

Banned from Patreon and rejected by the Maker movement, Wilson has founded an alternative crowdfunding site called Hatreon that is currently blocked from receiving donations. In this and other ways he distances himself from ersatz methods of recovering authenticity that are palatable to the Cathedral faithful. Rather than a moral vacuum, it could be that this is what moral courage looks like to those who don’t have much of it, if we understand moral courage as an ability to remain true to yourself when you’re in a minority of one. However, Wilson isn’t quite that isolated despite his best efforts to mythologize himself as a singular phenomenon, as the community of likeminded anarchists around him shows.

His comments about Donald Trump in this video are informative about Wilson’s type of libertarian mentality. Although it’s not clear that he supports Trump or identifies with the forces of conservative nationalism that propelled him to the White House, he admires him for being “alone in his singularity,” thinks there’s something atavistic, childlike, and pure about him. He has a “perfect reflectivity” that makes him inscrutable as a myth, as he manipulates the media and defies political protocol in the run up to the 2016 election. The mystery of Trump’s inner life, if he has one, is different from the highly literate mystique that Wilson creates around himself, but in both cases, there is an admiration for maverick individualism.

After writing Come and Take It, Wilson’s ability to print guns was tied up in more red tape and he became embroiled in a lawsuit with the US State Department about whether the ban on publishing gun-printing instructions on the internet violated his first amendment rights. However, his company continued to do research and development in the field of printable weapons, selling an automatic machine-tooling product called the Ghost Gunner that can finish AR-15 parts to military specifications. Now, under the Trump administration, he has been cleared to print his instructions; an interesting development at a moment when some people claim that America is already in the early stages of a second civil war.

Even before the civil war theme became common in the media, Wilson was described by Wired magazine as one of the most dangerous people on the planet, though to other crypto-anarchist types he is in the vanguard of anti-statist activism, and an extreme test-case for issues of free speech. Allowing him to make information about how to print a gun available on the internet is not the same as allowing someone to cry “Fire!” in a crowded theater. It’s a legal scenario John Stuart Mill never dreamed of that, for better or worse, has now become a reality. In bringing gun-printing under the aegis of the first amendment, Trump’s State Department has made it more unlikely than ever that enemies of the second amendment will achieve their goal any time soon.

***

(August 1, 2018) Addendum: The State Department’s green light for Wilson to publish his software has woken the legal establishment up to the significance of the ghost gun. He was blocked at the eleventh hour by Clinton nominee, Seattle District Judge Robert S. Lasnik, from proceeding with his plans. President Trump, hedging his bets and attempting to stay on the right side of the issue, suggested in a tweet that after consultation with the NRA he is provisionally of the opinion that printed guns are not a good idea. The fact that the President is taking advice from the NRA rather than from law enforcement, is presumably meant to signal to his base that his doubts about 3D guns don’t represent doubts about the 2nd amendment. At the same time it signals to monied interests in the weapons industry that their business isn’t in jeopardy.

[1] Cody Wilson, Come and Take It: The Gun Printer’s Guide to Thinking Free (New York: Gallery Press, 2016) e-book edition, 65.

[2] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York:Free Press, 2006), 330

[3] Wilson, 94

[4] A phrase coined by John Keats in 1818

_____________________________________

John Tangney is originally from Ireland. He has a Ph.D in English from Duke University, and currently teaches in Russia at the University of Tyumen. His recent essays can be found in Literary Imagination, Litteraria Pragensia, Bright Lights Film Journal, Religion and the Arts, and The Time Traveller.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link