Collectivism and Contradiction

By Emina Melonic (May 2018)

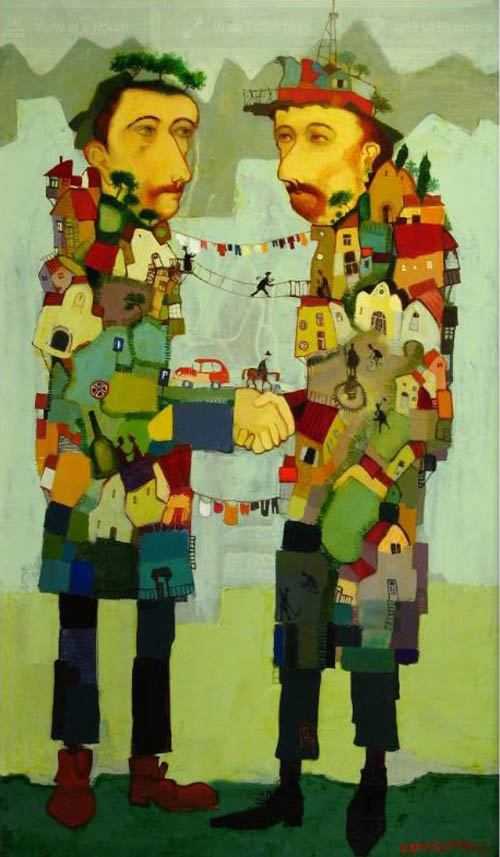

Meeting, Otar Imerlishvili, 2009

.jpg) he phenomenon of collectivism is nothing new. It has always existed in some form or other, at times both harmful and harmless. Collectivism does the most damage to the order of things when it becomes a political reality, such as we have seen with National Socialism and Communism. Both ideologies not only contributed to the erosion of the society that values ethics but its proponents committed mass murder and genocide—all in the name of collectivist unity that was supposedly meant to bring people together.

he phenomenon of collectivism is nothing new. It has always existed in some form or other, at times both harmful and harmless. Collectivism does the most damage to the order of things when it becomes a political reality, such as we have seen with National Socialism and Communism. Both ideologies not only contributed to the erosion of the society that values ethics but its proponents committed mass murder and genocide—all in the name of collectivist unity that was supposedly meant to bring people together.

Collectivism has an entirely different form in our present time; it is insidious because it revels in the ambiguity of concepts. Without a doubt, people have a desire to be part of a larger reality and sometimes this desire is born out of good intentions. But the failure of such naïve people lies in an inability to see the difference between a collective and a community. The intellectual and societal neglect of this rather large and important distinction has created a totalitarian monster originating mostly from a mutated version of Marxism and the newly formed globalist ideology. Today, “conquering the world” means eradicating the society which values both the good and the beautiful under the guise of compassion, care, and a so-called “one-world togetherness.” Paradoxically, this obsession and leftist fetish has created a society that promotes diversity as long as that diversity fits into a particular ideological category which makes a distinction between “us” and “them.” The same people who say that they despise such a negative differentiation between human beings are the very same who engage in marginalization of people they deem to be inadequate, wrong, or evil.

In order to further illuminate what kind of collectivism we are faced with, it is necessary to briefly mention what constitutes a “collective” and what constitutes a “community.” Any ideology denies the existence of individualism and embraces the pretense that a collective is the same as a community. This is wrong.

In a collective, an individual has no capability to make his own decisions and choices because that requires targeted and precise deliberation. The only choice (again, paradoxically) such an individual can make is to cease having control over his own decisions. This is a rather dangerous metaphysical game because, in that one act, such an individual has chosen to lose the inherent humanity present in all of us. In effect, he has chosen to dehumanize himself by seeking the meaning of personal identity from a collective that does not, nor will it ever, have a human face.

By contrast, the creation of any community (whether it is religious, cultural, or otherwise) depends on the individuality of each person. If he chooses to be part of a community, an individual brings uniqueness into the fold, which contributes to the idea and action of human flourishment. Both the individual and the community is perpetually humanized because each person remains autonomous and free.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that a community is free of conflict. On the contrary, precisely because of the difference between individuals, we experience and witness tensions—but also resolutions. Being free means being responsible and accepting the truth that individuals can disagree on some matters. However, unlike a collective, a community by its definition creates a space of freedom in which no individual is compelled or coerced into any action that demands the loss of the autonomous self.

It is hardly surprising that so many contradictions and paradoxes have emerged given the public dominance of globalist ideology and identity politics. A globalist mind is determined to annihilate the sovereignty of nations (especially Western countries), creating a borderless world and, by implication, this goal extends to the interior lives of people. Sovereignty of the self is anathema to globalist ideology, which is why the oppressiveness of identity politics makes an appropriate bedfellow of globalism.

Relying only on selective particular identities, proponents of identity politics further fragment the individual relationship. In their worldview, one can be everything and nothing at the same time, especially if realities such as gender or culture are involved and, more importantly, if this worldview involves a distortion, fragmentation, and destruction of order and history.

Despite the fact that both globalist ideology and identity politics are contributing factors to the daily contradictory state of being, at the center of this problem is a skewed sense of one’s interior life. Perhaps it is a lack of an examined life that leads to the distorted view of others. Examining one’s life means that one has acknowledged the existence of an interior life, which is made up of reason, thinking, judging, and feeling. Allowing oneself to be part of the collective and slowly but surely disappearing within it, one reverts into a form of primitive emotionalism. Surely emotions are a necessary and important part of our lives, you might say! Naturally, they are. As philosopher Martha Nussbaum notes in her book Upheavals of Thought (2001), “Emotions shape the landscape of our mental and social lives.” Emotions can be intelligent if they are based on fundamental and universal values. Anger can be borne out of a sense and need for justice. Love can grow from tiny seeds of passion. Emotions can also engender empathy for a fellow human being, and thus result in ethical behavior. After all, it isn’t merely an intellect that decides what is good and what is evil. An emotional experience can contain truth and is just as important as a logical system of reasoning. But what happens when emotions, which are inherently part of our interior lives, morph into a primitive response to the realities of the world?

The roots of primitive emotionalism are found in the ideologically charged repetitions that call on us to simply react without a hint of reflection on ourselves or others. Ideology is a denial of being and often masquerades as philosophy.

One of the fruits of primitive emotionalism is an excess of false empathy. This type of empathy is false because it uses ideology as its lens through which the world is viewed. As Hannah Arendt observed in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), “Ideologies are never interested in the miracle of being (469),” and neither is false empathy. Ultimately, it is self-serving, caring only for the giver of compassion. In this pseudo-metaphysical game, the recipient of compassion is irrelevant and almost accidental. What is more important is how the giver will feel after the compassion has been given.

The objective of primitive emotionalism is to merely create the conditions of empathy that endlessly repeat themselves, and to not actually offer any solutions or help to the injured party. The intrinsic narcissism that results from it is only capable of creating a recurrence of mindless ideological slogans and inevitably treats every human being as a political or social entity. There is no “humanity” in “human being” according to this line of “feeling” and “thinking” because the goal is not to have compassion, but rather to have the appearance of it.

If something as important as another’s humanity is just a manufactured simulacrum to be used for the purposes of a coercive ideology, then it shouldn’t come as a surprise that human beings are seen and treated as concepts and abstractions and not as fully embodied beings that possess souls. If the majority of people are falsely living in synthetically created identities free of universal human values, then why should we be surprised that the current modern reality is made up of nihilistic paradoxes that negate the strength of an individual human spirit? How can we expect to relate to each other in an authentic encounter when all we see are illusions of being?

This brings us to a rather depressing conclusionthe loss of metaphysics. As mentioned earlier, ideology’s main purpose is to deny the individual being and to pose as an open-minded philosophical construct. In other words, to present itself to the world as metaphysical reality, when in fact, it derives its meaning from the denial of being. This may seem like a peripheral issue but the existence of a sovereign individual wholly depends upon the society’s implicit or explicit affirmation of being. If an individual is denied his own sovereignty, then what role or voice can he have in a supposedly free society other than that of a voiceless prisoner of collectivism?

We live in strange times of soft totalitarianism that solely rely on theoretical ambiguities that give rise to an infinite regression of destructive paradoxes and contradictions. The varieties of simulacra that we see on a daily basis create false impressions and as such render our relationships to each other false as well. The only way out is through real human encounters in which we stand face to face.

______________________________

Emina Melonic has been published in The New Criterion, Splice Today, National Review, The Imaginative Conservative, and American Greatness, among others. You may follow her on Twitter @EminaMelonic.

Articles by Emina Melonic.

Please help support New English Review here.