by Marc Epstein (October 2018)

The Investigation, George Condo, 2017

I write this just as former Secretary of State John Kerry has returned from Tehran, after colluding with the Iranian foreign minister. Kerry admitted to meeting with Javad Zarif, his chief negotiating partner in the now-voided Iranian nuclear deal, on at least three occasions since leaving office.

Meanwhile accusations of Russian-Trump collusion for the purpose of manipulating the outcome of the US presidential election have continued to hang around the neck of the American body politic for close to two years.

Robert Mueller, a former FBI director, has been charged by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein to ascertain if members of the Trump campaign “colluded” with Russian operatives to manipulate the election results in favor of candidate Donald Trump. The Democratic opposition, along with like-minded confreres in the media view Trump’s victory as an unprecedented assault on our democracy.

For reasons unexplained, Rod Rosenstein chose the term collude, which is absent from the Federal criminal code, instead of conspire, a defined crime. Rosenstein’s legal malapropism has only muddied the waters and hence confused lawyers, the press, and public alike.

In fact, charges of improper collusion with a foreign power are as old as the Citizen Genet Affair of 1793. But we need not travel that far back in time in order to find other examples of collusion and conspiracy scandals that occupied the minds of our elected representatives and the Washington press corps. It foreshadowed our current collusion contretemps.

A more recent example of “collusion” is described in Arnold Offner’s new biography of Hubert Humphrey, Hubert Humphrey: The Conscience of the Country. It occurred when Republican candidate Richard Nixon opened a back channel to the South Vietnamese and urged them to hold off making a peace deal until after the election. Nixon promised them a better deal should he win. LBJ kept the information to himself and Humphrey went on to lose to Nixon by a razor thin margin.

In 1991, Gary Sick, writing in a New York Times op-ed, The Election Story Of The Decade (April 15, 1991), charged that the Reagan campaign colluded with the Iranians to ensure that, in return for arms, the Iranians would hold off releasing the American embassy hostages until after the election. His book, October Surprise: America’s Hostages In Iran and The Election of Ronald Reagan, rehearsed a theory first advanced by Lyndon Larouch after the Reagan landslide.

Sick had been Jimmy Carter’s Iran advisor and member of his National Security Council. The Iran-Contra scandal that erupted in 1985, “breathed new life” into the charge and gained widespread support in the media.

Lloyd Cutler, White House counsel to Jimmy Carter, articulated just what the proper response to Sick’s assertions should be in a follow-up op-ed in the Times just a month after Sick leveled his charge. Just plug in Trump in place of Reagan and you’ll see just how the game is played.

Despite these reasons for skepticism, it is important to learn, if we can, whether anyone in the Reagan campaign tried to interfere with the hostage negotiations and how members of the team reacted to any bait the Hashemi brothers or others may have dangled before them. Even without the testimony of Mr. Casey and Cyrus Hashemi, there are several living witnesses who can prove or disprove whether somebody at some level on the Reagan team was negotiating with Iranian middlemen.

We must make sure that if a secret deal with a foreign power was pursued to win the 1980 election it never happens again. (Lloyd Cutler NYT op-ed May 15, 1991)

Emanuele Ottolenghi provided a thorough review of Sick’s conspiracy theory and thoroughly debunked it in his Middle East Forum article Gary Sick, Discredited but Honored. He wrote,

With the United States still reeling from the Iran-Contra affair, Sick’s accusations triggered a string of devastating journalistic critiques and two congressional inquiries that that definitively discredited the October Surprise conspiracy theory.

Ottolenghi established that Sick’s theory rested on the testimony of an imaginary figure, Mehdi Kashani. But despite the unraveling of the charges, Sick paid no price for perpetrating the fraud. Sick remained a go-to expert at CNN and C-Span.

My more detailed story of collusion begins in 1921. The 20s were marked by a cultural revolution, the Roaring 20s, and politicians’ desire to reconstitute the shattered world order that was left in the wake of WW I. While post-war World War I Republicans are painted as isolationist, the isolationist impulse didn’t gain dominance in the party until the 1930s. Although a Republican senate had rejected U.S. participation in the League of Nations, the Harding administration sought to reassure America and the world that it was committed to Wilsonian principles. Then as now, the U.S. assumed that diplomatic agreements were not the exclusive business of one organization like the League of Nations, and tried a different tack.

With that goal in mind, the United States hosted the Washington Conference in 1921. It convened, dramatically, the day after the Tomb of The Unknown was dedicated on Armistice Day 1921. The confreres were there to address naval disarmament and China’s financial and political instability.

After President Harding welcomed the participants, Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, without prior consultation, followed with a proposal that stunned all those present at the opening session of the conference. He called on the naval powers to scrap sixty-six battle ships either built or under construction. The end product of the negotiations was the Washington Naval Treaty, best known for the 5:5:3 ratio of battleship tonnage accepted by the British, Americans, and the Japanese.

A belief that a naval arms race precipitated the war had become axiomatic, so if you could limit the size of navies you could avoid another world war. The talks were successful, battleship building was limited, and all seemed to be going along swimmingly until six years down line the United States discovered that their main naval rivals, Britain and Japan, diverted their resources from building battleships into building cruisers, a class of ship omitted from the treaty. The cruiser was, in terms of weight and fighting lethality, just below the battleship.

Avoiding a new arms race seemed simple enough to the Americans. If you could just bring cruisers under the same limits that were agreed to for battleships at the Washington Conference the balance would be restored. And so the Geneva Naval Disarmament Conference, also known as the “Coolidge Conference,” convened in June of 1927, with the purpose of addressing the cruiser issue.

The British and the Americans could not agree on the weight limits for these ships, the size of their guns, nor the number of ships allowable. That was because they had very different strategic requirements.

The British had numerous possessions and bases in the Pacific, thus a larger ship with longer cruising range wasn’t a requirement. They preferred smaller but more numerous cruisers. The United States holdings in the Pacific were spread out over vast distances and, in order to project power, they required a larger cruiser with a greater cruising range.

The Japanese were still feeling the effects of the great 1923 Kanto earthquake that had leveled Tokyo and the bank panic of 1927. They seemed amenable to a limitation agreement. At this brief moment in history, those Japanese in favor of limiting arms held sway, and the Japanese delegates attempted to ameliorate Anglo-American differences. Nothing finally was accomplished, as U.S.-British relations reached their nadir.

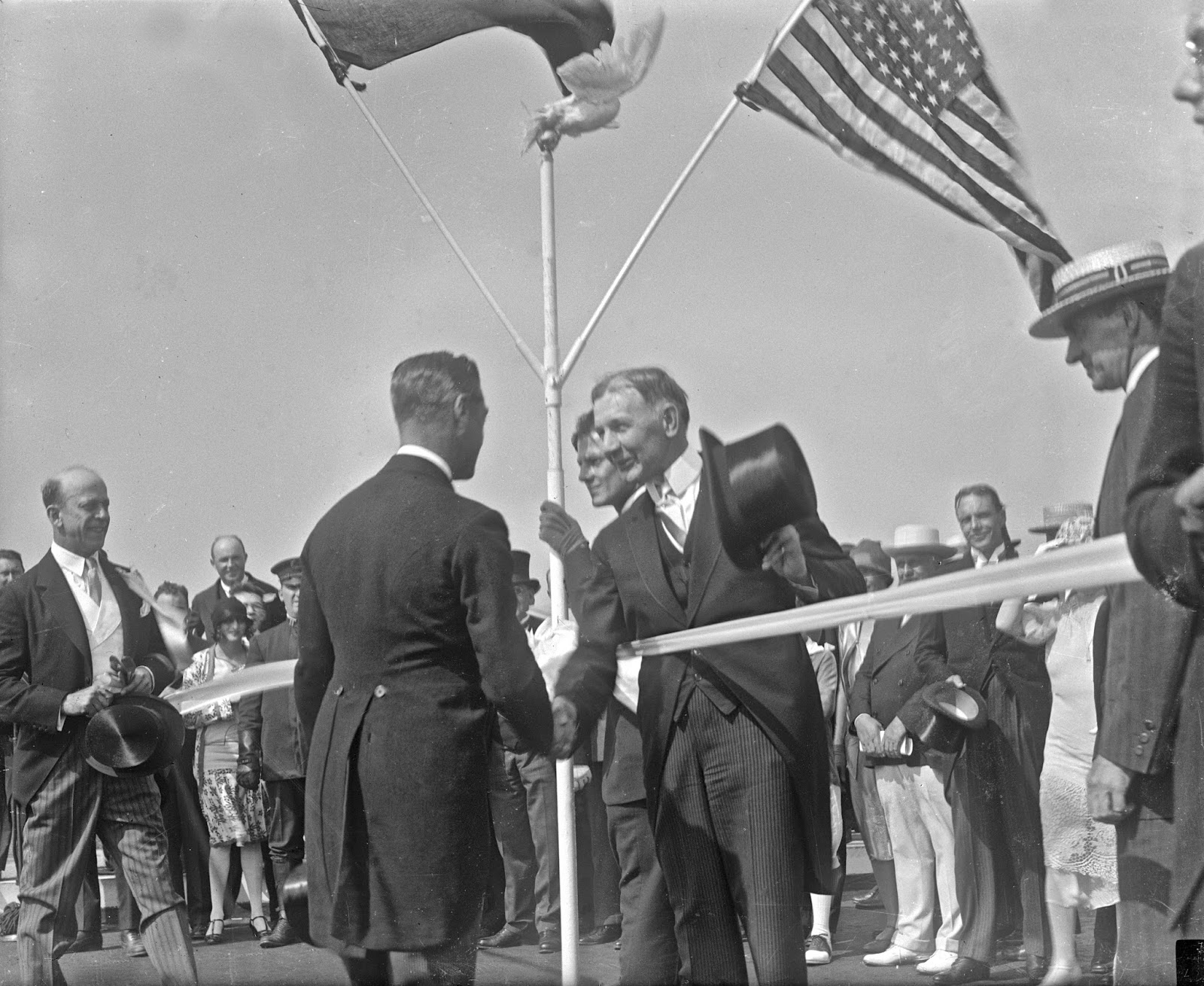

Once the conference collapsed, the most curious and interesting aspect of the post-mortem was the acrimony and finger pointing back home in America. On August 7, Vice President Dawes speaking at the gala opening of the Peace Bridge in Buffalo, connecting Canada with the U.S., shocked the dignitaries that included the Edward, Prince of Wales, the arbiter of style, Britain’s Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, and Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg. In his remarks, Dawes accused his own State Department of a lack of preparation prior to the conference: America was to blame for the conference failure.

Once the conference collapsed, the most curious and interesting aspect of the post-mortem was the acrimony and finger pointing back home in America. On August 7, Vice President Dawes speaking at the gala opening of the Peace Bridge in Buffalo, connecting Canada with the U.S., shocked the dignitaries that included the Edward, Prince of Wales, the arbiter of style, Britain’s Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, and Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg. In his remarks, Dawes accused his own State Department of a lack of preparation prior to the conference: America was to blame for the conference failure.

While Kellogg betrayed no emotion publicly, he exploded privately. Dawes had no role in the negotiations; he was out of the loop, to use the current phrase. But Dawes did have presidential ambitions, and his speech came just five days after Calvin Coolidge uttered his famous declaration “I do not choose to run for President in 1928”.

Over the next two days front page stories and editorials in the New York Times would endorse Dawes’ views.

. . . Perhaps, before this conference was held, there was not a careful preliminary appraisal by each conferee of the necessities of the other. Perhaps, exclusive concentration by each conferee on its own requirements resulted in a predetermined ultimatum before a comparison of views. Perhaps the public announcement of respective programs early in the conference produced fears of domestic public repercussion if they were reasonably modified, as would be necessary to affect an agreement.”(New York Times, August 8, 1927)

Kellogg was perplexed. The same people who claimed he had failed to properly prepare for the talks applauded Charles Evans Hughes seven years earlier for his surprise proposal that lacked any prior discussion!

In fact, the months leading up to the Geneva Conference were marked by constant diplomatic sessions in which the positions of the respective countries were made known. The United States had also attended the League of Nation’s Preparatory Commission on Disarmament in Geneva.

Kellogg had even attempted to enlist former Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes to represent the U.S. at the Geneva Conference but Coolidge recommended that talks be carried out with little fanfare “in the normal businesslike way, refraining from any effort to produce an artificial impression by the selection of outstanding personalities.” Dawes was guilty of spreading “fake news.”

Dawes was not the only member of the Coolidge administration interested in the White House who was willing to jump into this foreign policy briar patch. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, a Quaker, a committed Anglophile, and a believer in disarmament, was horrified at the breakdown in Anglo-American relations. He was not averse to intervening in areas outside his responsibility or expertise. President Coolidge derisively referred to him as “Wonder Boy.” Coolidge famously said, “That man, has offered me unsolicited advice every day for six years, all of it bad.”

Hoover opened a backdoor channel with the British ambassador to Washington, and discussed the possibility of a joint American-British peace propaganda campaign on two occasions, but the idea made the British Foreign Office nervous, and it was quietly dropped. One might describe this as a clear case of collusion.

Hoover’s scheme would go nowhere. The specifics of his back-channel machinations were relegated to the footnotes. The time wasn’t quite right for Hoover, a Secretary of Commerce, to tackle foreign affairs. But that would change when he succeeded Coolidge and would whip up a collusion charge of his own and level it against the “Big Navy” lobby to advance his own disarmament goals.

One of Hoover’s first orders of business after his inauguration was to hammer out a new formula for naval disarmament. He summoned his personal friend Hugh Gibson, the American representative to the failed Coolidge Conference to the White House the first week after his inauguration. Gibson actually moved into the White House where he crafted the new American position.

The election of socialist Ramsey MacDonald as British Prime Minister in June of 1929 brightened the prospects of an Anglo-American rapprochement considerably. Hoover and MacDonald not only endorsed the Kellogg-Briand Pact outlawing war on July 24, they also announced the suspension of naval construction which effectively put an end to the cruiser construction bill designed to catch up with the British and Japanese.

The election of socialist Ramsey MacDonald as British Prime Minister in June of 1929 brightened the prospects of an Anglo-American rapprochement considerably. Hoover and MacDonald not only endorsed the Kellogg-Briand Pact outlawing war on July 24, they also announced the suspension of naval construction which effectively put an end to the cruiser construction bill designed to catch up with the British and Japanese.

Charges that a runaway pacifist now occupied the White House filled the air. Hoover’s critics gained traction. They included members of congress and patriotic societies like the American Legion. But Hoover got lucky when William B. Shearer, a paid lobbyist for the “Big Three” U.S. shipbuilding companies (Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, Bethlehem Shipbuilding, New York Shipbuilding Co.) instituted a lawsuit against his former employers claiming back pay of $257,655 ($3.6 million in today’s dollars) for wrecking the Geneva Conference in 1927. News of the lawsuit came to the attention of the State Department and was passed on to the White House.

Shearer’s success at self-promotion would prove to be his undoing. After the Hearst papers published Shearer’s expose of the Geneva Conference (The Inside Story of Intrigue at Geneva), Secretary of State Kellogg contacted Charles M. Schwab, president of the Bethlehem Ship Building Company regarding Shearer’s activities. That was enough to make Shearer a liability and all connections with him were severed.

Shearer is in many respects the prototype of today’s Washington lobbyist with a few critical differences. He was a true believer in his cause, the maintenance of a modern powerful navy, and he operated in the limelight instead of the shadows. Shearer maintained close relations with the New York Times and Chicago Tribune, and that friendship provided him with publicity and press credentials when needed. In return Shearer provided a steady stream of inside information. (The most comprehensive study of the Shearer affair can be found in The Shearer Scandal and Its Origins by Joseph Hugh Kitchens Jr., Ph.D. dissertation 1968, University of Georgia)

.JPG)

For Hoover, it was a golden opportunity to attack “Big Navy” advocates. A new twist had been added to the arms race argument. It was a paradigm created out of the literature and poetry of W.W. I that captured the horrors of mass warfare so eloquently, along with a clever post-war German manipulation of their archives that made it appear that everyone was equally to blame for the war, rather than unbridled German imperial aims. It wasn’t German aggression, but the merchants of the death, the arms manufacturers, who had to be brought to heel.

Unfortunately, statesmen and historians were all too willing to accept these premises uncritically. This, then, formed the zeitgeist for the interwar disarmament negotiations that still hangs over us today.

At a press conference, Hoover called on the shipbuilding firms named by Shearer to disprove the charges against them. At Hoover’s urging, Shearer’s activities became the subject of a Senate investigation that captured the headlines and, consequently, the public’s attention.

Simply put, the Coolidge Conference failed, according to contemporary critics, because low minds or incompetent diplomats or something equally venal, the collusion of shipbuilding firms and the “Big Navy” lobby made it fail.

The idea that failure might be the result of something more intractable, that there might be for example, such a thing as the “national interest” seen differently by different nations, and that those interests might conflict with a supra-national notion of disarmament was simply unacceptable. Therefore failure had to be the fault of either the colluders or the provincial Coolidge who cared little for international affairs.

Henry Stimson, Hoover’s Secretary of State, thoroughly accepted the view voiced by Lord Grey, British Foreign Secretary from 1905-1916, that “. . . Great armaments lead inevitably to war. If there are armaments on one side there must be armaments on the other . . .” When informed that the State Department had successfully decrypted the diplomatic cables sent from Europe and Japan to the Washington Conference, he declined the offer to attempt to access the same information at the London Conference famously stating, “gentlemen don’t read other gentlemen’s mail.” Of course Stimson in his second go round as Secretary of War under FDR, had the opportunity to modify his views. Rest assured that he was reading the mail on December 7, 1941. By then however, it was too late.

Then as is now, there is a predisposition to attribute nefarious intent—collusion, to political opponents in the face of undesired outcomes. It has always been thus, but the current Russian collusion narrative represents a qualitative change.

An elephantine congressional inquiry mostly hobbled by the Democrat’s opposition along with institutional resistance to congressional subpoenas, has revealed a conspiratorial relationship between the Clinton campaign, the national security apparatus, and willing members of the media in the creation of the Trump collusion narrative. The congressional investigation mostly guided by a dogged Devin Nunes, has revealed that this iron triangle colluded to simultaneously cover-up their complicity in advancing the Russia-Trump conspiracy while crippling the Trump presidency.

To date, no indictments, arrests, or trials regarding the participants in this scheme have been brought. The handful of resignations and firings have in no way deterred Robert Mueller from acting on the allegations brought against the Trump campaign, nor has it elicited the slightest sign of introspection on his part that would indicate that he is aware that he has been snookered.

Should the criminal activities of the Clinton campaign team, FUSION GPS, the FBI, and the Department of Justice remain unresolved, a Rubicon will have been crossed. It will signal that this new paradigm for acceptable political opposition has become part of our political landscape and is certain to be repeated.

______________________________

Marc Epstein is the author of ‘The Historians and the Geneva Naval Conference’ in Arms Limitation And Disarmament: Restraints On War, 1899-1939, edited B.J.C. McKercher, Praeger 1992. He has a PhD in Japanese diplomatic history, specializing in naval disarmament in the interwar years. His articles have appeared in Education Next, The American Educator, City Journal, the Washington Post, New York Post, and New York Sun.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast