by Robert Lewis (April 2021)

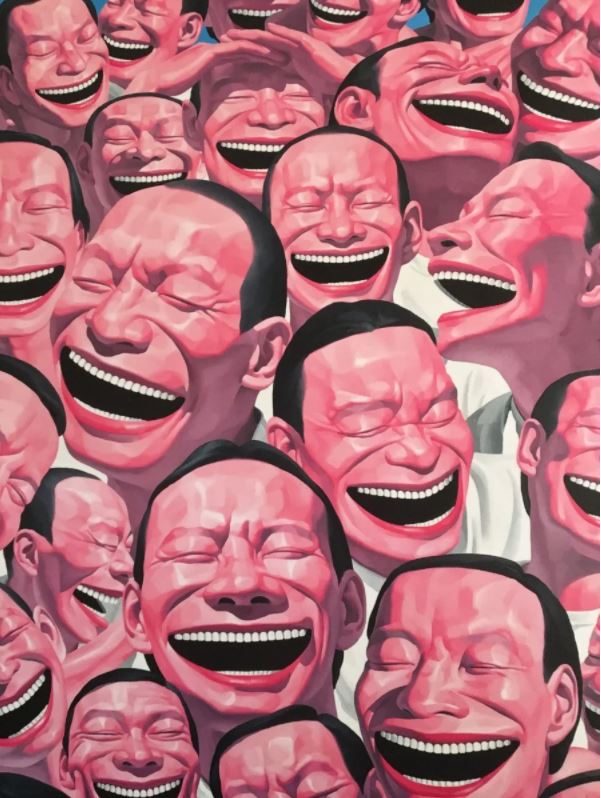

Garbage Hill, Yue Minjun, 2003

Laughter is the shortest distance between two people.—Yacov Smirnoff

The duty of comedy is to correct men by amusing them.—Moliere

Laughing feels good. The opposite of laughing is crying. No one wants to cry. Everyone wants to laugh. We are a species wired to laugh, to want to feel good. Keeping ourselves alive feels good (eating, quenching thirst), sex feels good, succeeding in life feels good.

Feeling good from laughter releases endorphins, boosts the immune system. The slave who could laugh in the face of despair, who learned to live and keep himself wholly in the present indicative survived—and procreated. It was his gift. Woe to the man who cannot partake of the “the laughter of the gods.”

Natural selection likes the funny guy, and all those he makes laugh. In moderation, wanting to feel good is a healthy impulse. But we all know, if only anecdotally, that wanting to feel good has gotten too many into big trouble. We spend hundreds of millions of dollars—sometimes at the expense of the necessities of life (food, rent, our children) —in pursuit of feeling good. When feeling good becomes its own terminus, it turns negative, destructive. With the blessings of nature, feeling good is meant to be the means to the end of optimal health.

Feeling good is an outcome that seamlessly integrates material and psychological well-being: you can’t have one without the other, a fundamental truth that certain cultures have grasped better than others. All the having in the world cannot relieve the wholly unnatural and unhappy state of being alone in the world. Loneliness, stress, low self-esteem are all inimical to well-being. The deeper the unhappiness deficit, the need to feel good intensifies and disproportionately preoccupies our time and capital. Las Vegas, whose mega-casinos offer mother-lodes of thrills and pleasures—from gambling, to circus acts, main event boxing, live music and stand-up comedy—is where the haves go to confess that something isn’t quite alright, and are convinced “the unexamined life” is the cure.

Should the success or state of the nation be measured by its GDP or the time and capital spent feeling good? As a percentage of GDP, we are spending more and more on drugs and alcohol compared to 100 years ago, and that doesn’t include the vast sums that have been spent on the laughable (losing) war on drugs. We’re also spending a lot more on comedy, gathering around the comic instead of the primeval fire. As a nation, we have been very inventive in creating diversions that cater to our growing need to feel good. Our collective, no-class-left-behind obsession with feeling good is the nation’s declaration that not all is as well as its material wealth would have us believe.

Among the surest and quickest ways to feel good is through laughter. Flick on the TV and there are any number of specialty channels dedicated to keep us laughing 24/7. Old comedy shows from the 1960s and 1970s are in vogue. And for a more intense and communal experience there are comedy clubs everywhere featuring over the course of an evening a parade of comedians. The circus that used to travel from one town to the next has been replaced by the comedy circuit, as more and more of us are willing to pay a pretty penny for a laugh.

What does the increasing demand for and proliferation of comedy tell us about our basic needs and collective values? Since laughing feels good and ranks high among the past times we default to in our fugitive quest for well-being, are there reasonable grounds to compare the laughing addict, someone who spends a disproportionate part of his day tuned into comedy, to the druggie who has to free-base cocaine all day long to get from one day to the next?

Laughter is a potent drug because it engages both the mind and body. Once you’ve understood the joke, the body is handsomely rewarded. From the Encyclopedia Britannica describing laugher:

Fifteen facial muscles contract and stimulation of the zygomatic major muscle (the main lifting mechanism of your upper lip) occurs. Meanwhile, the respiratory system is upset by the epiglottis half-closing the larynx, so that air intake occurs irregularly, making you gasp. In extreme circumstances, the tear ducts are activated, so that while the mouth is opening and closing and the struggle for oxygen intake continues, the face becomes moist and often red (or purple). The noises that usually accompany this bizarre behaviour range from sedate giggles to boisterous guffaws.

As to the origins of laughter, ethologists report that some of the higher apes are capable of laughter (doubtlessly because they couldn’t foresee what they would become) and the first Homo sapiens were endowed with the capacity to laugh.

For most of our history, we were responsible for our own laughter; it was created spontaneously as it was needed. Scripting and scheduling laughter is a very recent phenomenon, the first effect of a growing and unprecedented deficit in psychological and social well-being. If in the past we needed less laughter in our lives, what has changed between then and now?

It is as self-evident as the clown “who was only your fool for a while” that the conditions of life are such that we are unable to supply our basic laughter needs, or we are less capable of producing laugher because we don’t have enough time and/or the mind has been dulled by an over-reliance on technology doing the things we used to do. Either way, we now look to and depend on laughter specialists to supply our needs.

Despite the spectacular wealth generated by human ingenuity, ‘having’ doesn’t necessarily translate into psychological or spiritual having, which means the haves still haven’t grasped what constitutes real as opposed to apparent happiness. We’ve been sold hook-line-and-sinker on the consumer construct of happiness, and to such an extent that even comedy is now regarded as another item on a purchase list (God forbid bucket list). However, our unhappiness persists, despite the best laid plans of the buy-now pay-later template and being born into the exponentials of plenty.

Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor coined the term “the malaise of modernity,” a condition which I propose is significantly related to our alienation, our voluntary expulsion from the tribe or community? We are no longer a united people, but a nation of exiliacs for whom Facebook has become the living room of choice. For the first time ever, more than 50% of Canadian adults live alone. Is there a relationship between living alone and our pre-occupation with pets (petophilia) and our quasi addiction to comedy?

“When two people are laughing it is certain misfortune has befallen a third,” says the saw. But what if there isn’t a second and third person? Without the other, the joke’s on who? It’s on you. Small wonder television comedy dominates prime time television. And if that’s not enough, most mid-sized cities now feature a comedy club or two, and many of our largest cities program lengthy comedy festivals into their rites of summer. If you’re looking for a restorative, shared communal experience, there’s no better place than the comedy club to drop anchor.

From the court jester to the present-day comedian, the conditions of life have been such that there has always been a need for laughter, but it would take two centuries (from the Industrial Revolution to the 1960s), and a growing unhappiness (laughter) deficit for an increasingly unhappy population to finally begin to question the bloated claims of materialism. The counter culture or hippie movement proposed an alternative set of values. Riding a drug-fueled wave of euphoria and idealism, the hippies took their chances on the trifecta of “turn on, tune in, drop out.” Many of them, following the sitar drones of George Harrison to their ghatly source, looked to the East to fulfill their spiritual needs. But alas, Zen and the Upanishads didn’t pay the rent and the movement was eventually compromised by human nature—temporarily down but never out. We soberly note that Envy, Pride and Avarice have survived the hundreds of ‘isms’ that have been devised to disable them.

As the hippie movement—a fatuous last stand against the juggernaut of corporatism—petered out, the demand for comedy dramatically increased and continues unabated. But it is for more than ‘just for laughs’ that many of us are dedicating increasingly larger segments of our day to comedy. Our freedoms, especially First Amendment freedoms are under siege, in part because the Tsars of political correctness (PC) enjoy popular support at the ballot box. Never before have we been so hamstrung by PC. You can’t open your mouth without offending someone; and if you argue against victims’ rights, you’re either a racist, homophobe, or sexist. The comedy club is the only public place where PC hasn’t made any inroads. In the club, nothing is sacred, no joke too offensive or dirty; it is where the people in their marvelous diversity come to air out their hang-ups and civilizational discontents with a grin-and-bear-it as wide as the world, and the only thing hurting are them bellies full of laughter, and the only angry man is the guy who can’t get a ticket.

Laughter (comedy) is healing, it is therapeutic; it allows us to reconnect with our authentic, essential selves. In its funny way, it fills a void in our spiritual life that left unfulfilled leaves us vulnerable to an endless procession of quick fixes and their dubious claims. And finally, laughter allows us to indulge human nature so we can more easily recognize it to better understand and manage it.

Suffice to say the increasing demand for laughter in our lives is no laughing matter.

If you’ve made it to the end of this essay, you deserve a laugh. Arthur Koestler, from The Act of Creation, explains that all humour derives from the “bisociation of unlike matrices.”

__________________________________

Robert Lewis was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He has been publislhed in The Spectator. He is also a guitarist who composes in the Alt-Classical style. You can listen here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast