by Guido Mina di Sospiro (January 2024)

I have been promising myself for a couple of years to write a piece for NER entitled Poor Arts, Orphans of the Aristocracy. In it, I would explain summarily—as it would be an essay, not a book—why it is that just about all of the greatest works of art in the history of western culture were accomplished thanks to a warm relationship between the artist and his patron. Indeed, patrons were not just fund-giving but otherwise irrelevant persons: often they were deeply learned connoisseurs who might have been significant artists in their own right had they not had a country, or a church, or an army to run. For example, Archduke Rudolf of Austria (who was consecrated as Archbishop of Olomouc in 1819, and then cardinal in the same year, and therefore had quite a bit of business to attend to) was not only one of Beethoven’s patrons, but his best student, the only one to whom he taught composition. When Beethoven composed the Emperor Concerto, and dedicated it to the Archduke, the latter performed it for the first time in private (on 13 January 1811 at the Palace of Prince Joseph Lobkowitz in Vienna; later, on 28 November 1811, it was performed in public at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig under conductor Johann Philipp Christian Schulz, with pianist Friedrich Schneider as the soloist); which means, Archduke Rudolph could play competently the piano part, which at the time, in 1809, was the very pinnacle of pianistic virtuosity.

Of course, centuries of relentless propaganda against the aristocracy, not to mention assorted genocides, have persuaded most people that aristocrats were evil and at best useless parasites—though their artistic legacy is before the eyes of the world. All it takes is to walk around Rome, or Venice, or Prague, and so on and on. The Aristocratic Age is long gone and we live in the Age of the Philistines. Immensely wealthy individuals today—Gates, Bezos, Soros and the like—prefer to play at Dr. No. They have no notion of or interest in the arts. Their appreciation of culture is that of a Paleolithic man, or in fact less, since some unknown Paleolithic artists produced vast panoplies of pictographs and petroglyphs in caves that we marvel at today.

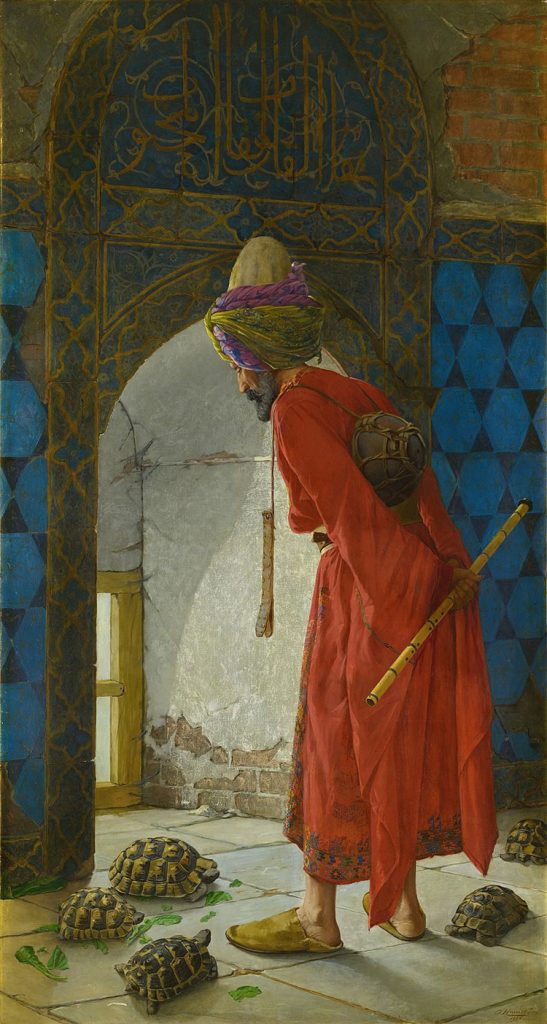

But is commissioning art still possible in 2023, especially without deep pockets? Last year I wrote Of Painters, Impostors, and an Artistic New Wave from Latin America, describing a new crop of extremely talented, figurative/surreal painters all hailing from the Cono Sur of South America, and that is Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. Back in September, I found myself in Istanbul, or, as I prefer to call it, Constantinople. I had read on some guide that I must absolutely see the Mona Lisa of Turkey, and that is, The Tortoise Trainer or Tamer (in Turkish: Kaplumbağa Terbiyecisi), a painting by the polymath Osman Hamdi Bey (1842 – 1910), who was an Ottoman administrator, thinker, connoisseur of the arts and also a remarkable painter who as a young man spent nine years in Paris where he became influenced by the art scene. He was also an archaeologist and the founder of Istanbul Archaeology Museums and of the Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts. So much for past glories: the Pera Museum, where the painting is exhibited, was deserted. “Great,” I thought, as I lingered in front of it in all of its splendor:

One should wonder, “How do you train tortoises?” Indeed, the title in Spanish is even more comical: El domador de tortugas, i.e., the tamer of tortoises. The painter meant to satirize the late and ultimately ineffective attempts to reform the Ottoman Empire. To my eyes, it’s an ode to strangeness: a Sufi is intent on “taming” (?) a bunch of tortoises who seem more interested in eating salad. Above them all the inscription: Şifa’al-kulûp lika’al Mahbub, “The healing of the hearts is meeting with the beloved”. There is, furthermore, the expression “turtles all the way down”, which brings into play the concept of infinite regress.

The painting stayed with me and a few weeks later, from Italy, I sent the painting’s photo and a message to the Chilean painter Lobsang Durney, in Valparaiso. “We would like your take on the same subject: the tortoise tamer, with the old Sufi who tries to tame the tortoises, though they seem to prefer to eat salad … With your sense of humor.”

His reply came a couple of days later: “Perfect! Yes, and I would make the tortoises bigger and juggling, and the tamer playing an instrument. I would leave the background the same because it gives a very good context. I would only modify the view out of the window by adding a surrealistic landscape. And I would keep the tonalities and the light, which are great.”

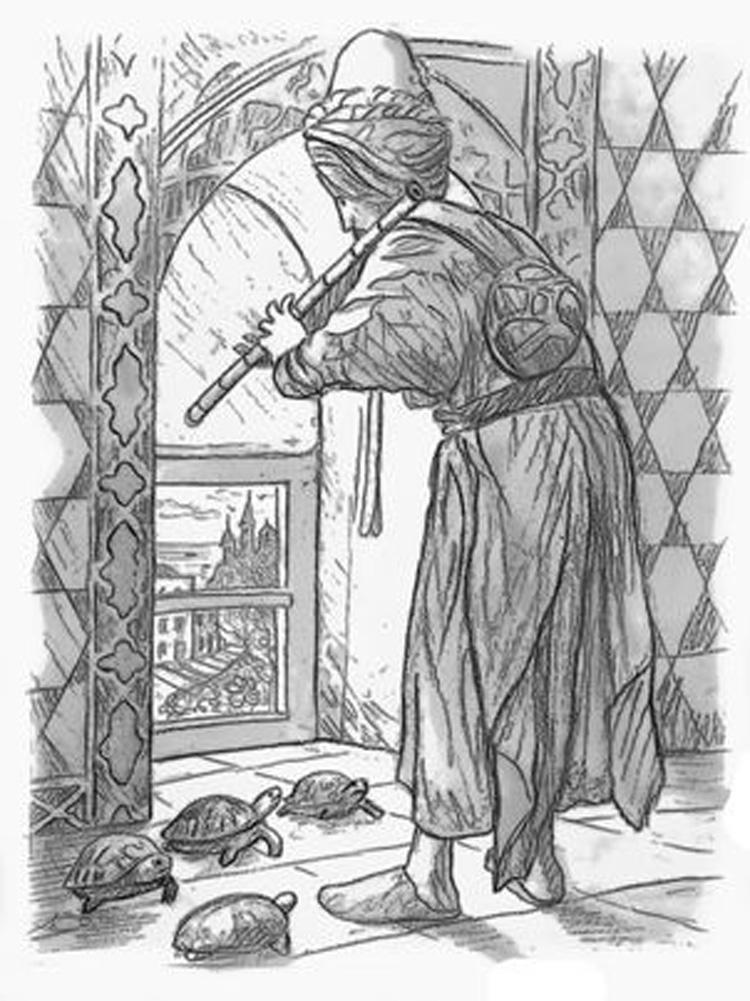

We agreed on a price and I gave him the go ahead. He would first be sending me a sketch. Which he did, a couple of weeks later:

I consulted my wife and then replied: “Your drawing is, as always, technically very accomplished, but I suspect that, out of respect for the original, your version of it is little more than an homage.

“Maybe you are not inspired to crowd it, as you did in the Eiffel Tower painting among many other works of yours, with various strange objects and animals animating the painting; or placing your characteristic Valparaiso-inspired cityscapes; or something drastically surreal, like UFOs landing on the other side of the window while both the tamer and the tortoises are wasting time with each other and don’t even notice…

“I’m not urging you to change the painting according to my expectations, which are based on your usual stylistic approach; I’m simply saying that I was hoping for something more along those lines. Don’t worry, there will be other paintings of yours that will find their way into our home as did their various predecessors…”

His reply came a few days later: “Thanks Guido for all your comments, which are always welcome, this way I think one can achieve good results by taking ideas from different sources, and I think it can be done, as painting supports everything and we can make everything happen in it. If you want I can draw another sketch, no problem, I like to draw, just to see those more playful possibilities reflected in this pictorial tribute, it would be a pleasure. I liked the aliens 👽.”

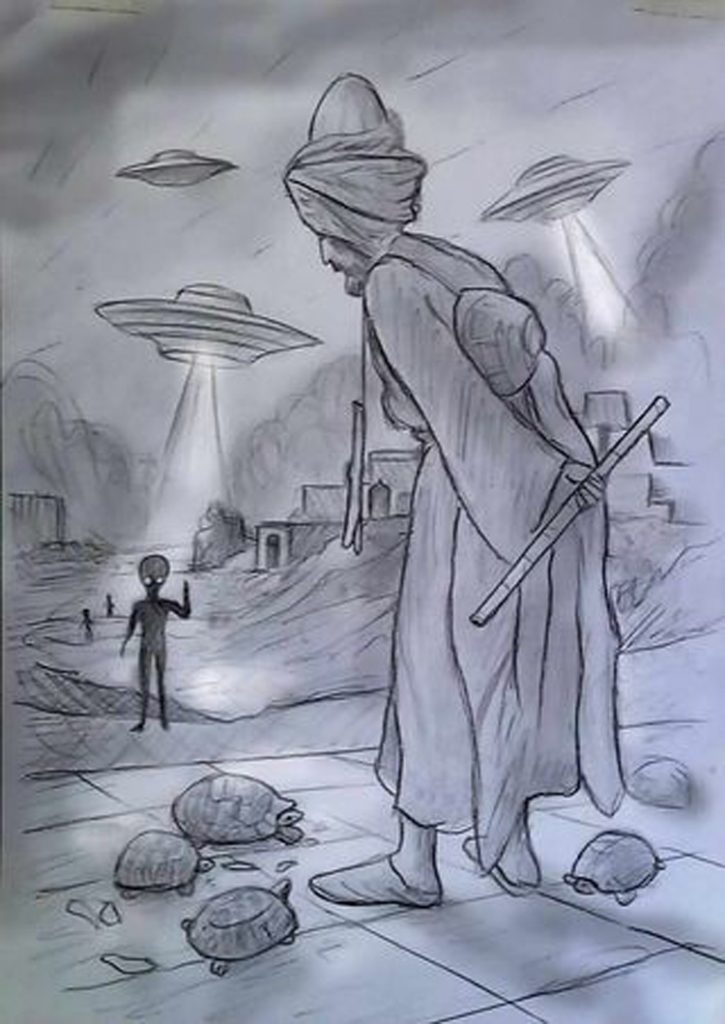

The idea of the aliens was a brainwave by my wife. It had not occurred to me, or to Lobsang. We told him to go ahead, and he came back with the following sketch:

And added: “Action-packed alien invasion in an Arabian desert landscape in front of an indifferent tortoise tamer.”

It did not take us long to respond: “Great, we like it very much! 100×80 cm (40×32 inches)? We can already imagine your bright colors. It would be nice to write below: ‘A metahistorical homage to The Tortoise Tamer by Osman Hamdi Bey’.”

The sketch may not look as promising to your eyes as it did to ours because we are thoroughly familiar with Lobsang’s work, own a some of his paintings, and know that he is brilliant.

Two or three weeks went by, and in the meantime we made our way back to the States. Then, one evening, I received the following e-mail from Lobsang:

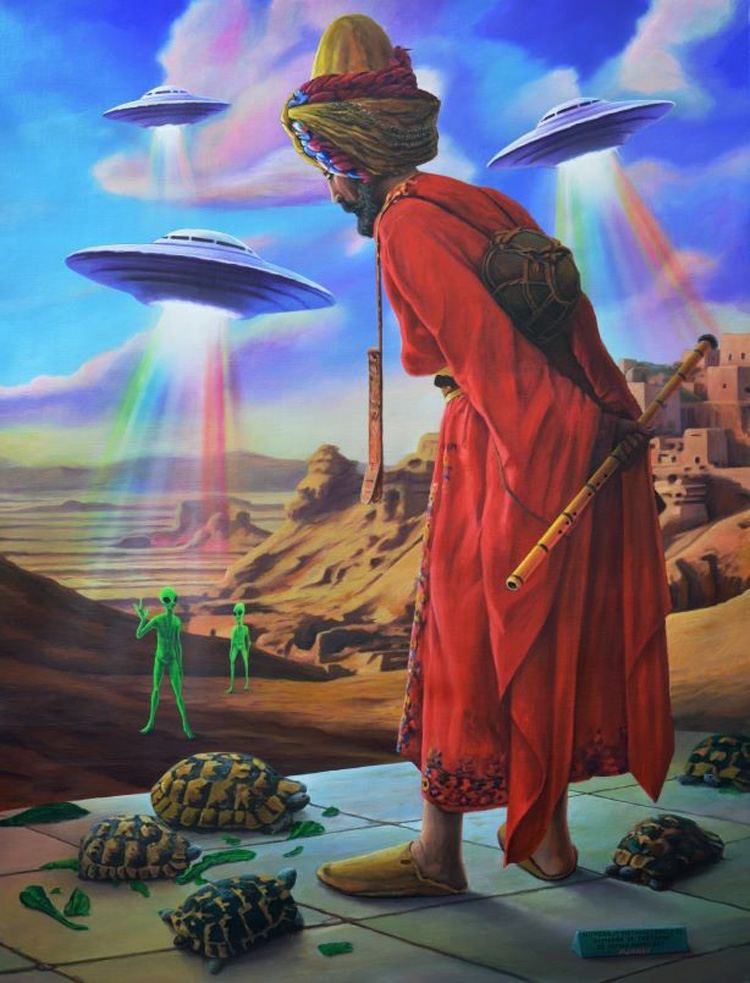

“Hello, Guido, I hope you are very well. Attached is a high resolution image of the tribute to the tortoise tamer (Homenaje meta-histórico al domador de tortugas). Let me know and we’ll keep in touch.”

We thought it was impressive (with the aliens the same green as the salad!), and told him as much. He wrote back to say, “Thank you very much, Guido and Stenie, it’s always a pleasure to have you like my work; I put a lot of effort into it.”

And there it is: I suppose a patron, so to speak, can still commission a painting from an artist, and can give him a few ideas about its execution. I hope more and more people will have a chance to do as much.

Table of Contents

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, and Forbidden Fruits.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link