By Guido Mina di Sospiro (November 2018)

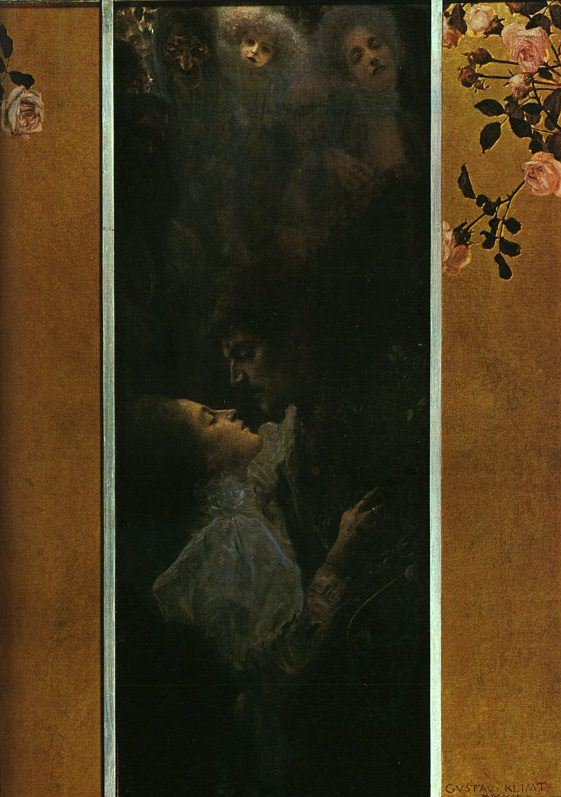

Love, Gustav Klimt, 1895

From 1833 to 1838 French composer Hector Berlioz wrote what cumulatively became known as A Critical Study of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies, thus becoming Beethoven’s greatest champion in France. While the musicological insights are noteworthy, the style is so florid and passionate that, to our contemporary sensibilities, it comes off as over the top. As I am equally enthusiastic about Beethoven’s Emperor concert, I thought I would write a piece about it in the style of Berlioz. Though such an approach may reek of post-modernism, my passion is sincere. Just prepare yourself to read something straight out of the Romantic Age.

Musicologists maintain that, in the history of classical music, the symphony and the sonata are the more ambitious form of composition. In effect, the concerto for one or more instruments and orchestra is inevitably more theatrical, often promoting, rather than music per se, vacuous virtuosity. But Beethoven’s “Emperor” concerto for piano and orchestra elevates the generally facile juxtaposition between soloist and orchestra to an accomplished integration of Animus and Anima, sun and moon, the two opposing elements of the universe in a triumphantly réussi instance of coniunctio oppositorum.

The following should encourage readers to go back to the source, i.e., the concerto itself, whether it be the first time they listen to it, or the umpteenth.

Beethoven’s Klavierkonzert No. 5 [Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major Op. 73 (“Emperor”)] is the prototype of concerting perfection. The orchestra being the woman; the piano, the man; their music together, lovemaking.

What does concert mean anyway? From Italian concerto, from Old Italian, agreement, harmony, possibly from Late Latin concertus, past participle of con-cernere, to mingle together. Later attempts of less gifted composers pale in comparison; some are actually laughable, especially Tchaikovsky’s first, swashbuckling but histrionic and hollow. The solo instrument struggling against the orchestra; the orchestra trying to drown the soloist in jumbled fortissimi. Male and female at odds with one another, brawling in public!

To return to the Emperor.

I. Allegro

The first movement is what enfeebled men to come—modernists, existentialists—could never have conceived of, let alone composed. The orchestra introduces the piano abruptly: a loud, fortissimo tutti, just a few seconds and then—à toi, mon amour, she, the orchestra, seems to imply. And the piano obliges her with fantastic arpeggi and scale-figures, cascading scintillatingly in a dazzling, cadenza-like display of virtuosity, but not end in itself. He, the piano, is doing this for his lover, the orchestra. Hoping to impress her, there is nothing like flamboyance to do so. Her punctuating fortissimi seem to confirm that he is pleasing her. Then, the fireworks are over and the two settle down to business.

Undeniably impressed by his courtship and by the degree of preparation that’s clearly gone into it, she accepts his overtures. The theme is introduced. And then, what is it? It is unadulterated love.

The orchestra herself shows him that she doesn’t intend to be a passive receiver of his attentions. Her inspiration and her prowess are equal to his. And even as nimble, which is amazing, for she numbers fifty instruments or more. So she takes the lead, and the piano keeps quiet, respectfully and admiringly while, unheard by anyone, he gently weeps.

It is time to be united again. He ascends to her heights by ways of a vertiginous scale, which levels off with a sustained trill. He wishes he could sustain notes like an organ, but as soon as a note is struck, it starts waning. A trill is his expedient to sustain his notes indefinitely. But then no one better than he knows how to chisel symmetrically heavenly melodies out of the chopping chords of his hammers. Percussive or not, all he can do is sing.

Then the theme is played again, more gently this time. But before long, passion builds up again, and re-conquers the two. It’s another fortissimo, then a piano, while the tempo keeps changing—nothing will stop their emotions and dexterity. They play with abandonment, and yet restraint, careful not to overstep their respective bounds, knowing only too well that if that should happen, noise and pain would result, rather than music and love.

It is a challenge, but both challengers respect the self-imposed rules. And the wide-ranging enharmonic modulations; the key-scheme so respectfully revolutionary (by keeping the genie inside the bottle, by bending and stretching the rules but ultimately respecting them, Beethoven was more powerful than his contemporary Schubert, who instead did let the genie out of the bottle, and would modulate freely to distant tonalities); the chords hammered out from the deepest layers of the piano’s psyche, ready to leap forward, into full-blown romanticism.

But here the piano reverts his impetuous march, and recedes, astonishingly, to counterpoint. It is not time to leap yet. The orchestra returns peremptorily to either the dominant or tonic, in a bid not take it all too far, lest breakage should ensue, not rapture. The piano enters and departs the scene with chromatic scales, while the orchestra approves and plays on. Even the cadenza becomes redundant—the whole movement is awash in virtuosity, it is virtuosity. For the sake of love, this and more!

The Allegro ends in unison, forte, fortissimo, and then piano, oscillating widely in dynamics and emotions. “I’ve shown you all my pyrotechnics,” the piano announces, “could we now make love caressingly?”

The orchestra gives consent with three conclusive chords.

It’s time to repose.

II. Adagio un poco mosso

A lover’s strongest words are the ones whispered in his lover’s ears. It is the orchestra, her strings—should I say her hands?—who begin the caressing. A few reeds participate too. A brief suspension . . . and the piano must intervene.

Hesitantly melodic at first, and yet with the perfect deliberation of a god, he sings his tune in a celeste-like manner, what a contrast with his former flamboyant self! It’s but a few descending scales.

And we, who think of grace as rising, let

us

be

disconcerted

hearing it . . .

descend.

But he can’t resist the temptation of a few t(h)rills.

“Very well then,” declares the orchestra, “but do not exceed!”

Soon he resumes the melody, and she accompanies him with ladylike delicacy. Then it is he who accompanies, and she who sings, her flutes above her strings. Those are the ways of lovers. Adagio, but, un poco mosso . . .

The piano announces a change in direction, timidly, twice . . .

Then,

III. Rondò: Allegro ma non troppo

it’s a sudden explosion!

He and she intone an effulgently gyrating rondò, which reiterates the same emotion but in more vivid tones and faster tempo. Man and woman fully intoxicated by their syncopated, fast waltz, but never quite out of control, never trespassing into orgiastic chaos. On the contrary, their abandonment is conscious and unconscious at once. Gyrating, rotating, spinning, circling, orbiting—isn’t that what planets do in their annular pursuits of empyrean love?

From the dizzying speed and height of the Allegro, the piano slows down his race, and engages in a duo with the timpani, of all instruments! It’s the natural conclusion to so much giving and taking.

The two kiss for the last time, the way lovers kiss after their passion is placated. It is a moment of such musical as well as spiritual enormity, God partakes of it. If the history of mankind ended on those final notes, it wouldn’t be entirely unacceptable.

Lamentably, Beethoven finished the concerto with a bang, a final run-up. A clashing fortissimo of both piano and orchestra follows that moment of sublime divinity. Conventions of the time. It’s almost as if two lovers, after having made love, asked each other, “Did you like it?” and shouted their answer for the world to hear.

_______________________________

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, and The Metaphysics of Ping Pong.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link