by Brian Patrick Bolger (February 2024)

We stand now on the crepuscular twilight of another World War. The difference being that the west is ill-prepared for war. For conscription. On the eve of the Second World War, the liberal Guardian newspaper mocked the 400 million GBP demanded by Chamberlain to boost and modernise the army. The problem is the same today: the liberal world versed in the culture wars and progressive mantras of the 1990s is brainwashed into thinking that ‘someone else’ will look after us— ‘someone else’ being NATO. But more fundamentally, the left is inherently disloyal to the nation, evincing a globalised thinking which destroys the nation at home and any sense of community. The institutions of the UK, from universities to think tanks to the civil service, are inhabited by the trahison de clercs of modernity: intellectually sterile and with a sheepishness and wilful lack of resolve. They are ‘Ostrich people’ with an ignorance about the real nature of history. History does not progress in a linear way to liberal Netflix world. History is cyclical and is made by Napoleonic figures immune to ‘theories’ or ‘systems.’

One of the pervasive myths of the twentieth century is that of progressive thinking of the materialist visions of history. Thinkers such as Fukuyama took history as a type of Hegelian progression, an unfurling of ‘freedom’ or ‘progress’ to the ‘end of history,’ which they saw in the liberal democracy of the 1990s. There is in all types of materialism, from Liberalism to Marxism, a vision of accumulated enlightenment, a triumph of scientism over superstition. You just need a ‘system,’ a rational plan. In the 1990s, an entire repertoire of liberal thinkers in western universities believed that this had been reached through ‘globalisation’ (Anthony Giddens). For Hegel, history was the development of the consciousness of freedom. From the twisting dialectic of history there is a gradual opening of freedom from the absence of freedom in China, India and Persia to its flowering in the Reformation and Enlightenment. For Hegel, the Middle Ages represents a ‘long, eventful and terrible night,’ whilst the Renaissance is ‘that blush of dawn which after long storms first betokens the return of a bright and glorious day.’ The Renaissance harkens the ‘all -enlightening Sun’ of modernism. However, in his Philosophy of Right, Hegel asserted that ‘The Owl of Minerva only takes flight in the dusk’; which is that ‘Philosophy’ comes after History, after an epoch. We can look back at it, provide an analysis, but not the other way around. We cannot construct systems such as ‘liberal democracy’ or Marxism and implement policy in this dawning sunlight of the first day.

The nature of liberal thinking is that ‘space and time’ are reduced by technology; that the internet, travel—this cosmopolitanism and trade will lead to Kant’s ‘perpetual peace.’ Globalisation would break down cultural barriers. But democracy is decaying. Everywhere an authoritarian spectre casts a shadow over the morning sun. From the UK to China, liberal democracy is old hat. The necessity of technology, the needs of modern war strengthen executives at the expense of democracy. As with nineteenth century ‘liberalism,’ globalisation is used as a cloak to legitimate a universal narrative for the benefit of transnational capital. In opposition: the erosion of nation states is accompanied by the development of civilisational ‘grossraums’ (Carl Schmitt) such as China and Russia.

Inside the nation states of the west are huge groups of dissidents who have no loyalty to the community. These are embedded into institutions. From transgender think tanks to feminism, the leftist University fraternity, the main political parties of Europe are all attempting to build a brave new world as the border regions smoulder. There is a febrile lack of unity and community in the west, due to irresponsible immigration and a diminution of free speech. Endemic social problems from poverty to drugs means the west is unable to adequately face external threats. Britain, according to the defence secretary Grant Schapps, iterates that Britain is moving from a ‘post war to a pre-war world’ and warned that Russia is ‘about defeating our system and way of life.’ Sweden likewise is preparing for war with the defence minister Carl-Oskar Bohlin urging citizens to join a defence organisation.

Serbia is moving towards conscription as President Vucic warned that ‘without the army we would be trampled like a cockroach,’ although, considering Serbia is not a member of NATO, it is unsure where the threat lies, bearing in mind Serbians’ memories of the NATO bombing of Belgrade in the 90s. And there’s the rub. Likewise in Hungary, there is an ambivalence to which way the wind blows. Many east European states, although wanting independence, are also fearful of rousing the bear. Finland already has 80% military service.

Yet the generation of west European nations, brought up on a cocktail of sedentary lifestyles, an almost Jesuit-like indoctrination in schools, poor parenting and no memory of the cold war, are ill-equipped to face ‘realpolitik.’ The shrinking of time and space, through technology and the Internet, has meant a zeitgeist of ‘virtual worlds.’ Liberalism espouses a doctrine of ‘negative liberty’; a penchant of doing whatever one likes with no responsibilities to the Church, State, or Family. Atomised and pampered individuals of the west are unsuited to trenches and warfare. They are convinced of scientific, technological solutions to all problems. The leaders and elites do not know suffering. As was witnessed during Covid, suffering for the English middle classes is a lack of quinoa in Sainsburys. To change the thinking of a nation will only come later, after the war.

The Owl of Minerva will take flight after the wars, after the disaster of the twentieth century, after a few more million deaths. Perhaps then a wake up call, a realisation of the legacy of liberalism and its enriching of an elite transnational minority at the expense of ordinary people, of community. Like in the first and second world wars, it is those dreadful working class populists who will be asked upon again to fight for a nation in which they are demonised and ostracised. Yet would you really fight for Rishi Sunak and Sadiq Khan?

Table of Contents

Brian Patrick Bolger LSE, University of Liverpool. He has taught political philosophy and applied linguistics in Universities across Europe. His articles have appeared in the US, the UK, Italy, Canada and Germany in magazines such as The American Spectator, Asian Affairs, Salisbury Review, Deliberatio, L’Indro Quotidiano Indipendente di Geopolitica, The National Interest, GeoPolitical Monitor, Merion West, Voegelin View, The Montreal Review, The European Conservative, Visegrad Insight, The Hungarian Review, The Village, New English Review, The Daily Globe, American Thinker, The Internationalist, and Philosophy News. His latest book is Nowhere Fast: Democracy and Identity in the Twenty First Century (Ethics International Press).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

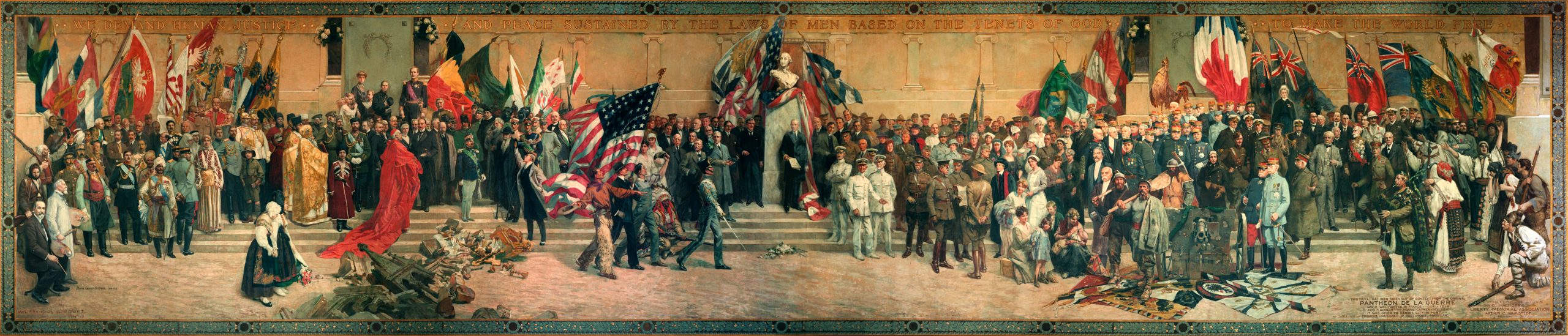

Thank you for the good essay. If anyone reading this visits Kansas City, Missouri, I recommend the National World War I Museum. The 402-foot mural is displayed in the original Museum building, which now is an annex to the much larger display. The mural is wonderful for anyone who has an interest in the Great War. I am a nurse and was pleased to see Nurse Edith Cavell included in the pantheon of important figures.

The situation in the US is somewhat like that of ancient Israel when the nation became too prosperous. Materialism and assuming that all is well, followed by disaster and deportation, is the pattern. Youth in the US have high levels of poor fitness, high levels of anxiety and depression, and many are not suitable for military service. Many are pretty totally ignorant of any reason to see their country as lovable and worth their sacrifice. We are in deep weeds.