by Jeffrey Burghauser (August 2024)

In the Introduction to his 1939 Autumn Journal, Louis MacNeice writes that he isn’t “attempting to offer what so many people now expect of poets—a final verdict or a balanced judgment.” Today, alas, we expect from poets neither a verdict (however final) nor a judgment (however balanced); indeed, we expect nothing beyond poor grooming, concupiscence, and bad politics. Poetry is nearly a dead language. Making a poem is too often understood as a purely symbolic gesture. It’s like a translation of Das Kapital into Klingon: a backbreaking attempt to seduce an almost non-existent audience. A contemporary poem is self-aware, as it must be; after all, nobody else is going to be aware of it.

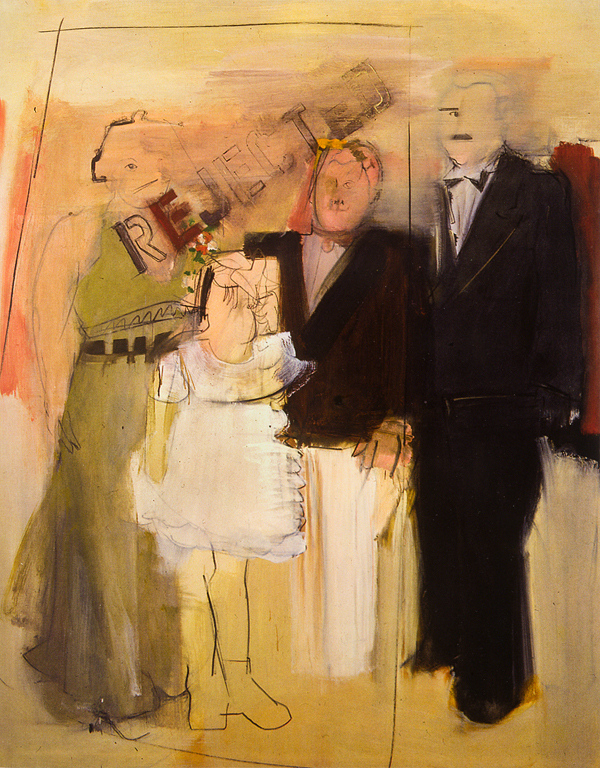

Redemptive glimmers exist, however; and amid our generalized anxiety and hopelessness, any glimmer is arresting. Among the developments worthiest of gratitude is the gradual reclamation of poetry’s traditional modes and roles. For instance, there’s Anthony Esolen’s The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (2019), which engages the different registers of Christian devotional verse. There’s Malcom Guite’s Sounding the Seasons: Poetry for the Christian Year (2012) and David’s Crown: Sounding the Psalms (2021), which are aesthetically and theologically tight, without any of the nostalgic affectation that occasionally inspires me to wear a bowtie. University of Chicago medievalist Rachel Fulton Brown has established the Dragon Common Room for Christian Poets, which describes itself as “…a team of poets and artists who write and publish original stories anchored in traditional Christian symbolism.” Their debut publication is Centrism Games (2021), which “depicts in bloody detail the twisted machinations and comic horrors of our amoral social quest for virtue in an era of extreme tolerance. Based on the heroic form of Alexander Pope’s mock-epic Dunciad [1728], this tale of anti-chivalry is for adults with the stomach to question their personal idols, revealing the games we play to stay safely in the centre.”

Redemptive glimmers exist, however; and amid our generalized anxiety and hopelessness, any glimmer is arresting. Among the developments worthiest of gratitude is the gradual reclamation of poetry’s traditional modes and roles. For instance, there’s Anthony Esolen’s The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (2019), which engages the different registers of Christian devotional verse. There’s Malcom Guite’s Sounding the Seasons: Poetry for the Christian Year (2012) and David’s Crown: Sounding the Psalms (2021), which are aesthetically and theologically tight, without any of the nostalgic affectation that occasionally inspires me to wear a bowtie. University of Chicago medievalist Rachel Fulton Brown has established the Dragon Common Room for Christian Poets, which describes itself as “…a team of poets and artists who write and publish original stories anchored in traditional Christian symbolism.” Their debut publication is Centrism Games (2021), which “depicts in bloody detail the twisted machinations and comic horrors of our amoral social quest for virtue in an era of extreme tolerance. Based on the heroic form of Alexander Pope’s mock-epic Dunciad [1728], this tale of anti-chivalry is for adults with the stomach to question their personal idols, revealing the games we play to stay safely in the centre.”

Schools are also rediscovering real poetry. I teach at the Hillsdale College-affiliated Columbus Classical Academy, a member of a fast-expanding family of primary and secondary schools devoted to the propagation of Goodness, Truth, and Beauty. We revere poetry, along with the other “high” arts. Central to our program is the study, memorization, and public recitation of canonical verse. At Morning Assembly, we’re daily treated to the drama of children (some of them very young, indeed) reciting swaths of Dickinson, Frost, Keats, Kipling, Longfellow, Shakespeare, and Tennyson with confidence and accuracy. First beholding this miracle was quite something. It reminded me of the yazh, a Tamil harp. Although it had long ago gone extinct, modern luthiers are again building them, basing blueprints on scholarly conjecture. Imagine what it must have been like to hear the first notes produced by the resurrected yazh. It must have sounded like a voice from beyond the grave.

Any means of connecting with tradition comes as a necessary relief nowadays. In an age when roughly fifty percent of our countrymen believe that you can have a penis and still be a woman, or that you can indulge in Hieronymus-Bosch-level savagery (such as we find in Hamas) without forfeiting your right to the sympathy of those committed to “social justice,” or that organic living, sensitivity to the unique wisdom of Nature, and fervent anti-Capitalism are obviously compatible with aborting your unborn child if failing to do so would undermine your chances of becoming an upscale lawyer … in such an age, a bit of tradition can feel like a cool breeze on an August afternoon.

***

Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek reminisces about his early career, when Western academics suspected that he must be a fictional character confected by some avant-garde theater troupe. Žižek is, at the very least, unlikely: a Ljubljana-born Lacanian psychoanalyst, lovably ursine, with a vaguely deranged bearing and an insufficiently ironic soft spot for Stalin, always ill-dressed, expounding on popular cinema through a tornado of spastic tics.

The Western academics’ instincts were well-tuned, for great art is unlikely, disorienting, and slightly preposterous in the same way. Sir Roger Scruton posits that the experience of great art is the experience of homecoming. It seems, however, that the opposite is just as often the case: great art is mystifying. Great art is, to whatever degree, weird.

Eugene Nadelman: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse, by Portland State University professor of Jewish Studies Michael Weingrad, demonstrates some of this redemptive weirdness. The plot is conventional enough. Eugene is a teenager coming of age in a milieu that’s one part Jewish Philadelphia, one part ‘80s American pop culture. Boy meets girl. Her name is Abigail, and she’s Eugene’s Dark Lady: supple, and dusky, and highly intelligent, and possessed of that innocence that only the experienced can fully appreciate. (The genuinely innocent feel their condition not as blissful purity, but as vague, generalized confusion.) Eugene and Abigail fall in love—a stormy adolescent love of the sort that’s sweet to remember, but harrowing to undergo. Since it’s fated that such love cannot last, their love, faithful to the archetype, collapses under predictable circumstances.

Weingrad confesses that it’s largely autobiographical. Evelyn Waugh observes in his own autobiography, A Little Learning (1964), that writing about one’s past places one at risk of committing two related transgressions: (a) depicting oneself as more precocious than one really was, and (b) depicting oneself as more inept than one really was. These countervailing temptations are both born of vanity. The first sin juxtaposes an inherently disappointing present with the past, which, being past, sits still long enough for the author to perform cosmetic surgery on it. The second sin advertises his current virtue while dismissing earlier, unflattering versions of himself.

All told, it’s the risk of sentimentalism that predominates. And Eugene Nadelman might have been sunk into cloying nostalgia were it not for Weingrad’s startling technical decisions, for Eugene Nadelman sounds perfectly conventional only until we consider the mode of storytelling. Of course, the tradition of poetry as a narrative art is at least as old as the tradition of poetry as a means of expressing undying love, or of commemorating the dead, or of kvetching about injustice. Chaucer and Milton, two of England’s three canonical heavy hitters, were essentially storytellers. And as for Shakespeare, while everybody knows the plays and sonnets (if only by reputation), one of his weightiest achievements is in narrative verse: The Rape of Lucrece (1594), which provides more insight into the psychology of sexual violence than any criminology textbook will ever manage. Continuing down the canonical totem pole, we find Edmund Spencer’s The Faerie Queene (1596), Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1712), Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), and Lord Byron’s verse novels Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and Don Juan (1812 and 1819, respectively), which were sufficiently popular to make their author the first modern celebrity.

In 2024, however, a verse novel comes as a surprise—especially a verse novel set in a world where pop-culture icon David Bowie, Chasidic folksinger Shlomo Carlebach, and John Milton’s pastoral elegy “Lycidas” coexist. Eugene Nadelman is an homage to one of the most iconic verse-novels, Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (1833), for which the poet invented a literary form (the so-called “Pushkin sonnet”), which is as definitively identified with Eugene Onegin as terza rima is with Dante’s Divine Comedy. Like an English or Italian sonnet, Pushkin’s version has fourteen lines. But the rhyme scheme is peculiar: aBaBccDDeFFeGG, uppercase letters indicating “masculine” rhymes (i.e., the sort of rhyme we’re all used to, where the emphasis lands on each line’s final syllable—e.g. “go” / “know”), and lowercase letters indicating “feminine” rhymes (where each line’s final syllable is unstressed, and the rhyme hits on the penultimate syllable—e.g. “going” / “knowing”).

There’s something inherently whimsical about feminine rhymes, making them rich occasions for the highest form of playfulness: the sort that’s disciplined by skill. In the Introduction to his 2016 translation of Pushkin’s masterpiece, Anthony Briggs comments on its playfulness, which can seem magically extemporized. “[D]on’t be fooled by the seductive idea of serendipity,” he warns us. “Complex organization by a master intelligence is the name of the game. […] [I]t isn’t magic, it isn’t luck; it is creative genius in a holiday mood.” The same could be said of Eugene Nadelman.

Some of Weingrad’s most playfully resourceful feminine rhymes include “cradle” and “Nadel-/man”; “Michael Jackson” and “air-raid klaxon”; “reminisce in” and “listen”; “gallants” and “balance” (Stephen Sondheim reflects on the unique pleasure afforded by rhymes where shared sounds are generated by unshared consonants); “sofa” and “loaf. A / Young woman”; “process” and “albatrosses”; “try on” and “Zion”; “all a” and “Valhalla”; “Tristan’s” and “nonexistence”; “because it” and “deposit”; “bliss of” and “missive”; and “discotheque all” and “rec hall”.

Many of Weingrad’s best rhymes play with regional accents. For instance: “endocrinal” (pronounced Britishly, with an emphatically long i) and “vinyl”; “shelf, you” (“you” pronounced ya, East-Coast-ishly ) and “Philadelphia”; “skulking” (pronounced skulkin’) and “Tolkien” (given the American spin: heavily trochaic, with the e doing more of the heavy lifting than the i); and “Paris” (the a pronounced in the pinched fashion of the Upper Midwest) and “chair is”.

In each of these specimens (excepting the penultimate), the second word tells us how to pronounce the first. When we read “I will say this: check any shelf, you / Won’t find a better novelette / In Pushkin sonnet form that’s set / In early ‘80s Philadelphia,” we’re struck by the apparent dissonance. After a moment of head-scratching, we find ourselves reverse-engineering the pronunciation of “shelf, you” based on that of “Philadelphia.” And we feel as though we’re being affectionately teased.

Poet Robert Creeley famously maintained that “Form is never more than an extension of content.” This axiom is incomplete; sometimes, much of a poem’s power comes from the apparent incongruity of form and content. In his Introduction to the Fagles translation of The Aeneid, Bernard Knox writes: “Like most Roman poems, the Eclogues […] have a Greek model. In this case it is the poems of Theocritus, […] who, writing in the Doric dialect of the western Greeks, invented a genre of poetry that used the Homeric hexameter for very un-Homeric themes: the singing contests, love affairs, and rivalries of shepherds and herdsmen[.]” William Wordsworth does something similar in The Prelude; Or, Growth of a Poet’s Mind; An Autobiographical Poem (1850), a posthumously published calamity of the most prolix and self-important kind. Wordsworth attempts to elevate his moistly nostalgic reveries by rendering them in that Miltonic blank verse we’ve come to associate with uppercase-S Significance. Simon and Garfunkel do something similar (although they do it better than Wordsworth) in Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme (1966), when they superimpose upon the Christmas standard “Silent Night” a simulated radio broadcast in which the newsreader reports with cool professionalism on recent episodes of violent crime, disorder, and generalized mayhem. It’s the very friction between form and content that sparks the pyrotechnics.

In Eugene Nadelman, this friction is nowhere as expressive as when a Hebrew or Yiddish word is yoked, often via feminine rhyme, to an English word: “mitzvah” (“commandment”) and “its va-/riety”; “olev” (as in “olev hashalom,” “peace be upon him”—the phrase traditionally appended to the name of someone who’s died) and “pall of”; “Neveh Shaloms” (“abode of peace”—plural’d as if in English) and “columns”; “bima” (the synagogue platform from which the Torah is recited) and “schema”; “kinneh horres” (“without the Evil Eye”—also plural’d à la English—, reflexively appended to the announcement of good news) and “Cousin Laura’s”.

In nearly all of these appearing in the book’s first half, the Jewish word comes first. Weingrad thereby enacts rhetorically Eugene’s attempt to reconcile his Jewishness with the Gentile literary tradition from within which the poem is crafted. For instance, “bima” and “schema” look preposterous together. The former’s metrical context indicates a warm Ashkenazi pronunciation, where the stress is placed energetically on the first syllable. As it’s used here, “bima” sustains a nimbus of associations encompassing everything that’s comfortable and folksy; it’s funny to find it rhymed with anything so stiffly Latinate as “schema.” But “bima” is the newcomer here, and must accommodate itself (however gracelessly) to a world defined by “schema.”

Writers have long capitalized on the comedic potential of Ashkenazi names, which are often intrinsically goofy. A name like, say, Schmulka Bernstein (once attached to a well-known kosher restaurant on Manhattan’s Lower East Side) functions both as punchline and premise. But the real comedic punch comes from the disagreement between Jewish names and what they represent. It’s funny enough that I shared a world with someone named Schmulka Bernstein. My mirth ramifies when I recall that it’s his kinsmen being referred to when God makes some of His most operatic pronouncements. Austro-Hungarian Jewish writer Joseph Roth, drifting through interwar Europe, amuses himself with a similar reflection: “Women and children clustered in front of fruit and vegetable stands. Hebrew letters on shop signs, on nameplates over doors, and in shop windows, put an end to the comely roundness of European Antiqua type with its stiff, frozen, jagged seriousness. Even though they were only doing commercial duty, they called to mind funeral inscriptions, worship, rituals, and divine invocations. It was by means of these same signs that here offer herrings for sale, phonograph records, and collections of Jewish anecdotes, that Jehovah once showed himself on Mount Sinai.” When we juxtapose the monumental with the trivial, we achieve something called “bathos”; it’s the beating heart that animates some of Woody Allen’s best one-liners, to wit: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work; I want to achieve immortality through not dying.”

Versions of this discrepancy are on regular display in Eugene Nadelman. For instance, reference is made to a “bar mitzvah fête.” Although “fête” derives from the Old French feste (“celebration”), it could just as easily have derived from a Latin root meaning “a goyishe garden party where everyone drinks Clover Club cocktails while endeavoring to canoodle with someone else’s spouse.” At least before East Coast Jews busted through some of their culinary provincialism in recent decades, “bar mitzvah” suggested chopped liver sculptures, a cumbersome “one-man band” (an oxymoron if ever I heard one), and strategic speculation about which door would produce the “Viennese table” (a buffet on wheels), and exactly when.

The significance of “bar mitzvah fête” deepens when we learn its context. Eugene is reflecting on Christmastide, which is often bewildering to a young American Jew—bewildering, and emblematically so. “Though Jewish,” says the narrator, “he enjoys the gleam / Of Christmas lights still up. They seem / To celebrate his anniversary, / And it occurs to him tonight / That, if he has his story right, / A barn once functioned as a nursery? / Then surely a bar mitzvah fête / Can birth a love immaculate.”

Another comedic point is scored with “…if he has his story right”; although the tone suggests the sort of flippancy with which one might refer to some family anecdote, the narrator is talking about Christ’s Nativity. (Owing to Christ’s ethnicity, however, the chronicle of His life is, indeed, for the Jewish reader, a family anecdote of sorts.)

Only gradually do we find Hebrew and English yoked together in rhyme, but where the English appears first. We get “won. Is” and “rachmunes” (“mercy” or “pity”); we also get “poem” and “makom” (“place”), where the narrator lists other tales using the Pushkin sonnet: “My favorite, and what made me try a / Rendition of the Pushkin poem, / In fact’s a Hebrew book: Makom / Aher v’ir zarah[.]” To make it rhyme with “Makom,” we’re invited to pronounce “poem” monosyllabically, which is curious, since every other time the word appears, it’s within a metrical context presuming two syllables, to wit: “Well, let’s resume our poem’s quest…”; “Our poem’s long-lost storyline…”; “Let’s meet our poem’s Tatiana…”; “I hope the poem will remind us…”; and “So make the poem an incentive…”

The energy generated by rhyming Hebrew or Yiddish words with English is conspicuous by its absence near the beginning of Chapter Four, where Hebrew words are arranged to rhyme with other Hebrew words: “The place for swimming: the brechah, / A singalong is called shirah, / Shabbat shalom’s the sabbath greeting, / The rec hall is the mo’adon, / And cleanup time is nikayon.” Hebrew is a rhyme-rich language; generally, any two words in the same form will rhyme. One appreciates the formal stress and musical daredevilism quickening the rest of the poem by registering the lyrical sogginess that settles in when polyglottal rhymes give way to uniformity. Eugene Nadelman is best when the tensions experienced by its protagonist are echoed in the poem’s formal commitments.

Tensions propel it—and not just those adumbrated above. There’s a fruitful tension between “high” and “popular” culture. John Milton’s pastoral elegy “Lycidas” (1637) surfaces in a disquisition about Dungeons & Dragons. I confess to knowing little about D&D. It belongs to the same cultural bubble that has for so long provided warmth and shelter to hormonally-imbalanced, pimple-prone suburban boys—lads who (somehow) take real pleasure in anime, study Japanese, and can spot (and then expatiate ad nauseum upon) the relevant differences between a Merovingian battle-axe and a Swiss halberd. When a D&D enthusiast sires offspring (not a trivial accomplishment for those afflicted with such listless sperm motility), the offspring often resemble axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum), and can engage in cutaneous respiration. D&D players seemingly prove one of postmodernism’s central tenets, namely, that sex and gender aren’t always in perfect lockstep.

Anyhow, in chronicling a game of D&D, the narrator writes: “And though with wizard’s blood beslabbered / The warrior is not dismayed / At all. First wiping clean his blade / He slides it back into its scabbard. / We pause now for a threnody, / Part ‘Lycidas,’ part D&D.” The specter of “Lycidas” returns a bit later, also vis-à-vis Dungeons & Dragons: “As for us, / With sighs, with faces serious, / And with apologies to Milton, / We shift our packs and head out to / Adventures fresh and dungeons new.”

“Lycidas” exemplifies the weirdness of great art. For a threnody (a mourning poem), it’s unnervingly cold and cerebral. The pastoral elegy is a genre inherited from Greece and Rome; in it, the poet (likely a cosmopolitan intellectual in real life) reimagines himself as a farmer, and, inhabiting the idealized landscape of Theocritus and Virgil, laments (using a “rustic” idiom) someone’s death. There’s a lively Christian tradition of metaphors associating religious leaders with shepherds. Grafting this onto the main bough of pastoral convention, Milton supplies himself with the opportunity to kvetch about bad priests, who don’t have any concerns beyond “how to scramble at the shearers’ feast / And shove away the worthy bidden guest. / Blind mouths! that scarce themselves know how to hold / A sheep-hook, or have learned aught else the least / That to the faithful herdsman’s art belongs!”

The poem’s end overhauls our perspective. We’ve become so invested in the poem that we’ve forgotten that a fictional character is delivering it. But then, we read the coda: “Thus sang the uncouth swain to th’ oaks and rills / While the still morn went out with sandals gray. / He touched the tender stops of various quills, / With eager thought warbling his Doric lay; / And now the sun had stretched out all the hills, / And now was dropped into the western bay. / At last he rose, and twitched his mantle blue: / Tomorrow to fresh woods, and pastures new.” As with Weingrad’s use of regional accents when rhyming (where we must rewind a few lines to identify the rhyme that—in a sense—has already occurred), having read Milton’s coda, we must rewind to the poem’s beginning to figure out what we’ve just read.

Pastoralism is inherently nostalgic, positing a Golden Age analogous to the Garden of Eden. It’s a tradition stretching from Theocritus to Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion. A twenty-first century nostalgic poem (by a witty Philadelphia Jew) referencing a seventeenth century nostalgic poem (by a mirthless English Puritan) in order to illustrate a point vis-à-vis Dungeons & Dragons, which is itself an exercise in nostalgic fantasy, all of it expressed via the intensely self-aware use of a nineteenth century verse form (invented by a half-Moorish Russian)—isn’t this exactly the kind of multiculturalism to which any thinking man would immediately pledge his allegiance?

***

Although the Wittgenstein name is most readily associated with philosopher Ludwig, his brother Paul was apparently the best one-armed pianist in the world. Their sister Gretl said of Paul: “[H]is playing has become much worse. I suppose that is to be expected, because he insists on trying to do what really cannot be done. […] Yes, he is sick[.]”

Great art emerges from the single-minded mission to do the inherently undoable. In “The Name and Nature of Poetry,” A.E. Housman writes: “[N]othing more than perfection can be demanded of anything: yet poetry is capable of more than this, and more therefore is expected from it. There is a conception of poetry which is not fulfilled by pure language and liquid versification, with the simple and (so to speak) colorless pleasure which they afford, but involves the presence in them of something which moves and touches in a special and recognizable way.”

What Housman is celebrating isn’t mere difficulty—the sort whose absence inspires T.S. Eliot to lament “the horror of the effortless journey[.]” Rather, he’s describing a difficulty existing somehow beyond Difficulty itself. It’s an “Ecstatic Difficulty,” analogous to Werner Herzog’s concept of “Ecstatic Truth” in filmmaking. It’s the difficulty implied by Confederate-American poet William Gilmore Simms when pronouncing that it’s the poet’s duty “to extort from every subject its inner secret.”

While delusional standards might have a souring effect on, say, a marriage, they can be, for the artist, downright redemptive. It’s odd that poetry suffers the reputation for emotional excess; in formal poetry (i.e. real poetry), technical demands act like bowling alley bumpers. A heavily nostalgic or sentimental poem will fail if it ignores those traditional rules that prevent unnecessary digressions. Draconian rules prevent unseemly emotional effusions.

Eugene Nadelman’s narrator understands this. He says: “And even those who warm / To ‘80s tunes may find the form / I’ve used off-putting. In all candor, / I’ve turned to it in part because / It helps camouflage my flaws[.]” He’s very nearly right. The form is off-putting: not to the reader, however, but to the poet. In selecting a form that requires him to transcend his own emotions, he elects to be put-off, expressly so that his reader won’t be.

***

I’d be badly shortchanging Eugene Nadelman if I left the impression that it’s some sort of bloodless experiment in form, for it has spells of poetic force that transcend technique—but (of course) wouldn’t be possible without it. Chapter One, for instance, finds Eugene at a dance. At every school or youth-group dance I’ve ever attended, the girls thronged in what Weingrad calls “herd formation,” which establishes a pseudo-sacred geography (as it were) on the dance floor, separating the Cool Kids from Everybody Else. Eugene, sadly, “isn’t bold / Enough to enter. In frustration, / He stands outside and sways in awe / Like Kafka’s man before the Law.”

Kafka’s parable “Before the Law” (1915) concerns a pilgrim who finds a door to the “Law”—the details or significance of which go unexplained. He spends his life camping out before the door, which (oddly) remains opened. The only thing barring his entry is the guard, who troubles the pilgrim’s sense of purpose with warnings regarding the other guards, who, though purportedly gruesome, the pilgrim cannot actually see.

W.H. Auden writes that poetry’s role is to assign “names” to experiences that we’ve had, but never saw as belonging to a recognized, discrete category of human phenomena. The poet is therefore like Adam in Genesis, charged with naming the animals—a project involving the establishment of categories. To name a zebra a “zebra” requires that we identify those traits qualifying a large, equine beast for membership of that category. And then—ecco!—we can discuss zebras.

Most American males can recall the panic, half-spiritualized yearning, rickety hope, and existential disorientation that may beset lads at a dance. And now, that experience has, if not a name, then certainly an image which reifies it: “In frustration, / He stands outside and sways in awe / Like Kafka’s man before the Law.” I’ll certainly share these lines with my sons when (God willing) they reach adolescence. They’ll know precisely what they’re experiencing while they’re experiencing it. That experience is now officially a Thing. Thank you, Poet.

Eugene Nadelman undertakes more oblique (though no less satisfying) exercises in definition. We learn that neither of Eugene’s parents has “much forbearance / For bombast, blood- and death-obsessed, / So KISS, like Wagner, fails their test.” Within a single couplet, Weingrad sketches an entire aesthetic temperament. It’s simultaneously startling and somehow obvious to hear it proposed that Wagner sheds light on KISS; it’s still more startling to hear it proposed that KISS sheds light on Wagner. It’s a treatise in sixteen syllables.

Another example of Weingrad’s skill at poetic compression: Abigail’s parents

“didn’t want a sequel / To what their single stork had brought. / They treat their daughter as an equal / And sometimes as an afterthought.” Just try to compose a quatrain as correctly balanced and as limber in its glissade from goofiness to tragedy.

I risk being a bore, simply quoting and effusing. One last example, I promise. Summer is at its height, and “[t]he very road’s a devil’s carpet, / The asphalt oozing like a tar pit, / And all the city in a haze / Of sultry air and stale clichés[.]” My face puckers with envy at such competence.

Although Eugene Nadelman is (in a sense) a portal to a distant world of dubious reality (for such is nostalgia’s nature), what Weingrad describes isn’t totally a dream. I’ve seen it, having had a childhood not unlike Eugene’s. It feels like an eternity ago.

I write this on the very brink of summer, while my adolescent pupils sit their final exams; I wonder about the world readying itself to receive them. To what extent is Eugene’s romantic coming-of-age even possible in a world as demystified as ours? Children can access unlimited porn, in which human genitals are as unyieldingly illuminated as the lot attached to a Toyota dealership. Nothing escapes the glare, not even our reservoirs of “family-friendly” information. Wikimedia Commons has images that are so literal-minded and light-bleached that clinical photos of seborrheic dermatitis seem, by comparison, to have come from Yousuf Karsh. Eugene Nadelman mentions many ‘80s pop songs. Compare even the basest among them with Bloodhound Gang’s “The Bad Touch” (1999)—an almost perfectly disgusting tune, whose chorus goes, “You and me, baby, ain’t nothin’ but mammals / So let’s do it like they do on the Discovery Channel.” The distance between the Nadelman playlist and “The Bad Touch” is so gaping that it’s scarcely believable that it was traversed in a single generation.

To what extent is the death of true Eros responsible for our sense of alienation? Introducing her translation of The Song of Songs, Chana Bloch writes that the poem’s two characters “delight in the sound of the first-person plural: ‘our bed,’ ‘our roofbeams,’ ‘our rafters,’ they say, ‘our wall,’ ‘our land,’ ‘our doors,’ taking possession, as a couple, of the world around them.” Eros makes the world our world.

Love is mysterious. In a poem quoted by Bloch, Robert Herrick declares: “I write of youth, of love, and have access / By these to sing of cleanly wantonness.” “[C]leanly wantonness”—what a phrase! It invites us into a mystery as beguiling as the Virgin Birth (birth requiring, ipso facto, non-virginity), the Splitting of the Red Sea (the splitting of a medium that, almost by definition, can’t be split), and, indeed, poetic composition itself. For the only thing more mysterious than love is the creative spirit behind superb works of literary art—works, in fact, like Eugene Nadelman. To the general reader, Weingrad has offered a new source of pleasure; to poets, he’s extended a serious challenge. Any poet who’s alive to the traditional magic of well-organized words will greet Eugene Nadelman with envy—envy of a colleague who, with apparent effortlessness, can tell a story with such charm, exacting workmanship, obvious love, and what Eugene’s grandparents would (like my own) call “ziskeit”—sweetness.

A.E. Housman was once approached by an admirer who was curious about how one might define “poetry.” Housman replied that he could “no more define poetry than a terrier can define a rat, but that I thought we both recognized the object by symptoms which it provokes in us.” And so it is. We can define a thing by how it makes us feel. Professor Weingrad’s readers will therefore denominate Eugene Nadelman a gift.

The Muses must be gratified to have Weingrad as their instrument; and I, for one, am gratified by the discovery that the Muses can apparently speak a bit of Yiddish.

Table of Contents

Jeffrey Burghauser is a teacher in Columbus, Ohio. He was educated at SUNY-Buffalo and the University of Leeds. He currently studies the five-string banjo with a focus on pre-WWII picking styles. A former artist-in-residence at the Arad Arts Project (Israel), his poems have appeared (or are forthcoming) in Appalachian Journal, Fearsome Critters, Iceview, Lehrhaus, and New English Review. Jeffrey’s book-length collections are available on Amazon, and his website is www.jeffreyburghauser.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast