Crude Cruelty

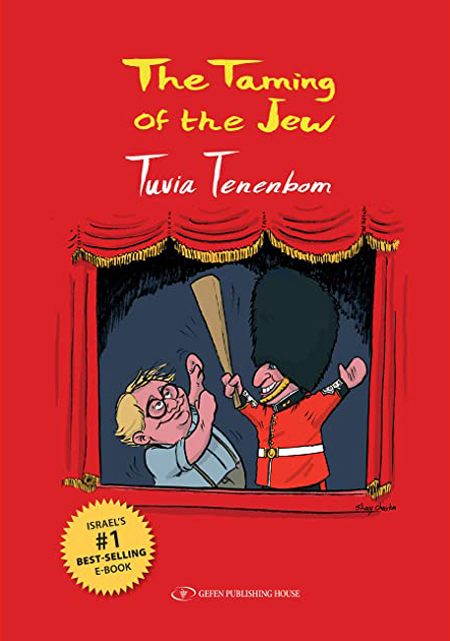

The Taming of the Jew, by Tuvia Tenenbom

by Ardie Geldman (July 2021)

The Taming of the Jew is author Tuvia Tenenbom’s fifth book in a series of decidedly curated travel journals documenting his sojourns in countries where he seeks out and encounters antisemitism. His latest book is the distillation of roughly six-months of travel during 2019 throughout the United Kingdom, including the independent Republic of Ireland.

Tenenbom’s iconoclastic interviewing technique and his playful, informal writing style have contributed to his somewhat controversial reputation. His field method is a kind of “gonzo journalism” in that his persona and his undisguised subjectivity play a role in the way he gathers information. Furthermore, where he goes and with whom he meets is almost arbitrary. To decide these, he relies upon his intuition, perhaps some pre-existing knowledge, or a spur of the moment notion to check out some person or site that sounds interesting. His interviews may be spontaneous and informal, perhaps a chance encounter on the street or in a pub, or they may be arranged by way of appointment and held in a formal setting; in other words, whatever works.

Tenenbom also favors the “Borat style” interview. His modus operandi is not to be forthcoming about his identity. He carries a German press card and most of the time presents himself as German. As he explains: “Often, when interviewing people whom I don’t know, I tell them I’m a German journalist by the name of Tobias. In my experience, people respond more honestly to me when they think that I’m German. Sometimes, if the circumstance so designs, other nationalities come out of my mouth.” These personae include Jordanian, Palestinian, and even . . . Jewish.

Tenenbom, of course, is Jewish. He was born to Orthodox Jewish parents in B’nei Brak, Israel. While still a young man he left behind both Israel and Jewish religious practices and relocated to New York. His varied career has included theater director, playwright, author, journalist, and essayist. He is the founding artistic director of the Jewish Theater of New York. According to his Wikipedia entry, he holds university degrees in mathematics, computer science, dramatic writing and literature.

Tenenbom’s writing style is also distinctive. When not quoting his subjects, he speaks directly to his readers as if he is standing before a live audience. His ongoing commentary is peppered with much sarcasm and irreverence. For example, he fantasizes about former US President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton’s sleeping arrangements when lodging in the same Londonderry hotel, or his description of London’s Royal Academy of Arts current exhibition as “big wood statues of naked men and small penises . . . ”

Most of his interviews are brief, consequently so are most of his chapters, each one generally dedicated to a single vignette. But there are enough short chapters to comprise 487 pages of text, sans index and maps, both which would have aided the reader.

The Taming of the Jew, as do all his other travel journals, comes across rather humorously. Some might find this odd for a book dedicated to so solemn a topic. However, a la Groucho Marx, Tenenbom employs humor to thumb his nose at the antisemitism (and the antisemites) he encounters. The Taming of the Jew is a serious book, but consciously written in light-hearted prose.

There is still another feature to this book that could be distracting. The author quite often wanders off-topic, shifting his attention to matters unrelated to antisemitism.

For example, perhaps to give readers the sense of being there with him, Tenenbom takes pains to comment in detail on his surroundings, his lodgings, the ambience of restaurants and the food he is served. We soon come to learn, and are often reminded, that Tuvia Tenenbom’s favorite libation is Diet Coke and that he loves to eat. He views himself both as an epicure and a gourmand, offering us his critique of the Irish, Scottish, British and Welsh fare in which he indulges and compares these with the Middle-Eastern dishes he manages to find. Moreover, he opines on matters as diverse as the natural beauty of the countryside and coastlines, the grandness of the cities’ architecture, the varying standards of his different hotel accommodations, the physical condition of UK cities and towns, and the quality of each country’s theatre and television productions. As a result, with a pinch of exaggeration, the book might be taken for a Lonely Planet Guide to the British Isles.

An even greater distraction is Tenenbom’s preoccupation with the UK’s “Brexit” controversy, then at its peak. As an outsider he claims to be neutral on the issue. Nevertheless, he makes no effort to hide his pique at the “Remainers” who, as he puts it, feel that the national referendum they lost was undemocratic simply because they lost. He takes up the topic of Brexit with many of his subjects, but not antisemitism. A relatively long chapter in the book is dedicated to his London meeting with Nigel Farage, a former MP and leader of the Brexit movement, during which antisemitism is barely mentioned. It is almost as if Tenenbom, finding himself fascinated by the controversy over Brexit, chose to write a single book but about two topics. He alludes to this duality when he writes “The two greatest shows on earth are playing in London right now, real-life absurdist dramas: Brexit and antisemitism.”

There is also a seemingly disproportionate amount of narrative dedicated to his efforts to track down and arrange an interview with then-British Labour Party head Jeremy Corbyn. He describes in great detail, on-and-off in a number of chapters, the cat and mouse game he plays with Corbyn, whom at times he flippantly refers to as “JC.” In spite of a photo in the book in which the two stand side by side smiling, the sought-after interview never happens. In the end he describes Corbyn as “a really nice man who really doesn’t like Jews.” At least Tenenbom’s preoccupation with Corbyn is due to his highly publicized reputation for being antisemitic.

Finally, he ventures away from his main topic with numerous critical comments on the falseness and hypocrisy he witnesses throughout much of British society, but also found among the Scotch, Irish and Welsh. He is repeatedly censorious of the inequities of the UK’s class system and the political correctness used to disguise people’s racism.

In a London theatre “I observe the people sitting next to me, and then I look on the stage. What an interesting study in opposites; while the actors on the stage are mostly black, there are no blacks in the audience. In London’s supposedly classless society, the blacks entertain themselves at McDonalds—which is where I saw many of them on my way here—and the whites entertain themselves at the West End, watching the blacks playing black music for them and making them feel like liberal, modern, black-loving whites. I smell the odor of racism entering my nostrils.

So, putting aside British food, Brexit, Jeremy Corbyn, and social injustice, what does Tenenbom learn about antisemitism in the UK which is ,after all, the raison d’etre of his book?

It should come as no surprise that he finds it, and plenty of it, and throughout all four United Kingdom countries. His encounters begin in Ireland. Following initial escapades in Dublin, Belfast, Ballygally, and Carnough, he arrives in Derry. Eventually he enters a pub and introduces himself as a German reporter to a group of male patrons. He asks them about the numerous Palestinian flags he has seen in Irish cities. The response he gets is “Because we support them . . . ‘cause of the f—–g Jews.” “The Israelis are scum. Killing children.” “They stole their (Palestinians) land and killed the poor children.” “(Hitler) didn’t kill enough f—-g Jews. The scourge of the world.” Tenenbom then asks them: “Have you ever seen a poor Jew?” Response: “They all have money, they’re all rich.” Tenenbom: “Are there Jews in Ireland?” “No, we got rid of them.” His conclusion: “The island of Ireland, be it the Republic of Ireland or Northern Ireland, is saturated with Jew haters, the biggest Jew haters of our time . . . ”

From Ireland it is on to Scotland, where he writes “I just arrived in Scotland, and ‘Palestine’ is already popping up in my face.” In Scotland, as he already discovered in Ireland and as he will discover to be the case throughout the United Kingdom, pro-Palestinian/anti-Zionist fervor is often difficult to separate from antisemitism. For example, in 2013, “the Church of Scotland issued a document entitled ‘The Inheritance of Abraham? A Report on the Promised Land.’ It asserted, among other things, that ‘Christians should not be supporting any claims by Jewish or any other people to an exclusive or even privileged divine right to possess particular territory.’”

Tenenbom boils this down to “If you, Jews, thought you were special, we got news for you, you are not.” At the time of his visit the leaders of Edinburgh’s small Jewish community and the Church of Scotland were still not on speaking terms. In Glasgow, members of the Jewish community prefer to “run away” rather than meet with him, paranoid with the fear that speaking out about Scottish antisemitism could cause them to lose their National Health Service insurance. They are among the U.K.’s tamed Jews. Finally, as a demonstration of how convoluted antisemitism can be, Tenenbom relates having met a Scot who tells him: “Israel is a great place, but people don’t understand this. People think that Israel is connected to Zionism, which it totally false. Israel has nothing to do with Zionism.”

England, home to the largest Jewish community in the United Kingdom, naturally gets most of Tenenbom’s attention. Here he travels more extensively, making relatively short visits to a number of smaller population areas, some of which people living outside of the UK may have never heard of. At the “ultra-Orthodox” yeshiva in Gateshead, “the most prominent British yeshiva,” he admits to lacking sympathy for these tamed Jews who, “mindful of the constant news about antisemitism in Britain’s mainstream party these days, are living in fear, ever afraid that they will be slaughtered once more (as were English Jews in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries).” But still they do nothing.

England’s two largest Jewish communities are in Manchester and London. While exploring Manchester, Tenenbom again encounters a “tamed Jew,” an “official of the Jewish community” who is reticent to speak with him openly about antisemitism for fear of losing his job. Of Manchester he says: “ . . . the antisemitism in the street, the antisemitism in people’s hearts, is . . . a virus, a virus that resists all known antibiotics.”

London leaves him with the same impression. There he muses, “Scratch a Brit, find an anti-Semite underneath? Maybe.” During the 2019 General Election campaign antisemitism was an open controversy following revelations of it having taken root within the Labour party. Jewish former MP Luciana Berger with whom he met was among others who resigned their long-time party membership. She characterized the Labour Party as having become “institutionally antisemitic.”

At the end of his survey of England and numerous encounters Tenenbom sums up with “. . . I thought that the issue was Jeremy Corbyn’s antisemitism, but now, after having interviewed many British people, I have come to the conclusion that the issue is not Jeremy Corbyn, but the people. It’s the (English) people who are antisemites, and it doesn’t matter what Jeremy Corbyn is or not.”

Final tour, Wales. In Cardiff, Tenenbom is disappointed in a street pastor who works with wayward young people. Not only is the clergyman’s knowledge of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict mistaken (“there are more Christians living in Palestine than are living within Israel”), but Tenenbom wonders “why a man like him, whose job it is to be in the public’s eye and preach to the people, cannot find the time and the hour to publicly condemn antisemitism in this land.”

As in Ireland, Scotland and England, so too in Wales; antisemitic prejudice is widespread. Tenenbom encounters it in city and in country, among the elite and among the more common folk. But as in the rest of the UK, the antisemitism he encounters in Wales does not involve physical violence or damage to property. This is not to say these are absent. Antisemitic bullying and vandalism, particularly anti-Israel graffiti, in fact figure significantly into the annual report by the UK’s Community Security Trust (CST) that has been monitoring antisemitism since 1984. But this is not the antisemitism that Tenenbom personally experienced.

His account of antisemitism principally repeats two themes: (1) Jews are good with money but are dishonest in their dealings with gentiles, and (2) Israelis, who are conflated with Jews, stole Palestine from the Arabs and now oppress them, especially children. This type antisemitism finds expression in people’s prejudices rather than in their actions. Irrespective of its real social and economic consequences, such antisemitism still feels less threatening than the current brute physical attacks against especially identifiably Orthodox Jews in New York.

By the end of his odyssey, Tenenbom has mustered sufficient anecdotal evidence to demonstrate what many in any case already know. First, antisemitism, though not necessarily the thuggish kind, is certainly alive and well throughout the United Kingdom. “The people of the British Isles,” he concludes, “have a little obsession with Israel and Jews, be they religious or atheist . . .”

Second, much of storied British propriety is false. In a number of withering comments, Tenenbom decries the rife hypocrisy within all four countries’ ruling groups, their politicians, their intellectuals and artists, and throughout much of society. It is but a veneer of decency and political correctness masquerading what is in fact a deep division between different racial groups, between social classes, and between haves and have nots.

As previously pointed out, Tenenbom dedicates almost as much text to this matter as he does to the issue of antisemitism. What might link the two separate topics in the author’s mind? Possibly it is how the UK treats antisemitism. True, anti-Israel sentiments in the UK are often quite public. But whatever enmity some British hold for Jews as Jews is managed with the same hypocrisy and political correctness used to camouflage their other prejudices. Perhaps it is this technique that allows them to tame their Jews.

__________________________________

www.iTalkIsrael.com.