Cuckoo

by Theodore Dalrymple (April 2024)

Recently I made mention of the cuckoo in an essay, a bird that cannot but raise deep emotional responses in us. However absurd it may be, we invest its conduct with moral meaning. To call someone a cuckoo in the nest is deeply derogatory; no one wants such a creature in his home or anywhere else.

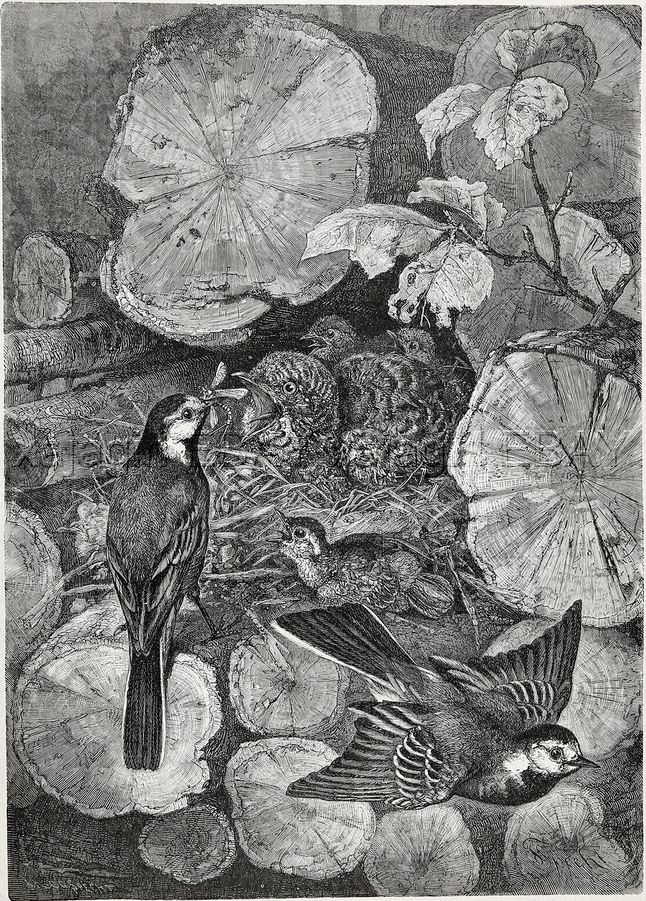

The cuckoo does not conduct itself as a good bird should, as a decent and responsible member of the ornithological community. A good bird should build its nest in spring, lay its eggs, incubate and hatch them, and then tenderly feed its fledglings until they are ready to fly the nest. It should fulfil its parental responsibilities.

The cuckoo is the very opposite of this decent bird. It is, so to speak, the welfare dependent, or cunning psychopath, of the feathered world. It lays its eggs in the nest that a member of another species has gone to the great trouble of constructing and then disappears, like the fathers of the welfare dependent’s children.

When a cuckoo’s egg hatches, the impostor fledgling takes over and either pushes its step-fledglings out of the nest to their deaths, or pushes the unhatched eggs of its foster-parents out so that they smash on the ground below. Despite this disgraceful behaviour, the cuckoo’s step-parents continue to feed the young cuckoo, even when it has grown to be several times their size. Is this mere stupidity, or is it that sense of duty that I have observed many times among human parents and step-parents who continue to care for their unworthy offspring even though to do so is against their own immediate interests? Perhaps it is even some kind of affection, for as we know, we do not always choose worthy objects for our affections.

One cannot help but feel a sense of outrage at the cuckoo’s lazy, parasitic behaviour (incidentally, there are fifty species of bird the behave in this way). Does it have no conscience? Does it never occur to it to earn its own living? True enough, the cuckoo’s migratory pattern entails considerable effort: the European variety spends but three or four months in Europe, and then flies to the Congo to winter there, as some of the European upper classes used to winter in Egypt. It takes the cuckoo a long time to fly from Europe to the Congo and back again: surely there must be an easier way for a bird to earn its living? I am reminded of perpetrators of ingenious and elaborate crimes who, if only they put their ingenuity to an honest purpose, would do far better economically than by stealing or cheating. But there is something attractive, at least to some birds and people, about living at someone else’s expense, even if one has to expend considerable energy in doing so. There is a satisfaction in itself of making a fool of others: if others are fools, one must be clever oneself.

No matter how often one reminds oneself that the cuckoo is a creature of very little brain, and cannot behave otherwise than it does behave, lacking entirely the human’s pre-frontal cortex, one never quite loses one’s disapprobation of it. You feel that if it really tried, as my school reports used to say, it could do better. It could build its nest like a good warbler or hedge sparrow, and settle down to a quite domestic existence. After all, building a nest takes less energy than flying to and from the Congo every year.

Yet our attitude to the cuckoo is not entirely negative, far from it. Let us not forget that the first poem in English to make it into anthologies is always the one welcoming the cuckoo as a harbinger of the longed-for summer. Moreover, though it is no nightingale, we love to hear its sound. It is monotonous, no doubt; but monotony can be reassuring or soothing. I can sit and listen to the cuckoo’s intermittent call for a long time and do not seem to tire of it.

When, therefore, I learn that the population of cuckoos is in a much steeper decline than that of any human population in Europe, I feel a certain sorrow, not intense but deep. The cuckoo, for all its elaborate parasitism that seems like a clever ruse, is not an adaptable bird. Each one (of the females) is adapted to laying its eggs in the nest of a particular species, and if that species itself declines in population the cuckoo that parasitizes it cannot switch to another host to parasitize. And if all or most of the host populations decline – as indeed they have – the total number of cuckoos must decline also.

I pass over the interesting question of how natural selection could have resulted in such a bird by the slow accretion of survival advantages. Would cuckoos that wintered in Burkina Faso rather than in the Congo have survived less well, and therefore those that pushed on a little further to the Congo come to have ruled the roost, as it were? I am sure that ingenious theorists of evolution by means of natural selection could find an explanation, because they can find an explanation to everything. That ability, however, is not necessarily an advantage.

But why am I sad that the cuckoo is disappearing and, if current trends continue, will soon enough become extinct? In my youth, there was a tradition of people writing in to the Times newspaper claiming to have heard the first cuckoo of spring (they—the people—seemed mainly to be old generals or admirals who had retired to the country, a species itself in the way of extinction), but that tradition has long since ended. There is more than one possible explanation for its demise, but the rarity of cuckoos cannot be it: for rarity usually increases the value or salience of an event, and would make the arrival of the first cuckoo of spring all the more interesting and important.

As I have already mentioned, the decline of the cuckoo population in Britain (much steeper than and rise or fall in the human population) saddens me, and the emotion precedes my awareness of the reasons for it: which is not the same as saying that there are no reasons for it, or that these reasons cannot be brought to mind and reflected upon. Only a very little knowledge is necessary to do so.

Like most complex phenomena, the decline of the cuckoo population is susceptible to more than one possible explanation, nor need there be a single explanation that is both necessary and sufficient. Because of the cuckoo’s complicated life-cycle, many possible changes in the environment could be detrimental to it, anywhere between the Congo and Europe. But experts agree (and I do not despise expertise) that the main cause of the decline in the number of cuckoos is the rapid decline in the numbers of the bird species that they parasitize. And then the question becomes why those species have declined in number.

The destruction of the environment is the obvious answer. The birds that the cuckoo parasitizes are mostly insectivorous, and the number of insects has declined because of the intensive use of insecticides and herbicides, and the insectivorous birds with them. In addition, the hedgerows, trees and shrubs in which the parasitized nest have also been destroyed in the search for ever-greater agricultural yields, and the marches have been drained to reclaim land for human use.

But why does the disappearance of the cuckoo sadden me? I do not think I have ever seen one, except possibly in flight: they do not lend themselves easily to casual human observation and I have never been anything more than a casual observer of what is around me. Cuckoos are quite handsome birds, with a tasteful colour-scheme, but since I have never seen one, the loss of their visual appearance cannot be the reason for my sadness. I would not regret their disappearance the less if they were uglier birds than they are.

Nor can I honestly say that the echoing invariant sound of their cry—Cuck-ooo! Cuck-ooo! —plays a large part in my life, however much I may like it. Objectively speaking, my life with and without the cuckoo would be very much the same. And yet my sadness at its disappearance is genuine and, as I have said, deep if not intense. (It seems to me a characteristic of modern emotional life that it is intense but not deep.)

What is the reason, then, for my sadness? It is partly the melancholy of loss consequent on the passage of time, but it is more than that. I know perfectly that my life would continue much as has done without ever hearing the call of the cuckoo. It is rather the loss of associations with the cuckoo that make me sad, rather than the actual loss of the cuckoo; for the disappearance of the bird means the disappearance of the environment in which it takes its being; and though I am far more urban than rural in my avocations, yet I am deeply attached to the countryside and would not like to feel that I could never escape to it from the town or city. In like fashion, there are many great monuments that I have never been to and never will go to, whose destruction I should mourn in a way that I would not mourn the destruction of my garden shed, to which I go regularly.

Of course, the countryside in England—as it once was and as pockets of it still are- is man-made: but if so, it was a masterpiece without anyone having intended to produce it. The strange fact is that one can lament deeply the disappearance of something that one experiences only intermittently and that, objectively, plays a small part in one’s life by comparison with, say, the local supermarket. It is reassuring to know that it is there, as it would be distressing to know that it was no longer there. When I am in Australia, for example, where I am no Crocodile Dundee and am as urbanised as most Australians themselves, I nevertheless experience a profound sense of relief from the awareness that, not far away, there are vast open unoccupied spaces of a kind now quite unknown to Europeans. It is not that I have a desire to cross the Nullarbor Plain on foot, or confront the deadly snakes that no doubt can ambush one there, but a subliminal awareness that the paved streets are not the whole of the world, and that one can get away from them if one so wishes, acts as a kind of balm.

Freedom is not the same as its exercise. I am free to say anything I like, but that is not to say that I do say anything that I like, or that I say the first thing that comes into my head. I could do so if I so wished, but I do not wish to do so. Nevertheless, the awareness of my freedom is a source of relief, pleasure or contentment to me, and even acts as some kind of moderating influence on me. That, perhaps, is why the attempts at censorship by the self-appointed police of political correctness, not legally-enforceable but nevertheless socially effective, so often call forth intemperate and sometimes downright disgusting explosions of outrage and opposition. It causes people to forget that it is not because someone forbids us from saying something that one ought to say it, nor does one attain the truth merely by saying something that is the opposite of a tenet of political correctness. To say something that offends may give us a moment of gratification, as a child or adolescent delights to say something that shocks the adults, but it is not the way to promote truth. Two oversimplifications do not make for a right understanding.

Censorship in the name of civility ends in its opposite. Civility, like tolerance, is a habit of the heart, and attempts at imposing it expunges it from the very place it ought to be. To change the metaphor slightly, legislation is a cuckoo in the nest.

Table of Contents

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast