Damon and Pithias: Shakespeare’s First Play

by David P. Gontar (July 2021)

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550-1604), attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger

We, Hermia, like two artificial gods,

Have with our needles created both one flower

Both on one sampler, sitting on one cushion,

Both warbling of one song, both in one key,

As if our hands, our sides, voices and minds

Had been incorporate. So we grew together

Like to a double cherry, seeming parted,

But yet an union in partition,

Two lovely berries moulded on one stem,

So with two seeming bodies but one heart,

Two of the first, like coats of heraldry,

Due but to one and crowned with one crest.

—Helena

The Issue

Who gave us Damon and Pithias? Though its straightforward moral idealism suggests a student’s hand, custom has it that Richard Edwardes, a choral musician by trade, was its progenitor. To this day the Edwardes legend has never been challenged. When it is, a world of astonishing richness and complexity unfolds before us, reflecting a far more likely authorial candidate: “Shakespeare” in his minority. Resolving the puzzle of Damon and Pithias transcends the authorial crux, providing an illuminating appendix to many of the most significant works of the English Renaissance. All may be expressed in a single encompassing syllogism: (1) Damon and Pithias was written, not by cat’s paw Richard Edwardes, but by Edward de Vere,17th Earl of Oxford; (2) Through close stylistic examination we find that whoever penned Damon and Pithias must also have crafted the Shakespearean canon; ergo (3) Oxford wrote “Shakespeare.” Thus the Gordian Knot of literature unravels at a single stroke. Let us see what advantages accrue as we explore this pregnant hypothesis.

1. Disposing of the Richard Edwardes Fantasy

A substantial quorum of the works of Shakespeare focuses on the virtues and foibles of friendship. Think of: The Two Gentlemen of Verona (Proteus and Valentine), Romeo and Juliet (Romeo and Mercutio), As You Like it (Rosalind and Celia), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Hermia and Helena & Peter Quince’s fraternal mechanicals), The Merchant of Venice (Antonio and Bassanio), The Winter’s Tale (Leontes and Polixenes), Coriolanus (Martius and Aufidius), Love’s Labour’s Lost (King of Navarre & Co.; Princess of France & Co.), Much Ado About Nothing (Claudio and Benedick), Twelfth Night (Sebastian and Antonio, Sir Toby Belch and Sir Andrew Aguecheek) The Two Noble Kinsmen (Arcite and Palamon; Flavina and Emilia) The First and Second Parts of Henry IV (Falstaff and Prince Hal), The Tragedy of Julius Caesar (Brutus and Cassius), and Hamlet, Prince of Denmark (Hamlet and Horatio). Damon and Pithias, a much older work bearing a publication date of 1571, features a pair of protagonists so devoted to each other that one, Pithias, is willing to sacrifice his life to a tyrant’s wrath when the other, Damon, is absent. On the basis of Edwardes’ moniker on the 1571 quarto it is imagined that he, a choirmaster and occasional poetaster, is the responsible party. A typical Edwardes’ writing sample cries out to the nayward.

In going to my naked bed as one that would have slept,

I heard a wife sing to her child, that long before had wept;

She sighed sore and sang full sweet, to bring the babe to rest,

That would not cease but cried still in sucking at her breast.

(“All Poetry,” Famous Poet, Richard Edwards [sic])

Jottings such as these disappoint when we seek out poetic gifts. Though he is set down as an authority on amity, it’s ironic that Edwardes doesn’t seem to have had any friends himself. The scenes of D&P abound in conflicting Weltanschauungen and evince such courtly repartee as one might expect from a Voltaire or Talleyrand. Careful study finds a yawning chasm between script and proposed scribe. Only one steeped in Hellenic ideas and manners could gracefully deploy them in a credible Renaissance stage production. Sadly, the historical Richard Edwardes cannot be shown to have possessed the technical vocabulary and genteel application to do the job. On the contrary. Where are his papers, his bons mots and billets doux? As might be expected, he passes unmentioned in standard texts treating the 16th century, e.g., A.L. Rowse’s The Elizabethan Renaissance, 1971

Professor Janet Clare in her highly esteemed “Shakespeare and Early Modern Authorship” (The Journal of Early Modern Studies, University of Florence Press, 2012, pp. 137-53), demonstrates that the typical 16th century litterateur did not consistently treat his scripts as acquisitive property in the contemporary sense, particularly after they had passed into the hands of performers or acting troupes. In that freewheeling era the handling of plays by publishers and book sellers was a rather cavalier enterprise, usually a matter of expedience and profit. It was an historical turning point, “a moment of uncertainty and transition,” avers Clare. Hence, in the case of a previously unpublished work performed by students for the Queen at Cambridge in 1564, without independent corroboration we can hardly presume that the name appearing on the 1571 frontispiece reliably represents the author’s actual identity, particularly when it is gracing a posthumous quarto. One other play linked with this fellow and staged in 1566 at Oxford University for the Queen (Palamon and Arcite), is no longer officially extant yet remains in plain sight as Shakespeare’s The Two Noble Kinsmen, another masterful portrayal of ideal friendship.

Let it be kept in mind that “Gulielmus Shaksper” (official name) was born in Stratford-Upon-Avon just prior to April 26, 1564, the very annus mirabilis we are about to examine. Ambitious yeoman though he may have become, Gulielmus was still in swaddling clothes when Damon and Pithias was first put on. He is plainly not a candidate. It is only when we turn to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, that things begin to clear up. One commentator writes of Oxford’s youth:

[Oxford] was placed in the nearby household of Sir Thomas Smith, a scholar and author who became his tutor for the next several years. In November, 1558 he matriculated at St. Johns College, Cambridge. From at least 1556, Edward’s father, the 16th Earl, sponsored his own company of actors who toured the region, and also performed for the family and their guests at Hedingham Castle, including Queen Elizabeth when she made a personal visit in 1561. In 1563, five years after he entered university, his tutor, the antiquarian Laurence Nowells, declared: “My work with the Earl of Oxford cannot be much longer required.” He was awarded a degree [M.A] from Cambridge in 1564 and a Master’s of Arts degree from Oxford in 1566. By this time he had . . . begun his lifelong practice of sponsoring works of literature, and over the next four decades more than thirty volumes of poetry or prose . . . were dedicated to him. (Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Newsletter, 12/19/05, emphasis mine)

Consider: eight years of higher education, including Latin and Greek.

It would be hard to overstate the significance of this report. It is indeed well established that Edward de Vere was raised in a manse equipped with its own theatre and actors, and that in 1561 the Queen of England debouched upon that notable household as part of her annual Progress, where she was warmly accommodated and entertained. Contemporary custodians of that residence, Castle Hedingham, offer in their official Castle Website, “Siblehedingham.com” (C093DJ), the key historical fact:

“In 1561 Queen Elizabeth aged twenty-eight stayed at Hedingham from August 14 to 19, and Edward the 17th Earl, became one of her favorites and was acclaimed to be the best of the courtier poets.” (Emphasis mine)

Recognize that this report emanates not from any woolly partisan in the authorship dispute but from official records of Castle Hedingham. We learn not only that young de Vere was a preternaturally gifted poet, but that Queen Elizabeth spent nearly an entire week as his companion. Obviously, she relished his talents. Would not the Vere family’s resident players have plied their trade for her? And would not this 11-year-old prodigy have taken part in the fun? Perhaps he even devised speeches or skits for them. Their rendezvous was a festival in miniature. Are we not put in mind of Elsinore’s hosting of the itinerant players, and the mysterious “sixteen lines” our Prince inserted in their little tragedy? (Hamlet, 2.2.542-544) Would not Elizabeth have recognized and encouraged this singularly gifted child in his theatrical vocation? With Oxford’s unique credentials rising before us the escutcheon of Master Edwardes begins to blot.

Proceed to 1562. The 16th Earl of Oxford, John de Vere, young Edward’s putative father, dies under suspect circumstances, and the brilliant student is transferred with pomp and circumstance the following year, 1563, to Theobalds Manor, Hertfordshire, the imposing residence of William Cecil, the Queen’s star counselor and newly appointed Master of the “Court of Wards.” A contemporary diarist observes: “On the 3d day of September (1562), came riding out of Essex from the funeral of the Earl of Oxford his father the young earl of Oxford, with seven score horse all in black, through London, and Chepe and Ludgate, and so to Temple Bar . . . between 5 and 6 of the afternoon.” (Charlton Ogburn, The Mysterious William Shakespeare, 1984, 437.) Edward is then officially in ward to the grand lady who had previously frolicked with him in 1561, the first of eight wards to be successively ensconced in Cecil House as her romantic affairs bore fruit. (See, Kings & Queens of England: From the Saxon Kings to the House of Windsor, Nigel Cawthorne, Arcturus, p.114.)

2. Damon and Pithias and Edward de Vere

Thus did Edward de Vere become the personal charge of Elizabeth Tudor. The stately cavalcade that brought him to the Thames adumbrated the more lavish and boisterous expedition of 1564. Summer escapades of her Majesty were usually a mile long and contained a thousand horses—transporting through the realm the entire Privy Council. (Hadley Meares, History Magazine, September 19, 2019.) Thus it was that on a Saturday evening, August 5th of 1564, the mammoth phalanx of the Queen wended its way through the entrance of Cambridge University, where the 30-year-old monarch was to polish her Greek and Latin, officiate at commencement ceremonies and savor the hospitality of academe. William Cecil, Elizabeth’s chief counselor since 1549 and Chancellor of Cambridge University, met her at the gate, (Perry, 129) and this same child of destiny, Edward de Vere, most likely stood trembling at his side. What brought Elizabeth’s Progress to so remote an event? Of all the students at Cambridge, what accounts for her continued preoccupation with this particular lad? She and Cecil had made sure his education was extraordinary. In 1564, he was now fourteen years of age, and light years ahead of his cohorts in arts and letters. And what soon thereafter prompted her to meet with him in 1566 at Oxford University to present him with yet another Master’s degree after enjoying additional theatrical performances? In summary, in 1561, 1564 and 1566, an adolescent Edward de Vere socialized with England’s reigning monarch and shared with her the wonders of the stage. In 1562 she brought him to London—permanently. On each of these occasions she went out of her way to be with him. These attentions would not go unrequited.

Cecil (Lord Burleigh) and de Vere both received advanced degrees in 1564, and, as alumnus and Chancellor of Cambridge, Cecil was responsible for arranging most of the festivities leading up to the actual ceremony scheduled for August the tenth. As Edward de Vere was graduating and officially lodged in Cecil’s residence (Court of Wards) he would naturally have been fully informed of the program and, in light of the high jinks three years earlier at Castle Hedingham, was probably invited to furnish the lead play, a signal honor. Here is a description of the next day’s program courtesy of Mark Anderson.

The following night, [Sunday] King’s College Chapel was converted into a theater with, in the words of one contemporary account, “a great stage containing the breadth of the church from the one side unto the other that the chapels might serve for houses. In length, it ran two of the lower chapels full, with the pillars, on a side.” Cecil and the other attendees, presumably including de Vere, entered bearing torches. The guards stood by the stage, providing the only source of illumination for the play. The Queen and her attendants then entered and took their seats, with Her Majesty watching from a special throne onstage. She was, after all, still the center of attention. The following day [Monday] was given over to public debates at St. Mary’s Church on such topics as art, the superiority of monarchy to a republic, and the merits of simple over complicated foods. The evening’s performance was Edward Haliwell’s tragedy Dido. A marginally anti-Catholic play followed on Tuesday night, Nicholas Udall’s drama about King Hezekiah and his destruction of idolatry. By the following evening, after another day of disputations and an extemporaneous speech of her own in Latin, Elizabeth was too worn out to enjoy any more entertainments. So she awarded degrees to the fourteen-year-old de Vere and others the next morning and then decamped for the nearby priory of Hinchinbrook. (Anderson, 30)

Perusing this remarkable description of Elizabeth’s sojourn at Cambridge we are struck by the omission of the title of the first play given on the evening of Sunday the sixth. Here we have the very cynosure of English nobility, the Queen herself, ensconced on the stage, and yet the name of the principal theatrical piece is scanted. Then in the very next paragraph we learn the later performances were of Dido and Hezekiah. We also know that later in the same year (1564) at Christmas the Queen had called for an encore of Damon and Pithias, to be directed in London by Richard Edwardes, someone not mentioned in accounts of the 1564 festivities. Obviously, there cannot have been an encore without a first performance.

It is significant that the text of Damon and Pithias has a brief epilogue, a fulsome address to the reigning monarch and guest.

The strongest guards that kings may have,

Are constant friends their state to save.

True friends are constant both in word and deed,

True friends are present and help at each need.

True friends talk truly, they gloze for no gain,

When treasure consumeth, true friends will remain.

True friends for their true prince refuseth not their death:

The Lord grant her such friends, noble Queen Elizabeth,

Long may she govern in honour and wealth,

Void of all sickness, in most perfect health;

Which health to prolong, as true friends require,

God grant she may have her own heart’s desire:

Which friends will defend with steadfast faith,

The Lord grant her such friends, most noble

QUEEN ELIZABETH

So far as we know the other offerings that week bore no such dedication. What collective parapraxis, then, would lead one to elide the featured work’s identity and author? And yet, it isn’t difficult to fit the pieces of the puzzle together. The unnamed play, first presented by torchlight the sixth of August, 1564, was surely Damon and Pithias. Elizabeth sat onstage, right in the middle of it, almost a participant, and hearkened to its praises. So delighted was she that she did ask Cecil to arrange for a repeat performance at Whitehall, which took place around Christmas time. Richard Edwardes was retained to manage, not compose it. In Tudor England royalty (including royal wards) were frowned on if they openly engaged in theatrical business, a fact confirmed by Shakespeare in King Henry IV, Parts One and Two, and Hamlet. Who, then, actually wrote Damon and Pithias? Bear in mind that it was through and through a student production. The only one qualified in training and position to craft such a script was the young man over whom Elizabeth and Cecil made such a fuss: Edward de Vere.

What we have, then, in Damon and Pithias, is nothing less than the most significant piece of juvenilia in the sixteenth century. Two years later, in 1566, all this was repeated, with an early version of The Two Noble Kinsmen composed by the Earl of Oxford and presented before Her Majesty at Oxford University, just prior to his receiving a second Master’s degree at her hands. Edwardes directed and so botched the job that there were accidents and injuries. In October he was gone.

Remember that when she would appear at places like Cambridge and Oxford Queen Elizabeth got there (and back) not in jet airplanes but in jostling carriages and wagons over many days of miserable unpaved roads. These were vital and laborious missions undertaken in search of unique recognition. Now we know the principal end in sight: the boy prodigy who captured the heart of a Queen, not an amateur scribe waving a baton. Although in his career Edwardes had printed up a fair quantity of his verses, his alleged play Damon and Pithias was unclaimed, not connected with anyone until 1571, when the friendship of Elizabeth and Edward de Vere was reaching its zenith and they wished to memorialize what they had shared. The late Mr. Edwardes’ name was affixed thereto as a decoy to maintain royal privacy. Had it really been his first play Edwardes would certainly have brought it out as his own. As he never did, he cannot have been its author.

3. Damon and Pithias: Contents and Cause

Before turning to stylometric evidence of Damon and Pithias as a Shakespearean product, a few additional remarks will be helpful. Perhaps the most prominent line in the entire canon is “All the world’s a stage.” (As You Like It, 2.7.139, circa 1598-1600, pub. 1623). But in the piece we examine here, fashioned at least thirty four years earlier, we read: “Pythagoras said that the world was like a stage, whereon many play their parts, the lookers-on the sage.” (Sc. 7, 84-85) What might such amazing synchronicity portend? Young intellectuals at Cambridge would learn it was the custom of thinkers in ancient Athens to gather on the porches of the Agora and observe at a discreet distance the antics of unwitting humanity. A music man by occupation, Richard Edwardes was hardly privy to such nuanced observations, or the ideas they engendered. Eponymous personae Damon and Pithias represent acousmatic members of the Pythagorean school of Sicily on vacation in Syracuse. They and their fellows exhibit a medley of principles drawn from various pre-and-post-Socratic philosophies, including Pythagoreanism, Platonism, Stoicism, Hedonism, and Cynicism. Lead figure of the play is the engaging rogue Aristippus, a wily egoist named after Socrates’ pupil, Aristippus of Cyrene (530-468 BC), the historical founder of Cyrenaic Hedonism. Antagonist and false witness Carisophus is the villain who unjustly accuses Damon of misconduct, bringing down on him a cruel sentence of death. When Damon is given a temporary stay of execution and fails to materialize on the date stipulated, Pithias rushes in to take his place on the block. Before the execution can be performed, however, Aristippus, an engaging blend of Falstaff and Autolycus, steps in to enlighten the Syracusan monarch and save the day. He puts us in mind of Falstaff in King Henry IV and Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale, frank and appealing figures who, in instinctively seeking their own advantage manage to do greater good than harm. Scholars have long puzzled over Prince Hamlet’s reference to “Damon dear,” (3.2.269) a seemingly gratuitous distraction which now begins to resonate, as we set the bond of Hamlet and Horatio in context. Let us now turn to some key linguistic commonalities.

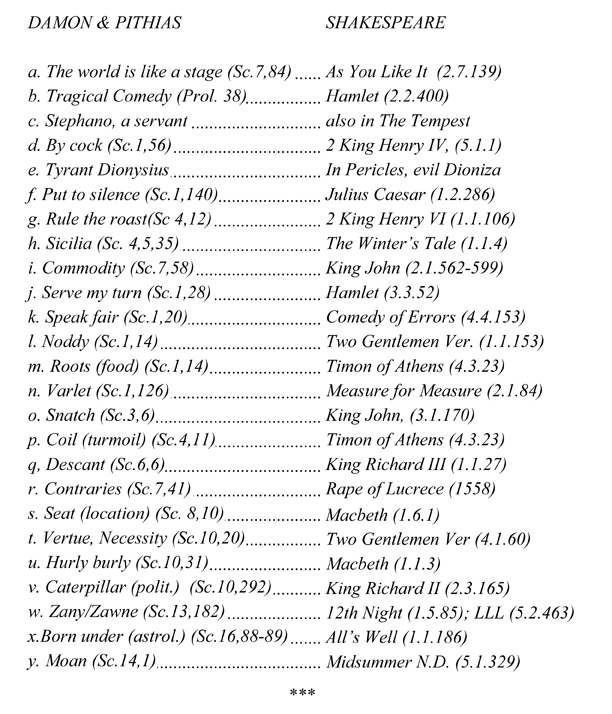

4. Damon and Pithias / Shakespeare: Comparative Lexicon

Of course, this comparative lexicon is only a cross-section. The interested reader can find many other instances equally illuminating. Given the frequency of identical terms and locutions there is ample evidence supporting the proposition that the writer of Damon and Pithias was to become the source of the Shakespeare canon. Particularly impressive is the appearance of a minor character (Stephano) in both D&P and The Tempest. Given the singularity of this name in Tudor drama, its presence in a brace of plays is noteworthy, and, together with the other shared material, is ample proof of our thesis. To reduce such conjunctions from identity to a matter of mere influence would mean that Shakespeare became Shakespeare by reading the vastly inferior author of Damon and Pithias. It would mean that the tragicomical was conceived not by Shakespeare but by a cipher like Richard Edwardes, innocent of all philosophy. Damon and Pithias, whatever else it may be, is a Platonic dialogue, an academic production first performed for a scholarly audience at Cambridge University before a monarch expert in Greek and Latin. As its writer moved away from academe so did his plays become less distinctly reflections of intellect and displays of advanced learning and more treatments of life. The ever-beckoning yeoman Gulielmus Shakesper, born in 1564, never attended an institution where ancient Greek philosophy was an essential part of the curriculum. (See, en passant, Troilus and Cressida.) Newborn infants, whatever else they may be, are not masters of art. There can be no rational claim that it was Gulielmus Shakesper who penned Damon and Pithias, from which it follows that he is absolutely ruled out as the savant who passed from D&P to the Canon. And it is respectfully submitted that there are no other possibilities—except Oxford.

5. The Advent of Genius: The Song of Pithias and its Successors

Near the conclusion of Damon and Pithias there suddenly breaks forth an onrush of lamentation as Pithias reacts to the sentence of doom upon the truant Damon. All levity here runs dry as we behold the sharp turn to the tragic. In putting these events in context it is helpful to return to the Dedication of the play, where, Oxford reminds his Queen: “True friends for their true prince refuseth not their death.” The meaning is plain. Just as anguished Pithias exclaims that he is willing to lay down his life for his friend, so Oxford, the young dramatist and Elizabeth’s “true friend,” is willing to sacrifice himself to preserve and protect her. These ennobling sentiments will later reverberate throughout the works of Shakespeare. We may begin our critical audition with the dirge of Pithias.

Introit

What way shall I first begin my moan?

What words shall I find apt for my complaint?

Damon, my friend, my joy, my life, is in peril, of force I must now faint.

But, O Music, as in joyful times thy merry note did borrow,

So now lend me thy yearnful tunes to utter my sorrow.

Song

Awake, ye woeful wights,

That long have wept in woe:

Resign to me your plaints and tears

My hapless hap to show.

My woe no tongue can tell,

No pen can well descry:

O, what a death is this to hear,

Damon my friend must die!

The loss of worldly wealth

Man’s wisdom may restore,

And physic hath provided too

A salve for every sore.

But my true friend once lost

No art can well supply:

Then what a death is this to hear,

Damon my friend should die!

My mouth refuse the food,

That should my limbs sustain:

Let sorrow sink into my breast

And ransack every vein:

You furies, all at once

On me your torments try:

Why should I live, since that I hear

Damon my friend should die?

Gripe me, you greedy grief,

You sisters three with cruel hands,

With speed now stop my breath,

Shrine me in clay alive,

Some good man stop mine eye:

O Death, come now, seeing I hear

Damon my friend must die!

(Sc. 10, 32-74)

Nothing can prepare us for this moment, which is the very genesis of Shakespeare’s voice. Towering above the rest of the jocund text, the dirge displays inspiration and inwardness of spirit without clash or sentimentality. We behold in 1564 the phenomenon that the late Harold Bloom would dub “the invention of the human.” Little did he realize how early it was conveyed to us, or in what miraculous a manner. For Bloom, the “invention of the human” is initiated by the Bastard in King John (c. 1591), that is, 27 years after the fact. Because Bloom doesn’t notice Damon and Pithias, when he comes to the royal brothers of Cymbeline he fails ironically to “delve [them] to the root,” that is, their poetic roots in Damon. (Cymbeline, 1.1.28) Hear now Arviragus and Guiderius and compare.

Song in Cymbeline

Fear no more the heat o’ th’ sun,

Nor the furious winter’s rages,

Thou thy worldly task hast done.

Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages.

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers come to dust.

Fear no more the frown o’ th’ great,

Thou art past the tyrant’s stroke.

Care no more to clothe and eat,

To thee the reed is as the oak.

The scepter, learning, physic, must

All follow this and come to dust.

Fear no more the lightening flash

Nor th’ all-dreaded thunder-stone.

Fear not slander, censure rash.

Thou hast finished joy and moan.

All lovers young, all lovers must

Consign to thee and come to dust.

No exorcisor harm thee!

Nor no witchcraft charm thee!

Ghost unlaid forbear thee!

Quiet consummation have,

And renowned be thy grave!

(4.2.259-282)

Note the stately elements of tone, pace, and meter which these two lyrics share, how each transforms its surroundings, translating them from the mundane to the exalted, from whose peaks we gaze upon the vales of loss and sorrow. Consider the use of identical and parallel terms, “joy,” “moan,” “physic,” “resign to me,” (D&P), and “consign to thee,” (Cymbeline).” In such likenesses we soar far beyond any reasonable coincidence. As Harold Bloom terms the dirge in Cymbeline “the finest of all songs in Shakespeare’s plays,” (Bloom, 629) we may be sure that, had he considered it, he would have praised the song of Pithias, perhaps more highly, as it was, after all, a piece of Shakespearean juvenilia.

There is yet a third light-hearted play in the Canon which acquires sudden gravitas in this manner: A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Up until the song of Flute (as Thisbe), the audience has been treated to risible foolery in which lovers collide and bumbling mechanicals are proof against sobering losses. Thus, when we finally come to the “tedious and brief scene of Pyramus and his love, Thisbe, very tragical mirth,” (5.1.125-340) there is a tendency to anticipate the heroine’s grieving over the death of young Pyramus as though she were just another clown sent to make us merry. Peter Quince’s actual script, however, strikes a more solemn note.

Thisbe’s Lament

Asleep, my love?

What, dead, my dove?

O Pyramus, arise,

Speak, speak, Quite dumb?

Dead, Dead? A tomb

Must cover thy sweet eyes.

These lily lips,

This cherry nose,

These yellow cowslip cheeks

Are gone, are gone.

Lovers, make moan.

His eyes were green as leeks,

O, sisters three,

Come, come to me

With hands as pale as milk.

Lay them in gore,

Since you have shore

With shears his thread of silk.

Tongue not a word

Come, trusty sword,

Come, blade, my breast imbrue

And farewell friends,

Thus Thisbe ends.

Adieu, adieu adieu.

(5.1.320-342)

Here for the third time we are confronted with “moan.” And “sisters three,” which we heard in the song of Pithias, is also present in the farewell of Thisbe in Midsummer Night’s Dream (and in King Henry the Fourth, Part Two, 2.4.196., and also, Macbeth, 2.1.19) The well-nigh irresistible conclusion is that Oxford’s spirit emerged in the summer of 1564 at Cambridge, and that Damon and Pithias continued to be the lodestone to which he returned repeatedly throughout his career.

Perhaps the most notable instance is found in Romeo and Juliet, 4.4.151-168, in which one of Oxford’s early ballads (“When griping grief the heart doth wound”) is attributed to Edwards. To the foregoing evidence must be added the compendium of Edward de Vere’s published poems which can be found in Roger Stritmatter’s searching paper “Twenty Poems of Edward de Vere Echo in the Work of Shakespeare” published in the newsletter of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Compare with the dirge of Pithias.

Poem 2, line 13: “Thus like a woeful wight I wove my web of woe”

Poem 3, line 13: “Drown me you trickling tears, you wailful wights of woe”

Poem 6, line 13-14 “What worldly wight can hope for heavenly hire,

When only sighs must make his secret moan”

Poem 9, lines 5-8, 13 “In woeful song, in dole display

My pensive heart for to bewray.

Bewray thy grief, thou woeful heart with speed

Resign thy voice to her that caused thy woe”

The stricken deer hath help to heal his wound.”

It is significant that in the same conversation with Horatio in which the Prince refers to “Damon dear,” Hamlet recites as follows:

Why, let the stricken deer go weep,

The hart ungallèd play,

For some must watch, while some must sleep,

So runs the world away.

(3.2.259-262)

Is anyone sufficiently heedless to pass over such matches? These passages weave links amongst: (1) Damon and Pithias, (2) Hamlet, (3) A Midsummer Night’s Dream, (4) Cymbeline and, (5) the undisputed poetry of the young Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. The evidence of Oxford’s hand in all these is fairly overwhelming.

6. Oxford’s Descent

The idea that “Shakespeare” was merely under the influence of an early play by Richard Edwardes is absurd. There is no independent evidence that he was the author. The notion that such a mediocrity might have taught Shakespeare to write could only occur to one unacquainted with his actual works and the text of Damon and Pithias. Is it reasonable to suppose that a mere choirmaster would compose a successful theater piece in 1564, relished by the Queen of England, yet not have it acknowledged during his lifetime? And it is well known that in Tudor England dramatic activity was in ill repute for members of the British nobility and their names could not be affixed to plays for the stage. This was especially true in the case of royalty. It was acceptable for young Oxford to fete the Queen with a theatrical work of his own, but under the protocols of the day it would have had to bear someone else’s name or be featured as “Anonymous.”

Earlier we raised the question of how it was that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford commanded the attentions of the reigning Monarch of the land. If we consider that it was Elizabeth who personally visited him at the Vere estate in 1561, had him transferred to the Court of Wards in London in 1562, and personally included him in the summer progresses of 1564 (Cambridge) and 1566 (Oxford University), her abiding interest in him seems fairly maternal. Could he have been her son, begot in her reckless youth prior to the myth of the “Virgin Queen?” Well, Elizabeth herself was born an illegitimate (Elizabeth’s Glass, Marc Shell, Nebraska, 1993, pp. 16-22); and so would be any son born to her, having no husband. Historian Nigel Cawthorne says of her reputed career of stately chastity:

Despite pressure from her advisors, particularly her chief secretary William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Elizabeth preserved her independence by developing the cult of the Virgin Queen, although it is unlikely that she remained a virgin. Even before she came to the throne there was a rumor that she had been made pregnant by her guardian, the pathologically ambitious Thomas Seymour. He was the last husband of widow Catherine Parr and many of his visits to Elizabeth had been made while his wife was alive. But Catherine died in 1548, which made Thomas’ brother Edward the Lord Protector, even more convinced that he intended to marry Elizabeth. Seymour was arrested and executed in 1549. (Cawthorne, 114)

A child of the Seymour/Elizabeth affair would have been 14 or 15 in 1564, close enough to warrant examination. Cawthorne goes on to identify eight of Elizabeth’s lovers, including Thomas Seymour, who seems to have used force to fulfill his desires. Though Cawthorne omits the likely consequences of Elizabeth’s promiscuity, artfully camouflaged under the rubric of the “Virgin Queen,” everyone knows that Tudor England was rife with noble bastards. If Elizabeth did engage in serial romances, as no serious scholar of the period can anymore gainsay, she would have mothered any number of children. The “Court of Wards” was in fact a nursery and school for her brood, whose vanguard was represented by Edward de Vere. The answer to our question, then, is that the most sensible explanation for the Queen’s special interest in him is that she was indeed his mother. This is alluded to in Shakespeare’s art. Those interested in evidences in the plays of “Shakespeare’s” illegitimacy may commence their research with the Bastard’s parentage in The Life and Death of King John. (2.1.253) Hearken to the poignant confession of Lady Falconridge to her eldest son Philip in the first Act.

King Richard Coeur-de-Lion was thy father.

By long and vehement suit was I seduced

To make room for him in my husband’s bed.

Heaven lay not my transgression to my charge!

Thou art the issue of my dear offence,

Which was so strongly urged past my defence.

(1.1.253-258)

As her eldest child, Edward de Vere had a colorable claim to the Throne of England, a claim finally suppressed by the loving regent who reared him from afar. This awkward position was the built-in irony driving his career as a poet and literary artist. The theatre was his refuge, just as it was for Hamlet. Further, he was given an education for which “superlative” would be an insufficient characterization. Another telling event in 1571 was the passage by Parliament of the “Treason Act,” which made it a capital offense to assert that anyone had a right to the throne following Elizabeth except for the “natural issue” of her body. Use of the locution “natural issue” instead of the conventional “legitimate heirs” strongly implies that Elizabeth had indeed produced bastard children, and that it was her original intention that her first born, the 17th Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere, should inherit the Throne from her. (See, 13 Eliz. C.1) Let it also be mentioned that there is no record that Edward de Vere’s putative mother, Margery Golding (1526-1568) wife of John, the 16th Earl of Oxford, or any other representative of the Vere clan, attended either the commencement ceremonies at Cambridge or Oxford where Edward received degrees. Margery was just 38 when her supposed son received that degree. Had she been indisposed she ought to have sent a relative but history on this key point is mute.

Elizabeth’s very special son Edward did not desert poetry and drama after 1566. On the contrary, he flooded the stages of London with astonishing works still produced and admired today. Surely it was at the behest of the Queen that Damon and Pithias was memorialized in 1571, the same year as the aforementioned Treason Act. Later, having changed her mind about Oxford’s inheritance, Elizabeth sent him by way of consolation in 1575 on a grand and exceedingly expensive tour of the continent, including months in Italy, which provided the sites of comedies and tragedies, including Venice, Verona, Rome, Mantua, and other locations. (The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Richard Roe, Harper, 2011.) In play after play Elizabeth’s image radiates in one heroine after another, as scholar Charles Beauclerk demonstrates so acutely in Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom: The True History of Shakespeare and Elizabeth (Grove Press, 2010). Indeed, careful study will show that it was Elizabeth who was the masked lady of the Sonnets and the two long poems. (The Monument, Hank Whittemore, Meadow Geese Press, 2005.) As for Damon and Pithias, it represents nothing less than the advent of the tragicomical in English theater, inaugurating a fresh genre reflected in such later works as Twelfth Night, Pericles, Love’s Labour’s Lost, The Winter’s Tale, and Measure for Measure. Through rough-hewn Damon and Pithias we behold with fresh understanding and sympathy the marvels to come.

7. The Long Path to Hamlet

In his ultimate Damonic exercise, Hamlet, the dramatist we remember as “Shakespeare” returns to his original theme of friendship. In Act 3, Scene 2, the Prince extols the character of Horatio and lets us see not only his philosophy but his deepest feelings.

Since my dear soul was mistress of her choice

And could of men distinguish, her election

Hath sealed thee for herself; for thou hast been

As one in suff’ring all that suffers nothing,

A man that Fortune’s buffets and rewards

Hath ta’en with equal thanks; and blest are those

Whose blood and judgement are so well commingled

That they are not a pipe for Fortune’s finger

To sound what stop she please. Give me that man

That is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him

In my heart’s core, ay, in my heart of hearts,

As I do thee.”

(3.2.61-72)

Hamlet’s sense of the juncture of two hearts in one descends directly from the outlook of Damon and Pithias, Shakespeare’s opening tale. Just as Pithias is willing to sacrifice himself for the sake of Damon, Prince Hamlet is convinced that he and Horatio are of the same mettle. In this he is shown to be correct. At the ultimate confrontation of enemies in the duel scene of Act 5, in which Hamlet is undone with tainted sword, his principal deed is to kill Claudius (thus refuting the canard that holds him incapable of action) by forcing the lethal drink down the villain’s throat. When Horatio declares he will perish with Hamlet using the same potion, the prince wrests it from his grasp, swallowing the remaining contents and sparing his treasured comrade’s life. Horatio’s intended self-sacrifice is thus answered by Hamlet’s salvific act of self-destruction. In this way the play Hamlet completes and transcends the principle of self-sacrifice announced in Damon and Pithias. For all his courage, Pithias is spared in the earlier play, while Horatio and Hamlet act out the very fatal deed yet shorn of consequences, as Hamlet is already “dead” while Horatio is prevented from finishing what he intended. Oxford’s Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark fulfills the vision of noble friendship first portrayed in Damon and Pithias.

Sources

Books

Mark Anderson, Shakespeare by Another Name, Gotham Books, 2005

Charles Beauclerk, Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom, Grove Press, 2010

Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry, Oxford, 1997

___________, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, Riverhead Books, 1998

Nigel Cawthorne, Kings and Queens of England, Metro Books, 2010

Michael Delahoyde, “Damon and Pithias: Oxford Juvenilia,” Shakespeare Matters 5/1/Fall 2005

John Farmer, ed., The Dramatic Writings of Richard Edwards, Hard Press Publishing, 2014

John Guy, Tudor England, Oxford University Press, 1988

Charlton Ogburn, The Mysterious William Shakespeare, Dodd Meade & Co, 1984

Maria Perry, The Word of a Prince, Boydell Press, 1995

Richard Roe, The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Harper Perennial, 2011

A.L. Rowse, The Elizabethan Renaissance: The Life of Society, Scribner, 1971

Marc Shell, Elizabeth’s Glass, University of Nebraska Press, 1993

Gary Taylor, Stanley Wells, eds., William Shakespeare: The Complete Works, Clarendon Press, 2d Ed., 2005 [All Shakespeare cites to this edition]

Alison Weir, The Life of Elizabeth I, Ballantine, 1998

Hank Whittemore, The Monument, Meadow Geese Press, 2005

Journal

Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Newsletter, 12/19/05

Articles

Janet Clare, “Shakespeare and Early Modern Authorship,” The Journal of Early Modern Studies, University of Florence Press, 2012

Hadley Meares, “Progress of Elizabeth,” History Magazine, 9/9/19

Siblehedingham.com; “Hedingham Castle”

Burghley House, Stamford, Lincolnshire Website

Roger Stritmatter, “Twenty Poems of Edward de Vere Echo in the Works of Shakespeare,” Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Newsletter

Additional Sources

David Paul Gontar, Hamlet Made Simple and Other Essays, New English Review Press, 2013

_______________,Unreading Shakespeare, New English Review Press, 2015

____________________

David Gontar has been writing for New English Review since 2011. Through New English Review Press he has brought out two books on Shakespeare. David is now retired, living abroad and teaching English.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast